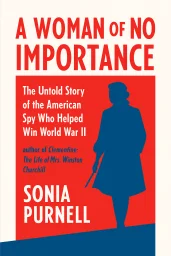

A Woman of No Importance

The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Audiobook, Biography Memoir, Book Club, Historical, World War II, War, Espionage

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2019

Publisher

Viking

Language

English

ASIN

073522529X

ISBN

073522529X

ISBN13

9780735225299

File Download

PDF | EPUB

A Woman of No Importance Plot Summary

Introduction

In the darkest days of Nazi-occupied France, an unlikely hero emerged whose courage and ingenuity would help change the course of World War II. Virginia Hall, an American woman with a wooden leg, became one of the most effective and feared Allied spies, orchestrating resistance networks that sabotaged German operations and saved countless lives. Known to the Gestapo as "the limping lady," she was so successful that Klaus Barbie, the infamous "Butcher of Lyon," declared her "the most dangerous of all Allied spies" and ordered his men to find and destroy her at any cost. Yet despite having her face plastered on wanted posters throughout France, Virginia evaded capture through disguise, cunning, and sheer determination. Virginia's extraordinary story reveals not just the remarkable impact one individual can have in the face of tyranny, but also how limitations can become strengths in the right circumstances. Rejected from the diplomatic service because of her disability, she found her true calling in the shadows of espionage, where her wooden leg—which she affectionately named "Cuthbert"—became part of her legend rather than an impediment. Through Virginia's journey, we witness both the brutal realities of resistance work and the triumph of human resilience. Her life offers profound insights into the nature of courage, the power of determination, and how conventional expectations about gender and disability can be utterly shattered by those who refuse to accept artificial limitations.

Chapter 1: Defying Expectations: The Making of a Spy

Virginia Hall was born in 1906 to a wealthy Baltimore banking family with all the privileges and expectations that accompanied such a position. Her mother, Barbara, had conventional aspirations for her daughter—a suitable marriage, social prominence, and a life befitting their status. Virginia, however, had different ideas from the start. Even as a young girl, she displayed the independence and adventurous spirit that would define her life. While other young women of her social circle focused on social graces and finding suitable husbands, Virginia preferred hunting, horseback riding, and outdoor adventures. Her yearbook from Roland Park Country School captured her essence perfectly when she chose as her motto: "I must have liberty, withal as large a charter as I please." Her education reflected both her family's means and her own intellectual curiosity. Virginia studied at prestigious institutions including Radcliffe and Barnard College, though she was more interested in experience than academic achievement. Her passion for languages and international affairs led her to study in Paris and Vienna during the vibrant 1920s, where she became fluent in French, German, and Italian. These years in Europe shaped her worldview profoundly, exposing her to different cultures and political realities as the continent moved toward the catastrophe of fascism and world war. She developed a particular love for France that would later motivate her most dangerous missions. Despite her excellent qualifications, Virginia's attempts to enter the U.S. diplomatic service were repeatedly thwarted. The State Department of the 1930s was overwhelmingly male and resistant to female diplomats. Nevertheless, she persisted, eventually securing a position as a consular clerk in Warsaw in 1931, followed by assignments in Turkey, Italy, and Estonia. These positions fell far short of her diplomatic ambitions, but they provided valuable experience in international affairs and government operations. More importantly, they positioned her in Europe as the continent descended into darkness, allowing her to witness firsthand the rising threat of fascism. Virginia's path to espionage began with personal tragedy. In December 1933, while hunting in Turkey, her shotgun accidentally discharged, severely wounding her left leg. Gangrene set in, forcing doctors to amputate below the knee. At age 27, Virginia faced a devastating setback that might have broken a less determined spirit. Instead, she approached her recovery with remarkable resilience, learning to walk again with a wooden prosthetic she nicknamed "Cuthbert." When she returned to her consular duties, she refused special accommodations, determined to prove that her disability would not define or limit her. The outbreak of World War II in 1939 found Virginia in Estonia, where she resigned from the State Department after being denied advancement to diplomatic status—her disability now providing officials with a convenient excuse to block her career. When France fell to Nazi Germany in 1940, Virginia volunteered as an ambulance driver for the French Army, demonstrating both her love for her adopted country and her refusal to be sidelined by her disability. As France collapsed under German occupation, Virginia escaped to London, where her unusual combination of skills, knowledge of France, and fierce determination caught the attention of British intelligence. The very disability that had closed doors at the State Department now became an asset in the clandestine world of espionage. By 1941, Virginia had found her true calling as one of the first agents recruited by the newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE), created by Winston Churchill to "set Europe ablaze" through sabotage and subversion. Her first mission would take her into occupied France—a journey into danger that would test her courage, ingenuity, and resilience beyond anything she had previously experienced. The diplomatic career she had been denied was replaced by something far more vital: a chance to strike directly at tyranny from the shadows.

