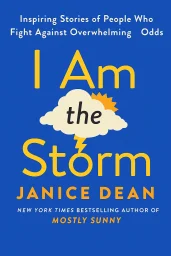

I Am the Storm

Inspiring Stories of People Who Fight Against Overwhelming Odds

Categories

Nonfiction, Memoir, Inspirational

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2023

Publisher

Harper

Language

English

ASIN

0063243083

ISBN

0063243083

ISBN13

9780063243088

File Download

PDF | EPUB

I Am the Storm Plot Summary

Introduction

Courage manifests in the face of overwhelming odds, when ordinary individuals choose to stand against established power structures despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles. This fundamental human capacity—to face giants with nothing more than conviction and determination—represents one of our most profound expressions of moral agency. The decision to challenge authority, whether institutional, political, or cultural, often comes with significant personal risk, yet throughout history, these moments have frequently catalyzed meaningful social change and personal transformation. The courage to confront power emerges from diverse wellsprings: moral clarity that makes silence impossible, personal experiences that reveal systemic injustice, or simply the realization that if one doesn't speak, no one else might. What unites these varied expressions is the psychological journey of finding one's voice amid pressure to remain silent. By examining both historical examples and contemporary cases, we gain insight into the cognitive processes, emotional resilience, and strategic thinking that enable individuals to maintain their resolve when facing institutions designed to withstand and neutralize challenge. Understanding these dynamics offers valuable lessons not only for would-be activists but for anyone navigating ethical dilemmas within asymmetrical power relationships.

Chapter 1: The Psychology of Courage: What Drives Ordinary People to Act

The psychology of moral courage—that distinctive capacity to take principled action despite personal risk—remains one of humanity's most fascinating and consequential attributes. Contrary to popular perception, courage isn't simply an innate personality trait that some possess and others lack. Research increasingly demonstrates that moral courage emerges from a complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, and social factors that can be developed and strengthened over time. At its foundation, moral courage requires psychological clarity—the ability to recognize when a situation demands ethical response despite pressure to remain passive. This recognition often begins with moral attentiveness, a heightened sensitivity to the ethical dimensions of a situation that others might overlook or rationalize away. Studies in moral psychology reveal that individuals who demonstrate courage frequently possess what researchers call "moral identity centrality"—a self-concept where ethical values form a core part of how they define themselves. When such individuals encounter situations that violate these central values, inaction becomes psychologically more costly than action, even when action carries significant risk. The progression from moral recognition to courageous action involves overcoming powerful psychological barriers. Fear represents the most obvious obstacle—not just fear of physical harm, but of social rejection, career damage, and identity threat. Courage emerges not from fearlessness but from the capacity to act despite fear, a distinction that neuroscience now supports by demonstrating that courageous individuals experience the same physiological fear responses as others but show enhanced regulatory capabilities in brain regions associated with emotional control. This explains why practicing small acts of courage can build capacity for larger ones—each experience strengthens neural pathways that facilitate regulation of fear responses. Social psychology adds another crucial dimension to understanding courage—the power of witness. When people observe courageous behavior in others, particularly those within their reference group, they become more likely to act courageously themselves. This "contagion effect" explains why courage often emerges in clusters rather than in isolation, with initial acts inspiring others to follow. The phenomenon partially explains why authoritarian systems work so hard to isolate and discredit dissenters—they intuitively understand that a single visible example of moral courage can catalyze widespread resistance. Perhaps most importantly, research suggests that courage depends less on personality than on specific psychological resources that can be cultivated: clarity of values that provides motivation to act; emotional regulation skills that manage fear; perspective-taking abilities that connect personal actions to broader principles; and social support networks that validate one's moral stance. These findings suggest that courage, rather than being an exceptional quality, represents a capacity that lies dormant in most people, awaiting development through intentional practice and supportive communities. The most striking insight from contemporary research is that courage rarely manifests as a single heroic moment but rather unfolds as a series of small decisions that gradually commit an individual to a course of action. This incremental nature of courage explains why many who later become celebrated for their bravery often report that they never set out to be heroes—they simply responded to immediate ethical demands, one decision at a time, until turning back became impossible. This "action pathway" perspective offers hope by suggesting that courage emerges not from extraordinary character but from ordinary people making consecutive choices aligned with their deepest values.

