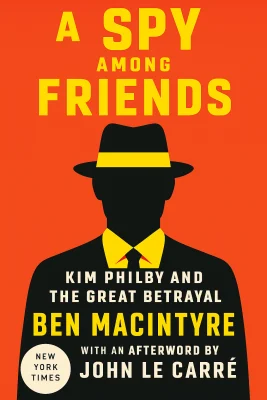

A Spy Among Friends

Philby and the Great Betrayal

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Politics, Audiobook, Biography Memoir, Historical, Russia, War, Espionage

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2014

Publisher

Crown Publishers

Language

English

ASIN

0804136637

ISBN

0804136637

ISBN13

9780804136631

File Download

PDF | EPUB

A Spy Among Friends Plot Summary

Introduction

In a dimly lit apartment in Beirut, January 1963, two middle-aged Englishmen sit across from each other, sipping tea and engaging in what appears to be a cordial conversation. But beneath the veneer of politeness lies a deadly duel of wits. Nicholas Elliott and Kim Philby, once the closest of friends and colleagues in British intelligence, are now locked in a final confrontation. For nearly thirty years, Philby had been living a double life - rising to the highest echelons of MI6 while secretly working as a Soviet spy. Their meeting represents the culmination of one of history's most remarkable tales of friendship, deception, and betrayal. The Kim Philby affair stands as perhaps the most devastating espionage case of the Cold War, a story that transcends mere intelligence history to explore fundamental questions about loyalty, friendship, and identity. Through the intertwined lives of these two men, we witness how the ideological battles of the 20th century played out in the most personal of ways. This isn't simply a spy story, but a profound human drama that reveals how the bonds of class, education, and friendship can both blind us to betrayal and, ultimately, make that betrayal all the more devastating. Whether you're fascinated by espionage history, Cold War politics, or the psychology of deception, this remarkable true story offers insights into how personal relationships can become entangled with the great geopolitical struggles of an era.

Chapter 1: Cambridge Idealism: The Making of a Soviet Spy (1930s)

The story begins in the privileged corridors of Cambridge University in the mid-1930s, where the seeds of one of history's most consequential betrayals were planted. This was a time when Europe was sliding toward catastrophe, with fascism on the rise and ideological battles raging across the continent. For many bright young Cambridge students, including Kim Philby, these political currents created a vortex of radical ideas and commitments that would shape their lives forever. Philby arrived at Cambridge as a history scholar in 1929, the son of St. John Philby, a noted Arab scholar and explorer. While his upper-class background and education marked him as a member of Britain's establishment, Philby was drawn to leftist politics during his university years. The economic depression, the rise of fascism in Europe, and the perceived failures of capitalism led many Cambridge intellectuals toward communism. By 1934, Philby had become convinced that his "life must be devoted to communism," though he wore these convictions so lightly they were nearly invisible to others. The critical moment came when Philby was recruited by Soviet intelligence through Arnold Deutsch, a charismatic NKVD officer operating in London. Deutsch, impressed by Philby's background and potential, gave him the affectionate codename "Sonny" and outlined a vision for his future: Philby would break off all communist contacts, establish a new political image as a right-winger, and penetrate the British establishment. "By background, education, appearance and manners you are an intellectual, a bourgeois," Deutsch told him. "The anti-fascist movement needs people who can enter into the bourgeoisie." Hidden inside the establishment, Philby could aid the revolution in a "real and palpable way." Meanwhile, Nicholas Elliott, another Cambridge graduate and son of the headmaster of Eton, was following a more conventional path into the British establishment. In 1939, through the "Old Boy network" that defined British power structures, Elliott was recruited into MI6, Britain's foreign intelligence service. The contrast between the two men was striking: Elliott, the patriotic Englishman serving his country openly, and Philby, the ideological convert living a carefully constructed double life. Their paths would soon cross, setting in motion a relationship that would last decades and end in one of the Cold War's most dramatic confrontations. The Cambridge years thus witnessed the birth of what would become known as the "Cambridge Spy Ring," with Philby at its center. This period demonstrates how the ideological ferment of the 1930s, combined with the closed networks of the British elite, created perfect conditions for Soviet intelligence to recruit agents who could penetrate the highest levels of British power. The consequences would reverberate through the coming decades, affecting not just Anglo-Soviet relations but the entire landscape of the Cold War.

