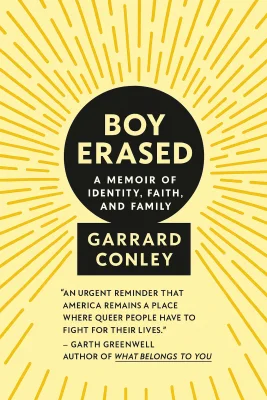

Boy Erased

A Memoir of Identity, Faith, and Family

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, Memoir, Religion, Audiobook, Biography Memoir, Book Club, LGBT, Queer, Gay

Content Type

Book

Binding

Paperback

Year

2017

Publisher

Penguin Publishing Group

Language

English

ASIN

0735213461

ISBN

0735213461

ISBN13

9780735213463

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Boy Erased Plot Summary

Introduction

Garrard Conley was just nineteen years old when his life changed irrevocably. After being outed as gay to his deeply religious Baptist parents, Conley found himself at a crossroads that would test the limits of his faith, identity, and family bonds. As the son of a Baptist minister in small-town Arkansas, his sexuality placed him at odds with everything his community believed. It was 2004, and conversion therapy was still widely practiced across America, promising to "cure" homosexuality through a combination of religious indoctrination, pseudo-psychology, and shame-based techniques. Conley's journey through Love in Action, the oldest and largest ex-gay conversion program in America, offers a rare and intimate glimpse into a world most people never see. Through his eyes, we witness the psychological damage inflicted in the name of salvation, the impossible choice between authentic selfhood and family acceptance, and ultimately, the resilience of the human spirit in the face of extreme pressure to conform. His story raises profound questions about religious freedom, family loyalty, and the search for identity in a world where these forces often collide. As we follow his path from shame to self-acceptance, we gain insight not just into the ex-gay movement, but into the universal struggle to reconcile who we are with who others expect us to be.

Chapter 1: The Shadow of Faith: Early Life and Family Dynamics

Garrard Conley grew up in a world where faith wasn't merely a belief system but the cornerstone of daily existence. Born to deeply religious parents in Arkansas, his father was a car salesman who later answered the call to become a Baptist minister. The Bible wasn't just a book in their household; it was the ultimate authority on all matters of life. Every Sunday morning, Sunday evening, and Wednesday night found the family in church, their lives revolving around the rhythms and teachings of their religious community. From an early age, Conley sensed he was different, though he lacked the vocabulary to articulate exactly how. In the small-town Baptist community where he was raised, homosexuality was not merely condemned – it was rarely even acknowledged as a possibility. When mentioned at all, it was grouped with sins like pedophilia, bestiality, and other "abominations." This created a profound internal conflict for young Conley, who began experiencing same-sex attraction during adolescence but had no framework to understand these feelings except as sinful urges to be suppressed. His relationship with his father was particularly complex. While there was genuine love between them, his father represented the patriarchal authority of both the family and the church. As the son of a minister-to-be, Conley felt tremendous pressure to exemplify Christian virtue. His mother, though equally devout, offered a softer form of faith, one that emphasized love alongside obedience. She became his emotional refuge, the person with whom he could share his doubts, if not his deepest secret. At home and church, Conley absorbed messages about masculinity that left little room for deviation. Sports, manual labor, and heterosexual attraction were presented as the natural path for boys. Anything that strayed from this – from his love of reading to his disinterest in hunting – was viewed with subtle concern. Though his parents never overtly rejected his interests, there was always the unspoken expectation that he would eventually grow into the man God intended him to be: strong, assertive, and destined to lead a Christian family. As a teenager, Conley tried desperately to fit in. He dated a girl from church named Chloe, participated in church activities, and did everything possible to perform the role expected of him. Yet beneath this performance lay a growing anxiety as he realized his attractions weren't changing or disappearing as he'd prayed they would. College initially seemed like an escape, a chance to explore ideas beyond the confines of his religious upbringing. But even there, his deeply ingrained beliefs followed him, creating a constant internal dialogue between the faith he'd been raised in and the identity he was beginning to acknowledge.

