Categories

Nonfiction, Sports, Biography, Memoir, Audiobook

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2020

Publisher

William Morrow

Language

English

ASIN

0062992066

ISBN

0062992066

ISBN13

9780062992062

File Download

PDF | EPUB

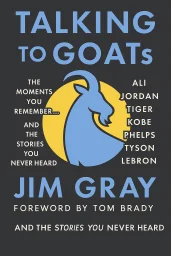

Talking to GOATs Plot Summary

Introduction

Imagine standing at the edge of the ancient Forum in Rome, surrounded by marble columns and grand temples that once witnessed the birth of Western civilization. The Roman Empire, at its height, stretched from the foggy shores of Britain to the scorching deserts of Egypt, creating one of history's most remarkable political and cultural achievements. Yet this same empire, seemingly invincible for centuries, eventually crumbled and transformed, leaving us with profound questions about how great powers rise, rule, and ultimately decline. The story of Rome offers us a fascinating lens through which we can examine timeless questions about governance, military power, and cultural identity. Through examining Rome's journey from a small Italian settlement to a Mediterranean superpower and its eventual transformation, we gain insights into how societies balance expansion with stability, how leadership succession impacts governmental stability, and how cultural integration shapes imperial identity. Whether you're a history enthusiast curious about ancient civilizations or someone interested in understanding the patterns that shape world powers throughout time, the Roman experience provides valuable lessons about ambition, governance, and the complex forces that build and break empires.

Chapter 1: Foundations: From Monarchy to Republic (753-509 BCE)

The story of Rome begins with myth intertwined with archaeological reality. According to Roman tradition, the city was founded in 753 BCE by Romulus, who, along with his twin brother Remus, was supposedly raised by a she-wolf. While modern historians view this tale skeptically, archaeological evidence confirms that settlements on Rome's seven hills indeed date back to the 8th century BCE. These early communities gradually coalesced into a unified settlement strategically positioned along the Tiber River, providing both defensive advantages and commercial opportunities. The early Roman society developed under the influence of the sophisticated Etruscan civilization to the north. For approximately two and a half centuries, Rome was ruled by kings, with seven monarchs traditionally recognized in Roman historical accounts. The last of these kings, Tarquinius Superbus (Tarquin the Proud), was remembered as a tyrant whose excesses ultimately proved intolerable to the Roman people. His son's rape of a noblewoman named Lucretia became the catalyst for revolution. In 509 BCE, led by Lucius Junius Brutus, the Romans overthrew their monarchy and established a republic—a pivotal moment that would shape Roman identity for centuries to come. This nascent republic established core institutions that would endure throughout Roman history. Power was deliberately distributed to prevent any single individual from gaining absolute control. Two annually elected magistrates called consuls shared executive authority, while the Senate, composed of aristocratic elders, provided guidance and continuity. The popular assemblies gave ordinary citizens some voice in governance, though political power remained firmly in the hands of patrician families. This complex system created a balance between competing interests while allowing for effective governance and military leadership. Early Republican Rome faced existential threats from neighboring peoples, including the Etruscans, Sabines, and Volscians. These conflicts forged a distinctly Roman approach to warfare and diplomacy. The Romans developed a disciplined military system based on the legion, a flexible fighting unit that would eventually conquer the Mediterranean world. Equally important was Rome's innovative approach to conquered peoples. Rather than simply subjugating defeated enemies, Rome often extended various forms of citizenship and alliance, gradually incorporating them into the Roman state. This policy of integration, though not applied universally, became a cornerstone of Roman expansion. The early Republic also witnessed intense internal conflict between the patricians (aristocratic families) and plebeians (common citizens). The plebeians, essential for Rome's economy and military, demanded greater political rights and protection from aristocratic abuse. Through a series of secessions—essentially general strikes where plebeians withdrew from the city—they gradually secured important concessions. The creation of plebeian tribunes with veto power, the codification of laws in the Twelve Tables around 450 BCE, and the eventual opening of high offices to plebeians represented significant democratic advances, though Rome never became a full democracy in the modern sense. By the end of this formative period, Rome had established the fundamental characteristics that would define its rise to power: resilient political institutions, military discipline, diplomatic flexibility, and a capacity for internal reform. These qualities would serve Rome well as it faced greater challenges and opportunities in the centuries ahead, transforming from a city-state into the dominant power of the Mediterranean world.

