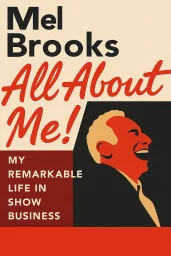

All About Me!

My Remarkable Life in Show Business

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Memoir, Audiobook, Autobiography, Biography Memoir, Humor, Film, Comedy

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2021

Publisher

Ballantine Books

Language

English

ASIN

059315911X

ISBN

059315911X

ISBN13

9780593159118

File Download

PDF | EPUB

All About Me! Plot Summary

Introduction

In the pantheon of American comedy, few figures loom as large or laugh as loudly as Mel Brooks. Born Melvin Kaminsky to Jewish immigrants in Depression-era Brooklyn, Brooks transformed himself from a scrappy street performer into one of entertainment's most versatile and influential voices. His journey from the tenements of Williamsburg to Hollywood royalty represents not just a personal triumph but a revolution in how comedy could address society's most sensitive subjects. Through his groundbreaking films, recordings, and stage productions, Brooks weaponized humor against prejudice, pomposity, and power, proving that laughter could simultaneously entertain and enlighten. What makes Brooks truly remarkable is his fearless approach to comedy coupled with his mastery across multiple media. Throughout his career, he has displayed an uncanny ability to push boundaries while maintaining a fundamental humanity and warmth. Whether satirizing Hitler in "The Producers," confronting racism in "Blazing Saddles," or lovingly parodying classic film genres, Brooks understood that comedy at its best does more than provoke laughter—it challenges assumptions, deflates pretensions, and creates community through shared joy. His evolution from television writer to filmmaker to Broadway composer demonstrates not just versatility but a restless creative spirit that refuses to be confined by convention or expectation. In exploring Brooks' remarkable journey, we discover not just the biography of a brilliant comedian but a master class in using humor as a weapon of joy.

Chapter 1: Brooklyn Beginnings: Finding Humor in Hardship

The streets of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, during the Great Depression formed the unlikely crucible where Mel Brooks' comedic sensibility was forged. Born Melvin Kaminsky in 1926 to Jewish immigrants, Brooks experienced hardship early when his father died of kidney disease when Mel was just two years old. This loss left his mother Kate struggling to support four sons by working as a garment worker. Despite these difficult circumstances, Brooks later recalled his childhood with surprising fondness, describing a neighborhood rich in characters and a household where laughter served as emotional currency. "There was no money for toys," Brooks once reflected, "so I had to use my imagination. I became the entertainment." This early role as family entertainer proved formative. Small in stature and lacking physical strength, young Mel discovered that humor could serve as both shield and sword in the rough-and-tumble world of Brooklyn streets. "When you're a little guy, you're either going to be a victim or you're going to be funny," Brooks explained. "I chose funny." This strategic deployment of humor became a survival mechanism that would later evolve into a sophisticated comedic philosophy. At neighborhood movie theaters, Brooks absorbed the physical comedy of Charlie Chaplin and the anarchic spirit of the Marx Brothers, influences that would later surface in his own work. World War II interrupted Brooks' education, and at 17, he was drafted into the Army. His wartime experiences, including participating in the Battle of the Bulge and defusing land mines across Europe, provided both perspective and material. The absurdity of war, with its juxtaposition of horror and mundanity, deepened his understanding of how humor functions in extreme situations. Brooks later noted that his Jewish identity made fighting Nazi Germany particularly meaningful, creating a personal connection to history that would later inform his most controversial comedy. After the war, he returned to Brooklyn with a broader worldview and a determination to pursue entertainment as a career. The post-war years found Brooks struggling to establish himself, playing drums in the Catskill Mountains resorts known as the "Borscht Belt" while developing his skills as a stand-up comedian. These Jewish vacation destinations served as informal comedy academies where performers learned to read audiences and recover from failed jokes—essential training for Brooks' future career. His breakthrough came when he was hired as a writer for Sid Caesar's pioneering television show "Your Show of Shows" in 1950. Suddenly, the Brooklyn kid who used humor as a defense mechanism found himself in a legendary writers' room alongside talents like Carl Reiner, Neil Simon, and Larry Gelbart. This television apprenticeship taught Brooks the craft of comedy writing—how to structure jokes, build comedic sequences, and write for specific performers. The pressure of creating ninety minutes of live comedy each week forced him to develop discipline alongside his natural improvisational gifts. Brooks specialized in creating outlandish characters for Caesar, including the "2000 Year Old Man" prototype that would later become his own signature character. The intensity of the writers' room, where ideas were pitched, defended, and refined in heated exchanges, honed Brooks' competitive edge while teaching him the value of collaboration. By the late 1950s, Brooks had established himself as a brilliant comedy writer, but his ambitions extended beyond television. His Brooklyn upbringing had instilled in him both insecurity and audacity—a combination that drove him to take risks while constantly seeking approval through laughter. This paradoxical psychology would fuel his subsequent career moves, pushing him to challenge conventions while maintaining a deep connection to traditional comedy forms. The street-smart kid from Williamsburg was preparing to revolutionize American comedy, armed with nothing more than his wit and the hard-earned wisdom that humor could transform pain into power.

