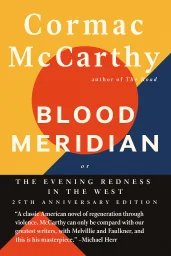

Blood Meridian

Or the Evening Redness in the West

Categories

Fiction, Classics, Horror, Historical Fiction, Literature, Westerns, American, Historical, Novels, Literary Fiction

Content Type

Book

Binding

Paperback

Year

2010

Publisher

Vintage Books

Language

English

ASIN

B0DSZLN57Y

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Blood Meridian Plot Summary

Introduction

The American Southwest of the mid-19th century was a landscape of extraordinary violence, a borderland where civilization's veneer peeled away to reveal humanity at its most primal. Following the Mexican-American War, this region became a theater of brutality where scalp hunters, indigenous tribes, settlers, and soldiers engaged in a relentless cycle of bloodshed. What drove men to such extremes? How did government policies incentivize mass killing? And what happens when violence becomes not just a means to an end, but a profitable industry? This book plunges readers into this unforgiving world through the experiences of those who participated in America's westward expansion—revealing how institutions of civilization not only failed to prevent atrocities but actively encouraged them. Through unflinching accounts of frontier violence, readers will confront uncomfortable truths about American history: that genocide was not incidental but instrumental to nation-building, that intellectual justifications transformed brutality into policy, and that the commodification of death created markets for human remains. Those seeking to understand the dark undercurrents of American history, the nature of violence in human affairs, or the philosophical questions surrounding evil will find this unflinching account both disturbing and illuminating.

Chapter 1: The Borderlands: A Lawless Territory After the Mexican-American War

By 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had formally ended the Mexican-American War, transferring vast territories to the United States while creating a borderland of uncertain jurisdiction. This newly established frontier existed in a power vacuum—too distant for effective American governance, yet no longer under Mexican control. The result was a lawless territory where violence became the primary means of resolving disputes and establishing dominance. The landscape itself seemed to encourage brutality—a harsh desert environment where resources were scarce and survival precarious. Contemporary accounts described the region as "a terra damnata," a cursed land where conventional morality held no sway. Travelers crossing this territory encountered abandoned settlements, sun-bleached bones, and the aftermath of massacres—evidence of the violence that had become endemic to the region. The border was not merely a political boundary but a psychological frontier where the constraints of civilization weakened with each mile traveled westward. This lawlessness attracted a particular breed of men—veterans of the Mexican-American War who had developed a taste for violence, adventurers seeking fortune without moral constraint, and fugitives fleeing justice. These men formed loose bands that operated beyond the reach of law, taking advantage of the region's instability to pursue their own violent agendas. Neither American nor Mexican authorities could effectively police this territory, creating perfect conditions for predatory behavior on an unprecedented scale. Indigenous communities found themselves caught in this maelstrom. Apache and Comanche groups, already engaged in their own complex conflicts with Mexican settlements, now faced new threats from American expansion. Their resistance to encroachment was fierce and sophisticated, employing guerrilla tactics that frustrated conventional military responses. This resistance, however, would be used to justify some of the most brutal campaigns of extermination in American history. The borderlands of 1848-1850 represent a critical but often overlooked period in American history—a time when the nation's expansion was driven not by noble pioneers but by men whose primary skill was violence. The chaos of this period would establish patterns of conflict between settlers and indigenous peoples that would persist for decades, while the moral compromises made in the name of territorial acquisition would leave a lasting stain on American identity. As one contemporary observer noted, "What we witnessed in those territories was not the advance of civilization, but its retreat."