Chapter 2: Turning Point: The Accident That Shaped Her Destiny

The hunting accident that cost Virginia Hall her left leg in 1933 might have ended her dreams of an international career. Instead, it became the catalyst that ultimately led her to her extraordinary wartime role. While on a hunting expedition in the marshlands near Izmir, Turkey, Virginia's shotgun discharged accidentally when she stumbled while climbing over a fence. The blast tore through her left foot, causing catastrophic damage. By the time she reached medical care, gangrene had set in, forcing doctors to amputate her leg below the knee to save her life. At just 27 years old, Virginia faced a future very different from the one she had imagined. The physical and psychological challenges of her recovery were immense. In the 1930s, prosthetic technology was primitive by modern standards. Virginia was fitted with a wooden leg that weighed seven pounds, was held in place by uncomfortable leather straps, and caused constant pain and chafing. Learning to walk again required months of painful practice and extraordinary determination. During this dark period, Virginia experienced what she later described as a vision of her late father, who told her that "it was her duty to survive." This moment became a touchstone for her—if she could endure this suffering, she believed she could face anything life might throw at her. Virginia's response to her disability revealed the core of her character. Rather than accepting limitations, she became determined to prove herself capable of everything she had done before. Within months of receiving her prosthetic, she was back at work at the American consulate, insisting on performing all her duties without special accommodation. She even returned to her beloved pastime of hunting, though it now required significantly more effort and caused her considerable pain. She named her wooden leg "Cuthbert," a touch of humor that reflected her refusal to be defined by her disability or to take herself too seriously despite her circumstances. The State Department, however, saw matters differently. When Virginia applied for the diplomatic corps examination in 1937, she was rejected explicitly because of her amputation. An obscure regulation barring those with missing limbs from diplomatic service was cited, effectively ending her hopes for a conventional diplomatic career. This rejection, painful as it was, pushed Virginia toward a different path. When World War II erupted in 1939, she resigned from the State Department and remained in Europe as the continent descended into conflict. The woman deemed unfit for diplomacy would soon prove herself one of the most effective agents in the fight against fascism. When France fell to Nazi Germany in 1940, Virginia volunteered as an ambulance driver for the French Army. As millions of refugees fled the German advance, Virginia drove her ambulance through the chaos, picking up wounded soldiers from battlefields even as German aircraft bombed the convoys around her. This experience was merely an apprenticeship for what was to come. After France's surrender, Virginia made her way to London, where a chance meeting led to her recruitment by the newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE). The British intelligence officers who interviewed her saw beyond her disability to recognize her extraordinary potential as an agent. In a profound irony, the disability that had barred Virginia from diplomatic service became an asset in the world of espionage. SOE recruiters recognized that her wooden leg made her an unlikely suspect for clandestine work—who would imagine that a woman with such a disability could be a dangerous agent? When asked during her training whether she could ride a horse, sail a boat, shoot, scale mountains, ski, or cycle, she answered yes to all, admitting only that she could not run. Her disability was never mentioned in her SOE files—for the first time since her accident, Virginia was not defined by it. Instead, she was valued for her intelligence, courage, and determination—qualities that would make her one of the most effective Allied agents in occupied Europe.

