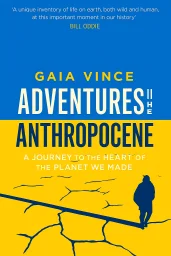

Adventures in the Anthropocene

A Journey to the Heart of the Planet We Made

Categories

Nonfiction, Science, History, Nature, Travel, Sustainability, Geography, Environment, Ecology, Climate Change

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2014

Publisher

Milkweed Editions

Language

English

ISBN13

9781571313577

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Adventures in the Anthropocene Plot Summary

Introduction

Throughout human history, empires have risen and fallen in patterns that reveal deep truths about power, governance, and human nature. From the fertile river valleys of ancient Mesopotamia to the global superpowers of the modern era, these imperial cycles follow recognizable trajectories of emergence, expansion, stabilization, and eventual decline. What causes certain societies to achieve dominance while others remain peripheral? Why do seemingly invincible powers eventually crumble? These questions have fascinated historians for centuries and continue to provide valuable insights for understanding our present world. The study of imperial cycles offers more than just historical curiosity—it provides crucial context for interpreting contemporary geopolitical developments. By examining how past empires managed diversity, responded to environmental challenges, balanced central authority with local governance, and ultimately failed to sustain their dominance, we gain perspective on the challenges facing today's global powers. This historical journey is particularly valuable for policy makers, students of international relations, and anyone seeking to understand how the past shapes our present and might inform our future. The patterns revealed across millennia suggest that while technologies and ideologies change, the fundamental dynamics of power often remain surprisingly constant.

Chapter 1: Cradles of Power: Early River Valley Civilizations (3500-1000 BCE)

The story of imperial cycles begins with the emergence of the first complex civilizations along major river valleys between 3500 and 1000 BCE. In Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Egypt along the Nile, the Indus Valley in South Asia, and China's Yellow River basin, humans first developed the organizational capacity to build states that controlled significant territories and populations. These river valleys provided fertile soil replenished by annual flooding, allowing agricultural surpluses that could support specialized craftspeople, priests, administrators, and soldiers who did not produce their own food. These early civilizations developed remarkably similar innovations despite their geographic separation. Writing systems emerged first as accounting tools but evolved to record laws, religious texts, and literature. Monumental architecture—ziggurats in Mesopotamia, pyramids in Egypt, elaborate city planning in the Indus Valley—demonstrated the ability to mobilize labor on an unprecedented scale. Complex religious systems intertwined with political authority, with rulers often claiming divine sanction or even godhood. Irrigation works requiring collective maintenance necessitated centralized coordination, contributing to the development of bureaucratic systems and formal governance structures. The first true empire emerged in Mesopotamia when Sargon of Akkad (circa 2334-2279 BCE) conquered the independent Sumerian city-states and established a unified administration. His achievement demonstrated how military power could be leveraged to create larger political units, but also revealed the challenges of maintaining control over diverse populations. After Sargon's death, his empire fragmented as local identities reasserted themselves—establishing a pattern of imperial consolidation followed by disintegration that would repeat throughout history. Later Mesopotamian empires, including the Babylonian and Assyrian, would develop more sophisticated techniques of imperial control, including deportation of conquered populations and standardized provincial administration. Environmental factors played crucial roles in these early imperial cycles. The Akkadian Empire's collapse coincided with a severe drought around 2200 BCE that destabilized agricultural production. In the Indus Valley, changing river patterns and possible climate shifts contributed to urban abandonment around 1900 BCE. Egypt's greater environmental stability along the predictable Nile contributed to its remarkable political continuity compared to Mesopotamia's more turbulent imperial succession. These cases established a pattern visible throughout history—environmental challenges often serve as threat multipliers that can accelerate imperial decline when combined with political, economic, or military pressures. The legacy of these early civilizations extended far beyond their timeframes. Their innovations in writing, mathematics, metallurgy, and governance created templates that subsequent empires would build upon. The concept of divinely sanctioned kingship, the development of written legal codes, the use of monumental architecture to project power, and the creation of professional bureaucracies all originated in these river valley societies. When later empires sought to legitimate their rule, they often connected themselves to these ancient precedents—the Persian kings presented themselves as heirs to Mesopotamian traditions, while Roman emperors adopted Egyptian symbols of divine authority. These first experiments in large-scale political organization established patterns of imperial development that would be repeated and refined for millennia to come.

