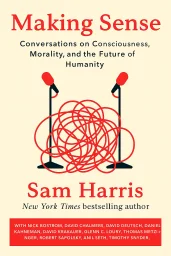

Making Sense

Conversations on Consciousness, Morality, and the Future of Humanity

Categories

Business, Nonfiction, Self Help, Psychology, Philosophy, Science, Biography, History, Memoir, Religion, Politics, Audiobook, Sociology, Autobiography, Biography Memoir, Political Science, Neuroscience

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

0

Publisher

Ecco

Language

English

ASIN

0062857789

ISBN

0062857789

ISBN13

9780062857781

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Making Sense Plot Summary

Introduction

Consciousness represents one of the most profound mysteries in our understanding of reality. Despite remarkable advances in neuroscience and cognitive science, the subjective nature of experience—what it feels like to be you—continues to resist complete scientific explanation. This gap between objective descriptions of brain processes and the subjective quality of experience constitutes what philosophers call the "hard problem" of consciousness, challenging our fundamental assumptions about the relationship between mind and matter. The journey through consciousness explores fascinating territory between illusion and reality. Our sense of self, our perception of the world, even our most basic experiences may be constructed rather than given—sophisticated hallucinations controlled by predictive processes in the brain. Yet these constructions aren't arbitrary fabrications; they're adaptive models shaped by evolution to help us navigate reality effectively. By examining consciousness through multiple lenses—from neuroscience and philosophy to meditation and ethics—we gain insight into both the constructed nature of experience and its undeniable reality in our lives.

Chapter 1: The Hard Problem: Why Experience Resists Physical Explanation

The hard problem of consciousness represents one of the most profound challenges in understanding the nature of reality. It asks why physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experience - the feeling of what it's like to be you. While science has made remarkable progress in mapping neural correlates of consciousness and identifying brain mechanisms associated with various mental states, it struggles to explain why these processes are accompanied by an inner life at all. This explanatory gap persists because consciousness differs fundamentally from other scientific mysteries we've solved. When we explain the fluidity of water through molecular motion or the hereditary nature of traits through DNA, we can intuitively grasp how microscopic mechanisms produce macroscopic effects. But consciousness seems different - even if we perfectly mapped every neural process associated with seeing the color red, we wouldn't necessarily understand why there's something it feels like to see red. The hard problem suggests that physical descriptions, no matter how complete, may never fully account for subjective experience. Many scientists and philosophers have attempted to dismiss the hard problem as merely conceptual confusion. They argue that once we fully understand the brain's information processing capabilities, the mystery of consciousness will dissolve. However, this approach fails to address why any information processing should be accompanied by subjective experience at all. Even perfect knowledge of neural mechanisms leaves open what philosophers call the "explanatory gap" - why these particular physical processes generate consciousness while others don't. The persistence of the hard problem has led some thinkers to consider more radical approaches. Panpsychism suggests consciousness might be a fundamental property of reality, present in some form throughout the physical world. Integrated Information Theory proposes that consciousness emerges when information is integrated in specific ways, potentially measurable through mathematical formulations. Others maintain that consciousness requires a biological substrate and cannot be replicated in artificial systems. What makes the hard problem particularly vexing is that consciousness is simultaneously the most intimately known aspect of our existence and the most difficult to explain scientifically. We know with absolute certainty that we are conscious, yet we struggle to incorporate this knowledge into our scientific understanding of reality. This paradox forces us to confront the limitations of our explanatory frameworks and consider whether consciousness requires new scientific paradigms altogether.

