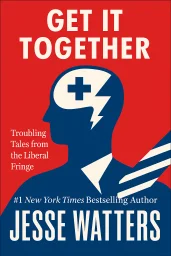

Get It Together

Troubling Tales from the Liberal Fringe

Categories

Nonfiction, Politics, Audiobook

Content Type

Book

Binding

Kindle Edition

Year

2024

Publisher

Broadside e-books

Language

English

ASIN

B0BSFS5FTX

ISBN

006325204X

ISBN13

9780063252042

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Get It Together Plot Summary

Introduction

Have you ever wondered what drives someone to believe the unbelievable? What makes a person abandon mainstream society to embrace ideas most would consider extreme or even dangerous? Across America, ordinary people are adopting extraordinary beliefs - from professors advocating open borders to activists toppling statues, from eco-sexuals finding intimacy with nature to those who believe work itself is oppressive. Behind these radical positions often lie deeply human stories of trauma, disconnection, and the search for meaning. This journey into America's most eccentric minds reveals that extreme beliefs rarely emerge in isolation. They grow from personal wounds, family dysfunction, and the universal human need for belonging. By understanding the emotional foundations of radical thought, we gain not just insight into others, but valuable perspective on our own vulnerabilities to extreme thinking. Whether you're puzzled by a loved one's political transformation, concerned about growing polarization, or simply curious about the human capacity for unusual beliefs, these stories offer a compassionate window into how pain transforms into conviction - and how empathy might bridge our deepest divides.

Chapter 1: The Professor's Dream: How Trauma Shapes Political Idealism

Joe Carens presents himself as a friendly academic with white hair and beard, clearly amused to be speaking with a Fox News host. Unlike the stereotypical angry activist, Joe is calm and measured as he explains his controversial position: borders should generally be open, and people should be free to settle wherever they choose. As a political science professor at the University of Toronto for 37 years, his academic credentials lend weight to what many would consider a radical stance. Growing up as a middle-class Catholic in Boston, Joe studied theology at Yale Divinity School before losing his faith. He avoided Vietnam by switching to political science, later teaching at Princeton before settling in Toronto. His personal journey included divorce from his first wife and remarriage to a feminist theorist in 1985. Throughout our conversation, Joe maintains the detached demeanor of an academic, retreating to theoretical abstractions when pressed about practical concerns like national security or economic impacts of open borders: "I'm a political theorist, not focusing immediately on debates about public policy." What's particularly revealing is Joe's reluctance to engage with real-world implications. When asked about illegal immigrants who commit crimes, he deflects. When questioned about the economic impact of open borders, he pivots to abstract principles. His academic detachment from reality seems purposeful - he's explicitly "against focusing on what's possible in the world" in favor of theoretical ideals. This approach makes more sense when Joe reveals a traumatic past: "I think I was sexually abused. I don't have clear memories... but it did affect my stance in the world." The conversation takes an unexpected turn as Joe mentions possible abuse connected to the Catholic Church, explaining his "psychological aversion to being in Catholic churches." This revelation provides context for his yearning for fairer institutions - ones that would protect the vulnerable. His striving for universal amnesty and institutional protection makes sense in light of repressed trauma, as does his preference for abstract possibility over practical reality. Joe's story illustrates how personal trauma can shape political idealism. His academic career became a vehicle to reimagine a world without the boundaries and power structures that failed to protect him as a child. While many might disagree with his open borders position, understanding the emotional foundation of his beliefs creates space for empathy. Behind many radical political positions lie personal wounds seeking healing through systemic change - a pattern repeated across the ideological spectrum.