Chapter 2: Republican Expansion and Social Tensions (509-133 BCE)

Following the establishment of the Republic, Rome embarked on a remarkable journey of territorial expansion that would transform it from a regional power in central Italy to the dominant force in the Mediterranean world. This expansion began with the gradual conquest of the Italian peninsula. After defeating the Etruscans to the north, Rome faced a serious threat from the Gauls, who sacked the city around 390 BCE. Rather than collapsing, Rome rebounded from this disaster with remarkable resilience. Through a combination of military victories and shrewd diplomacy, the Romans gradually subdued the Samnites, Etruscans, and Greek colonies of southern Italy, bringing the entire peninsula under their control by 265 BCE. Rome's success in Italy stemmed from its innovative approach to conquered territories. Unlike many ancient powers that simply extracted tribute from subjugated peoples, Rome developed a sophisticated system of alliances and citizenship. Some conquered communities received full Roman citizenship, while others became "Latin allies" with limited rights. This flexible approach created a network of loyal communities throughout Italy, providing Rome with manpower for its armies and a buffer against external threats. As the Roman statesman Cicero would later observe, "We have overcome all the nations by offering them our friendship and by protecting them once they became our subjects." The First Punic War (264-241 BCE) marked Rome's first major conflict beyond the Italian peninsula. Carthage, a powerful maritime empire based in North Africa, controlled Sicily, Sardinia, and parts of Spain. The war began over competing interests in Sicily and forced Rome, traditionally a land power, to develop a navy. After a grueling 23-year struggle, Rome emerged victorious, acquiring Sicily as its first province. The Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) presented an even greater challenge when the brilliant Carthaginian general Hannibal invaded Italy, inflicting several devastating defeats on Roman armies. Despite these setbacks, Rome's political system remained stable, and its Italian alliance network held firm. Eventually, Roman general Scipio Africanus took the fight to Africa, defeating Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 BCE. With Carthage subdued, Rome turned its attention eastward to the Hellenistic kingdoms that had emerged from Alexander the Great's empire. Through a series of wars against Macedonia, the Seleucid Empire, and various Greek states, Rome established dominance over the eastern Mediterranean. Unlike in Italy, Rome initially ruled these eastern territories indirectly, allowing local elites to maintain power while acknowledging Roman supremacy. By 133 BCE, Rome controlled territories spanning from Spain to Asia Minor, transforming from a city-state into an empire in all but name. This remarkable expansion brought unprecedented wealth flowing into Rome, dramatically transforming Roman society. Public buildings became more magnificent, adorned with marble and decorated with art looted from Greek cities. The aristocratic elite competed to display their wealth through lavish homes, gardens, and patronage of the arts. Greek culture, once viewed with suspicion, became fashionable among the Roman upper classes, who hired Greek tutors for their children and collected Greek artworks. As the historian Polybius noted, "The Romans, after the conquest of Macedonia, abandoned themselves with singular facility to the worship of the gods of Greece." However, this prosperity was not evenly distributed, creating dangerous social tensions. The traditional Roman farming class faced increasing economic pressure as cheap grain from conquered provinces flooded Italian markets, and wealthy landowners assembled vast estates (latifundia) worked by slaves captured in foreign wars. Many small farmers, unable to compete, sold their lands and migrated to Rome, creating an urban underclass dependent on patronage and public handouts. Meanwhile, the Italian allies who had contributed significantly to Rome's victories received few benefits from imperial expansion, breeding resentment that would eventually erupt into conflict.