Chapter 2: Captain White's Expedition: Manifest Destiny and Indigenous Resistance

In the spring of 1849, Captain White, a former military officer, assembled a filibustering expedition to claim Mexican territory for American interests. White embodied the ideology of Manifest Destiny—the belief that American expansion was divinely ordained and inevitable. "We are to be the instruments of liberation in a dark and troubled land," he proclaimed to his recruits, framing their mission as a civilizing force rather than an invasion. His expedition attracted a diverse group of men, from idealistic young adventurers to hardened veterans seeking profit through conquest. White's rhetoric reflected the racial hierarchies that underpinned American imperialism. He described Mexicans as "a race of degenerates" incapable of self-governance and indigenous peoples as obstacles to progress that must be removed. This dehumanizing language served a crucial purpose—it transformed what would otherwise be recognized as theft and murder into a righteous mission. The expedition members were encouraged to see themselves not as invaders but as agents of historical inevitability, bringing American values to "savage" territories. The expedition's encounter with Comanche warriors on the plains of Texas revealed the gap between imperial rhetoric and frontier reality. The Comanches, described by witnesses as "a legion of horribles" in their war paint and regalia, demonstrated tactical superiority that American military training could not match. Their mounted warfare, developed over generations of plains combat, overwhelmed White's company. The captain himself was beheaded, his preserved head later displayed as a warning to other would-be conquerors. This defeat illustrated how indigenous resistance was not merely desperate defense but sophisticated warfare adapted to the specific conditions of the borderlands. The aftermath of White's failed expedition rippled through American policy. Rather than reconsidering the wisdom of westward expansion, authorities concluded that more aggressive measures were necessary. Military campaigns against indigenous communities intensified, while private enterprises emerged to profit from the conflict. The defeat of White's expedition did not diminish American imperial ambitions but rather hardened them, replacing idealistic rhetoric with pragmatic brutality. This pattern—ideological justification followed by violent implementation, indigenous resistance, and escalating brutality—would repeat throughout the conquest of the American West. Captain White's expedition represents a microcosm of this larger historical process, revealing how Manifest Destiny functioned not merely as abstract philosophy but as practical justification for violence. The expedition's failure demonstrated that conquest would require more than rhetoric; it would demand systematic extermination campaigns that later generations would struggle to reconcile with American ideals of liberty and justice.

Chapter 3: The Scalp Trade: Government Bounties and Systematic Extermination

By 1849, the Mexican state of Chihuahua had implemented a bounty system that would transform the borderlands into a theater of unprecedented violence. Governor Ángel Trias, facing persistent Apache raids on settlements, offered 100 pesos for each Apache scalp and 1,000 for the head of prominent leaders. This policy effectively privatized warfare, creating economic incentives for what would become industrial-scale killing. The bounty system attracted mercenaries from across the borderlands, men who saw in this policy an opportunity to profit from violence they were already inclined to commit. The commodification of death through the scalp trade represented a perverse innovation in genocide. Unlike previous conflicts where violence served territorial or political ends, the bounty system made killing profitable in itself. Scalp hunters developed efficient methods for their grim work—attacking villages at dawn when resistance would be minimal, killing indiscriminately, and processing the remains with assembly-line efficiency. One participant described how they would "harvest the bloody fruit" after massacres, carefully preserving the scalps for presentation to authorities. This systematic approach transformed random brutality into organized production, with human remains as the commodity. The economic logic of the scalp trade quickly led to indiscriminate killing. Since authorities had no reliable method to distinguish Apache scalps from those of other indigenous peoples or even Mexican peasants, scalp hunters targeted any vulnerable community. As one hunter admitted, "Any scalp will bring the same price." Peaceful indigenous villages, Mexican settlements, and even travelers with darker complexions became victims of this perverse marketplace. The system created incentives not for precision but for volume—the more scalps delivered, the greater the payment, regardless of their origin. Government complicity in this system revealed the moral bankruptcy of authorities on both sides of the border. When scalp hunters returned to Chihuahua City with their grisly trophies, they received "a hero's welcome," with the scalps "strung about the iron fretwork of the gazebo like decorations for some barbaric celebration." Governor Trias, described as "widely read in the classics" and "a student of languages," represented the complicity of educated elites in systems of extermination. This official sanction transformed what might otherwise have been recognized as criminal behavior into state policy. The legacy of the scalp trade extended far beyond its immediate victims. It established a precedent where genocide became not merely acceptable but incentivized by government policy. The dehumanization necessary to participate in such a system infected broader society, normalizing extreme violence against indigenous peoples and other marginalized groups. When the United States fully established control over these territories, it inherited this legacy of sanctioned brutality—a foundation upon which further policies of indigenous removal and extermination would be built. The scalp trade represents one of the darkest chapters in American expansion, revealing how economic incentives can transform violence from chaotic outbursts into systematic production.

