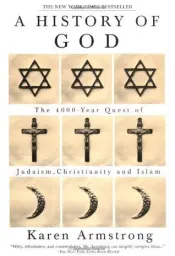

A History of God

The 4000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam

Categories

Nonfiction, Philosophy, Fiction, History, Religion, Spirituality, Classics, Historical Fiction, Literature, Theology, Islam, Christianity, Faith, American, Book Club, Historical, Novels, Classic Literature, Literary Fiction, Class

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2004

Publisher

Gramercy

Language

English

ASIN

0517223120

ISBN

0517223120

ISBN13

9780517223123

File Download

PDF | EPUB

A History of God Plot Summary

Introduction

The concept of God stands as one of humanity's most profound and enduring ideas, evolving dramatically across millennia of human civilization. In the scorching deserts of ancient Mesopotamia, early humans gazed at the stars and sensed divine presence in natural forces, worshipping multiple deities who controlled different aspects of their world. Yet over centuries, this polytheistic worldview gradually transformed into something revolutionary—the belief in a single, all-powerful deity who transcended nature itself. This remarkable journey from many gods to one God represents one of the most significant intellectual and spiritual transformations in human history, reshaping how entire civilizations understood their place in the cosmos. This historical exploration takes us through the winding path of monotheism's development—from tribal deities bound to specific territories, through the revolutionary insights of Hebrew prophets, to the sophisticated theological systems developed by philosophers and mystics. We'll witness how political upheavals, cultural exchanges, and intellectual revolutions repeatedly transformed conceptions of the divine across Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. For anyone fascinated by the evolution of human thought, the history of religion, or the deep questions that have animated spiritual seekers throughout time, this journey offers invaluable insights into how our understanding of ultimate reality has evolved alongside our growing comprehension of ourselves and our universe.

Chapter 1: Tribal Beginnings: From Polytheism to Early Monotheism (1800-586 BCE)

The journey toward monotheism began in a world teeming with gods. Around 1800 BCE, the ancient Near East was dominated by polytheistic belief systems where deities were closely associated with natural forces and tribal identities. In Mesopotamia, Enlil controlled the wind, while Ishtar governed fertility and warfare. In Egypt, Ra journeyed across the sky each day as the sun god, while Osiris ruled the underworld. These gods were not abstract concepts but personalities with desires, jealousies, and conflicts—essentially superhuman versions of their worshippers. The revolutionary concept that would eventually become monotheism emerged gradually among the Hebrew people. According to biblical tradition, Abraham received a call from a deity who demanded exclusive worship—not yet a denial of other gods' existence, but a commitment to serve only one. This relationship was formalized through a covenant, establishing a pattern that would define Hebrew religious identity. The Exodus from Egypt around 1250 BCE (whether historical or mythological) became the defining narrative of this relationship—Yahweh was portrayed not primarily as a nature deity but as a god who acted in history, liberating an oppressed people. Archaeological evidence paints a more complex picture than biblical accounts suggest. Excavations at Israelite sites reveal figurines of the goddess Asherah alongside symbols of Yahweh, indicating that early Hebrew religion was not strictly monotheistic but rather monolatrous—worshipping one god while acknowledging others. Inscriptions from Kuntillet Ajrud refer to "Yahweh and his Asherah," suggesting some Israelites viewed their god as having a divine consort. The biblical prophets' frequent condemnations of idol worship and "going after other gods" confirm that exclusive devotion to Yahweh was an ongoing struggle rather than an established reality. The critical turning point came with the Hebrew prophets of the 8th-6th centuries BCE. Figures like Amos, Hosea, and Isaiah radically reinterpreted Yahweh not merely as Israel's tribal deity but as the universal God of justice who ruled all nations. The prophet Amos shocked his audience by declaring that Yahweh had led not only the Israelites from Egypt but also the Philistines from Caphtor and the Arameans from Kir—a revolutionary claim that God worked through all peoples. This universalizing tendency accelerated during the traumatic Babylonian exile (586-538 BCE), when the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple forced profound theological reconsideration. The anonymous prophet known as Second Isaiah, writing during the exile, articulated the most explicit monotheistic claims yet: "I am the first and I am the last; besides me there is no god." This wasn't merely tribal loyalty but a universal claim about reality itself—that a single divine source underlay all existence. By the time the exiles returned to rebuild Jerusalem, monotheism had become the defining feature of Jewish identity, though it would continue to develop through encounters with Persian, Greek, and Roman thought in subsequent centuries. This transformation from polytheism to monotheism represented more than a numerical reduction in deities. It fundamentally altered how humans understood reality—not as the product of competing divine powers but as the creation of a single, coherent intelligence. This conceptual revolution would eventually reshape the religious landscape across much of the world, providing the foundation for Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, while establishing patterns of thought that continue to influence billions of people today.