Chapter 2: The Unraveling: Discovery and Confrontation

The fragile balance Conley had maintained between his secret identity and his religious life shattered during his first year of college. While attending a small liberal arts school in Arkansas, he formed a friendship with a young man named David. What began as a seemingly innocent connection took a dark turn when David sexually assaulted Conley, then, driven by his own guilt and confusion, called Conley's mother to out him as gay. This devastating betrayal set in motion a chain of events that would alter the course of his life. When confronted by his parents, Conley initially denied the accusation, but the weight of years of secrecy became too much to bear. In a moment of raw vulnerability, he admitted his same-sex attractions to his mother, who reacted with physical illness, rushing to the bathroom to vomit. His father's response was even more pointed: "You'll never step foot in this house again if you act on your feelings. You'll never finish your education." In their worldview, homosexuality wasn't merely a sin; it was a dangerous condition that required immediate intervention. The confrontation created an impossible choice for Conley: maintain his authentic identity and lose his family, or attempt to change his sexuality to preserve the relationships central to his life. Deeply embedded in a culture where family bonds and religious identity were paramount, the thought of being cast out was terrifying. Moreover, at nineteen, he was financially dependent on his parents for his education. The practical realities of his situation left him with little leverage to assert his autonomy. Adding to his anguish was the religious framework through which he still viewed himself. Despite his exposure to more progressive ideas at college, years of religious teaching had convinced him that homosexuality was incompatible with his faith. He feared not just earthly rejection but eternal damnation. In moments of despair, he contemplated suicide, seeing it as a possible escape from the seemingly irreconcilable conflict between his sexuality and his beliefs. After consulting with their pastor, Conley's parents presented him with what they believed was the solution: Love in Action (LIA), an ex-gay conversion therapy program in Memphis, Tennessee. Though skeptical, Conley agreed to attend the program's intensive two-week evaluation called "The Source," after which a determination would be made about whether he needed the full residential treatment. In his vulnerable state, desperate to maintain his family connections and uncertain about his own identity, the program seemed to offer a path forward – however painful it might be. In the weeks leading up to his enrollment at LIA, Conley's life became a study in contrasts. At college, he explored literature that opened new worlds of thought, forming friendships with people who accepted him without judgment. At home, he underwent preliminary therapy sessions that attributed his sexuality to childhood trauma and family dysfunction. Torn between these worlds, he clung to the hope that somehow the program might reconcile the irreconcilable – that he might emerge from it both authentic and accepted.