Chapter 2: Speaking Truth to Power: Moral Clarity in Uncertain Times

Speaking truth to power requires navigating the murky waters where personal conviction intersects with established authority. This process demands moral clarity—an internal compass that remains steadfast despite the disorienting influence of institutional pressure, social conformity, and personal risk. However, this clarity rarely emerges fully formed; it typically develops through progressive stages of ethical awareness as individuals confront situations where established narratives clash with observed realities. The first challenge in speaking truth to power involves overcoming the powerful psychological tendency toward epistemic deference—our natural inclination to trust the judgment of authorities and institutions over our own perceptions. This deference serves valuable social functions in stable contexts but becomes problematic when institutions abuse this trust. The initial spark of moral clarity often appears as cognitive dissonance—an uncomfortable tension between what authorities claim and what one directly experiences or observes. This dissonance creates an inflection point where individuals must either reinterpret their experience to align with authority or begin questioning the authority itself. Those who choose the latter path often describe a moment of clarity where they suddenly perceive institutional narratives as constructed rather than inevitable. Once this initial perception takes hold, individuals face the challenge of articulating a counter-narrative that explains their observations more accurately than the official account. This requires intellectual courage—the willingness to trust one's reasoning despite lacking institutional validation. The process typically involves seeking out alternative information sources, connecting with others who share similar perceptions, and gradually constructing an explanatory framework that makes sense of observed discrepancies. Historical analysis reveals that those who successfully speak truth to power rarely act from pure intuition; they typically build carefully reasoned arguments grounded in evidence, ethical principles, and logical consistency. The transition from private understanding to public truth-telling represents perhaps the most psychologically demanding aspect of the journey. This moment requires confronting deep-seated fears of social rejection, professional retaliation, and identity destabilization. Studies of whistleblowers and dissidents consistently show that successful truth-tellers develop specific psychological strategies to manage these fears: they connect their actions to deeply held values that transcend immediate consequences; they mentally prepare for various negative outcomes; they identify supportive communities that can validate their perceptions; and they frame their actions as service to broader principles rather than personal rebellion. Interestingly, moral clarity often strengthens rather than diminishes when faced with opposition. The psychological mechanism of "value affirmation under threat" explains why many truth-tellers report greater certainty about their position after facing resistance. When core values are challenged, individuals tend to reflect more deeply on these values, reinforcing their commitment. This phenomenon explains why attempts to silence dissent through intimidation often backfire, producing more committed opposition rather than compliance. Perhaps the most profound aspect of speaking truth to power is its transformative effect on identity. Those who undertake this journey frequently describe a fundamental shift in self-understanding—from seeing themselves as participants within a system to recognizing their agency in challenging and potentially changing that system. This transformation represents both the greatest reward and the greatest risk of moral clarity: it offers authentic alignment between values and action but permanently alters one's relationship with previously trusted institutions and authorities.

