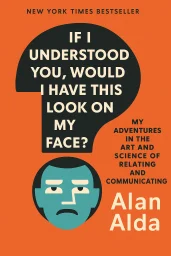

If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look On My Face?

My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating

Categories

Business, Nonfiction, Self Help, Psychology, Science, Biography, Communication, Memoir, Audiobook, Humor

Content Type

Book

Binding

Kindle Edition

Year

2017

Publisher

Random House

Language

English

ASIN

B01M61KNLW

ISBN

0812989163

ISBN13

9780812989168

File Download

PDF | EPUB

If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look On My Face? Plot Summary

Introduction

Imagine sitting across from someone whose words seem like a foreign language, their expressions a puzzle you can't solve. The dentist who mutters about "tethering" before cutting into your mouth. The engineer who speaks in acronyms while you nod politely, understanding nothing. The partner whose feelings remain a mystery despite years together. We've all been there—caught in that frustrating gap between speaking and truly connecting. Communication breakdowns happen everywhere, from boardrooms to bedrooms, and the consequences range from minor misunderstandings to profound isolation. Yet what if the solution isn't about speaking more clearly, but about something deeper—about genuinely seeing the person across from us? This exploration takes us on a journey through the science of human connection, revealing how actors, scientists, and successful communicators bridge the gap between minds. By developing the ability to read others—to sense what they're thinking and feeling—we unlock a powerful tool that transforms every interaction. The path forward isn't about mastering techniques or memorizing rules, but about awakening our natural capacity for empathy and understanding. When we truly tune in to others, communication becomes not just effective, but transformative.

Chapter 1: The Dentist's Scalpel: A Watershed Moment in Communication

The dentist hovered over me, scalpel in hand, poised inches from my face. "There will be some tethering," he announced abruptly. My mind raced. Tethering? What could that possibly mean for my mouth? I wanted to ask more questions, but his impatient demeanor made me hesitate. When I finally mustered the courage to ask what "tethering" meant, his response was to bark the word at me repeatedly, as if volume would clarify meaning. Intimidated by his surgical gown and growing irritation, I acquiesced. "Okay," I said, and he proceeded to cut into my mouth. This brief encounter would change my life in unexpected ways. Weeks later, while filming a movie, the director of photography approached me after a take. "Why were you sneering? I thought you were supposed to smile." Looking in a mirror, I discovered that my smile had transformed into a sneer—my upper lip now drooped lazily over my teeth. The dentist had severed my frenum, the small bit of connective tissue between my gum and upper lip, without properly explaining the procedure or its consequences. When I called him to explain that I made my living with my face and sometimes needed one that could smile, his response was curt: "I told you there were two steps to the procedure. I haven't done the second step yet." Later, he sent a formal, cold letter that seemed designed primarily to discourage a lawsuit rather than express concern for my discomfort. There was no hint of apology for my feeling somewhat mutilated. Yet this experience wasn't entirely negative. My encounter with the dentist came to symbolize something that happens frequently in life—brief moments that threaten relationships by damaging the delicate tissue of connection. Despite his intense gaze, I realized the dentist hadn't actually seen me as a person. I was merely an item on his checklist, someone he was speaking to through the vague mist of interpersonal nothingness. Those minutes in the dentist's chair became my reference point for profoundly poor communication and what causes it: disengagement from the person we hope to understand. This disconnection stands in the way of success and happiness in every domain, from business to personal relationships. Not being truly engaged with others, and then suffering the consequences of misunderstanding, is the grit in the gears of daily life—but it doesn't have to be this way.