Chapter 2: Classical Empires and Their Administrative Innovations (500 BCE-500 CE)

Between 500 BCE and 500 CE, a new generation of empires emerged that dramatically expanded the scale and sophistication of imperial governance. The Persian Empire under the Achaemenid dynasty created the first truly multicontinental state, spanning from Egypt to the Indus Valley. Alexander the Great's brief but spectacular conquests spread Hellenic culture throughout the Near East. Rome transformed from a small Italian city-state to dominate the entire Mediterranean basin. In Asia, the Han Dynasty unified China while the Mauryan Empire briefly united most of the Indian subcontinent. These classical empires developed administrative systems capable of governing vast territories and diverse populations with unprecedented effectiveness. The Persian Empire pioneered innovations in imperial administration that subsequent empires would adopt and adapt. Under Darius I (522-486 BCE), the empire was divided into standardized provinces (satrapies) governed by appointed officials who collected taxes and maintained order while allowing considerable local autonomy in cultural and religious matters. A royal road system spanning over 1,600 miles facilitated rapid communication, with relay stations providing fresh horses for imperial messengers. This administrative structure allowed the Persians to govern diverse peoples without forcing cultural assimilation—a pragmatic approach that reduced resistance to their rule. As the Greek historian Herodotus noted, the Persians "of all nations most readily adopt foreign customs," incorporating successful practices from conquered peoples rather than imposing their own traditions. Rome developed perhaps history's most successful system of imperial expansion and consolidation. Beginning as a republic governed by elected officials and the Senate, Rome gradually developed mechanisms for incorporating conquered territories—first by extending citizenship to neighboring Italian communities, then by establishing provinces administered by governors sent from the capital. The empire reached its greatest extent under Trajan in the early second century CE, encompassing some 70 million people from Britain to Mesopotamia. Roman law provided a consistent framework for commerce and governance, while an extensive network of roads, bridges, and harbors facilitated trade and military movement. The Romans excelled at co-opting local elites into their system, offering citizenship and opportunities for advancement that gave provincial aristocrats a stake in imperial success. In China, the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) created an imperial system that would influence East Asian governance for two millennia. The emperor ruled through a centralized bureaucracy increasingly staffed by officials selected through competitive examinations testing knowledge of Confucian classics. This meritocratic system created a class of professional administrators loyal to the imperial system rather than to aristocratic lineages. The Han government intervened extensively in the economy, managing grain reserves to stabilize prices, operating monopolies on salt and iron, and constructing irrigation works. Unlike Rome, which generally allowed considerable local autonomy, the Chinese imperial model emphasized direct administrative control extending down to the county level. These classical empires ultimately collapsed due to combinations of internal corruption, economic strain, environmental challenges, and external pressures. Rome's overextension, economic troubles, and Germanic invasions led to the western empire's collapse in 476 CE, though the eastern half survived as the Byzantine Empire. The Han Dynasty faced similar challenges with corruption, peasant rebellions, and nomadic invasions contributing to its dissolution. These parallel collapses demonstrated common vulnerabilities in imperial systems—the difficulty of maintaining administrative quality over time, the challenge of defending extended frontiers, and the tendency for wealth to concentrate in ways that undermined the social cohesion necessary for imperial defense. Despite their political collapse, these classical empires left enduring legacies that shaped subsequent history. Roman law formed the basis for legal systems across Europe and beyond. Confucian governance principles continued to guide Chinese administration through multiple imperial cycles. Persian administrative techniques influenced both Islamic and Byzantine governance. These empires demonstrated that while political structures might fall, cultural and institutional legacies could survive to influence future civilizations in profound ways. Their administrative innovations—professional bureaucracies, standardized provincial governance, extensive infrastructure networks, and mechanisms for incorporating diverse populations—created templates that subsequent empires would adapt to their own circumstances.