Chapter 2: Infiltrating the Establishment: Wartime Intelligence (1939-1945)

As Britain plunged into World War II, Kim Philby and Nicholas Elliott found themselves drawn into the shadowy world of wartime intelligence. Their paths converged in 1940 when both joined Section V of MI6, the division devoted to counter-intelligence. Elliott had been recruited through his father's connections, while Philby had maneuvered his way in with the help of influential acquaintances, including Guy Burgess, another Soviet agent. For Philby, this was the culmination of years of patient positioning; as he later wrote, "I had been told in pressing terms by my Soviet friends that my first priority must be the British secret service." The war years saw both men rise rapidly through the ranks. Philby was appointed head of the Iberian section of Section V, responsible for countering German intelligence operations in Spain and Portugal. Elliott was assigned to the Netherlands section before being posted to Istanbul in 1942. Both displayed remarkable aptitude for intelligence work, though their motivations could not have been more different. Elliott was driven by patriotism and a genuine hatred of Nazism, while Philby was systematically betraying British operations to his Soviet handlers. What made Philby's deception so effective was his extraordinary talent for friendship and charm. He cultivated close relationships with colleagues, including Elliott, who later wrote that Philby "had an ability to inspire loyalty and affection." The two men became part of a tight-knit community of intelligence officers who worked together, drank together, and shared secrets that could not be discussed outside their circle. This camaraderie created a perfect cover for Philby's espionage, as no one suspected betrayal from someone so embedded in their social and professional world. Throughout the war, Philby passed volumes of sensitive information to Moscow, including details of British intelligence operations, the identities of agents, and even the structure of MI6 itself. His reports were meticulously detailed, describing his colleagues with waspish precision. Elliott was characterized as "24, 5ft 9in. Brown hair, prominent lips, black glasses, ugly and rather pig-like to look at. Good brain, good sense of humour." Meanwhile, Elliott was unwittingly helping Philby's cause through his own successful operations, most notably the extraction of German defector Erich Vermehren from Turkey in 1944, which yielded valuable intelligence that Philby promptly shared with Moscow. By the war's end, both men had established impressive reputations within British intelligence. Elliott had proven himself in the field, while Philby was increasingly seen as a future leader of MI6. The stage was set for the Cold War, where their relationship would take on new dimensions as former allies became enemies. The war years had demonstrated how effectively Soviet intelligence could penetrate Western institutions through agents who perfectly embodied the values and manners of the British establishment, creating a vulnerability that would have profound consequences in the coming decades.

Chapter 3: Washington Station: Compromising Western Secrets (1949-1951)