Chapter 2: Television Breakthrough: The Caesar Years

Mel Brooks' career took a decisive turn when he joined the writing staff of Sid Caesar's groundbreaking television program "Your Show of Shows" in 1950. The writers' room became legendary for its concentration of comedic talent, including Carl Reiner, Neil Simon, Larry Gelbart, and Mel Tolkin. In this pressure-cooker environment, Brooks thrived despite—or perhaps because of—the intense competition. The show's format, featuring ninety minutes of live comedy each week, created enormous demands but also unlimited opportunities for creative expression. Brooks later described this period as "comedy graduate school," where he learned to craft material under deadline pressure while navigating the complex dynamics of collaborative creation. The writers' room operated like a comedic laboratory, with ideas pitched, debated, and refined through a process that was often contentious but remarkably productive. Brooks became known for his explosive energy and willingness to physically act out his concepts, sometimes standing on furniture or throwing himself across the room to demonstrate a gag. This theatrical approach reflected his understanding that comedy is as much about performance as writing. Caesar recognized Brooks' unique talents, often assigning him to create the most outlandish characters and situations. This vote of confidence boosted Brooks' creative courage, encouraging him to push boundaries and trust his comedic instincts. Working with Caesar taught Brooks the importance of character-driven comedy. Rather than simply stringing together jokes, the show created memorable characters whose personalities generated humor organically. Brooks specialized in developing eccentric figures like Professor Ludwig von Schweinhund, a pompous German "expert" whose mangled English and absurd pronouncements delighted audiences. This character contained early seeds of what would become Brooks' signature approach: using comedy to deflate authority figures and expose the absurdity of pretension. The experience also taught him how to write for specific performers, tailoring material to highlight their strengths while minimizing weaknesses—a skill that would prove invaluable when he began directing his own films. When "Your Show of Shows" ended in 1954, Brooks continued working with Caesar on "Caesar's Hour" until 1957. During this period, his friendship with Carl Reiner deepened, leading to their creation of "The 2000 Year Old Man" routine. What began as an improvised party entertainment—with Reiner interviewing Brooks as a 2000-year-old witness to history—evolved into a cultural phenomenon through albums and television appearances. The character allowed Brooks to combine historical satire with contemporary commentary, all delivered in a distinctive Yiddish-inflected voice that connected to his cultural roots while appealing to mainstream audiences. This breakthrough as a performer expanded Brooks' creative identity beyond writing, setting the stage for his later multi-faceted career. The end of the Caesar shows in 1957 thrust Brooks into a period of professional uncertainty. Despite his television success, he struggled to find consistent work and suffered anxiety attacks that led him to seek psychotherapy. This difficult transition forced Brooks to reevaluate his career and consider new directions. He worked on Broadway revues, created comedy albums, and wrote for television specials, but these projects failed to provide the creative satisfaction or financial stability he sought. The experience of professional insecurity, however painful, ultimately pushed Brooks to take greater creative risks and seek more control over his work—a journey that would eventually lead him to filmmaking. In 1965, Brooks partnered with Buck Henry to create the spy parody series "Get Smart" for NBC. The show, starring Don Adams as the bumbling secret agent Maxwell Smart, cleverly satirized the popular James Bond films and Cold War espionage tropes. Brooks' gift for parody found perfect expression in the show's catchphrases and ridiculous spy gadgets like the "Cone of Silence" and "Shoe Phone." The success of "Get Smart," which ran for five seasons and won multiple Emmy Awards, reestablished Brooks' television credentials while pointing toward his future as a creator of genre parodies. More importantly, it provided the financial security that allowed him to pursue his growing ambition to write and direct films—a medium where his unique comedic vision could find its fullest expression.

