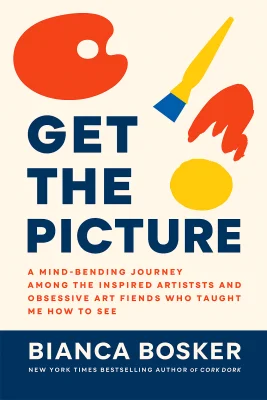

Get the Picture

A Mind-Bending Journey among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See

Categories

Nonfiction, Art, Biography, History, Memoir, Audiobook, Sociology, Biography Memoir, Contemporary, Art History

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2024

Publisher

Viking

Language

English

ASIN

0525562206

ISBN

0525562206

ISBN13

9780525562207

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Get the Picture Plot Summary

Introduction

I remember the first time I stood in front of a Jackson Pollock painting. While everyone around me nodded knowingly, I felt nothing but confusion. Those chaotic splatters that commanded millions at auction left me cold and questioning: What was I missing? Was there something wrong with me? This sense of exclusion from a world that seemed to speak a language I couldn't understand haunted me for years. Perhaps you've felt it too—that moment of standing before celebrated art and feeling utterly lost, wondering if you're the only one not getting the joke. The modern art world can feel like an exclusive club with invisible entry requirements, where insiders speak in code and outsiders are left to wander bewildered through sterile white galleries. But what if this disconnect isn't your fault? What if understanding art isn't about innate talent but about developing a particular way of seeing—one that can be learned, practiced, and ultimately mastered by anyone willing to embark on the journey?

Chapter 1: The White Cube: First Steps Into a Hidden World

The first time I visited a contemporary art gallery in Chelsea, I felt like I'd accidentally crashed a private party. The space was intimidatingly pristine—white walls, polished concrete floors, and not a descriptive label in sight. A gallery attendant with severe bangs and an all-black outfit barely acknowledged my presence as I tentatively approached what appeared to be a pile of dirty laundry arranged in the center of the room. Was this the art? Or had someone forgotten their gym clothes? "That's a Tina Schwarz piece," a voice behind me said. I turned to find a man in his sixties with architect glasses and a scarf that probably cost more than my monthly rent. "She's exploring the intersection of domesticity and labor politics. Brilliant, isn't it?" He didn't wait for my response before drifting away to examine what looked like an empty picture frame hanging on the wall. I nodded as if I understood, but inside I was panicking. Everyone else seemed to move through the space with confidence, speaking in hushed tones about "negative space" and "post-structuralist commentary." They knew the rules of this place, while I felt like an impostor about to be discovered and escorted out. Later that evening, I confessed my gallery anxiety to a friend who worked in the art world. She laughed and said, "The secret is that half the people there feel exactly like you do. They're just better at faking it." She explained that the art world thrives on exclusivity—the more people feel like outsiders looking in, the more special it feels to be an insider. "It's designed to be intimidating," she said. "That's part of how it maintains its mystique and value." This revelation was both comforting and disturbing. If the barriers to entry were partially artificial, constructed to keep people out rather than welcome them in, perhaps my confusion wasn't a personal failing but a predictable response to a system designed to confuse. The art world, I was beginning to understand, operates on unspoken rules and coded language. Learning to navigate it wouldn't just be about training my eye to appreciate different aesthetics—it would require decoding an entire social ecosystem with its own customs, hierarchies, and secret handshakes.

Chapter 2: The Language of Art: Decoding the Secret Code

During my first month of serious gallery-hopping, I started keeping a notebook of phrases I heard. "The work has a certain criticality," said one woman in oversized architectural eyewear. "I'm interested in his engagement with materiality," offered a man in a black turtleneck. At an opening in Brooklyn, I overheard someone describe a series of blank canvases as having "a compelling indexicality that references the absence of presence." I went home and googled "indexicality" only to fall down a rabbit hole of academic jargon that left me more confused than before. When I mentioned this to an art historian friend, she laughed. "That's International Art English," she explained. "It's a kind of specialized language that evolved from translated French theory in the 1970s. Most people using those terms don't fully understand them either." She showed me a study by Alix Rule and David Levine that analyzed thousands of press releases from galleries. They found that art writing often prioritizes sounding sophisticated over communicating clearly. Words like "space," "practice," and "interrogate" take on specialized meanings. Sentences grow convoluted, with multiple clauses and abstract nouns. The passive voice reigns supreme. "The viewer is confronted by the objecthood of representation," rather than "You'll see paintings of objects." This language serves multiple purposes. It creates an aura of intellectual depth, even around simple ideas. It signals membership in a cultural elite. Most importantly, it maintains ambiguity, allowing the same work to mean different things to different people without anyone being definitively wrong. I decided to experiment by incorporating some of this language into my own conversations. At a gallery opening, when someone asked what I thought about a video installation featuring a woman slowly eating a watermelon, I replied, "I'm struck by how it problematizes our relationship with consumption." The person nodded vigorously and launched into their own interpretation. I hadn't said anything substantive, but I'd used the right linguistic signals to be taken seriously. Learning this code wasn't just about fitting in—it revealed how language shapes perception. When we lack words to describe what we're seeing, we often fail to notice it at all. The specialized vocabulary of art criticism, for all its pretension, offers tools for articulating visual experiences that might otherwise remain invisible to us. The art world's secret language isn't just a barrier—it's also a bridge. Once you learn to translate it, you gain access not just to conversations but to new ways of seeing the world around you.