Chapter 3: Behind Enemy Lines: Building the Lyon Network

Virginia Hall arrived in Lyon in October 1941 with a daunting mission: to build a resistance network from scratch in a city under enemy control. Using the cover identity of an American journalist for the New York Post, she established herself at the Hôtel de la Paix and began the dangerous work of identifying potential recruits. Lyon was strategically important—located at the confluence of the Rhône and Saône rivers, it was a major transportation hub and industrial center. Its complex topography, with hills, rivers, and a network of traboules (hidden passageways through buildings), made it ideal for clandestine operations. Virginia quickly recognized these advantages and set about creating what would become one of the most effective resistance networks in France. Her methods of recruitment revealed both her courage and her psychological insight. She frequented cafés and restaurants, carefully observing the locals and identifying those who might be sympathetic to the resistance. She developed an uncanny ability to judge character—essential when a single misplaced trust could mean death. Among her first recruits was Dr. Jean Rousset, a gynecologist who provided medical care to resistance members and whose clinic became a safe house for fugitives. Another key ally was Germaine Guérin, the madam of a high-class brothel whose "girls" gathered intelligence from their German clients. Virginia's network grew to include people from all walks of life—shopkeepers, factory workers, aristocrats, and even sympathetic police officers who provided warnings of German raids. Virginia established sophisticated operational procedures that became models for resistance work. She created a cell structure where members knew only those in their immediate group, limiting the damage if anyone was captured. She developed elaborate codes and signals for meetings, established safe houses throughout the city, and created dead-drop systems for passing messages without direct contact. Her apartment became the nerve center of resistance operations, with a steady stream of couriers bringing intelligence reports and taking away instructions. Despite the constant danger, Virginia maintained meticulous security protocols that kept her network functioning even as other resistance groups were infiltrated and destroyed. One of Virginia's most remarkable achievements was her infiltration of the Vichy police. She identified and recruited an idealistic Corsican officer, Marcel Leccia, and eventually enlisted both his assistant and his boss. This gave her advance warning of raids and allowed her to secure more lenient treatment for any of her agents who were caught. She also established connections with other resistance networks, creating channels for sharing intelligence and coordinating operations across different regions of France. These connections proved vital when she later orchestrated the escape of twelve SOE agents from the Mauzac internment camp—an operation that required precise coordination between multiple resistance groups. The daily reality of Virginia's life in Lyon was one of constant vigilance and danger. Her disability made her recognizable as "la dame qui boite" (the limping lady), so she varied her routes, checked constantly for followers, and frequently altered her appearance. She acquired a French driver's license to avoid taking trains, where security checks were frequent. Her survival became a battle of wits against the Gestapo and Abwehr, who were increasingly determined to find this elusive agent. Despite these pressures, Virginia maintained both her operational effectiveness and her humanity. She formed deep bonds with her resistance fighters, calling the youngest ones her "chouchou" (pets) and worrying about their welfare even in the midst of dangerous operations. By the summer of 1942, Virginia had established herself as the eyes and ears of the Allies across most of southern France. SOE considered her "amazingly successful" and rated her work as "inspired." From a standing start, she had created a network that provided vital intelligence, conducted sabotage operations, and helped dozens of downed Allied airmen escape to Spain. Her Lyon network became the model for resistance operations throughout occupied Europe, demonstrating how a single determined individual could create an effective underground movement even in the heart of enemy territory.

