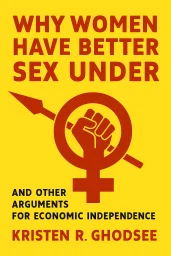

Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism

And Other Arguments for Economic Independence

Categories

Nonfiction, Philosophy, History, Economics, Politics, Audiobook, Feminism, Sociology, Essays, Womens

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2018

Publisher

Bold Type Books

Language

English

ISBN13

9781568588902

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism Plot Summary

Introduction

Unregulated capitalism disadvantages women through structural economic inequalities while socialism offers solutions that lead to greater autonomy and fulfilling relationships. This provocative thesis challenges conventional wisdom about political-economic systems, examining how access to resources shapes gender dynamics at the most intimate level. Drawing on extensive research into state socialist societies of Eastern Europe, alongside comparisons with Western capitalist systems, we see how economic structures directly impact women's daily experiences, from workplace opportunities to romantic relationships. The argument extends beyond abstract policy discussions to examine how economic systems influence our most personal choices. When women have financial independence, stable employment, and social support for care responsibilities, they gain freedom not just in public life but in private relationships as well. The historical experiments of the 20th century, despite their significant flaws, provide valuable insights into alternate ways of organizing society that reduce gender inequality. Rather than embracing these failed systems wholesale, we can extract specific policies that demonstrably improved women's lives and adapt them for democratic contexts, creating societies where human flourishing - including sexual satisfaction - is prioritized over profit maximization.

Chapter 1: Economic Independence: How Socialism Reduces Women's Financial Dependence

Free markets systematically discriminate against women workers, particularly those with reproductive responsibilities. From the earliest days of industrial capitalism, women entered the workforce at a comparative disadvantage - employers perceived them as weaker, less reliable, and secondary earners rather than primary breadwinners. This disadvantage became a self-fulfilling prophecy, as employers could justify paying women less because they had the option of simply hiring men instead. The concept of a "family wage" reinforced this dynamic, with the assumption that women worked for "pin money" while men needed salaries sufficient to support entire households. This economic subordination was not incidental but foundational to capitalist development. Women's unpaid labor in the home subsidized employers' profits by reproducing the workforce at no cost to them. Without control over reproductive choices, education access, or meaningful employment opportunities, women remained financially dependent on male partners or relatives. This dependency created vulnerability and limited women's autonomy in all aspects of life. The doctrine of coverture, which rendered married women essentially the property of their husbands, reflected this economic reality. As recently as the 1950s, West German women could not work outside the home without their husband's permission, and American women could not open bank accounts or obtain credit without male co-signers until the 1970s. Socialist societies approached this problem differently, designing economic systems that incorporated women as full participants rather than subordinate workers. State socialist countries not only encouraged but often mandated women's labor force participation, investing in education and training to prepare women for diverse professions. Countries like Bulgaria, East Germany, and the Soviet Union actively promoted women in traditionally male-dominated fields like engineering, medicine, and even military service. These states also established support systems - childcare, family leave, communal dining facilities - that socialized domestic responsibilities previously borne exclusively by women. The statistics tell a compelling story: by 1975, women comprised nearly 50% of the Soviet workforce and over 43% of workers in Eastern Europe, compared to just 37% in North America and 33% in Western Europe. While gender pay gaps and occupational segregation persisted, women's economic participation in socialist countries significantly exceeded Western levels. Moreover, guaranteed employment, subsidized housing, free healthcare, and universal education meant women were far less dependent on individual male providers for basic security. This economic independence had profound effects on power dynamics within families and relationships. Women could leave unsatisfying or abusive partnerships without facing destitution. They could pursue education and careers without requiring a husband's permission or support. Even today, countries with stronger social democratic policies like Denmark and Sweden show greater gender equality in economic outcomes than more market-oriented economies like the United States, suggesting that certain socialist approaches continue to benefit women in mixed economic systems. The collapse of state socialism after 1989 demonstrated the fragility of these gains. As Eastern European countries rapidly privatized their economies, women's economic position deteriorated dramatically. Many were pushed out of the workforce into traditional domestic roles, losing the economic independence they had gained under socialism. This regression highlights how economic systems fundamentally shape women's opportunities and constraints, regardless of formal legal rights.