Chapter 3: The 2000 Year Old Man: Creating Iconic Characters

The creation of "The 2000 Year Old Man" represents one of the most serendipitous moments in comedy history. The character emerged spontaneously during a break in the Caesar's Hour writers' room when Carl Reiner, inspired by a documentary about elderly people, began interviewing Brooks as if he were thousands of years old. Brooks immediately responded in a Yiddish-inflected accent, improvising outrageous answers about historical events he had supposedly witnessed. What began as a private entertainment for friends evolved into a cultural phenomenon that would span decades, producing five comedy albums and numerous television appearances. The routine's success revealed Brooks' extraordinary gift for character creation and improvisation—talents that would later define his film career. The genius of the 2000 Year Old Man character lay in its perfect balance of historical satire and contemporary commentary. When asked about the greatest invention he had witnessed, the ancient man bypassed obvious choices like electricity or the automobile to declare, "Saran Wrap... because you can put a sandwich in it, and you can see the sandwich!" This combination of historical perspective and mundane concerns created a comedic tension that audiences found irresistible. The character also allowed Brooks to incorporate his Jewish cultural heritage into mainstream entertainment, with the 2000 Year Old Man's accent and sensibilities clearly rooted in the Eastern European Jewish experience. At a time when ethnic humor was often relegated to niche audiences, Brooks found a way to make these cultural references universally appealing. The improvisational nature of the routine showcased Brooks' remarkable mental agility. Reiner never told Brooks what questions he would ask, forcing him to create answers on the spot. This spontaneity gave the performances an electric quality, with audiences witnessing the creation of comedy in real time. Brooks later explained that the key to successful improvisation was "never saying no" to whatever premise was established. This philosophy of fearless acceptance would later inform his approach to filmmaking, where he encouraged actors to take risks and followed creative impulses wherever they led. The 2000 Year Old Man also demonstrated Brooks' gift for creating fully realized characters with distinctive voices, perspectives, and psychological quirks—a talent that would blossom in his later film work. Initially, Brooks was hesitant to record the routine commercially, concerned that the Jewish humor might be too specific or potentially offensive to wider audiences. This reluctance revealed an insecurity that often accompanied his boldest creative choices—a fear that what made him laugh might not translate to others. It took encouragement from friends like George Burns and Steve Allen to convince Brooks and Reiner to record their first album in 1960. The record's success, and the positive reception from non-Jewish audiences, taught Brooks an important lesson about the universal appeal of specific cultural experiences when presented with authenticity and humor. This realization would later embolden him to incorporate his Jewish perspective into films like "The Producers" and "History of the World, Part I." The 2000 Year Old Man became more than just a successful comedy routine—it established a template for Brooks' approach to historical and cultural material. By viewing history through the eyes of an ordinary person who happened to live through extraordinary times, Brooks found a way to humanize grand historical narratives while exposing their absurdities. This perspective would later inform films like "History of the World, Part I," where Brooks applied the same irreverent approach to historical events from the Stone Age to the French Revolution. The character also demonstrated Brooks' understanding that comedy could address serious subjects—mortality, religion, politics—while remaining fundamentally entertaining. This balance between substance and silliness would become the hallmark of Brooks' mature work. The enduring popularity of the 2000 Year Old Man—the final album was recorded in 1997, nearly forty years after the character's creation—testifies to the timelessness of Brooks' comedic vision. By creating a character who had literally seen it all, Brooks found a vehicle for commenting on everything from ancient history to contemporary culture. The routine's longevity also reflects the remarkable creative partnership between Brooks and Reiner, whose friendship and professional collaboration spanned over seventy years. Their chemistry, with Reiner providing the perfect straight-man foundation for Brooks' comic flights, established a model for comedic duos that continues to influence performers today. In the 2000 Year Old Man, Brooks created not just a memorable character but an enduring comedic perspective that transcended its origins to become part of American cultural heritage.