Chapter 3: Building Resilience: How to Withstand Institutional Pressure

Institutional pressure operates through sophisticated mechanisms designed to maintain conformity and discourage challenge. Understanding these mechanisms represents the first step in developing resilience against them. Most institutional pressure begins subtly—through what sociologists call "soft power"—the use of incentives, social approval, and career advancement to encourage compliance. These positive reinforcements establish psychological patterns that make later resistance more difficult, as individuals become invested in institutional approval. When soft power proves insufficient, institutions typically escalate to more direct forms of pressure: isolation of dissenters, questioning of competence or loyalty, procedural harassment, and ultimately explicit threats to one's position or reputation. The psychological impact of institutional pressure manifests in predictable patterns. Initially, most experience doubt—questioning their own perceptions rather than institutional narratives. This doubt often transitions to anxiety as the personal stakes become clearer, followed by isolation as colleagues distance themselves to avoid association with perceived troublemakers. Without effective countermeasures, this progression frequently culminates in withdrawal—either physical departure from the institution or psychological capitulation to its demands. Research on organizational psychology demonstrates that these responses are not signs of individual weakness but predictable reactions to deliberately designed pressure systems. Building resilience against institutional pressure requires developing specific psychological resources. The first is cognitive reframing—the ability to interpret pressure not as evidence of personal failure but as confirmation that one's concerns have institutional significance. Those who successfully withstand pressure consistently report this perspective shift: they view institutional resistance not as disconfirmation of their position but as validation of its importance. This cognitive reframing converts a potentially demoralizing experience into evidence supporting continued resistance. Another crucial element of resilience involves identity anchoring—establishing self-worth and meaning beyond institutional validation. Those who maintain their stance amid pressure typically draw strength from multiple identity sources: professional ethics that transcend specific institutional contexts, social connections outside the pressuring organization, personal values with deep biographical roots, or spiritual/philosophical frameworks that provide meaning beyond immediate circumstances. This identity diversification prevents institutions from monopolizing an individual's sense of worth and belonging. Strategic documentation serves both practical and psychological functions in building resilience. The practice of systematically recording problematic events, preserving evidence, and maintaining chronologies serves the obvious practical purpose of creating accountability. Less obviously, documentation provides psychological protection against gaslighting—institutional attempts to make individuals question their own perceptions and memories. By creating contemporaneous records, individuals establish reality anchors that help maintain confidence in their observations despite contradictory institutional narratives. Perhaps the most powerful resilience factor is community connection—finding others who share similar concerns or experiences. Isolation powerfully undermines resistance because humans fundamentally need validation of their perceptions. Even minimal connection with others who recognize the legitimacy of one's concerns can sustain resistance through difficult periods. The most effective resisters typically build multiple support networks: professional peers who understand the specific institutional context, family members who provide emotional stability, and when possible, formal advocacy organizations that offer both practical assistance and the knowledge that one's experience reflects systemic rather than personal issues. Research on psychological resilience suggests that successfully withstanding institutional pressure rarely depends on heroic individual qualities but rather on developing specific skills and resources that can be intentionally cultivated. This understanding transforms resistance from a personality trait to a learnable practice, making it accessible to ordinary people facing extraordinary pressures. The most resilient individuals approach institutional challenges not as tests of personal courage but as strategic problems requiring careful preparation, support mobilization, and psychological self-management.

Chapter 4: Finding Your Voice: Effective Communication Strategies

Finding an authentic voice amid institutional pressure requires navigating complex rhetorical terrain. The most effective challengers to power understand that communication involves not just what is said but how, when, and to whom it is said. Developing this strategic communication capacity begins with message framing—articulating concerns in language that resonates with the values and priorities of intended audiences rather than merely expressing personal outrage or frustration. Research on persuasive communication reveals that effective challengers typically connect their specific concerns to broader principles that their audience already endorses. This "values bridging" approach minimizes defensive reactions by demonstrating how addressing the concern actually fulfills rather than violates shared values. For example, military whistleblowers often frame their disclosures not as attacks on the institution but as defense of its core mission and honor, invoking loyalty to higher principles rather than betrayal of immediate authorities. Similarly, corporate whistleblowers frequently frame their actions as protecting the company's long-term reputation and viability rather than attacking its current practices. Timing represents another crucial element of effective communication. Those who successfully challenge power demonstrate tactical patience—understanding when an audience is most receptive to difficult messages. This might mean waiting for external events that validate concerns, identifying moments when institutional legitimacy is already questioned for other reasons, or recognizing when leadership transitions create openings for policy reconsideration. The most effective communicators monitor the social and institutional environment for these strategic openings rather than speaking whenever emotional urgency is highest. Channel selection—choosing the appropriate forum and medium for communication—significantly impacts message effectiveness. Internal channels typically offer lower personal risk but may limit impact; external channels potentially reach broader audiences but increase vulnerability to retaliation. Successful challengers often employ progressive escalation—beginning with internal channels to establish good faith and documentation, then gradually moving to more public forums as necessary. This approach maintains moral and often legal protection while demonstrating reasonable effort to work within established systems before transcending them. Perhaps the most underappreciated aspect of effective communication involves anticipatory framing—preparing for predictable attempts to discredit both message and messenger. Those who effectively challenge power anticipate standard institutional responses: questioning of motives, attacks on credibility, isolation tactics, and issue reframing. By proactively addressing these responses in initial communications, effective challengers can neutralize standard delegitimization strategies. This preparation often includes transparently discussing potential conflicts of interest, acknowledging limitations in one's knowledge, connecting with others who share similar concerns, and explicitly addressing how the issue might be mischaracterized. Emotional regulation significantly impacts communication effectiveness when challenging power. While authentic emotion lends credibility and urgency to communication, unregulated emotion can undermine persuasiveness by triggering audience defensiveness or confirming stereotypes about "emotional" challengers. Research on effective advocacy suggests that controlled passion—emotion clearly present but visibly managed—maximizes persuasive impact. This balanced approach signals both genuine commitment and rational assessment, combining emotional authenticity with strategic self-presentation. The most sophisticated communicators understand that finding one's voice is not a single event but an evolving process that adapts to changing circumstances and audience responses. They continuously refine their message based on feedback, adjust communication channels as needed, and maintain flexibility about tactical details while remaining committed to core principles. This adaptability prevents institutional opponents from defining and containing challenges through predictable response patterns, allowing individual voices to maintain effectiveness even as resistance intensifies.