Chapter 3: Civil Wars and the Republic's Fall (133-27 BCE)

The century between 133 and 27 BCE witnessed Rome's traumatic transition from republic to empire, a period marked by escalating political violence, civil wars, and the emergence of powerful individuals who ultimately overshadowed the republican institutions. This transformation began with the reform efforts of Tiberius Gracchus, elected tribune in 133 BCE. Alarmed by the decline of the small farmer class that traditionally formed the backbone of Rome's legions, Tiberius proposed redistributing public land to landless citizens. His methods, however, violated political norms by bypassing the Senate, and he was ultimately murdered by a mob of senators. Ten years later, his brother Gaius Gracchus attempted more comprehensive reforms before meeting a similar fate. These events shattered the long-standing taboo against political violence in Rome. The military reforms of Gaius Marius further undermined republican stability. Facing manpower shortages during the war against Jugurtha of Numidia, Marius opened military service to landless citizens, creating a professional army loyal to their generals rather than to the state. Soldiers now looked to their commanders for land grants upon retirement, creating dangerous personal loyalties. As the historian Sallust observed, "From this time on, the army began to value private gain above the public good." This transformation of the military would have profound consequences as ambitious generals increasingly used their armies as tools for political advancement. The Social War (91-88 BCE) erupted when Rome's Italian allies, long denied the full benefits of citizenship despite their contributions to Roman expansion, revolted. Though Rome eventually prevailed militarily, the conflict forced the extension of citizenship to all free Italians, fundamentally altering the character of the Roman state. This war was quickly followed by the first full-scale civil war between Marius and his rival Sulla, who in 82 BCE became the first Roman general to march on Rome itself. Sulla's subsequent dictatorship, though voluntarily relinquished after constitutional reforms, set a dangerous precedent for the use of military force in political disputes. The following decades saw the rise of extraordinary individuals who dominated Roman politics through a combination of military success, personal charisma, and strategic alliances. Pompey the Great secured unprecedented commands against Mediterranean pirates and in the East, while Marcus Licinius Crassus leveraged his immense wealth for political influence. The young Julius Caesar, meanwhile, built his reputation through military victories in Gaul. These three men formed the First Triumvirate in 60 BCE, an informal alliance that effectively controlled the Roman state. However, this uneasy balance collapsed following Crassus's death in 53 BCE, leading to civil war between Caesar and Pompey. Caesar's victory in this conflict and his subsequent appointment as dictator perpetuo (dictator for life) in 44 BCE marked the effective end of republican government, though the institutions remained in name. His assassination by senators hoping to restore the Republic instead triggered another round of civil wars. Caesar's adopted son Octavian (later Augustus) formed the Second Triumvirate with Mark Antony and Lepidus, defeating the assassins before turning against each other. The final showdown came at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, where Octavian defeated the forces of Antony and Cleopatra, becoming the undisputed master of the Roman world. The late Republic's collapse stemmed from fundamental contradictions that had developed within the Roman system. Republican institutions designed for a city-state proved inadequate for governing a vast empire. Economic disparities undermined social cohesion, while provincial wealth created opportunities for ambitious individuals to build personal power bases. The professional army transferred loyalty from the state to successful generals. Perhaps most importantly, the traditional aristocratic consensus that had sustained republican government fractured under the pressures of imperial expansion and social change. As Cicero lamented shortly before his death, "The Republic, the Senate, the courts of justice are mere empty words. They retain no reality, all such blessings have been lost."

Chapter 4: Pax Romana: The Golden Age (27 BCE-180 CE)