Chapter 2: Labor and Motherhood: Socialist Policies Supporting Working Women

Motherhood creates unique challenges in competitive labor markets. As my colleague's experience with a tech employee who eventually quit after having a baby illustrates, employers often engage in what economists call "statistical discrimination" - making decisions based on group averages rather than individual characteristics. Since women as a group are more likely to reduce work hours or take time off for family responsibilities, individual women face discrimination regardless of their personal plans or circumstances. This discrimination stems from the biological reality of pregnancy and childbirth, combined with social expectations that women will be primary caregivers. In capitalist labor markets, employers have strong incentives to avoid hiring or promoting women of childbearing age, particularly for positions requiring significant investment in training. When employers bear the full cost of worker absence during maternity leave, while all the social benefits of raising the next generation accrue to society broadly, the rational economic decision is to discriminate against potential mothers. Socialist theorists recognized this problem early. By the late 19th century, thinkers like Lily Braun were already proposing solutions like state-funded "maternity insurance" that would distribute the costs of reproduction across society rather than concentrating them on individual women and employers. Braun argued that since society as a whole benefits from children who become future workers, citizens, and taxpayers, the costs of supporting their early development should be socialized rather than privatized. Eastern European socialist states implemented various versions of these policies after World War II. In Bulgaria, for example, the 1971 constitution guaranteed women maternity leaves and job protection. By 1973, Bulgarian women enjoyed 120 days of fully paid maternity leave plus an additional six months at the national minimum wage, with the option of unpaid leave until their child reached age three. Crucially, these leaves counted toward pension eligibility, and jobs were protected throughout. Czechoslovakia introduced similar provisions in 1956, guaranteeing women eighteen weeks of paid, job-protected leave. Beyond leave policies, socialist states invested in extensive networks of public childcare facilities. East Germany built crèches for infants and kindergartens for older children, making it possible for mothers to return to work without sacrificing their children's well-being. While the quality of these facilities varied, they represented a systematic attempt to socialize childcare rather than treating it as each individual woman's private responsibility. Nordic countries adopted similar approaches, explaining why Scandinavian female labor force participation rates were second only to Eastern Europe during the Cold War era. The socialist approach recognized that differences in reproductive biology make treating men and women identically in labor markets impossible. Instead, these states implemented policies that accommodated these differences while promoting economic independence. By contrast, the United States only outlawed pregnancy discrimination in 1978 and did not mandate unpaid family leave until 1993 - and still lacks national paid leave policies that virtually every other country provides. When Eastern European countries transitioned to market economies after 1989, many of these supports disappeared or were drastically reduced. Public childcare facilities closed, and new private options were unaffordable for many families. Some governments extended parental leaves but at much lower compensation rates and without job protections. The result was a process economists call "refamilization" - pushing women back into traditional domestic roles while cutting public expenditures. This transition shows the different priorities of socialist versus capitalist approaches to reconciling work and family responsibilities.