Chapter 3: Medieval Fragmentation and Religious Civilizations (500-1450 CE)

The millennium following the collapse of classical empires witnessed a fundamental reorganization of political power across Eurasia and Africa. Rather than unified imperial systems, this period saw the emergence of competing religious civilizations, feudal fragmentation in Europe, and new patterns of long-distance trade that connected previously isolated regions. While often characterized as a "dark age" in Western historical tradition, this era actually featured remarkable cultural efflorescence and institutional innovation across multiple civilizations. In Western Europe, the fall of Rome led to political fragmentation and the rise of feudalism—a decentralized system where power was distributed among kings, nobles, and the Catholic Church. Charlemagne briefly united much of Western Europe around 800 CE, receiving the imperial crown from the Pope, but his Carolingian Empire quickly fragmented after his death. The medieval European political landscape featured competing kingdoms, principalities, church territories, and city-states with overlapping authorities and jurisdictions. This decentralization limited state power but fostered institutional diversity and competition that would eventually contribute to Europe's dynamic development. The Catholic Church provided cultural and institutional unity across political boundaries, maintaining Latin literacy, preserving classical texts, and developing sophisticated legal and administrative systems. The Byzantine Empire continued Roman imperial traditions in the eastern Mediterranean until its final conquest by the Ottomans in 1453. From its capital at Constantinople, Byzantine emperors governed through a sophisticated bureaucracy and maintained the most powerful economy in Europe for centuries. Meanwhile, the Islamic caliphates united the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of South Asia under Muslim rule following the death of Muhammad in 632 CE. The Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates created cosmopolitan civilizations that preserved and expanded upon classical learning during Europe's darkest hours. Baghdad under the Abbasids became the world's most sophisticated center of learning, with scholars translating Greek, Persian, and Indian texts while making original contributions to mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy. In East Asia, the Tang (618-907 CE) and Song (960-1279 CE) dynasties represented a golden age of Chinese civilization, developing technologies like printing, paper money, and gunpowder that would eventually transform the world. China's imperial system recovered after the Han collapse, creating a more commercially oriented society with unprecedented urban growth. The Song capital of Kaifeng may have housed over a million people, making it the world's largest city at the time. In South Asia, the subcontinent remained politically fragmented after the Mauryan and Gupta empires, with regional kingdoms competing for dominance while sharing a common cultural framework influenced by Hinduism, Buddhism, and later, Islam. Trade networks expanded dramatically during this period, connecting previously isolated regions. The Silk Roads linking China to the Mediterranean revived under the Mongol Empire, which briefly united much of Eurasia in the 13th century. Maritime trade across the Indian Ocean connected East Africa, the Middle East, India, Southeast Asia, and China in complex commercial networks dominated by Arab and Persian merchants. Trans-Saharan trade routes linked Mediterranean North Africa with West African kingdoms like Ghana, Mali, and Songhay, which grew wealthy from gold and salt commerce. These networks exchanged not just goods but also technologies, religious ideas, and diseases, creating the first truly global systems of interaction. The medieval period ended with several developments that would reshape global power dynamics. The Mongol conquests of the 13th century facilitated unprecedented cultural and technological exchange across Eurasia. The Black Death pandemic of the 14th century killed perhaps a third of Europe's population, disrupting feudal labor systems and creating opportunities for social mobility. In Europe, the Renaissance began reviving classical learning, while technological innovations in shipbuilding and navigation prepared the way for European overseas expansion. These developments set the stage for the next great transformation in global history—the age of exploration and colonial expansion that would create the first truly global empires and shift the center of global power from Asia to Western Europe.