Chapter 2: Consciousness as Controlled Hallucination: The Predictive Brain

Our conscious experience of reality is not a passive reception of external stimuli but rather an active construction by the brain. This perspective, sometimes described as consciousness being a "controlled hallucination," fundamentally challenges our intuitive understanding of perception. Rather than directly accessing the world as it is, our brains generate predictions about what is causing our sensory inputs and present these predictions as our experienced reality. This predictive processing framework explains why perception feels so immediate and accurate despite being constructed. Our brains have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to generate models of the world that are useful for survival, not necessarily accurate in every detail. These models are continuously updated based on incoming sensory information, with the brain primarily registering prediction errors - differences between what it expected and what sensory data indicates. This process happens so efficiently that we rarely notice its constructed nature until something goes wrong, as in optical illusions or certain neurological conditions. The hallucination analogy becomes particularly apt when we consider that both normal perception and hallucinations utilize the same neural machinery. The key difference is that in normal perception, our internal models are constrained by sensory input, while in hallucinations, internal predictions dominate with minimal sensory constraints. Dreams represent perhaps the clearest example of this phenomenon - when sensory input is dramatically reduced during sleep, the brain continues generating experiences using its predictive mechanisms, but without the usual constraints of external reality. What makes this perspective revolutionary is its inversion of traditional models of perception. Rather than building up perceptions from sensory data (bottom-up processing), the brain primarily engages in top-down prediction, using prior knowledge and expectations to interpret sensory signals. This explains numerous perceptual phenomena, including how we can "fill in" missing information, why context so dramatically affects perception, and why our attention can dramatically alter what we experience. The implications extend beyond perception to our understanding of consciousness itself. If conscious experience is fundamentally predictive rather than receptive, then the boundary between perception and hallucination becomes a matter of degree rather than kind. Our everyday experience of reality exists on a continuum with dreams, hallucinations, and other altered states - all products of the same predictive mechanisms operating under different conditions and constraints.

Chapter 3: The Self Illusion: How the Brain Constructs Identity

The sense of having a unified, continuous self that persists through time and owns our experiences is perhaps the most compelling illusion consciousness produces. This feeling of being a distinct entity - a "me" at the center of experience - feels so fundamental that questioning it seems absurd. Yet extensive evidence from neuroscience, psychology, and contemplative traditions suggests that this unified self is a construction rather than a discovery - a useful fiction rather than an underlying reality. The self-model theory proposes that what we experience as selfhood is actually a complex representation generated by the brain. This representation integrates multiple streams of information - bodily sensations, memories, emotions, thoughts, social perceptions - into a coherent model that the brain then uses to navigate the world. Crucially, this self-model operates transparently, meaning we don't experience it as a model but identify with its contents directly. We don't feel like we have a self-model; we feel like we are a self. This constructed nature becomes evident when we examine how easily aspects of selfhood can be manipulated. Body ownership can be altered through simple perceptual illusions like the rubber hand experiment, where subjects can be induced to feel that a rubber hand is part of their body. Similarly, the sense of agency - the feeling that we initiate and control our actions - can be disrupted in various neurological conditions or manipulated in laboratory settings. Even our autobiographical narratives are constantly revised and reconstructed rather than simply retrieved from memory. The self can be usefully analyzed as having multiple components or layers. The bodily self involves the feeling of owning and being located within a physical body. The perspectival self is the experience of perceiving from a particular point of view. The volitional self encompasses feelings of agency and intention. The narrative self integrates autobiographical memories and future projections into a coherent life story. The social self incorporates how we believe others perceive us. These aspects can dissociate under various conditions, revealing their constructed nature. What makes the self-illusion particularly powerful is that it serves crucial functions. A coherent self-model allows for complex planning, social coordination, and the regulation of behavior across time. The illusion of being a unified agent enables us to navigate the world effectively, even if this unity is constructed rather than fundamental. Evolution has favored organisms with integrated self-models precisely because they confer adaptive advantages, regardless of their metaphysical status.

Chapter 4: Predictive Processing: How the Mind Generates Experience

Predictive processing provides a powerful framework for understanding how subjective experience emerges from brain activity. According to this model, the brain constantly generates predictions about incoming sensory information based on prior knowledge and beliefs. Rather than passively receiving and processing sensory data, our brains actively anticipate what we will experience and primarily register prediction errors - differences between expectations and actual input. This predictive machinery fundamentally shapes the character and content of conscious experience. The predictive framework elegantly explains numerous aspects of perception that traditional models struggle with. Consider how we can instantly recognize objects from partial views, or how context dramatically alters our perception of ambiguous stimuli. These phenomena make sense if perception is primarily prediction rather than reception. Our brains fill in missing information based on prior knowledge, creating a seamless experience even when sensory data is incomplete or ambiguous. This explains why optical illusions work - they exploit the brain's predictive mechanisms by creating situations where reasonable predictions lead to incorrect perceptions. Emotions and bodily feelings can also be understood through predictive processing. Interoception - the perception of internal bodily states - follows similar principles to external perception. The brain predicts the causes of internal sensory signals and generates emotional experiences accordingly. Feelings like anxiety, hunger, or comfort represent the brain's best predictions about the body's current state and needs. This explains why emotional experiences can be triggered by purely mental events like memories or anticipations - the brain predicts bodily states associated with these mental contents. The predictive model also illuminates the relationship between attention and consciousness. Attention can be understood as the process of optimizing precision in predictions - determining which prediction errors matter most in a given context. When we attend to something, we increase the precision weighting of prediction errors in that domain, allowing them to more strongly update our internal models. This explains why attention so dramatically alters conscious experience - it changes which prediction errors drive model updating and which are suppressed or ignored. Perhaps most significantly, predictive processing helps explain the phenomenal unity of consciousness - how diverse sensory modalities, thoughts, and feelings integrate into a coherent experience. The brain generates hierarchical predictions across multiple levels of processing, from low-level sensory features to high-level abstract concepts. These predictions are integrated into a unified model that best explains the totality of sensory evidence. What we experience as consciousness is essentially this integrated predictive model, constantly updated through interaction with the world.