Chapter 4: Judge Holden: Intellectual Justifications for Frontier Violence

Among the most disturbing aspects of frontier violence was its intellectual justification by educated men who provided philosophical frameworks for genocide. Judge Holden exemplified this phenomenon—a seven-foot tall, hairless polymath who combined scientific knowledge with an appetite for destruction. Unlike common scalp hunters motivated primarily by profit, the Judge represented something more insidious: the marriage of Enlightenment rationality with genocidal practice. His encyclopedic knowledge spanned multiple languages, geology, archaeology, music, and warfare, all deployed in service of domination rather than understanding. The Judge's philosophy centered on the idea that "war is god"—not merely a human activity but the fundamental principle of existence. "War was always here," he would lecture his companions around campfires. "Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner." This perspective transformed violence from a regrettable necessity into a cosmic principle, elevating genocide from crime to participation in natural law. By framing extermination as inevitable, the Judge provided intellectual cover for men who might otherwise have questioned their actions. His approach to knowledge revealed the darker potential of scientific inquiry divorced from moral constraints. The Judge meticulously documented artifacts, plants, and geological formations before destroying them, explaining: "That which exists without my knowledge exists without my consent." This statement captured the imperial logic underlying American expansion—the belief that knowledge justified ownership and control, ultimately leading to the erasure of indigenous cultures and peoples. His scientific collection was not preservation but appropriation, a form of epistemological violence that paralleled physical extermination. The historical context for the Judge's character lies in the intellectual currents that justified westward expansion. Scientific racism provided "evidence" that non-white peoples were evolutionarily inferior and destined for extinction. Manifest Destiny framed American conquest as divinely ordained progress. Social Darwinism suggested that the displacement of indigenous peoples was merely natural selection operating at the level of civilizations. The Judge distilled these ideologies to their essence, stripping away moral pretensions to reveal the will to power at their core. The Judge's most disturbing insight was that civilization doesn't oppose violence but organizes and legitimizes it. His presence in the historical borderlands suggests that the atrocities committed there weren't aberrations but logical extensions of mainstream American thought. The intellectual frameworks that justified genocide weren't developed by marginal figures but by respected scientists, philosophers, and statesmen. This legacy continues to haunt American institutions, which were built upon foundations that rationalized extraordinary violence as necessary for progress. The Judge's combination of erudition and brutality serves as a warning about how easily intellectual sophistication can become complicit in atrocity when divorced from moral consideration.

Chapter 5: Glanton's Gang: The Industrialization of Killing for Profit

John Joel Glanton, a former Texas Ranger and veteran of the Mexican-American War, assembled a gang of mercenaries that would become notorious even in a landscape accustomed to violence. Contracted by Mexican authorities to collect Apache scalps, Glanton's operation transformed frontier violence from chaotic outbursts into something resembling an industry. His gang included Americans, Europeans, Mexicans, and even Delaware Indians—a diverse collection of men united only by their willingness to kill for profit. They were equipped with the latest weapons technology, including Colt revolvers that represented a revolution in personal firepower. The operations of Glanton's gang revealed the industrial scale of frontier violence. They attacked villages at dawn, killing indiscriminately—men, women, and children. After one massacre, they rode away "leaving behind on the scourged shore of the lake a shambles of blood and salt and ashes." The scalps were harvested methodically, the victims left "rawskulled and strange in their bloody cauls." This systematic approach transformed violence from emotional outbursts into organized production, with human remains as the commodity. One gang member described their work as "mining for hair," revealing how thoroughly they had commercialized death. The economic incentives driving Glanton's operation created perverse outcomes that accelerated genocide. When Glanton presented a scalp he claimed belonged to a prominent Apache leader (though experts pointed out it clearly didn't), the question wasn't whether the victim was actually the leader but whether "it will pass for him." Truth became irrelevant in a system where appearance was all that mattered for payment. This commodification of death would have profound consequences for the region, intensifying cycles of revenge and retaliation that would continue for decades. As Glanton's gang moved through the borderlands, they left devastated communities in their wake. Their attacks followed a pattern: they entered a settlement, initially welcomed as protectors, only to transform into predators. In one village that had suffered from Apache raids, they were "fallen upon as saints" with gifts of food and celebration. When they departed three days later, "the streets stood empty, not even a dog followed them to the gates." This pattern of betrayal compounded the physical destruction, undermining the possibility of trust between communities that might otherwise have formed alliances against common threats. The industrialization of killing represented by Glanton's gang foreshadowed modern forms of organized violence. Their operation combined economic incentives, technological advantages, and systematic methods in ways that anticipated later developments in warfare and genocide. The transformation of killing from emotional reaction to calculated production represents one of the most disturbing aspects of frontier violence—not merely that it occurred, but that it was rationalized, systematized, and incentivized by the very institutions meant to establish civilization. Glanton's gang may have operated at the margins of society, but their methods revealed central truths about how violence was being institutionalized during American expansion.