Chapter 2: Rebellion as Identity: When Personal Pain Becomes Ideology

Emily, a beauty and fashion publicist in her thirties, is in the midst of a messy divorce and being sued by her entire family—except her brother. When asked if her lawyers know about our interview, she casually replies, "No, they don't need to know everything." This cavalier attitude is typical of Emily, who spills her life story with volcanic intensity, revealing how personal trauma transformed into political identity. Growing up in what she describes as a "stone, cold mansion—Tim Burton-style," Emily's childhood was marked by rigid rules and an oppressive atmosphere. Her father, a psychiatrist, and her mother, a psychotherapist, created a household filled with prescription medications. "We had drugs, the Prozac, the Viagra all over our house," she recalls. Her father was "incredibly abusive, physically. Only with me," targeting Emily because she had "this voice" that challenged him. The breaking point came when Emily, at fourteen, was "kidnapped in the middle of the night" and sent to a therapeutic boarding school in Utah run by Mormons, where children were stripped of dignity: "You literally don't wear shoes. You don't eat with silverware. You can't watch TV." Emily's rebellion against authority found its perfect outlet during the George Floyd protests. Recently divorced and separated from her children, she discovered Black Lives Matter protests while walking around New York. "That's when I started to find my voice," she explains. "I would just be walking around with my headphones on, and I would see this massive protest, and I just jumped right in." BLM became her new family after being cut off by her father, who disapproved of her activism. Her transformation was complete when she began dating a Black man from the movement and moved to the Bronx projects. "I've never dated a black guy. I've only dated white guys because I was only allowed to date white guys," she says. What's striking about Emily's political conversion is how recent and incomplete it is—she's surprised to learn basic facts about police demographics and struggles to articulate coherent positions. Her left-wing activism isn't built on facts or research but on emotional reactions to her painful upbringing. As she puts it, "I've always felt like kind of a lost child," seeking acceptance she never received at home. When asked if she feels guilty about being white, she admits, "Sometimes I don't like being white." Emily's story reveals how ideology can become a vehicle for rebellion against family trauma. Her embrace of progressive activism isn't primarily about the issues themselves but about rejecting her father's conservative worldview and finding a new community that accepts her. This pattern appears across the political spectrum - people often adopt radical positions as a way to process personal pain and construct a new identity in opposition to those who hurt them. Understanding this emotional foundation doesn't invalidate the beliefs themselves, but it does illuminate why some hold them with such intensity and resistance to contrary evidence.

Chapter 3: The Search for Belonging: Radical Paths to Community

Ayo Kimathi, a self-described "African nationalist," sits across from me with a shaved head and bright, intense eyes. He speaks with authority about his mission to "save the black race" from what he sees as an existential threat. Within forty minutes of our conversation, Ayo begins focusing obsessively on Jews, blaming them for everything from coronavirus to gangsta rap, from the KKK to the NAACP. His radical worldview, while disturbing, makes more sense when understood through the lens of his search for belonging and identity. Raised by a single mother in southeast Washington, DC, Ayo didn't meet his father until he was twenty-seven. "I'll never forget that day because of the excitement of that happening, but he never came that day. That was a rough day," he recalls. This absence left "missing elements" in his personality that he acknowledges shaped his worldview. "I would've been a better man in my estimation had I had a father there, but I probably wouldn't have gone into this," he admits, referring to his black nationalist ideology. The connection between his absent father and his radical beliefs becomes even clearer when Ayo reveals that his own wife left him because he was "so married to the mission of saving my race" that he neglected his family. Ayo's worldview was shaped at Concord Academy, a prestigious prep school where he felt out of place as one of few black students. There, he experienced what he calls "liberal racism" – "a painful racism because it's done with a smile." A formative moment came when a Jewish classmate corrected him in class, teaching him "the lesson of humility." Yet rather than embracing this lesson, Ayo developed a worldview where Jews control everything and are responsible for destroying the black family. What becomes clear is that Ayo has transferred the anger he feels toward his absent father onto an external enemy, blaming Jews for his father leaving, for his marriage ending, for losing his job – accepting no personal responsibility. Despite his hateful rhetoric, there's something wounded about Ayo. When asked what's more powerful, love or hate, he deflects the question. When asked about interracial relationships, he dismisses them entirely. His radical beliefs serve as armor against the pain of abandonment, allowing him to feel powerful rather than vulnerable. By claiming the role of protector of the black race, he's attempting to become the father figure he never had, finding purpose and community in a movement that gives him the sense of belonging he's always craved. Ayo's story illustrates how radical ideologies often provide what mainstream society has failed to offer: a sense of purpose, community, and identity. For those who feel rejected, marginalized, or abandoned, extremist groups can offer ready-made explanations for their suffering and a clear path to redemption. This pattern appears across the ideological spectrum - from religious cults to political extremism - suggesting that addressing the human need for belonging might be more effective than simply countering radical ideas with facts. When people find healthy communities that accept them, the appeal of extremist worldviews often diminishes.