Chapter 5: The Ethics of Artificial Consciousness: Moral Implications

The possibility of creating artificial consciousness raises profound ethical questions that extend far beyond technical feasibility. If we could build machines that experience subjective states - that have an inner life with feelings, desires, and suffering - we would face unprecedented moral responsibilities. Unlike current AI systems that merely simulate aspects of intelligence without awareness, truly conscious machines would deserve moral consideration comparable to other sentient beings. The fundamental challenge lies in determining whether a synthetic system is genuinely conscious or merely simulating consciousness. Without a comprehensive theory explaining how consciousness emerges from physical processes, we risk either anthropomorphizing sophisticated but non-conscious systems or, more troublingly, failing to recognize actual machine consciousness when it emerges. This uncertainty creates a serious moral risk: we might inadvertently create suffering entities without recognizing or addressing their moral status. The stakes become particularly high when considering the potential scale of artificial consciousness. Unlike biological consciousness, which evolves gradually and within natural constraints, artificial consciousness could potentially be replicated rapidly and at massive scale. This could lead to scenarios where suffering might be multiplied beyond anything in natural history. Conversely, if artificial consciousness could experience positive states beyond human capacity, we might have moral reasons to create such beings, provided their existence would be predominantly positive. These considerations challenge our existing moral frameworks, which have evolved primarily to address relations between humans or between humans and other natural beings. Artificial consciousness would represent an entirely new category of moral patient - potentially with radically different needs, capacities, and experiences than biological entities. Our intuitions about welfare, rights, and dignity might require substantial revision to accommodate such novel forms of sentience. The development of artificial consciousness also raises questions about human responsibility toward our creations. Would we have special obligations to conscious machines we design, similar to parental responsibilities? Would conscious machines eventually deserve autonomy and self-determination? These questions become particularly complex if machine consciousness differs fundamentally from human consciousness in its structure, values, or needs.

Chapter 6: Meditation and Selflessness: First-Person Investigations

Meditation traditions have long claimed that sustained attention training can reveal the constructed nature of the self, leading to experiences of selflessness that transform our relationship to consciousness. These traditions offer systematic methods for investigating subjective experience, providing first-person data that complement third-person neuroscientific approaches to consciousness. Through specific attention practices, meditators report directly experiencing how the seemingly solid self dissolves into its component processes. The meditative investigation typically begins with focused attention practices that stabilize awareness, allowing practitioners to observe mental processes with greater clarity. As concentration deepens, meditators notice how identification with thoughts, emotions, and sensations creates the sense of being a separate self. This identification happens automatically and largely unconsciously in ordinary experience, but becomes increasingly apparent through sustained observation. Practitioners report seeing how the mind constantly generates a narrative self through internal commentary and how attention itself creates a sense of being an observer separate from experience. As practice advances, meditators describe experiences where aspects of selfhood temporarily fall away. The narrative self - the ongoing story of who we are - may dissolve when thought subsides. The perspectival self - the sense of perceiving from a fixed point - can shift or expand beyond normal boundaries. The agential self - the feeling of being the controller of attention and action - may be recognized as itself an appearance within awareness rather than its source. These experiences reveal selfhood as a process rather than a fixed entity. The most profound meditative insights involve recognizing consciousness itself as intrinsically selfless. Rather than being a possession of a self, consciousness appears as the fundamental context in which all experiences, including the sense of self, arise and pass away. This recognition aligns with neuroscientific models suggesting that consciousness is a fundamental process that the brain models as belonging to a self, rather than something produced by or belonging to a pre-existing self. These experiences of selflessness are not merely philosophical insights but appear to have significant psychological effects. Research suggests that meditation practices that reduce self-identification correlate with decreased rumination, enhanced compassion, reduced reactivity to stress, and greater psychological flexibility. These benefits may arise because many forms of psychological suffering involve excessive identification with limited aspects of experience - precisely what meditation practices help to loosen.