The establishment of the Principate by Augustus (formerly Octavian) in 27 BCE marked the beginning of Rome's most stable and prosperous era, commonly known as the Pax Romana or "Roman Peace." Augustus's genius lay in his ability to create a de facto monarchy while maintaining the facade of republican government. He held no formal royal title, instead accumulating various republican offices and powers that, in combination, gave him complete control. The Senate continued to meet, magistrates were still elected, and Augustus presented himself merely as the "first citizen" (princeps). As he famously declared, "I found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble"—a statement that referred not only to physical transformation but also to the stability he brought after decades of civil war. Augustus established a system that would endure for centuries, creating the framework for imperial governance. He reorganized the provinces, taking personal control of those with significant military forces while leaving the more peaceful regions under senatorial administration. The army was professionalized and stationed primarily along the frontiers, with special units (the Praetorian Guard) protecting the emperor in Rome. A new civil service gradually developed to administer the vast empire more efficiently. Perhaps most importantly, Augustus established clear precedents for imperial succession, adopting his stepson Tiberius and preparing him for leadership. Though not without flaws, this system provided the essential continuity that had been lacking in the late Republic. The first two centuries of imperial rule witnessed remarkable stability and prosperity across the Mediterranean world. The emperors who followed Augustus—particularly Vespasian, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius—generally governed with competence and restraint. Under Trajan (98-117 CE), the empire reached its greatest territorial extent, incorporating Dacia (modern Romania) and briefly extending into Mesopotamia. Hadrian (117-138 CE) consolidated these gains, building defensive fortifications like Hadrian's Wall in Britain and focusing on internal development rather than further conquest. This period saw the emergence of what historian Edward Gibbon would later describe as a time when "the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous." The Pax Romana created unprecedented economic integration across the Mediterranean basin and beyond. A vast network of roads, harbors, and shipping routes facilitated trade from Britain to Egypt, from Spain to Syria. Common currency, legal standards, and the absence of internal barriers allowed merchants to operate across enormous distances. Agricultural production increased through the spread of techniques and crops suited to local conditions. Cities flourished throughout the provinces, adorned with forums, temples, bathhouses, and amphitheaters built according to Roman models but often funded by local elites eager to display their wealth and status. As the Greek orator Aelius Aristides observed, "The whole world prays that this empire may endure forever." Roman culture during this period reflected both the assimilation of Greek influences and the development of distinctly Roman forms. Literature flourished under imperial patronage, with poets like Virgil and Horace creating works that both celebrated Roman achievements and explored universal human themes. Architecture and engineering reached new heights, exemplified by structures like the Pantheon with its revolutionary concrete dome. Roman law evolved into a sophisticated system that influenced legal thinking for centuries to come. Perhaps most significantly, the empire facilitated cultural exchange among its diverse populations, creating a cosmopolitan Mediterranean civilization that transcended ethnic and regional boundaries. The Pax Romana also witnessed significant social and religious developments that would shape the empire's future. Citizenship was gradually extended to provincial elites, creating a trans-Mediterranean governing class with shared interests and values. Women, particularly in the upper classes, enjoyed greater legal and economic rights than in many earlier societies. New religious movements spread throughout the empire, including mystery cults from the East and, most consequentially, Christianity. Though initially persecuted as a potentially subversive sect, Christianity gradually gained adherents across social classes and regions, establishing organizational structures that would later prove crucial to its survival and expansion.

Chapter 5: Crisis, Adaptation and Division (180-395 CE)