Chapter 4: Directing Revolution: Breaking Taboos Through Laughter

Mel Brooks' transition from television writer to film director represented not just a career evolution but a revolutionary approach to comedy filmmaking. His directorial debut, "The Producers" (1967), established what would become his signature style: fearless, boundary-pushing comedy that used laughter to confront subjects others considered taboo. The film's premise—two theatrical producers deliberately creating a tasteless musical about Hitler to guarantee a flop—allowed Brooks to directly address the lingering trauma of World War II and the Holocaust through satire. As a Jewish veteran who had fought against Nazi Germany, Brooks understood the power of ridicule as a weapon against fear. "If you can make people laugh at Hitler," he explained, "then you've won." This philosophy of using comedy to confront uncomfortable truths reached its apotheosis in "Blazing Saddles" (1974), Brooks' audacious Western parody that tackled American racism with unprecedented directness. Co-written with Richard Pryor, the film featured a Black sheriff protecting a racist town, creating situations that exposed the absurdity of prejudice while delivering non-stop laughs. Brooks refused to soften the film's language or situations, insisting that authentic racial epithets were necessary to expose the ugliness of racism. This commitment to uncomfortable truth represented a new approach to comedy filmmaking—one that trusted audiences to understand the difference between depicting racism and endorsing it. The film's enormous commercial success proved that viewers were ready for comedy that challenged social conventions while remaining fundamentally entertaining. Brooks' revolutionary approach extended beyond content to form, as demonstrated by "Blazing Saddles'" famous fourth-wall-breaking finale. When the Western set literally collapses and the characters spill onto a Hollywood backlot and into a neighboring musical, Brooks signaled his interest in deconstructing not just genre conventions but the artifice of filmmaking itself. This meta-theatrical awareness, combined with anachronistic references and deliberate continuity errors, created a new kind of comedy that commented on its own creation. Brooks understood that modern audiences were increasingly sophisticated about film conventions and could appreciate humor that played with these expectations. This self-referential approach influenced generations of filmmakers and anticipated the postmodern sensibility that would later dominate much of American comedy. While pushing boundaries in content and form, Brooks also revolutionized the business of comedy filmmaking. After struggling to secure backing for "The Producers," he insisted on greater creative control for subsequent projects. For "Blazing Saddles," he negotiated with Warner Bros. to direct the film himself, refusing to compromise his vision despite studio concerns about the provocative material. This determination to maintain artistic integrity, even when it meant battling studio executives, established a model for comedy directors who viewed themselves as auteurs rather than hired hands. Brooks demonstrated that comedy deserved the same creative respect accorded to dramatic filmmaking, elevating the genre's status within the industry. Brooks' directorial revolution was not limited to social commentary. With "Young Frankenstein" (1974), he demonstrated that parody could be both loving and subversive, honoring cinematic traditions while playfully undermining them. Shot in gorgeous black and white with period-appropriate techniques, the film showed Brooks' deep knowledge of and affection for the Universal horror films he was parodying. This approach—understanding genre conventions deeply enough to subvert them meaningfully—distinguished Brooks' parodies from simple mockery. It established a template for intelligent genre comedy that influenced filmmakers from Jim Abrahams and the Zucker brothers to Edgar Wright and Taika Waititi. By the mid-1970s, Brooks had fundamentally transformed American film comedy, creating a body of work that was simultaneously accessible and sophisticated, outrageous and thoughtful. His willingness to tackle sensitive subjects through humor opened new territories for comedy, while his technical innovations expanded the formal possibilities of the genre. Most importantly, Brooks demonstrated that comedy could serve a serious purpose—confronting fears, exposing hypocrisies, and challenging social norms—without sacrificing its primary mission to entertain. This revolutionary approach established Brooks as not just a successful filmmaker but a cultural force whose influence would extend far beyond his own productions to shape the very nature of American comedy.