Chapter 3: Political Representation: Advancing Women in Leadership Positions

Despite significant progress in educational achievement and workforce participation, women remain dramatically underrepresented in leadership positions across democratic capitalist societies. In the United States, women make up nearly half the workforce but hold only 21% of corporate board seats and 11% of top executive positions. Political representation shows similar disparities - as recently as 2015, women comprised just 19% of the U.S. Congress, compared to 44% in Sweden and 48% in Iceland. This persistent leadership gap doesn't stem from differences in ability or ambition. Research consistently shows that most people recognize no inherent differences between men and women's leadership capabilities. In some areas - such as honesty, mentoring ability, and willingness to compromise - surveys indicate that people actually consider women superior leaders. Rather, the gap reflects deeply embedded social expectations about authority and decision-making being inherently masculine domains. Socialist societies approached this problem through systemic intervention rather than waiting for gradual cultural evolution. In countries like Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany, political parties established formal quotas for women's representation in parliaments and party structures. Though these measures sometimes created more symbolic than substantive representation in authoritarian systems, they nonetheless normalized the idea of women in positions of authority. Socialist states also placed women in highly visible leadership roles to demonstrate their commitment to gender equality, as with the Soviet decision to make Valentina Tereshkova the first woman in space in 1963. This symbolic representation had practical impacts. When girls saw women like Elena Lagadinova (Bulgaria), Vida Tomšič (Yugoslavia), or Ana Pauker (Romania) holding ministerial positions, it expanded their sense of possibility. Eastern European countries also directed women into professional fields like medicine, law, and science at much higher rates than Western counterparts. A 2018 Financial Times analysis revealed that eight of the ten European countries with the highest rates of women in technology fields were former Eastern Bloc nations - a direct legacy of socialist educational policies. The most effective approach to increasing women's leadership representation appears to be formal quotas - a policy socialist states pioneered but democratic countries have increasingly adopted. Norway's requirement that 40% of corporate board seats be held by women has dramatically increased female representation, and similar policies in France and Iceland have yielded comparable results. Countries with voluntary targets or no requirements show much slower progress. In 2017, the European Commission proposed an EU-wide law requiring large companies to implement 40% quotas for women on corporate boards, recognizing that without structural intervention, progress remains glacial. However, quotas must be carefully designed to avoid becoming merely symbolic. In single-party socialist states, women's presence in parliaments often masked their exclusion from inner circles where real decisions were made. Even today, quotas that place women in leadership positions without addressing underlying barriers - such as unequal domestic responsibilities or differential performance evaluations - may create the appearance of equality without its substance. A comprehensive approach to advancing women's leadership requires both structural interventions like quotas and cultural shifts in how we conceptualize authority. The socialist experience demonstrates that greater representation is possible but also that formal inclusion doesn't automatically translate to equal influence. Democratic societies can adapt these approaches by implementing targeted quotas while simultaneously addressing broader social barriers that impede women's advancement.

Chapter 4: Sexual Economics: How Capitalism Commodifies Intimacy

Sexual economics theory proposes that heterosexual interactions can be analyzed as market exchanges where women sell access to sexuality and men purchase it with monetary or non-monetary resources. In this framework, women have historically controlled sexual access because their desire is purportedly lower than men's, creating an asymmetrical market where women can demand compensation in various forms - from marriage commitments to material support or social advancement. While controversial, this theory provides a revealing lens for examining how economic systems shape intimate relationships. Capitalism intensifies this market dynamic by reducing all human interactions to potential transactions. As Marx and Engels observed in 1848, capitalism "has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous 'cash payment'... it has resolved personal worth into exchange value." This commodification extends to sexuality and relationships, where partners assess each other's value based on what benefits they might extract. In highly unequal market societies, women with limited economic options may rationally view their sexuality as a resource to exchange for financial security or social advancement. Sexual economics theorists acknowledge that women's economic independence fundamentally alters this market dynamic. When women have direct access to education, employment, and resources, they no longer need to exchange sexual access for basic security. Empirical research supports this relationship - in countries with greater gender equality, people report more casual sex, younger ages of sexual initiation, and greater acceptance of premarital sexuality. This correlation suggests that economic independence allows women to pursue relationships based on desire rather than necessity. This transformation threatens traditional power structures. Conservative critics have explicitly blamed women's economic advancement for decreasing marriage rates and weakening male motivation to achieve. In their view, when women lower the "price" of sexual access by not requiring marriage or long-term commitment, men lose incentive to pursue education, stable employment, and social responsibility. These critics argue for restricting women's reproductive freedom and economic opportunities to restore traditional sexual marketplaces where women exchange access to their bodies for lifetime financial support. The sexual economics framework reveals how capitalist logic infiltrates our most intimate spheres. When relationships become transactions, partners constantly calculate their relative advantage, leading to resentment and manipulation. Men who believe they are "purchasing" access through financial provision may feel entitled to control women's sexuality and behavior. Women dependent on men's resources must perform emotional labor and sexual compliance regardless of their authentic desires. This dynamic corrupts intimacy by introducing power imbalances and ulterior motives into relationships that ideally would be based on mutual attraction and genuine connection. Early socialist theorists recognized this corrupting influence. Alexandra Kollontai argued that under capitalism, women's economic dependence transformed sexuality into a commodity exchange. "The buying and selling of caresses," she wrote, "destroys the sense of equality between the sexes, and thus undermines the basis of solidarity." She envisioned a socialist society where economic independence would allow people to form relationships based on authentic mutual attraction rather than material necessity. This vision recognized that substantive sexual freedom requires economic security - that consent cannot be truly freely given when basic survival depends on maintaining a relationship.