Chapter 2: Prophetic Revolution: The Hebrew Transformation (800-200 BCE)

Between 800 and 200 BCE, Hebrew religious thought underwent a profound transformation that would permanently alter the trajectory of monotheism. This period witnessed the emergence of the classical prophets—Amos, Hosea, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and others—who radically reinterpreted the nature of God and religious obligation. These figures were not primarily fortune-tellers but social critics who claimed divine authority to challenge kings, priests, and ordinary people with uncomfortable truths about justice and faithfulness. The prophet Amos, a shepherd from Judah who preached in the northern kingdom of Israel around 750 BCE, exemplified this prophetic revolution. At a time of prosperity and military success, Amos condemned the wealthy for exploiting the poor: "They sell the righteous for silver, and the needy for a pair of sandals." Most shockingly, he proclaimed that God would punish Israel for its injustices, using the Assyrian empire as his instrument. This represented a radical departure from traditional tribal religion, where gods were expected to support their people unconditionally. For Amos, Yahweh's covenant with Israel meant responsibility, not privilege. The Babylonian exile (586-538 BCE) catalyzed the final stage in this transformation. With the Temple destroyed and the people displaced, religious identity could no longer depend on land, monarchy, or sacrificial worship. The anonymous prophet known as Second Isaiah articulated a universal vision of God who controlled all nations and whose purposes extended to all peoples: "It is too small a thing for you to be my servant to restore the tribes of Jacob... I will also make you a light for the Gentiles, that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth." This universalizing tendency transformed Yahweh from a national deity to the God of all creation. During this period, the Hebrew scriptures began to take their final form. The Torah (the first five books) was compiled, combining earlier traditions with new theological perspectives. The Priestly source contributed the majestic account of creation in Genesis 1, where God creates through word alone rather than through conflict with rival deities as in Mesopotamian myths. This text emphasized God's transcendence while affirming the goodness of the material world—a significant departure from some contemporary religious systems that viewed matter as inherently corrupt. The prophetic emphasis on ethical monotheism—the belief that God demands justice and compassion rather than merely ritual observance—became central to Jewish identity. Micah summarized this ethical focus: "What does the Lord require of you but to do justice, love kindness, and walk humbly with your God?" This vision of religion as primarily ethical rather than ritualistic would profoundly influence both Christianity and Islam in later centuries. The prophets established that true worship consisted not merely in sacrifice but in creating a just society that reflected divine values. By 200 BCE, Judaism had developed into a religion centered on scripture rather than sacrifice, on ethical monotheism rather than ritual, and on a God who was both transcendent and intimately involved in human affairs. This transformation laid the groundwork for religious developments that would eventually transcend ethnic and national boundaries. The prophetic emphasis on justice, compassion, and the universal sovereignty of God created a religious vision adaptable to diverse cultures and historical circumstances—a vision that would ultimately reshape the spiritual landscape of much of the world.

Chapter 3: Philosophical Synthesis: Greek Reason Meets Biblical Faith (300 BCE-300 CE)