In September 1949, Kim Philby arrived in Washington DC to take up what was arguably the most sensitive post in British intelligence - MI6's liaison officer to American intelligence agencies. This appointment represented the ultimate vote of confidence from his superiors and placed him at the very nexus of Anglo-American intelligence cooperation just as the Cold War was intensifying. Ironically, it was James Jesus Angleton, the future CIA counter-intelligence chief who would later become obsessed with Soviet penetration, who had personally recommended Philby for the position. Philby's Washington posting gave him unprecedented access to American intelligence operations. He established particularly close relationships with senior CIA and FBI officials, most notably Angleton, with whom he began to lunch regularly at Harvey's restaurant on Connecticut Avenue. These long, alcohol-fueled lunches became a ritual, beginning with bourbon on the rocks, proceeding through lobster and wine, and ending with brandy and cigars. During these sessions, Angleton shared the most sensitive details of American intelligence operations, including covert actions against the Soviet Union, the CIA's recruitment of former Nazi intelligence officers, and plans for insurgencies in Eastern Europe. The most catastrophic consequence of Philby's betrayal during this period was the failure of Operation Valuable, a joint British-American attempt to foment rebellion in communist Albania. As the liaison officer coordinating between MI6 and the CIA, Philby had complete knowledge of the operation, including the timing and locations of agent infiltrations. He passed this information to Moscow, which shared it with Albanian authorities. The result was a bloodbath - wave after wave of Albanian émigrés, trained and equipped by the West, were captured or killed immediately upon entering the country. "I was responsible for the deaths of a considerable number of Albanians," Philby later admitted without remorse. Meanwhile, Philby's personal life was growing increasingly chaotic. His wife Aileen was suffering from serious mental health issues, and in early 1951, his old friend and fellow Soviet agent Guy Burgess arrived in Washington to take up a post at the British Embassy. Burgess moved into the Philby home and proceeded to scandalize Washington with his outrageous behavior, heavy drinking, and indiscreet comments. This personal drama would soon intersect with a developing crisis in the espionage world. The Venona project, a top-secret American program that had begun decrypting Soviet intelligence communications, was closing in on Donald Maclean, another member of the Cambridge spy ring who had served in the British Embassy in Washington. As the net tightened around Maclean, Philby realized that his own position was increasingly precarious. The Washington years thus ended in crisis, with Philby orchestrating one of the most dramatic episodes in Cold War espionage - the escape of Burgess and Maclean to Moscow in May 1951, an event that would finally cast suspicion on Philby himself and begin the unraveling of his carefully constructed double life.

Chapter 4: Under Suspicion: The Defections and Investigations (1951-1955)

The defection of Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean to the Soviet Union in May 1951 sent shockwaves through Western intelligence communities and cast the first serious shadow of suspicion over Kim Philby. The timing could not have been worse for Philby - he had been preparing to return to London for consultations when Burgess, who had been living in his Washington home, suddenly disappeared along with Maclean. Given Philby's close association with Burgess, questions immediately arose about his possible involvement in the defection. Philby was recalled to London in June 1951 and subjected to intensive interrogation. Though he maintained his innocence, his career in MI6 was effectively over. He was forced to resign in July, ostensibly on the grounds that his friendship with Burgess had shown poor judgment. The official position was that there was "no evidence" against Philby, but privately, suspicions ran deep. MI5 officer Dick White was convinced of Philby's guilt, remarking that "Philby is or has been a Soviet agent," while CIA counter-intelligence chief James Angleton, once Philby's close friend, now began to suspect that he had been deceived by a master spy. For the next four years, Philby lived in a kind of limbo. Outwardly maintaining his innocence, he took work as a journalist, first with a small publication called the Observer Foreign News Service and later as a correspondent for The Economist and The Times in the Middle East. Behind this facade of normalcy, however, his life was disintegrating. His wife Aileen's mental health continued to deteriorate, exacerbated by the stress of the public scandal and her growing conviction that her husband was indeed a Soviet agent. Their marriage collapsed, and Aileen died in 1957 under mysterious circumstances. The pressure on Philby intensified in 1955 when Foreign Secretary Harold Macmillan made a statement in Parliament that effectively named Philby as the "Third Man" who had tipped off Burgess and Maclean. This public accusation prompted Philby to hold a press conference in his mother's apartment, where he calmly denied all allegations. "The last time I spoke to a communist knowing him to be such was in 1934," he declared with characteristic sangfroid. Many found his performance convincing, including some former colleagues who continued to defend him. Throughout this period, Nicholas Elliott remained one of Philby's staunchest supporters. Despite growing evidence of Philby's treachery, Elliott refused to believe that his friend could be a traitor. This loyalty was a testament to the power of the bonds formed within the closed world of British intelligence, where shared background, education, and class created a sense of implicit trust that could override even the most compelling evidence. Elliott's faith in Philby would eventually be shattered, but not before years of continued deception that allowed Philby to evade final exposure and punishment. The period from 1951 to 1955 represents a critical phase in the Philby affair, demonstrating how personal relationships, institutional loyalty, and the reluctance to accept betrayal from within allowed a Soviet agent to weather a storm of suspicion that should have ended his career as a spy. It also highlights the deep damage inflicted on Western intelligence by the Cambridge spy ring, not just in terms of compromised operations but in the atmosphere of paranoia and distrust that would pervade Anglo-American intelligence relations for decades to come.