Chapter 4: The Most Wanted Woman in France

By August 1942, Virginia Hall had become the Nazis' most wanted Allied agent in France. Both the Gestapo and the Abwehr were closing in, determined to capture "la dame qui boite" (the limping lady) or "Die Frau die hinkt" (the woman who limps). Under Operation Donar, named after the Germanic god of thunder, the Nazis planned to infiltrate and destroy resistance networks throughout southern France. Lyon was their primary target, and Virginia was at the top of their list. The Gestapo distributed her photograph to police stations, border posts, and railway stations across France with the chilling notation: "Extremely dangerous. She is the most dangerous of all Allied spies. We must find and destroy her." The pressure intensified when Virginia unwittingly trusted Abbé Robert Alesch, a priest who claimed to be a courier for another resistance network. In reality, Alesch was Agent Axel of the Abwehr, who had already betrayed dozens of resistance members. He gained Virginia's trust by delivering what appeared to be valuable intelligence on German coastal defenses—which was actually doctored material provided by his Abwehr handlers. Though Virginia had doubts about Alesch and asked London to check on him, she continued to work with him, providing him with funds and eventually a radio set. This trust would have devastating consequences for her network. The arrests began closing in around Virginia herself. On October 24, 1942, the Gestapo captured Brian Stonehouse, one of her wireless operators. Despite brutal torture, he refused to reveal Virginia's whereabouts, buying her precious time. But the net was tightening. The Gestapo had placed job advertisements in Lyon newspapers, recruiting informants to denounce anyone connected with the Resistance for twenty thousand francs a month. These new recruits spread across the city, specifically instructed to look out for a woman who limped. Virginia moved to a new apartment on rue Garibaldi, hoping its inaccessibility (sixth floor with a broken lift) would reduce unwanted attention. In November 1942, events took a dramatic turn. The Allied landings in North Africa (Operation Torch) prompted Hitler to order the complete occupation of France. German troops poured across the demarcation line, and the Gestapo moved into Lyon in force. Virginia's police protectors could no longer shield her. Klaus Barbie, the notorious "Butcher of Lyon," arrived to take personal charge of hunting down the Resistance. Known for his sadistic torture methods, Barbie had a particular interest in capturing the elusive American spy who had caused so much damage to German operations. With German troops flooding into Lyon and the Gestapo closing in, Virginia faced a desperate situation. Her escape route via Lisbon was now cut off, and she knew that capture meant certain torture and death. She had no choice but to flee immediately, abandoning her carefully laid plans for rescuing prisoners from the Castres camp. With the Spanish border heavily guarded and the Mediterranean coast under surveillance, there was only one possible escape route left—a treacherous journey on foot across the Pyrenees mountains into neutral Spain in the depths of winter. The decision to attempt this crossing revealed Virginia's extraordinary courage and determination. The Pyrenees in winter presented a formidable challenge for anyone, but for a woman with a wooden leg, it seemed almost impossible. The journey would require climbing steep, snow-covered mountain paths, evading border patrols, and enduring freezing temperatures with minimal equipment. Yet Virginia knew she had no alternative. As German forces closed in on Lyon, she slipped away from the city that had been her base for over a year, leaving behind the network she had built with such care and dedication. The most wanted woman in France was about to undertake her most daring escape yet—a journey that would test her physical and mental limits to the breaking point.