Chapter 6: The Yuma Massacre: Retribution and the Cycle of Violence

By the spring of 1850, Glanton's gang had established control over the ferry crossing at the Colorado River near present-day Yuma, Arizona. After killing the previous operators, they began charging exorbitant rates to travelers heading to California during the Gold Rush, then simply robbing and killing them before dumping their bodies in the river. This operation represented a new level of predation—no longer could they claim to be serving any legitimate purpose, even the dubious one of killing hostile warriors for bounty. Instead, they had become simple bandits, preying on vulnerable migrants drawn west by the promise of gold. The Yuma Indians, who had previously worked with the original ferry operators, watched these developments with growing anger. The gang's brutality extended to the local Yuma population, with gang members raping indigenous women and killing any who resisted. This treatment eventually provoked the Yuma to action. Led by their chief, Caballo en Pelo, they planned a surprise attack on the ferry outpost. The attack came at dawn, catching most of the gang asleep or unprepared. In a swift and brutal assault, they killed Glanton and most of his men, scalping them and throwing their bodies into the fire. The Yuma Massacre represented a form of indigenous resistance that challenged American narratives about frontier violence. Unlike earlier encounters where indigenous groups were portrayed as initiating conflict, this attack was clearly retributive—a response to specific provocations and abuses. The Yuma had attempted to work within the new economic system established by American expansion, only to find themselves victimized by its worst elements. Their violent response demonstrated that indigenous communities were not passive victims but active participants in the struggle to define the terms of coexistence in the borderlands. The aftermath of the massacre revealed how cycles of violence perpetuated themselves across the frontier. American authorities responded to the Yuma attack not by investigating the abuses that provoked it but by launching punitive expeditions against the Yuma people. These campaigns further inflamed tensions and reinforced indigenous perceptions that American expansion was inherently hostile to their existence. The cycle of attack and reprisal continued, with each side pointing to the other's violence as justification for their own. As one military officer observed, "We are locked in a dance of death from which neither side can gracefully withdraw." The Yuma Massacre illustrates how violence in the borderlands was not simply imposed by American expansion but emerged from complex interactions between diverse groups with competing interests. While American policies and economic incentives created conditions for extreme violence, indigenous communities responded with their own strategies of resistance and retribution. This complexity challenges simplistic narratives about American conquest, revealing instead a landscape where violence circulated between multiple actors, each responding to and provoking the others. The massacre stands as a reminder that the violence of this period cannot be understood through one-dimensional accounts of villains and victims, but requires recognition of how systems of violence created their own momentum that consumed all participants.