Chapter 2: From Stage to Science: The Power of Relating

My journey into the heart of communication began on stage, where I discovered a fundamental truth about human connection. As a young actor, I was constantly told to "relate" to my fellow actors, but I had only a vague understanding of what relating actually meant. I thought it involved physically leaning toward the other person, so when asked to relate more, I would tilt in their general direction like an errant telephone pole. If the director pushed for even more relating, I would hunch over further, positioning my nose closer to the other actor's face. During rehearsals for the Broadway musical "The Apple Tree," director Mike Nichols grew frustrated with my approach. "You kids think relating is the icing on the cake," he said pointedly. "It isn't. It's the cake." This insight took years to fully absorb, but eventually I came to understand: Relating means being so aware of the other person that, even with your back to them, you're observing them. It's letting everything about them affect you—not just their words, but their tone of voice, body language, and even subtle things like where they're standing in the room. Relating is allowing all that to seep into you and influence how you respond. This kind of responsive listening became clearest to me during improvisational theater training. In my early twenties, I performed in a cabaret show where we developed sketches through improvisation and even created new material on the spot based on audience suggestions. But the real breakthrough came when I joined a workshop conducted by Paul Sills, founder of Second City. His mother, Viola Spolin, had created a rigorous form of improvisation training that built actors' ability to connect spontaneously with one another. In these sessions, we played games and exercises that transformed us. What one player did was immediately sensed and responded to by others, creating a dynamic cycle of genuine interaction. After six months, I felt these improv sessions had changed me both as an actor and as a person. I had discovered that true relating happens when we allow ourselves to be affected by others—to be changed by them—and this genuine connection became the foundation of my approach to communication. Years later, while hosting the PBS show "Scientific American Frontiers," I had the opportunity to test these principles with scientists. During my first interview about solar panels, I made three critical mistakes: assuming I knew more than I did, invading personal space by touching equipment, and failing to truly listen. I was so focused on what I wanted to say that I missed the signals the scientist was sending. Over time, I learned to abandon prepared questions and enter conversations with simple curiosity. When I truly related to scientists—engaging with genuine interest and responsive listening—they became more responsive in turn, speaking naturally about their work without jargon or formality. What I discovered through these experiences is that relating isn't just an acting technique—it's the essential foundation of all communication. When we're genuinely present and responsive to others, we create a dynamic relationship that transcends mere information exchange and becomes authentic human connection.

Chapter 3: Mirror Neurons and Empathy: The Science of Connection

I sat across from Marco Iacoboni, a neuroscientist at UCLA, as warm California sun bathed our outdoor table. He was explaining his research on mirror neurons—special brain cells that activate both when we perform an action and when we see someone else perform that same action. "It's all about simulating the intentions of others," Marco explained. "We're imitating internally what other people are planning to do. This is important because we need to predict what other people are planning to do." "Why?" I asked. "Why is that so important?" "Let's take the two of us. We're having a conversation about the brain. And I can see all your body language. I have a lot of information that allows me to predict what you're going to do next. If I'm unable to read you, this conversation would be much more unsettling to me, because I'll never know if you're about to slap me in the face." According to Iacoboni, mirror neurons don't just help us read actions and intentions—they also allow us to experience others' emotions. When we see someone suffering or in pain, these neurons help us read their facial expressions and make us viscerally feel their experience. These moments, he suggests, form "the foundation of empathy," our ability to understand what another person is feeling. Though some scientists now debate whether mirror neurons function exactly as described or even exist in humans as they do in monkeys, the underlying principle remains compelling: our brains contain some mechanism that allows us to resonate with others' experiences. This resonance creates the basis for two crucial communication skills: empathy (understanding what another person is feeling) and Theory of Mind (awareness of what another person is thinking). I discovered the distinction between these two faculties while filming an episode of Scientific American Frontiers. Young children below the age of four and a half don't yet have a fully developed Theory of Mind—they assume everyone knows what they know. In one experiment, children watched a cartoon where a woman put a cookie on a table and left the room. While she was gone, a man entered, moved the cookie to a cupboard, and left. When asked where the woman would look for the cookie upon returning, young children pointed to the cupboard. They couldn't grasp that the woman's knowledge differed from their own. This natural developmental stage shows why mind-reading is so fundamental. Without Theory of Mind, we can't conceive that deception is possible or that others have different information than we do. But once this ability develops, it becomes a tool we rely on throughout life. We wouldn't hand over money to a used-car salesperson without trying to gauge their intentions. Is this person hiding something? What's their agenda? Our understanding of what's happening in another person's mind comes from multiple kinds of listening—facial expressions, tone of voice, body language, and telling words they might drop. This science of connection reveals something profound: communication isn't just about transmitting information—it's about creating a shared mental space where thoughts and feelings can be accurately perceived and understood. When we practice exercises that strengthen empathy and Theory of Mind, we're not just becoming better communicators; we're developing the fundamental human capacity that makes genuine connection possible.