The death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 CE marked a turning point in Roman history, initiating a period of increasing instability that would ultimately transform the empire beyond recognition. His son Commodus, unlike the "Five Good Emperors" who had adopted their successors based on merit, proved to be an erratic ruler obsessed with gladiatorial combat and his own divine status. His assassination in 192 CE triggered a civil war that revealed a dangerous structural weakness in the imperial system: the lack of a clear mechanism for peaceful succession. The victor, Septimius Severus, established a new dynasty that increasingly relied on military power rather than senatorial consent, accelerating the militarization of Roman governance. The third century CE brought unprecedented challenges that strained the empire to its breaking point. Between 235 and 284 CE, a period known as the "Crisis of the Third Century," Rome experienced approximately 26 claimants to the imperial throne, most of whom were military commanders elevated by their troops and subsequently assassinated. This political chaos coincided with external pressures as Germanic tribes along the Rhine and Danube frontiers and the newly aggressive Sassanid Persian Empire in the east launched increasingly effective attacks. Economic difficulties compounded these problems, with rampant inflation following the debasement of Roman currency and disruptions to trade networks due to insecurity. The empire seemed on the verge of collapse. The crisis was temporarily resolved through the reforms of Diocletian (284-305 CE), who fundamentally restructured the Roman state. Recognizing that the empire had grown too large for a single ruler to manage effectively, he established the Tetrarchy—a system of four co-emperors governing different regions. He also separated civil and military authority, expanded the bureaucracy, reformed taxation, and attempted to stabilize the economy through price controls. While many of these measures proved effective in the short term, they also created a more regimented society with diminished local autonomy and increased state demands on the population. As one contemporary observed, "There came to be more receivers than givers, and the farmers' resources were exhausted by the enormous burden of taxes." Constantine the Great (306-337 CE) built upon Diocletian's administrative reforms while making two crucial changes that would shape the empire's future. First, he reunified imperial authority under a single ruler and established Constantinople as a new capital in the east, strategically positioned between Europe and Asia. Second, and perhaps more consequentially, he legalized Christianity and actively supported the Church, beginning the transformation of the Roman Empire into a Christian state. By the end of the fourth century, Emperor Theodosius I had made Christianity the official religion, prohibiting pagan practices that had defined Roman culture for a millennium. This religious revolution fundamentally altered how Romans understood their place in the world and the purpose of the state. The growing divergence between the eastern and western halves of the empire became increasingly apparent during this period. The east, with its urbanized population, commercial wealth, and defensible borders, proved more resilient in the face of external threats and internal challenges. The west, with its longer frontiers, less developed urban centers, and greater exposure to Germanic incursions, struggled to maintain stability. These differences were formalized when Theodosius I died in 395 CE, dividing the empire between his sons Arcadius (east) and Honorius (west). Though theoretically still a single empire, the two halves would never again be effectively united under one ruler, setting the stage for their dramatically different fates in the following centuries. This period of crisis and adaptation demonstrates Rome's remarkable resilience but also the limits of imperial power. Through administrative innovation, military reorganization, and religious transformation, the Roman state managed to survive challenges that might have destroyed less adaptable political systems. However, these changes came at a cost—the empire that emerged from the crisis was fundamentally different from the one that had preceded it. More centralized, more militarized, and increasingly Christian, this transformed Roman state would face the challenges of the fifth century with new strengths but also new vulnerabilities. The division between east and west, initially an administrative convenience, would ultimately lead to dramatically different historical trajectories for the two halves of the Roman world.

Chapter 6: The Western Empire's Transformation (395-476 CE)

The western provinces faced increasing pressure from Germanic peoples displaced by nomadic movements originating in Central Asia. Rather than simply raiding Roman territory, these groups now sought to settle within the empire's borders. The Romans increasingly relied on these same peoples as military allies (foederati) and recruited them into the army, blurring the distinction between Romans and "barbarians." The watershed moment came in 376 CE when a large group of Goths, fleeing from the Huns, was admitted into the empire as refugees. Mistreatment by Roman officials led to rebellion, culminating in the Battle of Adrianople (378 CE), where Emperor Valens was killed and his army destroyed—a shocking demonstration of Roman vulnerability. The fifth century witnessed the gradual disintegration of direct Roman authority in the west. In 410 CE, Rome itself was sacked by Visigoths under Alaric—an event that sent shockwaves throughout the Mediterranean world. St. Augustine, responding to claims that Christianity had weakened Rome, began writing his influential work "The City of God," which reframed Roman history within a Christian narrative of divine providence. By mid-century, various Germanic kingdoms had established themselves within former Roman territories: Visigoths in Spain and southern Gaul, Vandals in North Africa, Burgundians and Franks in Gaul, and eventually Ostrogoths in Italy. The formal end came in 476 CE when the Germanic general Odoacer deposed the last Western Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, and declared himself King of Italy without bothering to appoint a new emperor. Yet this "fall" was less a sudden collapse than a complex transformation. Many aspects of Roman civilization persisted under new leadership. Germanic kings adopted Roman administrative practices, legal concepts, and cultural forms. The Catholic Church preserved Roman organizational structures and Latin literacy. Local Roman elites often continued to govern at the municipal level. What disappeared was not Roman civilization itself but rather the centralized imperial state in the west. As historian Peter Brown observed, "The end of the Western Empire was less like the fall of a great tree than like a forest fire that clears away the dominant vegetation, allowing smaller plants that had been growing in the shade to flourish in the sunlight." The new Germanic kingdoms that emerged from this transformation represented a hybrid of Roman and Germanic elements. The Ostrogothic king Theodoric, who ruled Italy from 493 to 526 CE, maintained Roman administrative structures, employed Roman officials, and presented himself as a legitimate successor to the emperors. The Frankish king Clovis, who united much of Gaul under his rule around 500 CE, converted to Catholic Christianity rather than the Arian form practiced by most Germanic peoples, facilitating cooperation with the Gallo-Roman population. The Visigothic kingdom in Spain gradually developed a sophisticated legal system that combined Roman principles with Germanic customs. These rulers recognized the practical value of Roman institutions and the prestige associated with Roman traditions. The Catholic Church emerged as a crucial institution during this transitional period, preserving elements of Roman culture while adapting to new political realities. Bishops often assumed leadership roles in cities abandoned by imperial officials, managing essential services and representing their communities to Germanic rulers. Monasteries preserved classical texts through copying manuscripts, maintaining a tenuous link to the intellectual traditions of the ancient world. The papacy gradually developed as a political as well as spiritual authority, filling some of the vacuum left by imperial retreat. As Pope Gelasius I wrote to Emperor Anastasius in 494 CE, there were "two powers by which this world is chiefly ruled: the sacred authority of the priesthood and the royal power"—a formulation that would influence medieval political thought for centuries. The transformation of the Western Roman Empire demonstrates both the fragility and the durability of complex political systems. The centralized imperial state proved vulnerable to a combination of external pressures and internal weaknesses, yet many elements of Roman civilization—law, administration, religion, language, and urban life—persisted in altered forms. The "fall" of Rome was less an abrupt catastrophe than a gradual process of adaptation and hybridization, producing new political and cultural formations that would eventually evolve into medieval European civilization. This perspective challenges simplistic narratives of decline and collapse, suggesting instead that the end of the Western Empire represented one phase in the ongoing evolution of Mediterranean and European society.