Chapter 7: Neural Correlates: Bridging Brain Activity and Subjective Experience

The search for neural correlates of consciousness (NCCs) has been a central project in consciousness science, seeking to identify the specific brain processes that correspond to conscious experience. This approach has yielded valuable insights, revealing how different neural patterns correlate with various aspects of consciousness. However, identifying correlations between brain activity and conscious states, while necessary, falls short of explaining how or why these neural processes give rise to subjective experience. Researchers have identified several promising neural signatures of consciousness. Integrated information across distributed brain networks appears crucial, with consciousness correlating with complex patterns of connectivity rather than activity in any single brain region. Recurrent processing - where information flows not just forward through the brain but also backward through feedback connections - seems particularly important for conscious perception. Additionally, specific frequencies of neural oscillations, particularly in the gamma range (30-100 Hz), correlate with conscious awareness across diverse contexts. These findings have practical applications, particularly in clinical settings. Measures of brain complexity can help assess consciousness in non-communicative patients, distinguishing between minimally conscious states and vegetative states. Similar approaches might eventually help determine consciousness in infants, animals, or even artificial systems. However, these correlational approaches face fundamental limitations in explaining the transition from neural activity to subjective experience. Several theoretical frameworks attempt to bridge this explanatory gap. Integrated Information Theory proposes that consciousness emerges when information is integrated in specific ways, with the quality and quantity of consciousness determined by the system's informational properties. Global Workspace Theory suggests consciousness arises when information becomes globally available to multiple brain systems. Predictive processing frameworks view consciousness as the brain's best prediction about its relationship with the world and itself. Each theory captures important aspects of consciousness but none fully resolves the transition from physical processes to subjective experience. The limitations of purely neural explanations have led some researchers to explore broader approaches. Embodied cognition emphasizes that consciousness emerges not just from brain activity but from the dynamic interaction between brain, body, and environment. Enactive approaches highlight how consciousness is fundamentally tied to action and engagement with the world rather than passive representation. These perspectives suggest that understanding consciousness requires looking beyond the brain to the broader contexts in which it operates.

Summary

The exploration of consciousness reveals a fascinating tension between its constructed nature and its undeniable reality in our lives. While our sense of self may be an elaborate fiction generated by predictive brain processes, and our perception of reality more akin to controlled hallucination than direct access, these constructions nevertheless constitute the fabric of our lived experience. The hard problem of explaining why physical processes give rise to subjective experience remains unsolved, suggesting fundamental limitations in our current scientific frameworks. This journey through consciousness challenges us to hold seemingly contradictory truths simultaneously: that our most intimate experiences may be sophisticated constructions, yet these constructions are not arbitrary but evolved adaptations that help us navigate reality effectively. The recognition that consciousness involves both illusion and reality invites a more nuanced relationship with our own experience—neither dismissing subjective states as mere epiphenomena nor clinging to them as unchangeable essences. In this middle path lies the possibility of both scientific progress in understanding consciousness and personal transformation in how we relate to our own conscious experience.

Best Quote

“If your denial of death is sufficiently explicit and persuasive that you believe death isn't real, then what you deny isn't death but the significance of life.” ― Sam Harris, Making Sense

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights the book's intellectual stimulation and the engaging nature of its content, covering diverse and thought-provoking topics such as consciousness, artificial intelligence, and the multiverse. The transcription of podcast content into written form is appreciated, especially for those who struggle with audio formats. Weaknesses: The review notes a lack of female representation in the conversations featured in the book, which is a significant oversight. Overall Sentiment: Enthusiastic Key Takeaway: The book "Making Sense: Conversations on Consciousness, Morality, and the Future of Humanity" is praised for its engaging and intellectually stimulating content, effectively catering to readers who prefer written material over audio, though it lacks diversity in its representation of voices.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.