Chapter 4: Age of Exploration and First Global Empires (1450-1750)

Between 1450 and 1750, European powers launched unprecedented voyages of exploration that connected the world's regions into the first truly global system of trade, conquest, and cultural exchange. This transformation began with Portuguese expeditions along the African coast seeking new routes to Asian markets, culminating in Vasco da Gama's arrival in India in 1498. Christopher Columbus's 1492 voyage to the Americas and Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation of the globe completed by his crew in 1522 revealed the full extent of the world to European knowledge. These journeys were made possible by technological innovations in shipbuilding, navigation, and weaponry, particularly the development of caravels capable of sailing against the wind, improved compasses and astronomical instruments, and more effective naval cannons. The consequences of this global connection were profound and often devastating. In the Americas, European diseases like smallpox decimated indigenous populations who lacked immunity, causing demographic collapse that some historians estimate killed up to 90% of the native population. This biological catastrophe facilitated European conquest and colonization, as Spanish conquistadors like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro overthrew the Aztec and Inca empires with remarkably small forces. European powers established colonial empires through conquest and settlement, with Spain dominating Central and South America, Portugal claiming Brazil, and later, England, France, and the Netherlands establishing colonies in North America and the Caribbean. These empires extracted vast wealth through mining precious metals, plantation agriculture using enslaved labor, and monopolistic trade systems. The transatlantic slave trade emerged as one of this era's most significant and tragic developments. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, approximately 12 million Africans were forcibly transported to the Americas to work on plantations producing sugar, cotton, tobacco, and other commodities. This massive forced migration transformed demographics across the Atlantic world and created enduring systems of racial hierarchy. African societies were destabilized by slave raiding, while European economies and banking systems developed partly through profits from slave-produced goods. The triangular trade linking Europe, Africa, and the Americas became the foundation of the first truly global economic system. In Asia, European expansion took different forms. Unable to conquer powerful states like Ming China or Mughal India through direct military means, Europeans instead established trading posts and gradually expanded their influence through commercial dominance. The Portuguese established a network of fortified outposts from East Africa to Japan. The Dutch East India Company effectively controlled the spice trade from Indonesia, while the English East India Company began transforming from a trading enterprise to a territorial power in the Indian subcontinent. These chartered companies represented a new form of imperial organization, blending commercial and sovereign functions in ways that allowed European states to project power globally with limited direct investment. This period witnessed the emergence of the first global economic system, centered on European imperial powers but incorporating regions worldwide. The "Columbian Exchange" transferred plants, animals, and diseases between hemispheres, transforming diets and agriculture globally. American crops like potatoes, corn, and tomatoes spread worldwide, supporting population growth in Europe and Asia. Silver mined in Spanish America flowed to Europe and then to China, creating the first truly global trade networks. Meanwhile, European powers developed mercantilist economic policies designed to extract wealth from colonies while limiting their economic development and ensuring that trade benefited the imperial center. By 1750, these global connections had transformed societies worldwide and shifted the balance of global power. Western Europe, previously a peripheral region compared to the great civilizations of Asia, had leveraged its maritime technology and military advantages to establish global influence. The foundations were being laid for the next great transformation—the Industrial Revolution—which would further amplify European power and reshape global relationships in even more profound ways. The first global empires demonstrated how technological advantages could be translated into worldwide systems of economic and political dominance, establishing patterns of global inequality that would persist long after formal colonial rule ended.

Chapter 5: Industrial Nation-States and Imperial Competition (1750-1914)