Chapter 7: Byzantium: The Eastern Continuation (476-1453 CE)

While the western provinces fragmented into Germanic kingdoms, the eastern half of the Roman Empire not only survived but thrived, evolving into what modern historians call the Byzantine Empire—though its citizens continued to identify themselves as Romans (Romaioi) until the very end. This eastern continuation preserved and transformed Roman institutions, law, and culture while adapting to new challenges. The empire's remarkable longevity stemmed from several advantages: a more urbanized and commercially active economy, defensible borders, superior naval power, and a more centralized administrative tradition inherited from the Hellenistic kingdoms that preceded Roman rule in the region. The defining figure in this transformation was Emperor Justinian I (527-565 CE), whose ambitions temporarily reversed the empire's contraction. His general Belisarius reconquered North Africa from the Vandals, Italy from the Ostrogoths, and parts of Spain from the Visigoths, briefly restoring Mediterranean unity under Constantinople's authority. Equally significant were Justinian's internal achievements: the codification of Roman law in the Corpus Juris Civilis, which would later provide the foundation for many European legal systems; the construction of architectural masterpieces like the Hagia Sophia; and the reorganization of provincial administration. However, these accomplishments came at tremendous cost, depleting the treasury and overstretching military resources. As the contemporary historian Procopius noted, "He had an insatiable desire to build, and a passion for tearing down the existing to build something else." The seventh century brought existential threats that fundamentally altered the Byzantine state. The rise of Islam led to the loss of the empire's wealthiest provinces—Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and North Africa—reducing Byzantium to Asia Minor, parts of the Balkans, and southern Italy. Simultaneously, Slavic peoples settled throughout the Balkans, changing the region's ethnic composition. In response to these challenges, Emperor Heraclius (610-641 CE) implemented sweeping reforms, replacing Latin with Greek as the official language and reorganizing the remaining territories into military districts (themes) where soldiers received land in exchange for hereditary service. These changes created a more compact, militarized state that successfully adapted to reduced circumstances. Byzantine civilization reached another peak under the Macedonian dynasty (867-1056 CE), which oversaw territorial expansion, cultural flourishing, and economic revival. The empire reclaimed parts of Syria and Bulgaria, while missionaries like Cyril and Methodius spread Byzantine Christianity and culture to the Slavic peoples, creating the Cyrillic alphabet and laying the foundations for what would later be called the "Byzantine Commonwealth"—a sphere of Orthodox Christian nations influenced by Constantinople. This period also witnessed a remarkable literary and artistic renaissance, with scholars preserving and commenting on classical texts while developing distinctive Byzantine artistic forms, particularly in architecture, mosaics, and icon painting. The relationship between Byzantium and Western Europe grew increasingly strained during this period. The coronation of Charlemagne as "Emperor of the Romans" by Pope Leo III in 800 CE challenged Byzantine claims to be the sole legitimate Roman Empire. Theological disputes, particularly over the authority of the Pope and doctrinal issues like the filioque clause, widened the gap between Eastern and Western Christianity, culminating in the Great Schism of 1054 CE. Cultural and linguistic differences further separated the Greek-speaking, Orthodox east from the Latin-speaking, Catholic west. As Anna Comnena, a Byzantine princess and historian, observed of western crusaders: "The Latins are indeed a race particularly devoted to warfare, violent in attack, and in all ways distinct from the Greeks." The Crusades accelerated this estrangement while creating new threats to Byzantine security. The Fourth Crusade of 1204 CE, diverted from its intended target in the Holy Land, resulted in the sack of Constantinople and the establishment of a short-lived Latin Empire. Though the Byzantines recaptured their capital in 1261 CE, the empire never fully recovered from this catastrophe. The final centuries saw Byzantium reduced to a minor state, gradually losing territory to the rising Ottoman Turks. The end came on May 29, 1453, when Sultan Mehmed II captured Constantinople after a 53-day siege, and the last Byzantine Emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, died fighting on the walls of the city. Despite its ultimate fall, the Byzantine Empire's thousand-year existence represented an extraordinary achievement of cultural continuity and adaptation. It preserved classical knowledge that would later contribute to the Renaissance in Western Europe. Its legal traditions influenced systems from Russia to Greece. Its artistic and architectural styles spread throughout the Orthodox world. Perhaps most importantly, it maintained the idea of a universal Christian empire that combined Roman political concepts with Greek culture and Christian faith—a powerful legacy that would shape European and Middle Eastern history long after Constantinople's fall.