Chapter 3: Love in Action: Inside Ex-Gay Therapy

On June 7, 2004, Conley entered the Love in Action facility, a nondescript building in suburban Memphis. The imposing figure of John Smid, LIA's executive director, greeted participants with a carefully cultivated image of successful conversion – an ex-gay man who had supposedly overcome his homosexual "addiction" through faith and discipline. The program operated on the premise that homosexuality was not an innate orientation but a sinful behavior pattern stemming from childhood trauma, poor parenting, and spiritual deficiency. The rules at LIA were strict and all-encompassing. Participants surrendered their phones and personal journals. Their wardrobes were scrutinized for "False Images" (FIs) – anything deemed gender-inappropriate. For men, this meant no tight clothing, colorful accessories, or "effeminate" mannerisms. Women were required to wear skirts, apply makeup, and present a traditionally feminine appearance. Even their speech patterns were monitored for "campy" or "gay/lesbian behavior and talk." The facility itself was spartan, with white walls and minimal decoration – a physical manifestation of the stripped-down life participants were expected to embrace. Each day followed a rigid schedule of group therapy, Bible study, and what LIA called "Moral Inventory" (MI) sessions. In these sessions, participants were required to confess their sexual "sins" in excruciating detail, only to have these experiences reframed as evidence of their brokenness. They created "genograms" – family trees marked with codes for various sins like alcoholism, promiscuity, and homosexuality – designed to trace the origins of their "sexual deviance" through generations. The underlying message was clear: their sexuality was not an identity but a pathology with identifiable causes and a potential cure. The psychological tactics employed at LIA were particularly insidious. Participants were taught to distrust their own perceptions and emotions, to see their attractions not as natural feelings but as "the manipulative attacks of Satan." They were isolated from supportive outside influences and surrounded by people who reinforced the program's teachings. The combination of sleep deprivation, constant self-examination, and religious pressure created a perfect environment for indoctrination. Many participants, desperate for acceptance and convinced of their own sinfulness, began to internalize the program's teachings. Conley witnessed the devastating effects of this approach on his fellow participants. Some, like a man he refers to as "T," attempted suicide multiple times during their stay. Others became zealous converts to the program's ideology, policing themselves and others with increasing severity. The atmosphere fostered both desperation and competition – who could demonstrate the most dramatic transformation, who could most convincingly perform heterosexuality. Behind their "ex-gay smiles," however, Conley observed profound suffering and self-alienation. As the days passed, Conley found himself increasingly resistant to the program's techniques, though he tried to participate sincerely. He formed a cautious friendship with another participant called "J," whose intelligence and complexity defied the program's simplistic narratives. These human connections, along with his lifelong love of literature and language, became quiet forms of resistance against LIA's attempts to erase his identity. Even as he went through the motions of therapy, some essential part of him remained intact, questioning and observing the contradictions around him.

Chapter 4: Breaking Point: Crisis and Escape

By the second week at Love in Action, the psychological toll of the program was becoming unbearable for Conley. Sleep deprivation, constant self-monitoring, and the emotional exhaustion of daily "Moral Inventory" sessions left him increasingly disoriented. The program's techniques were designed to break down identity and rebuild it according to their template, but for Conley, this process was creating a dangerous disconnection from himself. He described feeling like "Nothing" – a hollow shell performing the required motions while his authentic self receded further away. The crisis came during a particularly intense group exercise called the "Lie Chair." Participants were required to sit in a chair facing an empty seat that supposedly contained their father, and verbally confront him for the "damage" he had caused. When Conley's turn came, he found himself unable to participate. "I'm not angry," he insisted, despite pressure from counselors who claimed his resistance proved his denial. The blond-haired staff member grew increasingly hostile, accusing Conley of not truly wanting to change. The moment crystallized everything wrong with the program – its insistence on a single narrative of homosexuality, its dismissal of complex family relationships, its demand for performance over authentic healing. In that moment of confrontation, something shifted in Conley. "You're crazy," he told the staff. "You're all completely crazy." He walked out of the session and demanded his phone from the receptionist, who reluctantly returned it. With shaking hands, he called his mother: "Mom, I need your help." It was a pivotal moment – the first time he had directly asked to leave the program, the first clear assertion that what was happening at LIA was harmful rather than healing. His mother, who had been staying at a nearby hotel during his treatment, arrived quickly. The program counselors, particularly Danny Cosby, attempted to convince her that Conley needed to stay, that his resistance was proof he required more intensive treatment – "at least three more months." But something had changed in her as well. Seeing her son's distress and witnessing firsthand the program's methods had raised doubts about whether LIA was truly helping him. "Did you know that man's only college degree is in marriage counseling?" she later remarked. "Why is a marriage counselor telling my son how to be straight?" As they drove away from the facility, the full emotional impact of the experience began to surface. Conley curled against the passenger window, overcome with a mixture of relief, grief, and terror about what would come next. His mother, alarmed by his state, pulled the car to the side of the highway. "Oh my God," she said, "Are you going to kill yourself?" The raw question cut through pretense, bringing the true stakes of conversion therapy into sharp focus. It wasn't merely about changing behavior – for many participants, it was literally a matter of life and death. His mother's question became the turning point in their journey together. "We're stopping all of this now," she declared, taking his distress as confirmation that the program was causing harm rather than healing. Though they had yet to tell his father, though the larger questions about faith and family remained unresolved, this decision marked a crucial break from the ex-gay narrative. For the first time since his outing, Conley's well-being was taking precedence over the promise of a "cure."