The period from roughly 1750 to 1914 witnessed the most fundamental transformation in human history since the Neolithic Revolution—the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the modern nation-state. Beginning in Great Britain in the late 18th century, industrialization revolutionized manufacturing through technological innovations like the steam engine, mechanized textile production, and later, electricity and internal combustion engines. These changes dramatically increased productive capacity while transforming social structures, urbanization patterns, and eventually, global power relationships. The factory system replaced household production, cities expanded dramatically, and new social classes emerged as traditional agrarian societies were transformed into industrial economies. Industrialization spread unevenly across the globe, creating new patterns of inequality between and within societies. After Britain, industrialization spread to Western Europe and the United States, then gradually to Russia, Japan, and parts of Latin America. This uneven development created a widening gap between industrialized and non-industrialized regions that would fundamentally reshape global power relationships. Within industrializing societies, new social classes emerged—industrial capitalists who owned factories and machinery, and an urban working class (proletariat) who operated them. Working conditions in early factories were often brutal, with long hours, dangerous conditions, and child labor common. These conditions eventually sparked labor movements, socialist ideologies, and demands for political reform that would reshape domestic politics across industrializing nations. The 19th century also saw the consolidation of the modern nation-state as the dominant form of political organization. The French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars spread ideas of nationalism, citizenship, and popular sovereignty across Europe. New nations formed through unification movements (Germany and Italy) or independence struggles (in Latin America and later parts of Eastern Europe). These nation-states developed bureaucratic administrations, national education systems, standardized languages, and conscript armies that dramatically increased state power over society. The combination of industrial capacity and nationalist mobilization created military forces of unprecedented size and capability, shifting the global balance of power decisively toward industrialized nation-states. Imperialism reached its zenith during this period, as industrialized powers used their technological and military advantages to dominate much of Asia and Africa. The "Scramble for Africa" in the late 19th century saw European powers partition nearly the entire continent, while Britain consolidated control over India, and various powers carved spheres of influence in China. This "new imperialism" was driven by economic motivations (markets, raw materials, investment opportunities), strategic competition between European powers, and cultural ideologies of racial superiority and "civilizing missions." By 1914, European powers controlled approximately 84% of the world's land surface, creating the largest imperial systems in human history. New ideologies emerged to interpret and respond to these transformations. Liberalism advocated constitutional government, individual rights, and free markets. Socialism critiqued capitalism's inequalities and called for worker control of production. Nationalism mobilized populations around shared cultural identities, sometimes promoting democratic reforms but also fueling aggressive militarism. Social Darwinism and scientific racism developed pseudo-scientific justifications for imperial domination and racial hierarchies. These competing ideologies would shape political conflicts into the 20th century and beyond, providing frameworks for understanding the dramatic changes transforming societies worldwide. By 1914, industrialization and nation-state formation had transformed global power relationships. Western Europe and the United States achieved unprecedented economic and military power, dominating global trade and politics. Japan demonstrated that non-Western societies could successfully industrialize while maintaining cultural independence, becoming the first non-Western imperial power. However, the competitive dynamics between industrialized nation-states, combined with nationalist rivalries and imperial competition, created tensions that would explode in the catastrophic world wars of the 20th century. The very forces that had created unprecedented prosperity and power—industrial capacity, nationalist mobilization, and imperial competition—would soon produce unprecedented destruction, fundamentally reshaping the global order yet again.

Chapter 6: World Wars and the Reshaping of Global Order (1914-Present)

The period from 1914 to the present has been defined by unprecedented global conflicts, ideological struggles, decolonization, and the emergence of new forms of global integration. The First World War (1914-1918) erupted from a complex web of nationalist rivalries, imperial competition, militarism, and alliance systems among European powers. The conflict introduced industrial-scale warfare with devastating new technologies like machine guns, poison gas, tanks, and aircraft. Over 9 million soldiers died, four empires collapsed (German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian), and the European-dominated international order was fundamentally destabilized. The war's aftermath saw the first attempt to create a global governance system through the League of Nations, though this would prove inadequate to prevent future conflicts. The interwar period (1919-1939) saw failed attempts to rebuild the international system while economic crises and ideological extremism undermined democratic governments. The Great Depression that began in 1929 devastated economies worldwide, discrediting liberal capitalism and fueling the rise of totalitarian regimes. The Soviet Union under Stalin implemented forced industrialization and collectivization at enormous human cost. In Germany, Hitler's Nazi regime combined extreme nationalism, antisemitism, and expansionist ambitions. In Japan, militarists pursued imperial expansion in Asia. These developments set the stage for an even more devastating global conflict. World War II (1939-1945) surpassed even its predecessor in scale and destruction. The conflict spread across Europe, North Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, directly involving more than 30 countries. New technologies like strategic bombing and eventually nuclear weapons targeted civilian populations. The Holocaust represented genocide on an industrial scale, with Nazi Germany systematically murdering six million Jews and millions of others deemed undesirable. Total casualties reached 70-85 million, including unprecedented civilian deaths. The war ended with the United States and Soviet Union emerging as superpowers, while traditional European powers were diminished. The United Nations was established as a more robust attempt at global governance, while the Bretton Woods system created new international economic institutions. The Cold War (1945-1991) restructured international relations around ideological competition between the American-led capitalist bloc and the Soviet-led communist bloc. Direct conflict between superpowers was avoided through nuclear deterrence, but proxy wars erupted in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. Nuclear weapons proliferation created the threat of mutual assured destruction. Within this bipolar framework, former colonies achieved independence through both peaceful transitions and violent struggles. By 1975, most of Asia and Africa had achieved formal independence, though economic dependence often persisted. The Cold War's end with the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991 seemed to mark the triumph of liberal democracy and market capitalism, though this "end of history" proved premature. Globalization accelerated dramatically in the late 20th century, creating new forms of international integration and interdependence. Economic globalization accelerated with reduced trade barriers, multinational corporations, global supply chains, and financial integration. Digital technologies and the internet created unprecedented connectivity. However, globalization also generated new inequalities, cultural tensions, and environmental challenges. Climate change emerged as a global threat requiring unprecedented international cooperation, while pandemics like COVID-19 demonstrated the vulnerabilities created by global interconnection. The early 21st century has been marked by complex and contradictory trends. Democratic governance expanded but faces challenges from populist movements and authoritarian resurgence. Terrorism, civil wars, and refugee crises demonstrate continuing security challenges. Rising powers like China are challenging Western dominance, potentially leading toward a more multipolar world order. These developments suggest that the reshaping of global order that began with the world wars continues today, with the future trajectory of human civilization remaining uncertain. The lessons of past imperial cycles—the dangers of overextension, the importance of legitimate governance, and the inevitability of change—remain relevant as humanity navigates an increasingly interconnected yet divided world.