Chapter 5: Beyond Commodification: Socialist Approaches to Sexual Liberation

State socialist societies provided natural experiments in how economic systems affect intimate relationships. While these regimes often maintained conservative sexual mores in official discourse, their economic policies unintentionally created conditions for different relationship dynamics. Russian sociologists Anna Temkina and Elena Zdravomyslova documented this evolution through interviews with Soviet women across generations. They found that while the early Soviet "silent generation" primarily viewed sex through a procreative lens, women who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s increasingly described sexuality in terms of romance and interpersonal connection rather than economic exchange. The most dramatic example emerged in East Germany, where state policies explicitly promoted women's economic independence alongside public messaging about gender equality. East German sexologists conducted extensive research comparing sexual satisfaction between East and West Germans, finding consistently higher rates of reported sexual fulfillment among East German women. A 1990 comparative study revealed that when asked if they felt "satisfied" after their last sexual encounter, 75% of East German women agreed compared to just 46% of West German women. Similarly, 82% of East German women reported feeling "happy" after sex, versus only 52% of West German women. These differences appeared linked to East German women's economic autonomy, which created more balanced power dynamics in relationships. As sociologist Ingrid Sharp explained, East German women could leave unsatisfying relationships without economic consequences: "Divorce in the GDR was relatively simple and had few financial or social consequences for either partner... The fact that women instigated the majority of divorce proceedings was heralded as a sign of their emancipation." When women didn't need relationships for financial security, they could choose partners based on compatibility and mutual satisfaction rather than economic calculation. Similar patterns appeared in other socialist states. Czechoslovakian sexologists concluded that "good sex" was only possible when men and women were social equals, and they linked women's economic independence directly to sexual fulfillment. Hungarian researchers in the 1970s found that young people strongly disapproved of transactional sexual relationships, viewing prostitution as particularly objectionable precisely because socialist society met women's basic needs, eliminating any legitimate reason to commodify sexuality. The transition to capitalism after 1989 reversed many of these dynamics. Temkina and Zdravomyslova documented the emergence of an "instrumental script" in post-Soviet Russia, where young women increasingly viewed their sexuality as a resource to be exchanged for material benefits. The rapid growth of "gold digger academies" in Moscow, where women paid substantial fees to learn techniques for attracting wealthy sponsors, exemplified this return to market-based sexual relations. Similarly, East Germans frequently expressed nostalgia for pre-1989 sexual culture, describing it as "more genuine and loving, more sensual, and more gratifying—and less grounded in self-involvement—than West German sex." This evidence suggests that decommodifying sexuality creates conditions for more authentic and mutually satisfying relationships. When people choose partners based on genuine attraction rather than economic calculation, both report greater fulfillment. Recent studies in Western contexts support this connection - research with German couples found that perceptions of fairness in household labor division correlated with increased sexual satisfaction for both partners. Similarly, American heterosexual couples who share childcare more equitably report higher relationship quality and sexual frequency.