Chapter 4: Observation Games: Training the Mind-Reading Muscle

Two young scientists stand face-to-face in a workshop at Stony Brook University. They look intently into each other's eyes as one begins to move slowly, with the other mirroring their movements exactly—no lag time, a perfect reflection. This "mirror exercise" is their first taste of how improvisation can transform communication. Initially, they struggle. The follower lags behind because the leader moves too quickly. I coach from the side: "It's the leader's responsibility to help the mirror keep up." This simple insight reveals something essential about communication: if I'm explaining something and you don't follow, it's not just your job to catch up—it's my job to slow down. As they practice, their synchrony improves. Then comes a challenging twist: "Now neither of you is leading; find the motion together." This sounds impossible—how can they move in perfect sync without anyone leading? Yet after some practice, they achieve a kind of instantaneous harmony, moving as one despite neither person being in charge. Their surprise and delight are palpable. They're beginning to read each other's bodies, picking up subtle cues that will eventually lead to reading each other's feelings and thoughts. The exercise progresses to verbal mirroring, where partners must speak the exact same words simultaneously. After initial struggles, they begin achieving brief moments of perfect synchrony: "It makes the whole...science...thing look really easy." When participants ask how these simple games relate to real-world communication, I assure them that through trial and error, we've discovered they work. The games develop an ability to absorb cues from others' body language and tone of voice—an essential skill for connecting with any audience. This intuition is supported by research. At Stanford University, Scott Wiltermuth and Chip Heath found that people who walked in step with others showed more trust and cooperation in subsequent activities than those who walked normally. Even simple tapping in sync produced similar results, with participants paying more attention to group welfare and making fewer selfish choices. At the Weizmann Institute in Israel, Uri Alon's team discovered that when experienced improvisers engaged in leaderless mirroring, their synchrony was actually faster and more precise than when one person led and another followed. Other exercises deepen this connection. Participants build imaginary sculptures out of space, toss invisible balls that maintain their size and weight, and even engage in tug-of-war competitions with ropes that don't exist. These activities work because players observe one another closely and accept the dynamics established by the group. In one particularly revealing game, a scientist enters a room and must convey her relationship to another person solely through behavior, not words. Dr. Martha Furie, a professor of pathology, transformed before our eyes, displaying anger and coldness that immediately conveyed a fraught relationship. Later she confessed, "I'm actually not a person who puts myself out there. I can't believe I did that." These observation games prepare players for more complex interactions, teaching them to communicate with their whole expressive selves rather than merely spraying words at an audience. The result is a heightened ability to tune into others—to sense what they're feeling and develop greater awareness of our own emotions. This connection becomes the bedrock of communication, allowing us to engage with others in a way that transcends mere information exchange and creates genuine understanding. Through these playful yet powerful exercises, participants discover that communication isn't about deciding to behave differently—it's about developing a natural attunement to others that makes connection effortless. When our attention is focused on the other person rather than ourselves, we unlock a deeper capacity for relating that transforms every interaction.

Chapter 5: Storytelling as Connection: Engaging Heart and Mind

The little boy's lifeless body lay facedown on the beach, the edge of the Mediterranean Sea gently lapping at his cheek. Three-year-old Aylan Kurdi had drowned when his family's desperate attempt to flee war-torn Syria ended in tragedy. Within hours, a photograph of his tiny form rocketed around the world on the internet. Suddenly, the refugee crisis wasn't about statistics or politics—it had a face, a story that broke hearts globally. The impact was immediate and profound. In Canada, where Aylan's family had relatives ready to sponsor them but had been denied entry due to missing paperwork, phone lines and inboxes flooded with demands for policy changes. In France, President François Hollande announced his support for distributing refugees among European countries, declaring, "Europe is a set of principles and values. It is time to act." In Britain, Prime Minister David Cameron, who had previously rejected refugee quotas, changed his position the day after seeing the photograph. "As a father," he said, "I felt deeply moved by the sight of that young boy on a beach in Turkey. Britain is a moral nation and we will fulfill our moral responsibilities." This power of story to move people isn't just emotional manipulation—it's deeply rooted in how our brains function. Neuroscientist Uri Hasson at Princeton University discovered this through a remarkable experiment. When someone tells a story about a movie they've watched while in an fMRI machine, the same areas of their brain activate as when they originally watched the film. But the astonishing finding was that when others merely listen to the recording of this person telling the story, the same brain areas activate in the listeners' brains—as if they too were watching the movie. "Storytelling is amazing," Hasson explained. "It has the power to make people really aligned and more effective passing information between them." Even babies seem wired to understand narrative. In an experiment at Yale, six-month-old infants watched a simple puppet show where geometric shapes with button eyes enacted a story: a red disc struggled to climb a hill, a yellow triangle pushed it down, and a blue square helped push it up. When given a choice of which character they preferred, almost every baby reached for the helpful blue square. Researcher Karen Wynn explained that for babies to make this judgment, "there has to be a narrative...it doesn't make sense without this narrative." Neuroscientist Mike Gazzaniga has identified a "sense-making function" in the left brain that he calls "the interpreter," which constantly constructs narratives to explain our experiences. "The vast majority of everything we do goes on outside of our consciousness," he explains. "What comes out of that is how we behave or what we say. We have this left-brain monitoring that's constantly trying to make sense out of that." When asked if this interpreter function literally creates stories, he affirmed: "No, no, no, it's a story. It's how we best understand and can retain the meaning of what our actions are in any given moment." This explains why storytelling is so fundamental to effective communication. When we craft stories with clear goals and obstacles, we tap into an ancient pattern that creates tension, engagement, and ultimately connection. The classic Aristotelian structure—a hero pursuing something important who encounters obstacles—activates our natural empathy. We identify with the struggle, we root for resolution, and in the process, we absorb the meaning embedded within the narrative. As one mathematician said of teaching complex concepts: "The logical tale takes out all the blood and all the mystery, and everything is nice and organized and tidy... But I think that's exactly backwards." The human, messy, story-driven approach engages both heart and mind, making information not just comprehensible, but memorable.