Chapter 5: Escape and Return: Crossing Mountains with Cuthbert

Virginia's escape from France in November 1942 was one of the most extraordinary feats of physical endurance of the war. The Pyrenees crossing was challenging in the best of conditions, but in winter, with snow-covered paths and temperatures well below freezing, it was potentially lethal. For Virginia, with her wooden leg, it represented an almost superhuman challenge. Yet she had no choice—to remain in France meant certain capture by the Gestapo. She began her journey in the French border town of Saint-Jean-de-Luz, where she connected with a guide who specialized in helping refugees escape to Spain. Together with several other fugitives, they set out at night, moving slowly through the foothills before beginning the steep ascent into the mountains. The physical ordeal was excruciating. Virginia's prosthetic leg, never designed for such terrain, caused her constant pain. The wooden socket rubbed against her stump, creating open sores that bled into her sock. The leather straps that held "Cuthbert" in place cut into her skin as she navigated the steep, rocky paths. Snow sometimes reached her waist, forcing her to drag her artificial limb through the drifts. At one point during the journey, she sent a radio message to London saying that "Cuthbert is giving me trouble." Not recognizing this as the name of her prosthetic leg, her handlers replied, "If Cuthbert is troublesome, have him eliminated"—a response that gave Virginia a rare moment of amusement during her ordeal. Despite these challenges, Virginia refused to slow the group down or show any sign of weakness. Her guide later recalled his amazement at her determination, saying that she never complained once during the entire journey. When they stopped to rest, she would turn away from the others to adjust her prosthesis or tend to her wounds, unwilling to draw attention to her disability. After three days and nights on the mountain, they finally crossed into Spain, only to be immediately arrested by Spanish border guards. Spain, though officially neutral, was sympathetic to Nazi Germany, and refugees caught entering the country illegally were often returned to France. Virginia and her companions were taken to a prison in Figueres, where they were held in squalid conditions. Using her cover as an American journalist, Virginia managed to smuggle a message to the U.S. consulate in Barcelona. After several anxious weeks, American diplomatic pressure secured her release. She made her way to Madrid and then to London, where she arrived in January 1943. SOE officials were astonished by her escape and her physical resilience. Her crossing of the Pyrenees with a wooden leg became the stuff of legend within the organization. She was awarded the Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for her services, though the decoration remained secret due to the classified nature of her work. Despite the ordeal she had endured, Virginia was determined to return to the field. She lobbied SOE to send her back to France, arguing that her knowledge and experience were too valuable to waste. SOE was reluctant—she was now too well-known to operate safely in her previous areas. Instead, they assigned her to train new agents, sharing her hard-won expertise in fieldcraft and security. But desk work did not satisfy Virginia's burning desire to continue the fight. In March 1944, she found a new path forward through the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA. William Donovan, the head of OSS, recognized her exceptional abilities and recruited her despite SOE's reluctance to release her. Virginia's return to France in March 1944 required a complete transformation. She underwent extensive training in disguise techniques, learning to alter her appearance and movement patterns. She dyed her hair gray, had her teeth filed down to resemble those of a French peasant woman, and learned to walk with a shuffling gait that disguised her limp. She adopted the identity of an elderly farmwoman named Marcelle Montagne and was smuggled back into France via a fishing boat that landed on a remote beach in Brittany. Three months after D-Day, a German officer who had seen Virginia's wanted poster from 1942 encountered an old peasant woman collecting eggs near Cosne. He never suspected that this stooped, gray-haired figure was the spy he had been ordered to capture on sight—a testament to the effectiveness of Virginia's disguise and her extraordinary ability to adapt and survive in the most dangerous circumstances.