Chapter 5: Genre Parodies: Mastering the Art of Loving Mockery

Mel Brooks elevated film parody to an art form by combining deep knowledge of cinematic traditions with an irreverent willingness to subvert them. Unlike many imitators who merely referenced familiar scenes, Brooks created parodies that functioned as both loving tributes and incisive commentaries on their source material. "Young Frankenstein" (1974) exemplifies this approach, recreating the atmosphere of Universal horror films with such attention to detail that Brooks insisted on using the original laboratory equipment from the 1931 "Frankenstein." Shot in gorgeous black and white with period-appropriate techniques like iris transitions and dramatic shadows, the film demonstrated Brooks' remarkable ability to capture the essence of a genre while playfully undermining its conventions. This balance between reverence and irreverence became the hallmark of Brooks' parodic style. Brooks continued his exploration of genre with "Silent Movie" (1976), a nearly wordless comedy that paid homage to the silent film era while satirizing contemporary Hollywood. The film's central joke—a silent movie about making a silent movie in the age of talkies—allowed Brooks to showcase his gift for visual comedy while commenting on the film industry's resistance to innovation. The film's one spoken word—"Non!" delivered by mime Marcel Marceau—exemplified Brooks' talent for ironic humor. By successfully creating a silent comedy for modern audiences, Brooks demonstrated that fundamental aspects of visual humor remained timeless, connecting his work to comedy pioneers like Chaplin and Keaton whom he had admired since childhood. "High Anxiety" (1977) represented Brooks' tribute to Alfred Hitchcock, recreating iconic scenes from films like "Vertigo," "Psycho," and "The Birds" with comedic twists. Brooks' personal relationship with Hitchcock, who appreciated the homage and gave Brooks a case of expensive wine after viewing the film, added a touching dimension to the project. Beyond simply parodying famous sequences, Brooks captured Hitchcock's distinctive visual style and thematic preoccupations, demonstrating his sophisticated understanding of what made the Master of Suspense's work so effective. The film revealed Brooks' evolution as a director, showing increased confidence in his visual storytelling and a willingness to take on more complex cinematic references. "Spaceballs" (1987) took aim at science fiction epics, particularly "Star Wars," translating Brooks' parodic approach to a new generation of filmmakers and audiences. The film combined visual gags (like the impractically long spaceship in the opening sequence) with verbal wit and character-based humor. Brooks played with the commercialization of movie franchises through the film's extensive merchandising jokes, presciently commenting on Hollywood's growing dependence on product tie-ins. While maintaining his signature irreverence, Brooks showed genuine affection for the space opera genre, creating characters and situations that honored their sources while finding fresh comedic angles. What distinguished Brooks' parodies from lesser imitators was his understanding that effective parody requires more than reference-spotting. His films worked on multiple levels: as comedies that could be enjoyed without knowledge of their sources, as loving tributes that demonstrated genuine appreciation for film history, and as commentaries that exposed the conventions and sometimes the limitations of popular genres. Brooks never settled for easy mockery, instead finding humor in the tension between his reverence for cinema and his irrepressible impulse to subvert expectations. This sophisticated approach to parody influenced generations of filmmakers and established genre comedy as a legitimate artistic form rather than merely a parasitic one. The success of Brooks' parodies stemmed from his unique position as both outsider and insider—someone who loved films enough to study them deeply but maintained enough critical distance to see their absurdities. This perspective allowed him to create comedies that appealed to both casual moviegoers and serious cinephiles. By treating comedy with the same technical care and artistic ambition as dramatic filmmaking, Brooks elevated parody from a minor subgenre to a significant form of cinematic expression. His genre explorations demonstrated that comedy could be simultaneously accessible and sophisticated, entertaining and insightful—a balance that defines Brooks' enduring contribution to American film.