Chapter 5: Reclaiming Identity: Life After Conversion Therapy

The immediate aftermath of leaving Love in Action was marked by confusion and disorientation. Conley returned to college physically depleted and emotionally scarred, carrying with him the contradictory messages of the program. Though he had rejected LIA's methods, he hadn't yet developed an alternative framework for understanding his sexuality. The theological constructs that had defined his worldview – sin, salvation, eternal judgment – still exerted powerful influence over his thoughts. He described this period as living with "one foot in a world they'd never seen," caught between his religious upbringing and his emerging identity. The most profound casualty of his ex-gay experience was his relationship with God. Prior to LIA, despite his struggles with his sexuality, Conley had maintained a genuine spiritual life. His faith had been a source of comfort and meaning. Now, he found himself unable to pray, unable to connect with the divine presence that had once been so central to his existence. "What happened to me has made it impossible to speak with God," he explained, "to believe in a version of Him that isn't charged with self-loathing." This spiritual loss created a void that would take years to address, a grief that persisted even as other wounds began to heal. His relationship with his father became particularly strained. Though his father never explicitly rejected him, their interactions grew increasingly awkward and limited. The natural ease they had once shared gave way to stilted conversations and careful avoidance of certain topics. His father continued to fund his education, a silent acknowledgment that perhaps ex-gay therapy had not been the answer, but the emotional distance between them widened. His mother, meanwhile, became his primary advocate and ally, her own understanding evolving as she witnessed her son's struggle to reclaim himself. Academically, Conley threw himself into literature and writing, finding in books the language to process his experiences. Authors like Flannery O'Connor, James Baldwin, and Virginia Woolf offered new ways of thinking about identity, morality, and belonging. Writing became both therapy and vocation – a means of reassembling a self that had been deliberately fragmented. In graduate school, he began crafting the narrative that would eventually become his memoir, though the process was painful and frequently interrupted by self-doubt. Romantically and socially, the path was equally challenging. The program had taught him to associate his sexuality with shame and pathology, creating barriers to forming healthy relationships. "Eleven years later, I still sometimes get nauseous when touching another man," he later observed. "It is difficult (possibly impossible?) to maintain a long-term sexual relationship." Building a community where he could feel both authentic and accepted took time and conscious effort. Gradually, he connected with other ex-gay survivors, finding in their shared experiences validation that had been denied at LIA. Professional success offered another avenue for reclaiming agency. Conley became an English teacher and writer, eventually moving to Bulgaria to teach at an international school. The geographical distance from his Southern Baptist roots provided space to develop his identity away from the cultural pressures that had once constrained him. Through his writing and teaching, he began transforming his painful experiences into something that might help others navigate similar terrain. The boy who had once been told his sexuality was a shameful aberration was now a man using his voice to challenge such harmful narratives.