Chapter 5: The Beirut Confrontation: Elliott's Final Mission (1963)

By January 1963, the elaborate dance of deception between Kim Philby and British intelligence had reached its final act. Philby had been living in Beirut since 1956, working as a correspondent for The Observer and The Economist while secretly continuing his espionage for the Soviet Union. Despite the cloud of suspicion that had hung over him since the Burgess-Maclean defection, he had managed to maintain a façade of innocence, even rebuilding some of his old relationships with former intelligence colleagues. The breakthrough came when new evidence emerged from a Soviet defector, Anatoliy Golitsyn, who provided information that conclusively identified Philby as a long-term Soviet agent. MI6 decided to send Nicholas Elliott, now a senior officer and still technically Philby's friend, to Beirut to confront him and secure a confession. It was a mission fraught with personal and professional significance for Elliott, who had defended Philby for years against accusations of treachery. Now he would be the one to extract the truth from the man who had betrayed both his country and their friendship. The confrontation took place in Philby's apartment in the Christian Quarter of Beirut. Elliott had wired the apartment with a hidden microphone, hoping to record Philby's confession. What followed was an extraordinary exchange between two old friends, now on opposite sides of the Cold War. Elliott presented Philby with the evidence against him, and to his surprise, Philby admitted his espionage, though he attempted to minimize its extent and impact. "I rather thought it would be you," Philby reportedly said when Elliott revealed the purpose of his visit. Over the course of several meetings, Elliott extracted a partial confession, offering Philby immunity from prosecution in exchange for full cooperation. The plan was not to bring Philby back to face justice, but to turn him into a double agent who could feed disinformation to Moscow. Whether this was ever a serious possibility or merely a ruse to keep Philby in place while arrangements were made for his return to Britain remains debated. What is clear is that Philby had no intention of returning to face his former colleagues. On January 23, 1963, Philby disappeared from Beirut. He had boarded a Soviet freighter, the Dolmatova, and defected to Moscow, where he would spend the remaining twenty-five years of his life. Elliott's mission had failed in its ultimate objective - Philby had escaped justice in Britain. Yet it had succeeded in forcing a confession that finally confirmed what many had long suspected: one of Britain's most trusted intelligence officers had been a Soviet agent for nearly thirty years. The Beirut confrontation represents the culmination of a personal drama that had played out against the backdrop of the Cold War. It was the moment when Elliott finally had to face the truth about the man he had admired and defended for so long. The meeting between these two men - one who had lived by the traditional code of British loyalty, the other who had subverted that code in service to a foreign ideology - encapsulates the central human tragedy of the Philby affair: the betrayal not just of country, but of friendship.

Chapter 6: Moscow Exile: Legacy of the Perfect Spy (1963-1988)