Chapter 6: Arming the Resistance: Preparing for D-Day

Virginia Hall's return to France in March 1944 marked the beginning of her most daring and effective period as a resistance organizer. Operating under the code name "Diane," she was parachuted into the Haute-Loire region with a radio operator and instructions to assess the strength of local resistance groups. However, Virginia quickly expanded her mission beyond these limited objectives. She recognized that with the Allied invasion imminent, the time had come to transform the scattered resistance cells into a coordinated fighting force capable of supporting the liberation. Moving into the rural area around Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, Virginia established herself as a peasant woman named Marcelle Montagne. She took a job as a milkmaid on a local farm, which provided perfect cover for her activities. Her primary mission was to arm and organize the Maquis—rural resistance fighters, many of them young men hiding from forced labor in Germany. These groups were eager to fight but lacked weapons, training, and coordination. Virginia set about transforming them into an effective guerrilla force. She arranged for airdrops of weapons, explosives, and supplies, personally supervising the reception committees that collected these vital materials. These operations required precise timing and coordination—marking drop zones with flashlights in specific patterns, recovering containers often weighing hundreds of pounds, and distributing materials while evading German patrols. Between April and August 1944, Virginia coordinated over 30 successful supply drops, providing enough weapons and equipment to arm hundreds of resistance fighters. Virginia's training of the Maquis went beyond simply providing weapons. She taught them guerrilla tactics, sabotage techniques, and basic military discipline. She organized them into structured units with clear chains of command and specific operational responsibilities. She insisted on strict security protocols and compartmentalization of information to protect against infiltration. Most importantly, she gave these often disparate groups a sense of purpose and direction, channeling their anger and patriotism into effective resistance. Under her guidance, they transformed from amateur fighters into a disciplined force capable of coordinated action against German targets. As D-Day approached in June 1944, Virginia received orders to launch a campaign of sabotage to disrupt German reinforcements heading north. Her teams blew up bridges, cut telephone lines, derailed trains, and ambushed German convoys. One of her most successful operations was the destruction of a key railway bridge at Langeac, which prevented German armor from moving north to reinforce Normandy. In another operation, her Maquis fighters ambushed a German convoy near Le Puy, destroying several vehicles and capturing valuable intelligence documents. These actions, replicated by resistance groups across France, created chaos behind enemy lines and prevented thousands of German troops from reaching the Normandy battlefront. Virginia's radio became the lifeline for resistance operations across central France. She transmitted for hours each day, coordinating with London and other agents, despite the constant danger of detection. The Germans had mobile direction-finding units specifically hunting for her signal. She frequently changed locations, often transmitting from barns, caves, or forests to avoid capture. Her radio reports provided Allied commanders with crucial intelligence on German troop movements, defensive positions, and the effectiveness of bombing campaigns. This information helped shape battle plans and target air strikes, making her one of the most valuable intelligence assets in occupied France. By August 1944, as Allied forces pushed eastward across France, Virginia's role evolved once again. She formed a mobile guerrilla unit known as the "Diane Irregulars" to harass retreating German forces. This group of about twenty hand-picked fighters, equipped with captured German vehicles and weapons, conducted hit-and-run attacks on enemy convoys and outposts. Virginia personally led many of these operations, displaying a tactical acumen that impressed even professional military officers. When American forces finally reached her area, they were astonished to discover that this legendary resistance leader, who had organized such effective operations, was both a woman and an amputee. As one American officer reportedly remarked, "She is the only allied woman agent who has ever worked with a successful sabotage group; the value of her work is reflected in the fact that the group was probably the most successful of all those that operated in France."