Chapter 5: The Personal Cost: Balancing Advocacy and Self-Care

Challenging entrenched power structures inevitably exacts personal costs that extend beyond obvious professional risks. The psychological impact of sustained advocacy includes distinct patterns that affect nearly all who undertake this path. Understanding these patterns helps explain why many promising challenges falter over time and provides guidance for maintaining effectiveness while protecting personal wellbeing. Advocacy typically begins with a period of heightened energy and clarity as individuals experience what psychologists call "moral engagement"—the alignment of actions with deeply held values that produces psychological coherence and purpose. This initial phase often brings unexpected benefits: increased meaning, authentic connections with like-minded others, and liberation from the cognitive dissonance of complicity with problematic systems. However, this energizing period generally gives way to more complex psychological terrain as resistance continues and institutional response intensifies. The secondary phase frequently involves what trauma researchers call "moral injury"—psychological damage from witnessing or participating in events that violate core moral beliefs, particularly when accompanied by institutional betrayal from systems previously trusted. For many advocates, the discovery that respected institutions will defend themselves through deception, character assassination, or procedural manipulation causes deeper distress than direct attacks. This disillusionment can trigger cascading identity questions: if this trusted institution operates this way, what other foundational assumptions might be incorrect? This questioning, while potentially enlightening, carries significant psychological costs. Prolonged advocacy frequently produces specific cognitive and emotional patterns that require active management. Hypervigilance—a state of constant alertness to threat—serves protective functions during active conflict but becomes psychologically damaging when chronically activated. Similarly, rumination—repetitive analysis of past events and anticipated futures—can provide useful insights but depletes cognitive resources when excessive. Most challenging is identity narrowing—the gradual reduction of self-concept to advocacy-related aspects that diminishes life satisfaction and ultimately undermines effectiveness by limiting perspective and flexibility. Research on sustainable advocacy suggests specific practices that mitigate these costs while maintaining commitment. Temporal boundaries—designated periods completely separated from advocacy work—preserve psychological resources by allowing regular recovery from vigilance demands. Similarly, relationship diversification—maintaining connections with individuals unconnected to the advocacy context—prevents identity narrowing while providing reality-testing from perspectives outside the conflict dynamic. Perhaps most crucial is meaning maintenance—regularly reconnecting with the core values and purposes that initiated advocacy rather than focusing exclusively on tactical battles and institutional responses. The physical dimension of sustained advocacy receives insufficient attention despite its critical importance. Stress physiology research demonstrates that prolonged activism triggers predictable biological responses: elevated cortisol levels, immune system suppression, sleep disruption, and cardiovascular effects. These responses, designed for short-term emergencies, become physiologically damaging when chronically activated. Effective advocates increasingly recognize that physical practices—adequate sleep, exercise, nutritional support, and stress-reduction techniques—represent strategic necessities rather than optional luxuries, preserving the biological resources needed for sustained effectiveness. Perhaps the most challenging aspect of self-care involves navigating the inherent tension between personal wellbeing and advocacy effectiveness. Many advocates experience guilt when prioritizing personal needs, viewing self-care as self-indulgence that betrays their cause and those they hope to help. This perspective, while understandable, ultimately undermines long-term impact by creating cycles of intense commitment followed by burnout and withdrawal. The most effective approach reconceptualizes self-care not as separate from advocacy but as an integral component of strategic effectiveness—maintaining the human resources necessary for sustained impact rather than sacrificing them for short-term intensity. The most sustainable advocates develop what might be called "principled pragmatism"—they remain absolutely committed to core values while demonstrating flexibility about means, timing, and personal involvement. This approach avoids both cynical accommodation and self-destructive idealism by recognizing that the most effective service to principles often requires pacing, strategic withdrawal when necessary, and maintenance of the human capacity required for long-term impact.