Philby's defection to Moscow in January 1963 sent aftershocks through Western intelligence communities that would reverberate for decades. In Britain, the confirmation that one of MI6's most trusted officers had been a Soviet agent for nearly thirty years prompted a painful reassessment of recruitment practices, security procedures, and the culture of trust that had allowed Philby to operate undetected for so long. The damage was incalculable - countless operations compromised, agents betrayed, and lives lost. Perhaps most devastating was the psychological impact on the intelligence services, where suspicion now replaced the clubby atmosphere of mutual trust. For Nicholas Elliott, the betrayal was deeply personal. The man he had defended against accusations, the friend with whom he had shared professional secrets and personal confidences, had been deceiving him all along. Elliott would later describe his confrontation with Philby in Beirut as "one of the most terrible encounters of my life." Yet he continued his career in MI6, eventually rising to a senior position before retiring in 1969. The experience left him with a more nuanced understanding of loyalty and betrayal, though he rarely spoke publicly about Philby until after the spy's death. In Moscow, Philby's reception was initially warm, but reality soon set in. He was awarded the rank of KGB colonel and given a comfortable apartment, but he was never fully trusted by his Soviet handlers, who suspected he might be a triple agent. Isolated from the culture and society he understood, separated from his children, and denied meaningful work, Philby sank into alcoholism and depression. His fourth marriage, to Rufina Pukhova, brought some stability to his later years, but he remained a man between worlds - neither fully accepted by his Soviet masters nor able to return to the country he had betrayed. James Jesus Angleton, once Philby's close friend and admirer, was perhaps the most profoundly affected by the betrayal. As CIA counter-intelligence chief, Angleton launched a relentless hunt for Soviet moles that created a paranoid atmosphere within American intelligence. His "molehunt" led to the investigation of numerous innocent officers and paralyzed CIA operations against the Soviet bloc for years. Angleton's obsession with finding more "Philbys" ultimately led to his forced resignation in 1974, a victim of the very suspicion that Philby's treachery had sown. Philby died in Moscow in 1988, just as the Cold War was drawing to a close. His legacy is complex and contested. To some, particularly in Russia, he remains a hero who followed his ideological convictions at great personal risk. To others, he represents the ultimate betrayal of trust and friendship in service to a totalitarian regime. What is undeniable is the profound impact of his actions on the intelligence landscape of the Cold War, and the human cost of his deception to those who trusted him. The Philby affair ultimately transcends espionage history to become a study in the psychology of deception and the nature of loyalty. It reveals how shared background, education, and social class can create bonds of trust that override objective evidence, and how these same factors can blind institutions to betrayal from within. In an era of renewed great power competition and espionage, the lessons of the Philby affair remain as relevant today as they were during the Cold War.

Summary

The Cold War espionage saga reveals a fundamental truth about intelligence operations: they are, at their core, human endeavors shaped by personal relationships, psychological vulnerabilities, and moral choices. The central paradox that emerges is how the very qualities that make someone trustworthy in the eyes of their colleagues – charm, apparent loyalty, shared background, and personal warmth – can be weaponized by a skilled deceiver. Throughout this history, we see how institutional cultures and personal friendships created blind spots that allowed betrayal to flourish undetected for decades, demonstrating that the most dangerous threats often come not from obvious enemies but from trusted insiders. This history offers profound lessons for contemporary security challenges. First, it cautions against allowing personal relationships or institutional loyalties to override objective assessment of evidence – the "club mentality" that protected the spy for years has modern equivalents in many organizations. Second, it demonstrates the enduring power of ideological conviction as a motivation for betrayal, a factor that remains relevant in today's polarized political landscape. Finally, it reminds us that security systems are ultimately only as strong as the humans who operate them. No amount of technological surveillance or procedural safeguards can fully protect against a trusted insider who has decided to betray. The most effective defense lies in creating institutional cultures where loyalty to shared values is stronger than any external ideology or personal grievance – a lesson as relevant in today's cyber-threatened world as it was during the shadowy intelligence battles of the Cold War.

Best Quote

“Eccentricity is one of those English traits that look like frailty but mask a concealed strength; individuality disguised as oddity.” ― Ben Macintyre, A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal

Review Summary

Strengths: The book is described as well-researched and well-written, providing a thorough biography of Kim Philby. It effectively captures Philby's charisma, intelligence, and the role of his charm and good looks in evading suspicion.\nWeaknesses: The review suggests that the book may not sufficiently address the impact of Philby's actions on the many people who were killed as a result of his betrayal.\nOverall Sentiment: Mixed. While the book is praised for its research and writing quality, there is a critical undertone regarding its treatment of the consequences of Philby's actions.\nKey Takeaway: The book offers a detailed and engaging portrayal of Kim Philby, emphasizing his personal attributes and betrayal, but potentially underemphasizes the human cost of his espionage activities.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.