Summary

Throughout history, empires have followed recognizable patterns of development, expansion, and decline that offer profound insights into the nature of power and governance. They typically emerge when societies develop advantages in organization, technology, or resource mobilization that allow them to dominate neighboring regions. They expand through military conquest, economic integration, and cultural assimilation, reaching maturity by developing administrative systems, infrastructure, and ideologies that legitimize their rule. Eventually, they decline due to some combination of internal corruption, economic stagnation, environmental challenges, and external pressures. This cyclical pattern has repeated across continents and millennia, from the river valley civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt to the industrial empires of the 19th century and the superpower competition of the 20th century. The lessons of imperial rise and fall remain relevant in our contemporary world. First, no power, however dominant, remains supreme forever—hubris and overextension have repeatedly undermined seemingly invincible empires from Rome to the Soviet Union. Second, successful societies adapt to changing conditions rather than rigidly maintaining traditions that no longer serve their needs, as demonstrated by the Byzantine Empire's thousand-year survival through constant reinvention. Third, legitimate governance requires balancing central authority with respect for diverse local conditions and stakeholder interests, as the Persian Empire's multicultural approach demonstrated. Finally, environmental sustainability is crucial for long-term survival—many historical empires collapsed partly due to resource depletion or climate changes that undermined their agricultural base. By studying these patterns, we gain perspective on our current global challenges and perhaps wisdom to navigate them more effectively than our predecessors.

Best Quote

“400 million Africans are born-again Christians and the various sects of Christianity are well represented in this small town, from the Church of Wonderful Miracles to the Church of the Best Future, and there is also a large Muslim community. People give around 10% of their meagre incomes to these groups – that’s far more than the government takes in taxation. And it’s made some of Africa’s church leaders multimillionaires with private jets, megachurches, video productions and publishing houses all preying on the desperate.” ― Gaia Vince, Adventures in the Anthropocene: A Journey to the Heart of the Planet we Made

Review Summary

Strengths: The review notes an interesting discussion on geoengineering, albeit superficially treated.\nWeaknesses: The book is described as a mediocre travelogue with obnoxious messages of hope and a dull conclusion. The narrative is criticized for being predictable and lacking depth, with an overly optimistic and cheesy vision of the future. The review also implies a lack of originality, comparing it unfavorably to mainstream climate change literature.\nOverall Sentiment: Critical\nKey Takeaway: The reviewer finds "Adventures in the Anthropocene" to be a predictable and superficial exploration of climate change, lacking in depth and originality, with an unsatisfying conclusion.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.