Chapter 6: Beyond Comedy: Brooksfilms and Dramatic Productions

In 1980, Mel Brooks made a surprising career pivot by establishing Brooksfilms, a production company dedicated to serious dramatic films that might otherwise struggle to find backing in Hollywood. This move revealed a side of Brooks that many fans of his comedies might not have suspected: a deep appreciation for thoughtful, challenging cinema and a desire to use his industry clout to bring important stories to the screen. The company's first major production, David Lynch's "The Elephant Man," told the poignant true story of John Merrick, a severely deformed man in Victorian London who found dignity despite being treated as a sideshow attraction. Brooks deliberately kept his name off the marketing materials, concerned that audiences would expect a comedy and be disappointed. The critical and commercial success of "The Elephant Man"—including eight Academy Award nominations—established Brooksfilms as a serious production entity and revealed Brooks' sophisticated understanding of cinema beyond comedy. He showed remarkable instinct in selecting projects and directors, often taking chances on relatively unknown filmmakers with unique visions. This was evident in his decision to back David Cronenberg's "The Fly" (1986), a horrifying yet emotionally resonant reimagining of the 1950s science fiction classic. Brooks recognized in Cronenberg's body-horror approach a powerful metaphor for disease and mortality that transcended the limitations of the genre. His willingness to support such challenging material demonstrated his commitment to cinema as an art form capable of exploring profound human experiences. Perhaps most surprising was Brooks' production of "84 Charing Cross Road" (1987), a gentle, epistolary drama about the twenty-year correspondence between a New York writer and a London bookseller. Starring his wife Anne Bancroft alongside Anthony Hopkins, the film showcased Brooks' appreciation for quiet, character-driven storytelling—a stark contrast to the anarchic energy of his comedies. Through Brooksfilms, Brooks also produced "Frances" (1982), a biographical drama about troubled actress Frances Farmer starring Jessica Lange, and "My Favorite Year" (1982), a comedy-drama inspired by his own early television experiences with Sid Caesar. These productions revealed Brooks' range as a producer and his ability to recognize and nurture diverse talents. Brooks' dual career as comedy director and drama producer reflected his understanding that these seemingly opposite modes share fundamental concerns with human experience. The same empathy that informed his best comedy allowed him to recognize the emotional power in dramatic stories. Similarly, his comedic sense of timing and structure enhanced his ability to shape dramatic narratives as a producer. This crossover of skills demonstrated Brooks' sophisticated understanding of storytelling across genres and his recognition that effective comedy and drama both require emotional truth and technical precision. While maintaining distinct identities for his comedic and dramatic work, Brooks brought the same intelligence and humanity to both endeavors. The establishment of Brooksfilms also revealed Brooks' generosity as an artist and his commitment to cinema beyond his personal projects. By using his success to support other filmmakers' visions, he demonstrated a love of storytelling that transcended ego and commercial considerations. This generosity extended to his approach to producing, where he provided guidance and protection while allowing directors creative freedom. David Lynch praised Brooks as "the greatest producer" precisely because he shielded filmmakers from studio interference while offering constructive feedback. This balanced approach to production reflected Brooks' own experience with creative constraints and his desire to create an environment where artistic vision could flourish. Brooks' work beyond comedy expanded perceptions of his talents and contributions to cinema. While his comedies had established him as a significant filmmaker, his dramatic productions revealed the depth of his cinematic understanding and his ability to recognize important stories across genres. This dual legacy—as both a revolutionary comedy director and a discerning producer of serious films—distinguishes Brooks from many of his contemporaries and demonstrates the breadth of his impact on American cinema. By transcending the limitations of being categorized solely as a comedian, Brooks established himself as a complete filmmaker whose influence extends throughout the industry and across multiple genres.