Chapter 3: Beauty and Disgust: The Paradox of Modern Aesthetics

"This is absolutely disgusting," the woman next to me whispered to her companion. We were standing in front of a large canvas covered in what appeared to be bodily fluids, food waste, and fragments of pornographic images. The piece was the centerpiece of a solo show by an artist whose previous work had sold for millions at auction. "That's the point," her friend replied. "It's supposed to make you uncomfortable. That's why it's important." This exchange captured a paradox I'd encountered repeatedly: in contemporary art circles, beauty is often treated with suspicion, while deliberate ugliness is celebrated as profound. Works that repel rather than attract are frequently praised as more "challenging" and "significant" than those that please the eye. I asked a curator about this during a museum tour. "Beauty became problematic in the 20th century," she explained. "After the horrors of the World Wars, many artists felt that creating beautiful objects was either a form of denial or a way of making suffering palatable. They turned to disruption and discomfort as more honest responses to a broken world." She pointed to a sculpture made of rusty metal and torn fabric. "This isn't meant to be hung over someone's sofa. It's meant to provoke thought about decay and impermanence. Beauty can be a kind of anesthetic that prevents us from seeing reality clearly." This perspective was illuminated further when I interviewed an artist whose installations featured industrial waste materials. "Beauty is easy," he told me. "Anyone can make something pretty. But making something that forces people to confront what they'd rather ignore—that's harder and more necessary." When I asked if he ever worried about alienating viewers, he shrugged. "If everyone likes your work, you're probably not saying anything important." I began to understand that for many contemporary artists, beauty isn't the goal but a tool—sometimes useful, sometimes distracting. The rejection of conventional beauty can be a political stance, a philosophical position, or simply a way to jolt viewers out of passive consumption into active engagement. Yet this approach creates its own contradictions. Work that was once shocking becomes familiar. Ugliness develops its own aesthetics. Museums and collectors pay millions for art that was intended to critique the very systems that now celebrate it. And ordinary viewers often feel excluded by work that seems deliberately inaccessible. The beauty paradox reveals a fundamental tension in how we experience art: between immediate sensory pleasure and intellectual challenge, between comfort and growth. Perhaps the most profound art finds ways to hold both possibilities open at once, neither surrendering to pure decoration nor rejecting the human need for visual connection.

Chapter 4: The Social Network: How Context Creates Value

At a dinner following a gallery opening in the Lower East Side, I found myself seated next to a collector who had just purchased a small painting for $45,000. The artist was barely out of graduate school, with only one previous show to her name. When I asked what had drawn him to her work, his answer surprised me. "Her professor at Yale was a protégé of Peter Schjeldahl, and she just got a residency at the same program where Julie Mehretu started. Plus, I heard the Whitney studio program is looking at her for next year." He hadn't mentioned a single thing about the painting itself—its colors, composition, or subject matter. This conversation illuminated something I'd been slowly realizing: in the art world, context often matters more than content. Who an artist knows, where they studied, who collects their work, and which institutions show it can determine value more than the intrinsic qualities of the artwork itself. I witnessed this principle in action at an auction preview, where two nearly identical works by the same artist were estimated at dramatically different prices. The difference? One had been owned by a famous collector and exhibited at MoMA; the other had spent decades in a private home with no exhibition history. The provenance—the social life of the object—had become inseparable from its value. A gallery director explained it to me this way: "Art doesn't exist in a vacuum. Its meaning and value are socially constructed through a network of relationships and institutions. That painting isn't just pigment on canvas—it's a node in a complex web of cultural capital." This context game extends to viewers as well. How we experience art depends heavily on where we encounter it and what we know about it. The same object displayed in a dumpster might be ignored, while in a prestigious museum it commands reverent attention. A painting described as the work of an established master receives different scrutiny than one attributed to an unknown artist. A study I read confirmed this effect: researchers showed the same artworks to different groups, providing some with information about the artist's prestigious background and others with no context. Those who received the contextual information not only rated the work more highly but literally saw it differently, spending more time examining details and reporting stronger emotional responses. The context game reveals that art is never just about the relationship between a viewer and an object—it's about our relationship to an entire ecosystem of meaning-making. This doesn't invalidate personal responses, but it does complicate the idea that we can ever see art with truly fresh eyes, unmediated by social influences.