The period from 300 BCE to 300 CE witnessed a remarkable intellectual convergence as Greek philosophical thought encountered biblical monotheism, creating sophisticated new understandings of God that would shape Western religious thought for millennia. This synthesis began in Alexandria, Egypt, where a large Jewish community engaged with Hellenistic culture while maintaining their religious identity. The translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek (the Septuagint) around 250 BCE made Jewish ideas accessible to the Greek-speaking world and simultaneously introduced Jews to Greek philosophical vocabulary. Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE-50 CE) stands as the most important figure in this early synthesis. A devout Jew and accomplished Greek philosopher, Philo interpreted the Hebrew scriptures through Platonic concepts. He described God as utterly transcendent—beyond human comprehension, without qualities or attributes that humans could understand directly. To bridge the gap between this transcendent deity and the material world, Philo developed the concept of the Logos (divine Word or Reason) as an intermediary principle. This philosophical framework allowed him to interpret biblical anthropomorphisms (God walking in the garden, God's anger) as metaphorical accommodations to human understanding rather than literal descriptions. The emergence of Christianity in the first century CE accelerated this philosophical-religious synthesis. The Gospel of John, written around 100 CE, begins with a deliberate echo of both Genesis and Greek philosophy: "In the beginning was the Logos, and the Logos was with God, and the Logos was God... and the Logos became flesh and dwelt among us." This identification of Jesus with the philosophical principle of Logos represented a profound innovation, suggesting that the abstract divine principle had become incarnate in human history. As Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire, educated converts brought their philosophical training to bear on understanding their new faith. Justin Martyr (c. 100-165 CE), a Platonist philosopher who converted to Christianity, argued that Greek philosophy had been a preparation for the gospel—that Socrates and Plato had glimpsed aspects of divine truth that found their fulfillment in Christ. Clement and Origen of Alexandria developed sophisticated allegorical interpretations of scripture that incorporated Platonic and Stoic concepts while maintaining Christian distinctiveness. The Neoplatonic school, founded by Plotinus in the third century CE, provided another crucial philosophical framework for monotheistic thought. Plotinus described an ineffable One from which all reality emanated in descending levels of being. This vision of divine transcendence combined with immanence through emanation influenced Christian, Jewish, and later Islamic theology. Augustine of Hippo (354-430), perhaps the most influential Christian theologian of the early church, incorporated Neoplatonic concepts into his understanding of God, describing the divine as the unchanging, eternal Good that transcends time and space while remaining intimately present to creation. This philosophical synthesis transformed monotheism from a primarily narrative and ethical tradition into one with sophisticated metaphysical foundations. It provided conceptual tools for addressing questions about God's relationship to time, space, and matter; about divine providence and human freedom; and about how finite humans could know an infinite deity. While this intellectual framework made monotheism more accessible to educated elites throughout the Mediterranean world, it also created tensions between philosophical abstraction and the more personal, narrative-based understanding of God in scripture—tensions that would generate creative theological solutions in the centuries to come.

Chapter 4: Trinity and Tawhid: Christian and Islamic Conceptions (30-800 CE)

Between 30 and 800 CE, two distinctive understandings of divine unity emerged that would shape world history: the Christian doctrine of the Trinity and the Islamic concept of Tawhid (absolute oneness). These theological developments occurred against the backdrop of massive political and cultural transformations—the fall of the Roman Empire, the rise of Byzantium, and the explosive expansion of Islam across the Middle East, North Africa, and beyond. Christianity began as a Jewish movement centered on Jesus of Nazareth, whom his followers came to see as the promised Messiah. After his crucifixion around 30 CE, the early Christian community experienced what they interpreted as his resurrection, leading them to attribute divine status to Jesus while maintaining their monotheistic heritage. This paradox—how Jesus could be divine without compromising the oneness of God—drove centuries of intense theological debate. The Apostle Paul described Jesus as "the image of the invisible God" and taught that through his death and resurrection, Jesus had fundamentally altered humanity's relationship with the divine. By the fourth century, theological controversies about Jesus's precise relationship to God reached a critical point. Arius, a priest of Alexandria, taught that the Son was a created being, subordinate to the Father—a position that preserved divine unity but diminished Christ's status. In opposition, Athanasius insisted on the full deity of Christ. The Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, convened by Emperor Constantine, sided with Athanasius, declaring Jesus to be "of one substance with the Father." Later councils extended this reasoning to the Holy Spirit, eventually formulating the doctrine of the Trinity—one God existing eternally as three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This Trinitarian understanding represented a radical innovation in monotheistic thought. Unlike the strict unity emphasized in Judaism, the Christian God was conceived as inherently relational, existing eternally as a community of love. Gregory of Nazianzus captured this paradoxical understanding: "No sooner do I conceive of the One than I am illumined by the splendor of the Three; no sooner do I distinguish the Three than I am carried back to the One." This conception would profoundly influence Western thought, providing a framework for understanding unity-in-diversity that extended beyond theology to philosophy, politics, and art. Three centuries later, Islam emerged in Arabia with a powerful reassertion of divine unity. Muhammad, receiving revelations from 610 CE until his death in 632, proclaimed a message of strict monotheism against the polytheism of his Arabian context. The Quran repeatedly emphasizes tawhid—the absolute oneness of God: "Say: He is Allah, the One and Only; Allah, the Eternal, Absolute; He begets not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him." This uncompromising monotheism explicitly rejected both polytheism and the Christian doctrine of the Trinity. Despite this fundamental difference, Islamic theology developed in dialogue with Christian and Jewish thought. As Islam spread rapidly across formerly Christian and Zoroastrian territories, Muslim scholars encountered sophisticated theological traditions. The Mu'tazilite school emphasized divine justice and human free will, while the Ash'arites stressed God's absolute power and sovereignty. These debates paralleled earlier Christian theological controversies but reached different conclusions, reflecting Islam's distinctive emphasis on divine unity as the fundamental principle. By 800 CE, these two conceptions of divine unity—Trinitarian and Tawhid—had become defining features of their respective traditions. Their differences would contribute to political and military conflicts, but also to rich intellectual exchanges as scholars across traditions engaged with each other's ideas. The philosophical sophistication of these theological systems demonstrates how the concept of monotheism continued to evolve in response to new questions and cultural contexts, generating diverse interpretations of divine unity that would shape world history for centuries to come.