Chapter 6: The Dark Side: When Empathy Is Misused

Bernard Hopkins, a boxer still winning fights at forty-nine, didn't triumph by outpunching opponents but by reading their minds. Studying Sun Tzu's Art of War, he learned to defeat others' strategies by anticipating their moves. Watching an opponent's front foot for the slightest lift, he could predict their next action. "Figuring out what the other guy wants to do and not letting him do it is a matter of policy for Hopkins," wrote Carlo Rotella in the New York Times Magazine. Like his mentor Sun Tzu, who wrote, "If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles," Hopkins used awareness of others' minds not to sympathize, but to defeat them. This reveals an uncomfortable truth: empathy and Theory of Mind are not inherently virtuous. Tuning into another person's thoughts and feelings doesn't necessarily lead to compassion or connection. There's a dark side to empathy that can be exploited for manipulation and control. The stereotypical view suggests empathy makes you soft, but the opposite can be true—when you need to be tough or even cruel, empathy becomes a powerful weapon. Bullies instinctively know how to hurt others because they can read vulnerabilities like a virtuoso playing a violin. Even normally empathic people can be moved to deliver unusual punishment with minimal prompting. In Al Bandura's 1975 experiment, college students delivered higher levels of electric shock to people they heard referred to as "animals" compared to those described as "nice." This slight change in language was enough to activate cruelty through dehumanization. More recently, according to a U.S. Senate report, psychologists were paid $81 million to design and implement interrogation programs at Guantanamo Bay. Using theories of "learned helplessness," they advised on techniques to make prisoners feel helpless and out of control. Rather than building connection, they were using their understanding of human psychology to deliberately break people emotionally—reading minds to break and enter them. Even trusted organizations have weaponized empathy. Merck and Company, despite its distinguished research history, once trained salespeople to use empathy techniques to sell Vioxx even as evidence mounted that the drug caused strokes and heart attacks. According to a congressional memo, representatives were taught precise body language—how long to shake physicians' hands (three seconds), how to eat bread at dinner ("one small bite-size piece at a time"), and how to use "verbal and non-verbal cues" to "subconsciously raise his/her level of trust." Mirroring—matching patterns to "enter the customer's world"—was explicitly taught as a trust-building technique, even while the company prohibited representatives from discussing studies showing the drug's dangers. Psychologist Paul Bloom takes a dim view of empathy partly because it doesn't necessarily lead to moral behavior. He points out that we're more moved by individual suffering—the girl trapped in a well—than by faceless multitudes dying of hunger or genocide. For Bloom, "empathy will have to yield to reason if humanity is to have a future." Yet even he acknowledges that "some spark of fellow feeling is needed to convert intelligence into action." This balanced perspective reminds us that empathy is a tool that can be used for good or ill. Like a hammer that can build homes or commit violence, empathy's power depends on how we wield it. The ability to read others' minds and emotions isn't inherently moral, but when used ethically, it creates the foundation for genuine understanding. Rather than overselling empathy as a cure for humanity's ills, we can value it as an essential component of communication—one that helps us bridge the gaps between minds and create the connections that make life meaningful.