Chapter 7: The Judge's Dance: Violence as America's Enduring Legacy

As American authority gradually consolidated across the Southwest, the overt brutality of the scalp trade gave way to more institutionalized forms of violence. Military campaigns, reservation policies, and legal structures continued the work that mercenaries had begun, though with the veneer of legitimacy that state power provides. This transition did not represent the triumph of civilization over savagery but rather the incorporation of frontier violence into the fabric of the nation. As Judge Holden observed in one of his campfire lectures: "It makes no difference what men think of war... War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him." The Judge's philosophy that "war is god" proved disturbingly accurate in a landscape where violence became the primary mode of interaction between individuals and groups. His most chilling insight was that civilization doesn't oppose violence but organizes and legitimizes it. In one discourse, he tells his companions: "Only that man who has offered up himself entire to the blood of war... can dance." This dance became a metaphor for participation in the violent foundation of the American nation—those who recognized and embraced this truth could move freely within the new order, while those who resisted it would be consumed. The legacy of frontier violence persisted long after the specific atrocities of the scalp trade had ended. The dehumanization necessary to justify such brutality infected broader American culture, establishing patterns of racial hierarchy that would shape national development for generations. Legal structures, educational systems, and cultural narratives all incorporated assumptions about white supremacy that had been forged in the crucible of frontier violence. As one historian noted, "The methods changed, but the dance continued"—genocide gave way to assimilation policies, military campaigns to legal dispossession, but the fundamental power dynamics remained. For indigenous communities, this legacy meant continued existential threats even after the most overt violence had subsided. Reservation policies concentrated populations in areas with inadequate resources, educational programs aimed to eradicate native languages and cultures, and legal doctrines systematically undermined tribal sovereignty. These approaches represented more sophisticated methods for achieving what scalp hunters had pursued directly—the elimination of indigenous presence from territories claimed by the United States. The dance of violence had become more elaborate but no less deadly in its consequences. The enduring power of this legacy lies in how thoroughly it has been incorporated into American institutions and identity. The violence of the borderlands wasn't an aberration but a foundation upon which modern America was built. The Judge's dance continues in contemporary debates about borders, immigration, and indigenous rights—conflicts that still revolve around questions of who belongs within the national community and who must be excluded. Understanding this history doesn't provide easy answers, but it does demand that we confront the violence embedded in our institutions rather than projecting it safely into a distant past. As the Judge himself might observe, only by acknowledging our participation in this dance can we hope to change its choreography.

Summary

The American Southwest of the mid-19th century emerges through this narrative as a crucible where the darkest aspects of human nature were not merely revealed but institutionalized. The central tension throughout is not between civilization and savagery, but between competing forms of violence—indigenous raids, military campaigns, scalp hunting expeditions—all operating within systems that incentivized brutality. Judge Holden's philosophy that "war is god" proves disturbingly accurate in a landscape where violence became the primary mode of interaction between individuals and groups. The scalp bounty system, ostensibly created to protect settlements, instead accelerated a genocide that consumed perpetrators and victims alike in an expanding cycle of atrocity. The historical lessons from this period remain painfully relevant. First, we must recognize how economic incentives can transform violence from chaotic outbursts into systematic production—the commodification of death that occurred when scalps became currency has modern parallels in war profiteering and militarized borders. Second, we must remain vigilant about how intellectual frameworks can rationalize atrocity—the Judge's scientific collecting and philosophical justifications for dominance echo in contemporary arguments that dehumanize refugees or enemies. Finally, we must acknowledge that the violence of this period wasn't an aberration but foundational to modern nation-states—the borderlands weren't a lawless exception but rather the place where the true nature of conquest was most clearly revealed. Understanding this history doesn't provide easy answers, but it does demand that we confront the violence embedded in our institutions rather than projecting it safely into a distant past.

Best Quote

“Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.” ― Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian, or, the Evening Redness in the West

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights the novel's ability to serve a deeper purpose through its violence, comparing it to Melville's "Moby Dick" in its thematic execution. It praises "Blood Meridian" as one of the best novels despite its intense violence.\nWeaknesses: The review notes the gratuitous nature of the violence, which is described as mentally and emotionally exhausting, potentially alienating some readers, particularly women.\nOverall Sentiment: Enthusiastic\nKey Takeaway: Despite its overwhelming and gratuitous violence, "Blood Meridian" is lauded for its purposefulness in depicting brutality, aiming to immerse the reader in the desensitization experienced by its characters, thus elevating it to a high literary status.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.