Chapter 5: Mystical Pathways: Experiencing the Divine Beyond Dogma (800-1500)

Between 800 and 1500 CE, as theological systems became increasingly complex and institutionalized, mystical movements emerged across Judaism, Christianity, and Islam that emphasized direct experience of the divine beyond intellectual formulations. These mystical traditions developed remarkably similar approaches despite their different theological contexts, suggesting a universal dimension to spiritual experience that transcended doctrinal boundaries. In Islam, Sufism emerged as a response to what some perceived as excessive legalism in mainstream religious practice. Early Sufis like Rabia al-Adawiyya (d. 801) emphasized selfless love of God rather than fear of punishment or hope of reward. The Persian poet Rumi (1207-1273) expressed this orientation in his famous lines: "Not Christian or Jew or Muslim, not Hindu, Buddhist, Sufi or zen. Not any religion or cultural system... My place is placeless, a trace of the traceless." Sufis developed spiritual practices including dhikr (remembrance of God through repetition of divine names) and sama (spiritual concerts that could induce ecstatic states). The Spanish-born Sufi theorist Ibn Arabi (1165-1240) articulated one of the most sophisticated mystical theologies in any tradition. His concept of wahdat al-wujud (unity of being) suggested that nothing truly exists except God, with the world being a manifestation of divine attributes. For Ibn Arabi, every religion contained aspects of truth, as he famously wrote: "My heart has become capable of every form: it is a pasture for gazelles and a convent for Christian monks, a temple for idols and the pilgrim's Ka'ba, the tables of the Torah and the book of the Quran." Jewish mysticism flowered during this same period with the development of Kabbalah. The Zohar, compiled in 13th-century Spain, presented God's inner life as a dynamic interplay of ten sefirot or divine attributes, flowing from Ein Sof (the Infinite) that transcended all human comprehension. Kabbalists saw creation as a process of divine self-limitation (tzimtzum) that made room for finite existence. They sought to participate in tikkun olam—the repair of a broken world—through contemplative practices and ethical action that would restore cosmic harmony. Christian mysticism took diverse forms across medieval Europe. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) experienced vivid visions of divine wisdom as a feminine presence she called Sapientia. Meister Eckhart (c.1260-1328) taught that beyond the Trinity lies the Godhead (Gottheit), an absolute unity that transcends all distinctions: "The eye with which I see God is the same eye with which God sees me." The anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing instructed seekers to approach God through "unknowing" rather than intellectual concepts: "By love he may be gotten and holden, but by thought never." These mystical traditions shared several key insights despite their different religious contexts. First, they distinguished between the personal God of revelation and a deeper divine reality that transcended all categories. Second, they emphasized that the ultimate goal was not knowledge about God but transformative union with the divine. Third, they developed "apophatic" or negative theology—defining God by what God is not rather than by positive attributes that inevitably fall short. The mystical approach created tensions within each tradition. Religious authorities sometimes viewed mystics with suspicion, fearing their direct experience might undermine institutional authority or lead to pantheism. Meister Eckhart faced condemnation from the Pope; some Sufi orders were periodically suppressed; and Kabbalistic teachings were restricted to mature students. Yet mysticism also revitalized these traditions, providing spiritual depth that complemented and enriched more conventional religious expressions. By the late medieval period, these mystical traditions had created a sophisticated vocabulary for spiritual experience that continues to influence contemplative practice today. Their insistence that God transcends all human categories offered a corrective to more anthropomorphic conceptions of deity and provided resources for interfaith dialogue based on shared experience rather than doctrinal agreement.