Chapter 5: The Artist's Eye: Learning to See Like a Creator

"Don't move," Julie instructed, her brush poised mid-air. I was sitting for a portrait in her Brooklyn studio, trying desperately to maintain my pose while fighting an itch on my nose. The late afternoon light streamed through the industrial windows, illuminating dust particles that danced around us like miniature constellations. Julie worked in silence for long stretches, occasionally muttering to herself or stepping back to squint at her canvas. I watched her watching me—the way her eyes darted between my face and her painting, how she measured proportions with her thumb, how she mixed colors with mathematical precision. Occasionally she would become frustrated, scraping away entire sections with a palette knife and starting again. "The problem isn't getting it to look like you," she explained during a break. "The problem is deciding which version of you to capture. There are thousands of possible portraits here. I have to choose one." This insight—that seeing isn't passive reception but active selection—transformed my understanding of how artists work. Over the following months, I visited dozens of studios, watching artists in different mediums engage with their materials. A sculptor showed me how she walks around her work in progress, experiencing it from multiple angles before deciding where to add or subtract. A photographer explained how he might take hundreds of nearly identical shots, looking for the one where the light reveals exactly what he wants to emphasize. What became clear was that artists don't simply have better technical skills—they have developed specific ways of looking. They notice relationships between shapes, subtle variations in color, the emotional impact of different compositions. Most importantly, they make conscious choices about what to emphasize and what to ignore. A painter working with urban landscapes showed me his reference photos alongside his finished canvases. The paintings weren't exact reproductions—they amplified certain elements while minimizing others. "I'm not documenting what's there," he said. "I'm showing you what I see when I look at it. The feeling of the place, not just its appearance." This selective vision isn't limited to creating art—it's fundamental to experiencing it as well. When we look at artwork, we're not passive recipients but active participants, bringing our own selective attention to bear on what we see. The difference is that most of us make these selections unconsciously, while artists have learned to make them deliberately. By watching artists work, I began to understand that developing an "eye" for art isn't about acquiring some mystical sensitivity. It's about learning to look with intention—to notice what you notice, to question why certain elements draw your attention while others recede, and to recognize the choices embedded in every image you encounter.

Chapter 6: The Business of Beauty: Art Fairs and Market Forces

The convention center sprawled across several city blocks, its interior transformed into a labyrinth of temporary walls creating hundreds of miniature galleries. Art Basel Miami Beach—the most prestigious art fair in North America—was a sensory assault: thousands of artworks competing for attention, celebrities posing for photos, collectors in designer clothing speaking urgently into their phones, and the constant buzz of commerce disguised as cultural appreciation. "That sold within the first ten minutes of the VIP preview," a gallery assistant told me, nodding toward an empty spot on the wall where a small red dot indicated a sale. "We had three collectors fighting over it." The piece, a modestly sized painting by an emerging artist, had sold for $85,000. By the end of the day, the gallery had sold over $2 million in artwork. Behind the glamorous facade, I discovered the machinery of the art market operating at its most efficient. Galleries paid upwards of $50,000 for their booths, not including shipping, insurance, travel, and entertainment expenses. To recoup these costs, they brought their most commercial work—pieces designed to appeal to collectors making quick decisions in an overstimulated environment. "Art fairs are terrible places to actually look at art," admitted a dealer from Berlin. "The lighting is bad, there's no space for contemplation, and everything is reduced to a commodity. But this is where the money is, so we all show up." The economics were revealing. While museums and non-profit spaces might champion experimental or challenging work, the commercial art world operates on different principles. Galleries function as small businesses with high overhead costs. They need to sell work to survive, which inevitably influences what gets shown and promoted. I shadowed an art advisor as she guided wealthy clients through the fair. "They're looking for blue-chip names they recognize, or emerging artists who might be good investments," she explained. "Most collectors want work that's challenging enough to seem important but accessible enough to live with. And increasingly, they want something that photographs well for Instagram." At a party on a hotel rooftop that evening, I met a collector who had spent over $300,000 at the fair that day. When I asked what drew him to the pieces he'd purchased, he was refreshingly candid: "Some of it is aesthetic—I buy what I respond to. But I also consider the artist's career trajectory, which institutions are showing their work, and yes, potential appreciation in value. Anyone who tells you they're not thinking about the investment aspect is probably lying." This commercial reality doesn't invalidate the artistic significance of the work being sold, but it does shape what gets made, shown, and celebrated. The market rewards certain types of art—work that is visually striking, conceptually accessible, and aligned with current trends. Artists who want sustainable careers must navigate these pressures while maintaining their creative integrity. The Miami machine revealed the art world as an ecosystem where aesthetic, intellectual, and commercial concerns are inextricably linked. Understanding this doesn't diminish the power of art, but it does demystify how certain works come to prominence while others remain in obscurity.