Chapter 6: Creating Coalitions: The Power of Collective Action

Individual courage, while essential for initiating challenges to power, rarely succeeds without evolving into collective action. The transition from solitary voice to effective coalition represents perhaps the most crucial inflection point in advocacy trajectories. Understanding the dynamics of this transition illuminates why some challenges to power gain momentum while others remain isolated despite equal moral validity. Coalition formation typically begins through informal connection—individuals recognizing shared concerns and gradually developing communication networks. This initial phase often occurs through what network theorists call "weak ties"—casual connections that bridge different social circles and institutional locations. Research consistently demonstrates that these cross-cutting connections prove more valuable for movement building than "strong ties" within homogeneous groups, as they facilitate information flow across institutional boundaries and prevent early containment of concerns within single organizational units. Successful coalitions develop through predictable stages that require different capacities at each phase. Initial formation demands boundary spanning—identifying potential allies across institutional divisions by focusing on shared concerns rather than pre-existing relationships or complete ideological alignment. The consolidation phase requires frame alignment—developing shared language and conceptual frameworks that accommodate diverse perspectives while maintaining coherent direction. Mature coalitions depend on role differentiation—creating complementary functions that leverage different skills, institutional positions, and risk tolerances among members. The most effective coalitions demonstrate strategic complementarity among participants. Different individuals can serve distinct functions based on their positions, capacities, and vulnerabilities. Those with institutional protection or financial security may appropriately take higher-profile roles; those with specialized knowledge may focus on documentation and analysis; those with communication skills may prioritize message development; those with organizational experience may coordinate logistics. This differentiation contrasts with naive approaches that expect uniform commitment and identical risk-taking from all participants. Perhaps the most challenging aspect of coalition building involves managing inevitable internal tensions without fragmentation. Successful coalitions navigate predictable conflicts: tactical disagreements about timing and methods; representational questions about who speaks for whom; credit distribution concerns about recognition and leadership; and pace differences regarding acceptable timelines for change. Research on movement sustainability suggests that groups that explicitly acknowledge these tensions and develop processes for addressing them significantly outlast those that demand uniform perspectives or suppress internal disagreement. Coalition resilience depends largely on what organizational theorists call "process legitimacy"—the perception that decision-making methods fairly incorporate diverse perspectives even when specific outcomes disappoint some participants. Groups that establish transparent processes for addressing disagreements, distributing leadership opportunities, and evaluating tactics maintain cohesion despite tactical setbacks. This procedural focus contrasts with fragile coalitions that maintain unity only through charismatic leadership or continuous victory, both unsustainable in prolonged challenges to power. Technology has transformed coalition-building possibilities while introducing new vulnerabilities. Digital platforms facilitate connection across geographic and institutional boundaries, allowing previously isolated concerns to recognize their systemic nature. However, these tools also create security vulnerabilities, documentation risks, and surveillance opportunities that previous generations of advocates never faced. The most sophisticated coalitions now blend digital connectivity with selective in-person interaction, using technology strategically while recognizing its limitations for building the trust required for high-risk collective action. The most effective coalitions balance tactical focus with vision maintenance—addressing immediate concerns while connecting them to broader principles that sustain commitment through inevitable setbacks. This dual focus prevents both impractical utopianism and demoralizing incrementalism by demonstrating how specific achievable actions advance fundamental values. Groups that master this balance create sustainable paths for challenging power by connecting individual courage to collective capacity, transforming momentary bravery into durable change.