Chapter 6: Reconciliation: Family, Faith, and Forgiveness

The path toward reconciliation – with family, with faith, with himself – proved neither straightforward nor complete. Years after leaving Love in Action, Conley continued to navigate the aftereffects of his experience. Holidays and family gatherings remained fraught with unspoken tensions. His sexuality, though no longer actively disputed, existed as a kind of ghost in family conversations, acknowledged but rarely directly addressed. When he learned that a deacon had protested his father's invitation to preach at a revival because of his "openly homosexual" son, he confronted once again how deeply intertwined their lives remained. With his mother, the journey toward understanding took a more explicit form. She became an unlikely ally, moving from initial horror at his sexuality to a fierce defender of her son. In recorded conversations that would help form the basis of his memoir, they revisited painful memories together, piecing together what had happened and why. "It'll be over soon," she had once told him on the way to a doctor who was supposed to test his testosterone levels. Years later, she recognized there was no quick fix, no way to make the pain "be over soon." Instead, she committed herself to a different kind of healing – one based on acceptance rather than change. His relationship with his father evolved more slowly and with less direct communication. The pastoral calling that had once seemed to necessitate rejection of his son's sexuality became, paradoxically, a site of possible reconciliation. When Conley called to tell his father he was writing a memoir about his ex-gay experience – a book that might jeopardize his ministry – his father responded simply: "I just want you to be happy. I really do." In this understated declaration, Conley recognized a profound shift, even if full understanding remained elusive. Faith itself underwent a transformation in Conley's life. The certainties of his childhood religion gave way to a more complex spiritual landscape. While the direct connection to God he had once experienced remained difficult to access, he continued to "experiment with different denominations, different religions." The search itself became a form of spirituality – less concerned with doctrinal correctness than with authentic meaning. The boy who had once feared hellfire for his attractions was now a man who could see the divine in human connection and creative expression. Perhaps the most challenging reconciliation was with himself. The ex-gay program had taught him to see his sexuality as something foreign to his true identity, a "False Image" to be excised. Unlearning this bifurcation of self required conscious effort. Writing became central to this process, allowing him to integrate the disparate parts of his experience into a coherent narrative. By naming what had happened to him, by refusing to remain silent about practices that continued to harm LGBTQ youth, he transformed his suffering into advocacy. Through connecting with other survivors of conversion therapy, Conley discovered a community where his experiences were understood without explanation. Organizations like Beyond Ex-Gay provided spaces where former patients could share their stories and support one another's healing. As the ex-gay movement itself began to unravel – with Exodus International disbanding in 2013 and former leaders like John Smid publicly apologizing for the harm they had caused – these survivor communities gained visibility and influence. The personal reconciliation Conley sought became part of a larger social movement toward accountability and change.

Summary

Garrard Conley's journey through ex-gay therapy reveals how institutions designed to "fix" LGBTQ individuals often inflict profound psychological damage in the name of healing. His story illuminates the impossible choices faced by many queer people from religious backgrounds: authenticity at the cost of family and faith, or conformity at the cost of selfhood. Through his experience, we witness both the devastating impact of religious fundamentalism when applied to human sexuality and the remarkable resilience of the human spirit in the face of such pressure. The most powerful lesson from Conley's narrative is that true healing comes not from attempting to change one's fundamental identity, but from integrating it into a whole and authentic self. His journey reminds us that reconciliation – whether with family, faith, or oneself – is rarely complete or perfect, but rather an ongoing process requiring courage and compassion. For those struggling with religious trauma or family rejection, his story offers a path forward that honors both the pain of the past and the possibility of a different future. In the end, Conley's experience stands as both a warning about the dangers of conversion therapy and a testament to the liberating power of telling one's truth, however difficult it may be to speak.

Best Quote

“Love, over time, could either blossom or wither, become a source of wonder or a remembered ache.” ― Garrard Conley, Boy Erased

Review Summary

Strengths: The review notes that the film adaptation of the book has a sharper dramatic arc, a better sense of momentum, and a more satisfying ending compared to the book. The film also benefits from a strong cast, including Lucas Hedges, Russell Crowe, and Nicole Kidman.\nWeaknesses: The book is described as earnest, sombre, and often overwritten with a confusing structure. It lacks a clear depiction of the protagonist's early experiences with same-sex attraction, which is considered essential for such a narrative. The prose is criticized for being overly poetic and tangential.\nOverall Sentiment: Critical\nKey Takeaway: The reviewer finds the book to be a disappointment, particularly when compared to its film adaptation, which is praised for its narrative clarity and emotional impact. The book's structural and stylistic issues detract from its effectiveness in conveying the author's experiences.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.