Chapter 7: Finding Your Vision: Personal Transformation Through Art

The performance was scheduled to begin at 7 PM in a former warehouse in Bushwick. I arrived early, nervous about what I was about to experience. The artist, known for physically demanding works that tested the boundaries between performer and audience, had a reputation for creating situations that were deliberately uncomfortable. The space was empty except for a circle of chairs facing inward. As other viewers arrived, we took our seats, exchanging awkward glances. At precisely 7, the artist entered, dressed in ordinary clothes, and sat in the remaining chair. Without introduction, she began to weep—not theatrical sobbing, but the quiet, body-shaking tears of genuine grief. Minutes passed. The crying continued. The audience shifted uncomfortably. Was this the entire performance? Should we do something? Say something? Leave? The atmosphere grew increasingly tense as the artist's vulnerability confronted our voyeurism. After twenty excruciating minutes, she stopped crying, looked each of us in the eye, and left the room. Six months earlier, I would have dismissed this experience as pretentious nonsense. But something had changed in me. Instead of intellectualizing or judging, I allowed myself to feel the discomfort fully—the empathic response to another's pain, the ethical questions about witnessing suffering as entertainment, the uncertainty about how to respond appropriately. On the subway home, I realized this performance had affected me more deeply than many conventionally beautiful artworks I'd seen. It had created a space for reflection about human connection, social norms, and emotional authenticity that lingered long after the experience itself. This was the culmination of a gradual transformation in how I engaged with art. I had begun to develop what insiders call an "eye"—not just the ability to recognize quality or importance according to established criteria, but a personal way of seeing that connected visual experience to meaning. My eye wasn't the same as the collectors' eyes I'd observed, which often focused on investment potential and status. It wasn't identical to critics' eyes, which placed works within historical and theoretical contexts. It was uniquely mine—informed by everything I'd learned but ultimately guided by my own sensibilities and concerns. I no longer needed someone else to tell me what was good or important. I could stand before a work and ask: Does this move me? Challenge me? Make me see something differently? The answers might not align with market values or critical consensus, but they were authentic to my experience. This didn't mean I suddenly appreciated everything. Some work still left me cold, confused, or irritated. But I had developed the confidence to engage with art on my own terms, neither dismissing what I didn't immediately understand nor accepting others' judgments without question. The greatest revelation was discovering that developing an eye isn't about acquiring specialized knowledge—though that helps—but about learning to trust your own perceptions while remaining open to having them transformed. It's about cultivating attention rather than passive consumption, curiosity rather than certainty, and personal connection rather than abstract appreciation.

Summary

The journey through the modern art world reveals that seeing is not a passive act but an active practice—one that can be developed, refined, and transformed. What appears at first as an impenetrable fortress of insider knowledge and coded language gradually emerges as a landscape of possibility, where confusion and discomfort become pathways to deeper understanding rather than barriers to entry. The art world's contradictions—its simultaneous embrace of beauty and ugliness, commerce and critique, exclusivity and revelation—mirror our own complex relationship with visual experience. Perhaps the most valuable insight from this exploration is that developing an "eye" for art isn't about conforming to established taste or memorizing art historical references. It's about cultivating your own unique way of seeing—one that incorporates knowledge but remains rooted in personal experience. It means learning to notice what you notice, to question why certain works affect you while others don't, and to recognize that meaningful engagement with art often begins precisely at the point where comfort ends. The reward for this effort isn't just a greater appreciation of what hangs on gallery walls, but a richer perception of the visual world in all its dimensions—a way of seeing that transforms not just how we look at art, but how we experience everything around us.

Best Quote

“Art is a choice. It is a fight against complacency. It is a decision to forge a life that’s richer, more uncomfortable, more mind-blowing, more uncertain. And ultimately, more beautiful.” ― Bianca Bosker, Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See

Review Summary

Strengths: The book offers a unique and engaging exploration of the art world through Bianca Bosker's immersive experiences. Her approach as a neophyte provides fresh and candid insights into various art environments such as galleries, fairs, studios, and museums. The narrative is both insightful and unpretentious, offering an authentic perspective on the art scene.\nWeaknesses: The introduction's tone, emphasizing the author's ignorance, initially tests the reader's patience. However, this issue resolves as the narrative progresses.\nOverall Sentiment: Enthusiastic\nKey Takeaway: "Get the Picture" is a compelling and insightful journey through the art world, enriched by Bosker's immersive and candid approach, which offers readers a fresh perspective on artists, gallerists, and collectors.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.