Chapter 4: Digital Bubbles: How Technology Amplifies Extreme Beliefs

Steven Brown (not his real name) is a thin, middle-aged white man with glasses and a goatee who includes his pronouns (he/him) in his bio. A former lawyer, he now works with the Prostasia Foundation, which claims to "protect children" by protecting the "rights and freedoms" of "minor-attracted persons" (MAPs) – a term they prefer over "pedophile." Throughout our conversation, Steven attempts to normalize attraction to minors while maintaining that acting on such attraction is wrong, demonstrating how digital spaces have enabled this type of extremism to flourish. Steven claims that being attracted to minors is something people are born with: "Medically, scientifically, there's some suggestion that it is inborn in a similar way. It develops without any choice." He advocates for using the term "minor-attracted persons" rather than "pedophile" because the latter "in the public's mind means sex offender." More disturbingly, he suggests that attraction to teenagers is normal: "When you get to sixteen-, seventeen-year-olds, it's not unusual at all for adult men to find teenagers attractive." His organization lobbies against restrictions on child pornography, including computer-generated images and child-sized sex dolls, arguing, "If it doesn't harm a child, then it shouldn't be treated the same way." When pressed about practical concerns, Steven's arguments become increasingly troubling. Asked whether he would allow a minor-attracted person to babysit his children (ages eleven and fifteen), he initially evades the question before finally admitting, "If they told me or if I had some reason to know that they were attracted to the ages of children that they would be babysitting, then I would probably choose someone else." This admission contradicts his earlier insistence that MAPs pose no inherent danger. Steven mentions that his organization receives funding from anonymous donors and claims they've been "targeted" for their views. The interview reveals how digital spaces have transformed fringe beliefs. Before the internet, individuals with extreme views were isolated, limiting their ability to organize and develop sophisticated ideological frameworks. Now, technology allows like-minded individuals to find each other, develop specialized language to normalize their beliefs, and create organizations that appear legitimate. Steven's group uses academic-sounding language, cites selective "research," and frames their position as protecting "human rights" - all strategies made possible by digital connectivity. This case demonstrates how technology doesn't just connect extremists – it provides tools for them to rebrand harmful ideologies as reasonable positions deserving of public consideration. Online spaces create filter bubbles where extreme ideas can be reinforced without challenge, gradually shifting what adherents consider acceptable. As digital platforms continue to evolve, we must recognize how they can amplify fringe beliefs by providing both the means to spread these ideas and the shield of anonymity to protect those promoting them. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for addressing extremism in the digital age.

Chapter 5: The Trauma Connection: Personal Wounds Behind Radical Views

Mike, a Native American from the Anishinabe tribe (commonly known as Chippewa) living in Minneapolis, harbors a deep resentment toward America that culminated in a dramatic act of protest: toppling a Christopher Columbus statue following the George Floyd riots. Rather than jail time, a judge sentenced him to "a hundred hours of community service to teach and educate in the schools on the genocide that happened here in order to create the United States and Minnesota." Behind Mike's radical actions lies a lifetime of personal and generational trauma that shaped his worldview. "I grew up in a household of drugs and alcohol," he explains. When he was six, the Indian Relocation Program moved his family from the reservation to the St. Paul projects. Over the next decade, they moved back and forth nine times, creating a childhood of instability and disconnection. This personal instability mirrors the historical displacement of Native peoples, creating layers of trauma that fuel Mike's anger. When teaching students about American history, he tells them: "Those pilgrims, those pioneers, and those settlers, for the most part, were extreme white Christian terrorists." Yet he's careful to add, "The first thing I always say to people is that, 'You did not do it.' I have a message for the white people or the non-Native people, whenever I give a speech: 'You did not do it because you were not here.'" The source of Mike's anger isn't just historical injustice but ongoing inequality. "The animosity comes from the fact that you all are benefiting from what happened. And me and my family are still hurting from what happened," he explains. He rejects calls to "get over it," comparing his people's experience to other historical traumas: "What if I said, 'The Holocaust happened a long time ago. Get over it'? Whenever I hear 9/11, the very next word is 'never forget.' If it's okay for them to never forget 9/11, how come I'm supposed to forget what happened to us?" Mike believes Native Americans were "made by the creator to live in creation" and that Western civilization is fundamentally at odds with this natural state. He compares his people to wolves taken from the wild: "If you took a pack of wolves and you wanted to tame them, you take the puppies away, and you put them in a zoo... Now, today, you go to the zoo, and you see the wolves there. They look like wolves. They sound like wolves. If I took them and put them back into the wilderness where their ancestors came from, they are going to die." This case illuminates how personal and historical trauma can transform into radical political views. Mike's toppling of the Columbus statue wasn't just a political statement but an expression of generations of pain and displacement. While many might disagree with his actions, understanding the trauma that informs them offers insight into how personal wounds shape political convictions. This pattern appears across ideologies - from environmental activists to religious fundamentalists - suggesting that addressing unhealed trauma might be as important as countering radical ideas themselves. When people feel their suffering has been acknowledged and addressed, the need for extreme expressions of anger often diminishes.