Chapter 7: Broadway Triumph: Reinvention in Later Years

In 2001, at an age when most filmmakers would be contemplating retirement, Mel Brooks reinvented himself yet again by transforming his first film into a Broadway musical. "The Producers" on Broadway represented both a return to Brooks' roots and a bold new challenge. Though he had written songs for his films, creating a full Broadway score required a different level of musical sophistication. Brooks embraced the challenge with characteristic enthusiasm, writing both music and lyrics for the show while collaborating with Thomas Meehan on the book. The result was not merely an adaptation but a reinvention that expanded the original's premise into a full-blown musical extravaganza. The show's development wasn't without challenges. Original director Mike Ockrent died during pre-production, leaving his wife, choreographer Susan Stroman, to take over directorial duties while grieving. Brooks showed remarkable sensitivity during this difficult transition, supporting Stroman while maintaining the production's momentum. His instinct for casting proved flawless once again, with Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick creating an iconic partnership as Max Bialystock and Leo Bloom. Their chemistry captured the spirit of the original film while bringing fresh energy to the material. The production's success demonstrated Brooks' ability to adapt his comedic vision to new forms while maintaining its essential qualities. When "The Producers" opened on Broadway, it became an immediate sensation. The show received unprecedented acclaim, with critics praising Brooks' witty lyrics, catchy melodies, and the production's gleeful embrace of traditional Broadway spectacle. The centerpiece "Springtime for Hitler" number, which had shocked film audiences decades earlier, now became a show-stopping theatrical set piece that had audiences simultaneously gasping and roaring with laughter. The musical captured the essence of Brooks' comedic philosophy: that the best way to combat evil is to make it ridiculous through laughter. This principle, which had guided his work since "The Producers" film, found its fullest expression in the Broadway adaptation. The show's success at the 2001 Tony Awards was historic, winning an unprecedented 12 awards including Best Musical, Best Book, and Best Original Score for Brooks. This triumph completed Brooks' EGOT status—having won Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony awards—a rare achievement that demonstrated his remarkable versatility as an artist. For Brooks, who had grown up loving musical theater, this Broadway success represented a particularly sweet victory. It also introduced his distinctive comic sensibility to a new generation and a new medium, proving that his approach to comedy remained relevant and powerful decades after he first developed it. The success of "The Producers" musical led Brooks to adapt another of his classic films, "Young Frankenstein," for Broadway in 2007. Though it didn't match the commercial or critical success of its predecessor, the production further demonstrated Brooks' commitment to exploring new creative territories even in his eighties. This willingness to take risks and embrace new challenges has characterized Brooks' entire career, from his early days in television to his late-life Broadway triumphs. Rather than resting on his considerable laurels, Brooks has consistently sought new ways to express his comedic vision and connect with audiences across generations. In his later years, Brooks has embraced his role as a living legend of American comedy while refusing to become merely a monument to past achievements. He has performed one-man shows, written a memoir, and continued to appear in interviews and documentaries, sharing his experiences and insights with characteristic wit and energy. His influence extends beyond his own productions to the countless comedians and filmmakers who have been inspired by his fearless approach to comedy. By continually reinventing himself and his work, Brooks has ensured that his comedic vision remains vital and relevant, transcending the limitations of time and changing tastes to speak to fundamental human experiences through the universal language of laughter.

Summary

Mel Brooks' extraordinary journey from the streets of Brooklyn to the heights of Hollywood and Broadway represents one of the most remarkable careers in American entertainment history. His fundamental insight—that comedy could simultaneously entertain and challenge, provoke and heal—revolutionized American humor and expanded the boundaries of what comedy could accomplish. Through his work across multiple decades and media, Brooks demonstrated that laughter is not merely a diversion but a powerful tool for confronting uncomfortable truths about society, history, and human nature. His willingness to risk offense in pursuit of deeper comedic truths paved the way for generations of comedians who followed, while his technical mastery of filmmaking elevated comedy to an art form deserving of serious consideration. The enduring lesson of Brooks' career is that authentic creative expression, pursued with both passion and craft, can transcend initial expectations and limitations to achieve lasting cultural significance. His evolution from television writer to filmmaker to Broadway composer demonstrates the value of continual reinvention and risk-taking, even in the face of potential failure. For audiences, Brooks' work offers not just entertainment but a perspective on life that acknowledges its absurdities and injustices while finding joy and meaning through shared laughter. His legacy reminds us that humor, at its most powerful, does more than amuse—it illuminates, connects, and liberates. In a world increasingly divided by ideology and identity, Brooks' ability to find common ground through laughter offers a model for how comedy at its best can bridge differences while never shying away from uncomfortable truths.

Best Quote

“Comedy is a very powerful component of life. It has the most to say about the human condition because if you laugh you can get by. You can struggle when things are bad if you have a sense of humor. Laughter is a protest scream against death, against the long goodbye. It’s a defense against unhappiness and depression.” ― Mel Brooks, All about Me!: My Remarkable Life in Show Business

Review Summary

Strengths: The review effectively captures a vivid childhood memory, using humor and nostalgia to engage the reader. The dialogue between the child and the mother is particularly well-crafted, illustrating a relatable and endearing family dynamic. The anecdote is rich in detail, providing a clear sense of time and place.\nOverall Sentiment: The sentiment is warm and humorous, with a touch of nostalgia. The reviewer shares a personal and relatable experience, evoking a sense of empathy and amusement.\nKey Takeaway: The review highlights the impact of early childhood experiences on one's imagination and fears, using a humorous anecdote to illustrate how a child's perception can be shaped by popular culture and family interactions.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.