Chapter 6: Reason's Challenge: God in the Age of Enlightenment (1600-1800)

The period between 1600 and 1800 witnessed unprecedented challenges to traditional conceptions of God as the Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment transformed European intellectual life. This era began with the Copernican revolution, which displaced Earth from the center of the cosmos, challenging the medieval worldview where heaven literally existed "above" and humanity occupied a privileged position in creation. When Galileo pointed his telescope at the heavens in 1609, confirming Copernicus's heliocentric theory, he initiated a scientific approach that would increasingly explain natural phenomena without reference to divine action. Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica (1687) presented a universe operating according to mathematical laws, suggesting a divine "clockmaker" who had designed the cosmic mechanism but perhaps no longer intervened in its operation. Newton himself remained deeply religious, even mystical, but his work provided tools that others would use to develop more mechanistic conceptions of reality. The French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace, when asked by Napoleon about God's place in his celestial mechanics, famously replied: "I had no need of that hypothesis." Philosophers like René Descartes attempted to place religious belief on rational foundations. In his Meditations (1641), Descartes sought to prove God's existence through reason alone, arguing that the idea of a perfect being could only have been placed in the human mind by such a being. Baruch Spinoza took a more radical approach in his Ethics (1677), identifying God with nature itself—"Deus sive Natura" (God or Nature)—a position that led to his excommunication from the Jewish community and condemnation by Christian authorities as an atheist, though he considered himself deeply religious. The Enlightenment proper, emerging in the early 18th century, further transformed religious thought. In England, John Locke advocated religious toleration and a "reasonable Christianity" stripped of mysterious doctrines. Across the Channel, Voltaire attacked religious superstition and intolerance while maintaining a deistic belief in a creator who had established moral law. David Hume's Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (published posthumously in 1779) offered a devastating critique of traditional arguments for God's existence while leaving open the possibility of a minimal deism. These intellectual developments coincided with significant social and political changes. The Peace of Westphalia (1648) ended the devastating Thirty Years' War, fought largely over religious differences, and established principles that began to separate religious identity from political authority. The American and French Revolutions later in the 18th century further advanced the separation of church and state, though in very different ways—the American model protecting religious freedom while the French Revolution initially took a more aggressively secularizing approach. Religious responses to these challenges varied widely. Some theologians embraced aspects of Enlightenment thought, developing "natural religion" that emphasized moral teachings over supernatural claims. Others, like Blaise Pascal, insisted that "the heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of," arguing that religious truth must be apprehended through more than rational analysis. Pietism in Germany and Methodism in England emphasized personal religious experience over doctrinal formulations, while Jewish thinkers like Moses Mendelssohn sought to reconcile traditional faith with modern philosophy. By 1800, the Western religious landscape had been permanently altered. The unified Christian culture of medieval Europe had given way to a more pluralistic environment where multiple interpretations of God competed in the marketplace of ideas. The stage was set for the further diversification of religious thought in the modern era, as believers would continue to wrestle with the challenges posed by scientific advancement, historical criticism, and philosophical skepticism. Yet rather than simply eliminating religious belief, these challenges prompted creative theological responses that continue to influence religious thought today.

Chapter 7: Modern Reconsiderations: Faith After Darwin and Auschwitz (1859-Present)