Chapter 6: Nature as Salvation: Finding Meaning in Environmental Connection

Hannah, an eco-sexual in her thirties with big blue eyes and a healthy natural glow, defines her identity as "somebody who engages with the earth or nature looking for pleasure." With the earnestness of a spiritual guide, she explains that eco-sexuality isn't just "about people having sex with trees" but rather "an acknowledgment of the intersectionality of social justice issues" and "a deep expression of what it means to be wild in our own bodies in society." Her unusual relationship with nature reveals how people increasingly seek meaning and connection through environmental engagement as traditional social bonds weaken. Growing up in rural Indian Land, South Carolina, Hannah spent "hours and hours" of her childhood "running around in creeks, in the forests, playing with rocks and building forts." This early connection to nature evolved into something more profound after she became a wilderness guide. "I really started to see how interconnected humans are with nature and how we are reflected in the natural world," she explains. After completing a two-year program studying human sexuality, her work shifted into "specializing in sex education with this lens of Earth-based holistic incorporated into it." For Hannah, eco-sexuality manifests in various sensory experiences with nature. "Something as simple as sitting on your porch in a rocking chair and feeling a cool summer breeze come by and the hairs on your skin standing up, that is eco-sexuality," she says. She describes lying in the sun on a beach and feeling its warmth as a form of "temperature play" similar to what some practice in intimate settings. More actively, she uses plants for sensory stimulation: "There's different plants that feel differently on my skin. Something that we see in bedrooms all the time are roses... If you touch the stem, they're spiny and thorny, and there's a kink tool that you roll on your skin that elicits a similar thorny feeling." Hannah's connection to nature goes beyond physical sensation. She describes it as spiritual, with roots in paganism and Earth-based religions. "Earth is like a heaven on Earth to me. It is our heaven. We get to walk around in it every day. It's so beautiful," she says with genuine reverence. This spiritual dimension helped her overcome depression: "I was really depressed for a long time, and nature really brought me back to my body and to this realm to Earth. When I saw the beauty in the world that was around me, I had some recognition that I am made of bone, which is made of soil and stardust." Hannah's story illustrates how humans increasingly seek meaning through nature as traditional social structures decline. In an age of digital disconnection, environmental connection offers a tangible alternative - one that engages all senses and provides a sense of belonging to something larger than oneself. While her specific practices may seem unusual, the underlying yearning for connection, meaning, and sensory experience reflects a broader human need that many feel is unmet in our modern world. As society becomes more technologically mediated, we may see more people developing nature-based identities and practices as a way to reclaim their sense of embodiment and belonging in the world.