Chapter 7: Overcoming Jargon: Making the Complex Accessible

My wife and I were walking through a spring garden, admiring the flowers blooming after winter. As we strolled, she named each blossom—hyacinth, ranunculus, iris—because calling them by name was part of her loving them. After listening to this botanical litany, I couldn't resist pointing to one she'd missed. "Look at that gorgeous hydrofloxia," I declared with mock authority. She wasn't impressed; she knew I was inventing words. Yet for that brief moment, I enjoyed the pleasure of speaking a private language, even if the word didn't exist. There's something seductive about specialized vocabulary—a private code that offers the intoxicating aroma of insider knowledge. This seduction explains the persistence of jargon, but it can create barriers that bury the very things we most want others to understand. Consider the research paper by "Ike Antkare" titled "Developing the Location-Identity Split Using Scalable Modalities." Its impressive-sounding introduction begins: "The implications of atomic communication have been far-reaching and pervasive. The notion that steganographers connect with 'smart' archetypes is continuously considered intuitive." The problem? This paper is complete nonsense, generated by a computer program called SCIgen. French researcher Cyril Labbé created the fictional scientist to see if machine-generated gibberish could gain credibility. It did—Google Scholar ranked "Ike Antkare" as the 21st most cited author, with more citations than Albert Einstein. Not all jargon is meaningless, of course. In many fields, specialized terms serve legitimate purposes. On a movie set, asking for "the gobo on the Century" and "a half apple" efficiently describes lighting equipment and platforms without lengthy explanations. Among colleagues sharing knowledge, one precise term can replace pages of description. There's also the bonding that comes from shared vocabulary—the sense that "we're the ones who talk like this." This isn't harmful unless it excludes people who should be included, like a doctor speaking incomprehensibly to a patient. The most insidious problem with jargon isn't the words themselves but what psychologists call "the curse of knowledge"—the inability to remember what it's like not to know something. This concept originated in a 1989 paper by economists Colin Camerer, George Loewenstein, and Martin Weber, who discovered that having more knowledge than someone else can actually be a disadvantage in negotiations. The problem isn't the knowledge itself but the inability to imagine not having that knowledge. Once we know something, we unconsciously assume others know it too. Elizabeth Newton, a graduate student at Stanford in 1990, demonstrated this through a simple experiment. She divided participants into "tappers" and "listeners." Tappers chose well-known songs like "Happy Birthday" and communicated them by tapping the rhythm on a table. When asked how often listeners would identify the songs, tappers estimated about 50%. In reality, listeners guessed correctly only 2.5% of the time. The tappers couldn't tap without hearing the melody in their heads, which made it nearly impossible to imagine that listeners weren't hearing it too. This explains why experts struggle to communicate clearly. Scientists and doctors hear the full symphony of their knowledge while their audiences hear only disconnected taps. When a scientist describes a complex process in technical language, or when my childhood teacher answered "What's a flame?" with the single word "oxidation," they're assuming knowledge their listeners don't have. The scientist hears the melody; the audience hears only tapping. And they're liable to think it's a completely different song. Overcoming this curse requires a deliberate effort to remember what it's like to be a beginner—to step back from expertise and connect with the listener's actual starting point. Whether explaining science to the public or communicating complex ideas to colleagues, the most effective communicators recognize that specialized language is a tool, not a badge of intelligence. By focusing on clarity and connection rather than complexity, they build bridges between minds that enable genuine understanding to flourish.

Summary

Throughout this exploration of how minds connect, one truth emerges consistently: genuine communication happens not when we focus on what we want to say, but when we tune in to what others are experiencing. From the dentist's chair to the corporate boardroom, from scientific laboratories to intimate relationships, the magic ingredient is always the same—the ability to read and respond to the thoughts and feelings of others. Whether we call it empathy, Theory of Mind, or simply relating, this capacity transforms the way we communicate, replacing monologues with dialogues and confusion with clarity. The path forward isn't about memorizing communication techniques or crafting perfect presentations. It's about training ourselves to be truly present with others—to observe their facial expressions, listen to their tone of voice, and sense their emotional state. When we practice this kind of attentiveness, whether through improvisation exercises or mindful daily interactions, we develop a natural ability to connect that makes communication feel effortless. As one scientist put it, "Pay attention to what you pay attention to." When we direct our attention toward others rather than ourselves, we create the conditions for understanding to flourish. The most profound connections happen not when we speak with perfect eloquence, but when we listen with perfect presence—when we allow ourselves to be changed by what we hear, and in doing so, change how we're heard by others.

Best Quote

“Ignorance was my ally as long as it was backed up by curiosity. Ignorance without curiosity is not so good, but with curiosity it was the clear water through which I could see the coins at the bottom of the fountain.” ― Alan Alda, If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face?: My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights Alan Alda's exceptional writing skills and his ability to communicate complex ideas in an engaging manner. It praises the book's informative nature and its focus on improving communication through empathy, storytelling, and attentive listening. The reviewer appreciates Alda's use of personal anecdotes to illustrate the importance of understanding and cooperation.\nOverall Sentiment: Enthusiastic\nKey Takeaway: The reviewer strongly recommends "If I Understood You" by Alan Alda for its innovative approaches to enhancing communication skills, emphasizing empathy and understanding. The book is seen as both entertaining and educational, with practical applications for personal and professional relationships.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.