Summary

The epic journey of Rome from a small settlement on the Tiber to a world-spanning empire and its eventual transformation reveals a central tension that defines much of human political organization: the struggle between centralized authority and local autonomy. Throughout Roman history, we see this dynamic playing out—from the early Republic's careful balance of powers, through the imperial system's pragmatic compromises, to the eventual divergence between East and West. Rome succeeded when it found ways to integrate diverse peoples while maintaining effective governance, and it faltered when this balance tilted too far toward either rigid centralization or fragmentation. This tension between unity and diversity, between imperial control and local identity, remains relevant to political systems today. The Roman experience offers several enduring lessons for contemporary societies. First, successful political systems must evolve to address changing circumstances while maintaining core values and institutions—as Rome did during its republican and early imperial phases but failed to accomplish during later periods. Second, military power alone cannot sustain an empire; economic integration, cultural exchange, and some degree of shared identity are equally essential for long-term stability. Finally, the transformation rather than simple "fall" of Rome reminds us that civilizations rarely disappear completely; instead, their ideas, practices, and institutions are adapted and reinterpreted by successor societies. By understanding Rome not as a static entity but as a continuously evolving civilization whose influence extended far beyond its political boundaries, we gain a more nuanced perspective on how societies change over time and how the past continues to shape our present world.

Best Quote

“People will forget what you say, and people will forget what you do, but no one will ever forget the way you make them feel.” ― Jim Gray, Talking to GOATs

Review Summary

Strengths: The book is described as entertaining, with engaging behind-the-scenes stories involving high-profile athletes. The author's enthusiasm is noted as contagious, making the topics enjoyable. The chapter about the author's experiences with his father is particularly moving.\nWeaknesses: The book is criticized for focusing too much on the author’s personal experiences and relationships rather than the lives of the athletes, leading it to resemble a celebrity tabloid. There is a perception of inflated self-importance by the author, particularly regarding his role in LeBron’s “The Decision” and a legal dispute over Tiger Woods footage.\nOverall Sentiment: Mixed\nKey Takeaway: While the book offers entertaining anecdotes and insights into the sports world, it is overshadowed by the author’s focus on his personal experiences and perceived self-importance, which may detract from the expected content about the athletes themselves.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.