Chapter 7: Understanding Without Agreement: Bridging Ideological Divides

Tyler appears on my Zoom with a Christmas tree in the background, even though it's not yet Thanksgiving. "I couldn't wait," he tells me with a grin. "I'm just so excited." Tyler is a drag queen, and he's flirting with me. He's fully done up with makeup and styled hair, but also sports a beard, making his biological sex unmistakable. Our conversation about his life and controversial performances demonstrates how understanding can bridge divides without requiring agreement. "Tell me a little bit about the beard situation," I ask. "Well," he explains, "I am a boy more often than I am a lady, and I felt like it was a way that I could stand out from my peers and also still be true to my quirky, authentic self." Tyler works as an inventory manager at a furniture retailer by day, but his passion is performing in drag. His colleagues know about his double life – most have attended his shows. Tyler identifies as gay (not transgender) and lives in Salt Lake City, Utah. When I ask about his drag persona, he clarifies: "I do prefer to use female pronouns when I'm dressed as a woman, when I'm presenting more female... I do identify as a man, and I'm a man in a dress and a wig." Our conversation turns to the controversial topic of drag shows for children. Tyler has performed in what he calls "family-friendly" drag shows three times. He insists these performances are appropriate and beneficial: "I think that what we're doing is really healthy for our community, and it's a wonderful form of outreach for people that don't otherwise get to see themselves represented." When asked about the sexualized nature of some drag performances involving children, Tyler acknowledges that some performers have "made mistakes" but deflects by comparing drag to cheerleaders or mainstream entertainment. What emerges during our conversation is Tyler's personal story. Growing up, he "knew that I wasn't like other boys my age. Not being into balls, and trucks, and cars, and sports. Enjoying playing dress-up and playing with dolls or singing, dancing." He tried to "present normal" to avoid bullying. Most revealing is Tyler's relationship with his brother, who plays for a Major League Baseball team. "He's two years younger than I am," Tyler says. When asked if growing up with a star athlete brother was difficult, he admits, "Yeah, it definitely was. It still is a little bit, honestly." Despite his brother's success, Tyler has never attended any of his baseball games – and his brother has never been to one of his drag shows. This sibling rivalry seems to have shaped Tyler's identity and career choice: "That's where my competitive spirit comes from." Tyler's story illustrates how understanding can bridge divides without requiring agreement. While many might object to drag performances involving children, seeing the human being behind the makeup – a person shaped by childhood experiences, family dynamics, and a search for identity – creates space for empathy. Tyler isn't just a political talking point but a complex individual navigating his place in the world. His story reminds us that behind radical expressions of identity often lie universal human experiences: sibling rivalry, the desire for acceptance, and the search for authentic self-expression. By focusing on these shared human elements, we can maintain dialogue across deep disagreements.

Summary

The journey through America's most eccentric minds reveals a profound truth: extreme beliefs rarely emerge in isolation, but rather grow from the fertile soil of personal trauma, social disconnection, and the human need for meaning. From the eco-sexual finding spiritual connection through nature to the climate activist blocking highways, these individuals aren't simply "crazy" - they're responding to genuine human needs in ways that have veered far from the mainstream. Next time you encounter someone with beliefs that seem incomprehensible, pause before dismissing them entirely. Ask what pain or need might be driving their worldview. Practice genuine curiosity about how they arrived at their position, even if you strongly disagree with it. And perhaps most importantly, strengthen your own connections to community, purpose, and meaning through balanced, healthy channels - the best protection against ideological extremism isn't argument but fulfillment. By understanding the human factors that drive fringe beliefs, we gain not just insight into others, but valuable perspective on our own vulnerabilities to extreme thinking in an age of increasing polarization.

Best Quote

“from Boston. Like most Massholes, he loved hearing himself talk.” ― Jesse Watters, Get It Together: Troubling Tales from the Liberal Fringe

Review Summary

Strengths: The reviewer appreciates Jesse's perspective and finds the book easy to read and fascinating. They commend Jesse for effectively pointing out societal issues and for his excellent job in analyzing fringe individuals. The epilogue is particularly praised for summarizing the book well.\nWeaknesses: The reviewer notes a loss of interest halfway through the book due to the extreme nature of the subjects discussed. They also suggest that some subjects require mental health care, indicating a potential lack of depth or sensitivity in addressing these issues.\nOverall Sentiment: Mixed\nKey Takeaway: While the book is engaging and offers insightful analysis of fringe activists, the extreme nature of the subjects may detract from sustained interest, and there is a need for compassion and depth in addressing mental health aspects.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.