Chapter 7: Legacy of Courage: Redefining the Possible

Virginia Hall's extraordinary wartime career did not end with the liberation of France. After the war, she joined the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency, becoming one of its first female operations officers. Despite her proven leadership abilities in the field, she faced the same gender discrimination that had thwarted her diplomatic ambitions before the war. Relegated to desk jobs and denied promotions given to less experienced male colleagues, she nevertheless continued to serve with distinction until her retirement in 1966. Throughout her CIA career, she maintained the secrecy that had kept her alive during the war, rarely speaking about her experiences even to family members. When asked about her wartime activities, she would simply say she was "unwilling to talk" about what she did. The full extent of Virginia's contributions only began to emerge after her death in 1982. French Resistance members testified to her pivotal role in organizing and sustaining their operations. SOE records, gradually declassified, revealed the scope of her achievements. The official SOE historian M.R.D. Foot acknowledged that "without her, half of F Section's early operations in France could never have been carried out at all." Her name appears more frequently than any other in SOE's surviving War Diaries. In recognition of her extraordinary service, Virginia received significant honors from three nations: the Distinguished Service Cross from the United States (the only civilian woman to receive this honor during World War II), the Croix de Guerre with Palme from France, and appointment as a Member of the Order of the British Empire from Great Britain. Virginia's legacy extends far beyond her individual accomplishments. She helped pioneer a new role for women in espionage and combat at a time when they were expected to be supportive and secondary. Her success opened the gates for more female agents—SOE would eventually send thirty-nine women into occupied France. As Maurice Buckmaster, head of F Section, noted: "We were destined to be surprised to find that even in jobs originally deemed to be men's prerogatives, they showed great enthusiasm and skill." The methods Virginia helped develop—building networks of resistance, coordinating sabotage, gathering intelligence behind enemy lines—became standard practice for special operations forces. Her understanding of irregular warfare, propaganda, and the formation of an enemy within presaged modern counterinsurgency techniques. Perhaps most remarkably, Virginia achieved all this while overcoming both gender discrimination and physical disability. Her prosthetic leg, which she nicknamed "Cuthbert," caused her constant pain and made even simple movements challenging. Yet she never allowed it to define or limit her. When SOE headquarters radioed asking how Cuthbert was doing during a particularly difficult period, she famously replied: "Cuthbert is giving me trouble, but I can cope." This response encapsulated her approach to all obstacles—acknowledging difficulties but refusing to be defeated by them. In an era when disabilities were often viewed as disqualifying limitations, Virginia demonstrated that determination and courage could overcome even the most significant physical challenges. Virginia Hall's story remained largely unknown during her lifetime, partly due to the classified nature of her work and partly due to her own reticence. In recent years, however, her extraordinary achievements have begun to receive the recognition they deserve. Books, documentaries, and even feature films have brought her story to a wider audience, inspiring a new generation with her courage and determination. In 2019, the CIA named a training facility in her honor, and in 2020, a street in Baltimore was renamed "Virginia Hall Way." These tributes acknowledge not just her wartime heroism but her lasting impact on intelligence operations and women's roles in national security. Today, Virginia Hall stands as a testament to what can be achieved through determination, courage, and resilience in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Her life demonstrates how adversity and rejection can sometimes forge extraordinary strength and resolve. She showed that women could step out of conventional roles to make vital contributions in traditionally male domains. And she proved that physical disabilities need not limit one's impact on the world. In an age that told women, particularly disabled women, what they could not do, Virginia Hall simply refused to listen. Instead, she rewrote the rules, redefining what was possible through sheer force of will and an unwavering commitment to freedom.

Summary

Virginia Hall's extraordinary journey represents one of the most remarkable individual contributions to Allied victory in World War II. From the privileged daughter of a Baltimore banking family to "the most dangerous of all Allied spies," her transformation defied every convention and limitation of her era. What makes her story so powerful is not just what she accomplished but how she accomplished it—turning apparent disadvantages into strategic assets. Her gender, her disability, and her outsider status became tools rather than obstacles in her hands. In an age that told women, particularly disabled women, what they could not do, Virginia Hall simply refused to listen. Her legacy teaches us that courage, intelligence, and determination transcend physical limitations and social expectations. Virginia's life offers profound lessons for anyone facing obstacles or limitations. She demonstrates that setbacks—even devastating ones like losing a limb—can become catalysts for discovering one's true purpose and potential. Her story challenges us to question our assumptions about who can lead, who can fight, and who can change the course of history. For modern intelligence services, her methods of network-building, agent recruitment, and clandestine communication remain relevant models. For individuals facing their own limitations—whether physical, social, or self-imposed—Virginia offers a powerful example of how to redefine what is possible. Her extraordinary courage in the face of tyranny reminds us that even in the darkest times, individuals of exceptional character can make a profound difference in the struggle for freedom and human dignity.

Best Quote

“Valor rarely reaps the dividends it should.” ― Sonia Purnell, A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II

Review Summary

Strengths: The book's content is highly praised, with the story described as "absolutely fascinating" and engaging enough to be a quick read. Weaknesses: The writing is critiqued for being surface-level, lacking depth in character development and tactical details. The narrative is said to move too quickly, glossing over significant events. Additionally, the integration of sources is criticized for being unclear, as they are used as footnotes without proper context in the text. Overall Sentiment: Mixed Key Takeaway: While the book offers a captivating story about Virginia Hall, its execution is hindered by superficial writing and inadequate integration of sources, leaving the reader desiring more depth and clarity.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.