Chapter 6: Democratic Socialism: Voting Power and Women's Political Future

The political enfranchisement of women represents a relatively recent development in human history, yet already faces backlash from those who recognize its transformative potential. Following the 2016 US presidential election, when demographic analysis showed that Donald Trump would have won decisively if only men voted, some supporters promoted the hashtag #RepealThe19th - suggesting rescinding women's constitutional right to vote. This reaction reflects growing recognition that women's voting patterns differ systematically from men's in ways that could fundamentally reshape political priorities. Research consistently shows that women, particularly single women, are more likely to support candidates advocating expanded social services and stronger safety nets. Economists John Lott and Lawrence Kenny correlated the growth of US government spending in the early twentieth century with the spread of women's suffrage, concluding that women voters drove expansion of social programs. This pattern emerges because women rationally support policies that mitigate their economic vulnerability - particularly since they often bear disproportionate responsibility for unpaid care work while facing discrimination in labor markets. This voting tendency explains the intense hostility toward women's political participation from certain quarters. Conservative commentator Ann Coulter candidly admitted this motivation in 2007: "If we took away women's right to vote, we'd never have to worry about another Democrat president. It's kind of a pipe dream, it's a personal fantasy of mine." Men's rights activists explicitly argue that female suffrage has destroyed Western civilization by enabling socialist policies, with one writing that repealing the Nineteenth Amendment would mean "within just one national election, every single leftist party would be crushed." Rather than fearing this potential, women should recognize and embrace their collective political power. By 2020, millennial voters will constitute the largest demographic block in the American electorate, with women making up half that cohort. Polling consistently shows younger Americans, particularly young women, holding more favorable views of socialism than previous generations. A 2017 survey found that 43% of millennials had favorable opinions of socialism, compared to just 32% with positive views of capitalism. These demographic trends represent an unprecedented opportunity for electoral transformation. The democratic process offers a peaceful path toward implementing policies that would significantly improve women's lives: universal healthcare, affordable childcare, paid family leave, expanded public employment, and stronger protections for labor rights. Northern European social democracies demonstrate that such policies can function effectively within democratic systems while dramatically reducing gender inequality. Countries like Denmark, Sweden, and Finland consistently rank highest globally in measures of women's wellbeing precisely because they combine democratic governance with robust social supports. Conservative forces will inevitably attempt to suppress this potential political realignment through voter suppression, gerrymandering, and fearmongering about socialism's historical failures. They deploy simplistic equations between any redistributive policy and Stalinist totalitarianism, hoping to prevent nuanced discussion of which socialist policies could be effectively implemented within democratic frameworks. These tactics reveal their recognition that democratic majorities, particularly women voters, increasingly favor economic policies that distribute resources more equitably. The future political landscape depends on whether women recognize and exercise their collective voting power. If millennial and Generation Z women mobilize politically around their economic interests, they could fundamentally reshape policy priorities toward greater social support and economic security. This transformation would benefit not just women but entire communities that suffer under unregulated capitalism's instabilities and inequalities.

Summary

The evidence from both historical socialist experiments and contemporary social democracies reveals that women's economic independence fundamentally transforms gender relations across all spheres of life. When women access education, employment, healthcare, and social support independent of their relationships with men, power dynamics shift from transaction toward authentic connection. This transformation manifests in workplace opportunities, political representation, family relationships, and even sexual satisfaction - creating societies where women exercise genuine autonomy in both public and private life. The path forward does not require replicating failed authoritarian systems but rather extracting specific policies that demonstrably improved women's lives and implementing them within democratic frameworks. Universal healthcare, affordable childcare, paid parental leave, job security, and gender quotas in leadership positions all contribute to women's independence without requiring political repression. As younger generations increasingly question capitalism's failures to deliver broad-based wellbeing, women's collective political power offers the potential to build more equitable societies where human relationships can flourish beyond the logic of market exchange. The resulting transformation would liberate not just women but everyone from the dehumanizing effects of economic systems that reduce human worth to monetary value.

Best Quote

“When women enjoy their own sources of income, and the state guarantees social security in old age, illness, and disability, women have no economic reason to stay in abusive, unfulfilling, or otherwise unhealthy relationships.” ― Kristen R. Ghodsee, Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: And Other Arguments for Economic Independence

Review Summary

Strengths: The book aims to challenge myths about Eastern European state socialism and advocates for more redistributive and regulatory economic policies to benefit women, which is considered a laudable goal.\nWeaknesses: The review criticizes the book for lacking discussion on working-class women's activism and for focusing on elite women in leadership roles, which the reviewer sees as contrary to socialist feminist ideals. Additionally, the book is said to offer a distorted view of socialism by equating it with expanded welfare states, referencing Eastern Bloc countries and Scandinavia.\nOverall Sentiment: Critical\nKey Takeaway: The reviewer finds the book's approach to socialism and feminism problematic, particularly its focus on elite women and its portrayal of socialism, which they argue does not align with the principles of socialist feminism.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.