Chapter 7: Legacy and Change: Measuring Impact Beyond the Moment

Assessing the impact of challenges to power raises profound questions about how change occurs and what constitutes meaningful success. Traditional metrics often fail to capture the complex, non-linear ways that individual acts of courage influence institutional and social systems. A more sophisticated understanding of impact considers multiple timeframes, diverse causal pathways, and the relationship between visible outcomes and invisible transformations. The most immediate impact of challenging power often appears discouraging when measured by conventional metrics. Formal policies rarely change quickly; institutional leaders typically respond defensively; and the original concerns may remain unaddressed long after initial challenges. However, this surface-level assessment overlooks crucial processes occurring beneath visible outcomes. Organizational researchers identify multiple "latency effects" that develop before formal changes: increased internal discussion of previously unmentionable topics; quiet policy reviews initiated to prevent future exposure; gradual alignment shifts among middle management; and subtle resource reallocation toward problematic areas. These changes, while invisible to outsiders, often represent the first stages of significant reform. Impact analysis becomes more complex when considering information diffusion effects. When challenges to power become public, they create informational ripples that extend far beyond the original context. These effects include precedent awareness—other potential challengers learning that resistance is possible; problem recognition—previously isolated concerns becoming recognizable as patterns; resource discovery—individuals facing similar issues finding language, tactics and supportive networks; and audience expansion—concerns previously confined to affected subgroups becoming visible to broader constituencies. These knowledge effects frequently produce impact in unexpected locations and timeframes, making direct causation difficult to trace but no less significant. Legacy assessment must also consider narrative transformation—changes in how situations are understood and discussed. Successful challenges to power often shift acceptable discourse by introducing new language, questioning previously unexamined assumptions, and legitimizing alternative perspectives. Once established, these narrative shifts create lasting changes in how institutions perceive problems and evaluate solutions. Importantly, narrative impacts often outlast policy reversals—even when specific reforms are later undone, the conceptual frameworks that made them possible rarely disappear completely, creating foundations for future action. Perhaps the most underappreciated impact dimension involves identity transformation among those who witness courage rather than directly engaging in it. Psychological research consistently demonstrates that observing moral courage significantly increases observers' assessment of their own capacity to act similarly. This "vicarious moral elevation" creates diffuse but substantial changes in perceived possibility, often inspiring action in completely different contexts years after the original events. This phenomenon explains why many who later challenge power cite earlier examples of courage as formative influences, creating intergenerational impact chains invisible to conventional assessment. Sophisticated impact evaluation must also consider counterfactual scenarios—what would have happened without the challenge. Even when immediate outcomes appear disappointing, challenges to power frequently prevent worse alternatives by increasing the perceived costs of problematic behavior. This deterrent effect operates through what game theorists call "preference falsification"—institutional actors becoming more cautious not because their true preferences change but because the perceived risks of acting on those preferences increase. These prevention effects, while impossible to measure directly, represent real impact that conventional metrics miss entirely. The most profound legacy of challenging power may be its demonstration that institutional arrangements presented as inevitable are actually contingent and changeable. This fundamental shift in perception—from seeing systems as fixed realities to understanding them as human constructions subject to revision—creates possibility spaces that transcend specific outcomes. Even "failed" challenges contribute to this deeper transformation by revealing the constructed nature of authority and the potential for alternative arrangements. A comprehensive understanding of impact ultimately requires embracing paradox—acknowledging that the most significant effects of challenging power often manifest indirectly, unpredictably, and across timeframes that transcend individual experience. This perspective suggests measuring success not by immediate victories but by contribution to evolving understandings, relationships, and possibilities that reshape what future generations perceive as both problematic and possible.

Summary

The journey of standing against powerful institutions reveals a profound truth about human agency: our capacity to effect change depends less on initial power than on psychological resources that can be intentionally developed. When individuals recognize moral clarity as a skill rather than an inherent trait, they unlock the ability to maintain conviction despite institutional pressure designed to induce doubt and compliance. The most successful challengers combine this unwavering commitment to principles with strategic flexibility about methods, timing, and coalitions, allowing them to navigate complex social and organizational landscapes without compromising core values. The ripple effects of courage extend far beyond immediate outcomes, operating through information diffusion, narrative transformation, and identity shifts that continue long after original events. This understanding transforms how we evaluate impact, suggesting that even apparently unsuccessful challenges may create essential conditions for future change by expanding perceived possibilities and connecting previously isolated concerns. What ultimately emerges from these stories is a practical vision of moral agency that balances idealism with pragmatism, allowing ordinary people to contribute meaningfully to social transformation without requiring either naive optimism or cynical compromise.

Best Quote

Review Summary

Strengths: The book contains inspiring stories of individuals overcoming challenges, such as the Miracle on Ice, a nurse's dedication during the pandemic, and a woman's role in forecasting D-Day.\nWeaknesses: The review criticizes the book for excessive focus on Andrew Cuomo, USA gymnastics, and COVID, making it feel niche. The author's personal anecdotes are seen as detracting from the overall message. The narrative is perceived as self-centered, particularly in the context of political commentary, which the reviewer finds annoying and misaligned with the book's intended theme.\nOverall Sentiment: Mixed\nKey Takeaway: While the book offers some inspirational stories, its focus on certain political issues and the author's personal involvement detracts from its broader appeal and intended message of highlighting diverse heroic efforts.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.