The modern period has witnessed unprecedented challenges to traditional conceptions of God, yet also remarkable adaptations and reinterpretations of religious thought. Two watershed moments stand out as particularly transformative: Darwin's publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859, which revolutionized understanding of human origins, and the Holocaust (1939-1945), which forced profound theological reconsideration of divine goodness and power in the face of radical evil. Darwin's theory of evolution catalyzed a profound crisis for many believers. By providing a naturalistic explanation for the development of species, evolution seemed to eliminate the need for divine design in nature. Some religious communities responded with rejection, developing what would later be called "creationism." Others found ways to integrate evolutionary understanding with faith. The Jesuit paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) envisioned evolution as God's method of creation, culminating in the "Omega Point" where material and spiritual reality would achieve perfect unity. Process theology, developed by Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne, similarly reimagined God as intimately involved in the world's ongoing development rather than as an unchanging, impassive deity. Historical criticism of sacred texts presented another challenge. Scholars demonstrated that the Bible had been composed from multiple sources over centuries, not written all at once by traditional authors. This undermined literal readings but opened new possibilities for understanding scripture as a record of humanity's evolving relationship with the divine. Reform Judaism, liberal Protestantism, and modernist Catholic scholars embraced these insights, while more conservative branches developed sophisticated responses that maintained traditional authority while acknowledging historical context. The Holocaust forced an even more radical theological reckoning. How could an all-powerful, loving God permit such suffering? Jewish theologian Richard Rubenstein declared that the God of history had died in Auschwitz, while Elie Wiesel's memoir Night described witnessing a young boy's execution and hearing someone ask: "Where is God now?" The answer came: "He is hanging here on this gallows." Christian theologians like Jürgen Moltmann developed a "theology of the cross" emphasizing God's solidarity with human suffering rather than detached omnipotence. The growing awareness of religious pluralism prompted new theological approaches. Some thinkers, including John Hick and Raimon Panikkar, developed "pluralist" theologies suggesting that different religions might be valid responses to the same ultimate reality. Others maintained the uniqueness of their tradition while acknowledging truth in others. The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) marked a watershed in Catholic attitudes toward other religions, acknowledging that salvation was possible outside the Church and encouraging respectful dialogue. Feminist theology emerged as a powerful force in the late 20th century, with thinkers like Mary Daly, Rosemary Radford Ruether, and Judith Plaskow challenging the masculine imagery and patriarchal structures that had dominated religious thought. They recovered forgotten feminine aspects of the divine from religious traditions and developed new language and rituals that spoke to women's experience. Similar work occurred in Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu contexts, transforming understanding of the divine across traditions. The environmental crisis prompted reconsideration of divine relationship to the natural world. Theologians like Sallie McFague proposed models of the world as God's body, challenging traditional dualism between creator and creation. Indigenous religious perspectives gained new attention for their integrated understanding of divine presence within natural systems. Pope Francis's encyclical Laudato Si' (2015) represented a significant shift in Catholic theology toward ecological consciousness. By the early 21st century, the concept of God had become remarkably diverse even within individual religious traditions. Some believers maintained traditional understandings, others embraced process, liberation, feminist, or ecological theologies, while still others adopted more mystical or non-dualistic approaches influenced by Eastern traditions. Rather than a single linear evolution, modern conceptions of God represent a complex ecosystem of thought responding to unprecedented challenges while drawing on ancient wisdom.

Summary

The 4,000-year journey of monotheism reveals a profound pattern: our conceptions of the divine have consistently evolved alongside human consciousness itself. From tribal deities bound to specific territories, through the universal God of the prophets, to the philosophical abstractions of theologians and the intimate presence sought by mystics, each transformation has reflected humanity's expanding understanding of itself and its place in the cosmos. This evolution has never been linear or uniform—different communities have emphasized different aspects of divinity, and older conceptions have persisted alongside newer ones. Yet the overall trajectory shows a remarkable expansion from the particular to the universal, from the external to the internal, from power to compassion. This historical perspective offers valuable insights for navigating our contemporary religious landscape. It suggests that the current challenges to traditional theism—from science, pluralism, and changing social values—are not unprecedented but part of an ongoing process of adaptation and renewal. Rather than seeing modern doubts as threats to religion, we might view them as catalysts for deeper understanding. The history of monotheism demonstrates that periods of crisis have often produced the most creative theological innovations. Perhaps the most enduring lesson is that conceptions of God are not static truths to be defended but living symbols that evolve as human consciousness evolves—pointing always beyond themselves to a reality that transcends our full comprehension but continues to inspire our search for meaning, justice, and connection in an ever-changing world.

Best Quote

“The only way to show a true respect for God is to act morally while ignoring God’s existence.” ― Karen Armstrong, A History of God: The 4000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam

Review Summary

Strengths: The reviewer appreciates the in-depth exploration of the evolution of the concept of God in Christianity and Judaism in the book. The reviewer also notes gaining a better understanding of the origins of Islam. Weaknesses: The reviewer finds the book dense, repetitive, and challenging to follow due to the lack of structure like sections or headings. The length of chapters and paragraphs is also mentioned as a drawback. Overall: The reviewer struggled with the book's dense and esoteric prose, especially when lacking prior knowledge of Islam. Despite gaining insights into Christianity and Judaism, the challenging writing style may not be suitable for readers seeking a more accessible exploration of the subject matter.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.