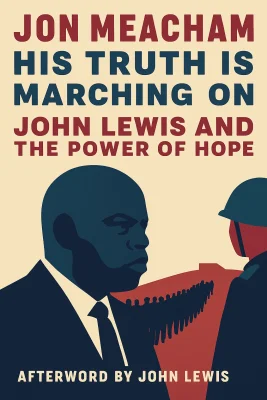

His Truth Is Marching On

John Lewis and the Power of Hope

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Memoir, Politics, Audiobook, Social Justice, Biography Memoir, American History, Race

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2020

Publisher

Random House

Language

English

ISBN13

9781984855022

File Download

PDF | EPUB

His Truth Is Marching On Plot Summary

Introduction

On a sweltering Sunday afternoon in March 1965, a young man named John Lewis stood at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Facing a wall of state troopers armed with nightsticks and tear gas, the 25-year-old civil rights activist knew what was coming. He had been beaten before for challenging segregation, yet he walked forward with quiet determination, leading hundreds in a peaceful march for voting rights. What followed was a brutal attack that would become known as "Bloody Sunday" - a pivotal moment that shocked the nation's conscience and helped secure passage of the Voting Rights Act. In that moment of extraordinary courage, Lewis embodied what he called "soul force" - the spiritual power of nonviolent resistance in the face of violent oppression. John Lewis's journey from the son of Alabama sharecroppers to civil rights icon and respected congressman represents one of the most remarkable American lives of the 20th century. His story illuminates the transformative power of nonviolent resistance, the importance of moral courage in the face of injustice, and the capacity of ordinary individuals to create extraordinary change. Through Lewis's experiences - from preaching to chickens as a child to facing down brutal violence during the Freedom Rides, from the triumphs of the civil rights movement to his decades of service in Congress - we witness not only the struggle for racial equality in America but also the triumph of what Martin Luther King Jr. called "the strength to love" in the face of hatred and violence.

Chapter 1: Early Years: Seeds of Courage in the Jim Crow South

John Robert Lewis was born on February 21, 1940, in a small shotgun shack outside Troy, Alabama. His parents, Eddie and Willie Mae Lewis, were sharecroppers who worked land owned by white farmers, trapped in a system of economic servitude that had replaced slavery throughout much of the South. For the Lewis family, like most Black families in the Jim Crow South, life was defined by hard physical labor and strict racial boundaries. From his earliest memories, John was aware of the signs designating "WHITE" and "COLORED" facilities, the visible manifestation of a system designed to reinforce racial hierarchy. Despite these harsh realities, the Lewis household was filled with love and values that would shape John's character. His parents emphasized honesty, hard work, and respect for others. Though they cautioned their children to accept the world as it was, not to "get in trouble" by challenging segregation, they also instilled a sense of dignity that transcended their circumstances. John would later recall his mother's hands - fingers split and hardened from years in the cotton fields - as a powerful symbol of both suffering and strength that motivated his quest for justice. Religion became young John's first avenue of expression and resistance. Given a Bible at age four, he was drawn to the sweeping biblical narratives of exile and deliverance, fall and resurrection. By age five, he was preaching to the family's chickens in the yard, conducting elaborate services and even funerals when one died. This peculiar childhood practice became a formative experience - Lewis later reflected that caring for those chickens taught him about "discipline and responsibility, and, of course, patience." His congregation of chickens was unruly but attentive, preparing him for a lifetime of speaking difficult truths to unreceptive audiences. The turning point in Lewis's young life came when he first heard Martin Luther King Jr. on the radio in 1955. King was delivering a sermon called "Paul's Letter to American Christians," speaking about the moral imperative to fight segregation. "When I heard King," Lewis recalled, "it was as though a light turned on in my heart. When I heard his voice, I felt he was talking directly to me." King's message - that Christianity demanded social justice in this world, not just salvation in the next - resonated deeply with Lewis. Here was a vision of faith that addressed the injustices he had witnessed his entire life. In 1957, at seventeen, Lewis left Troy for American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee. With just $100 from his uncle, a footlocker of clothes, and his Bible, he boarded a Greyhound bus heading north. His parents worried but supported his decision. They couldn't know that their son was embarking on a journey that would not only transform his life but help change the course of American history. In Nashville, Lewis would find his voice and his calling in the emerging civil rights movement, beginning a lifelong commitment to what he called "good trouble" - necessary disruption in the service of justice.

Chapter 2: Nashville Movement: The Discipline of Nonviolence

Nashville proved transformative for John Lewis. At American Baptist Theological Seminary (known as "the Holy Hill"), he found intellectual stimulation and a community of like-minded students. Though the campus was modest - just a few redbrick buildings overlooking the Cumberland River - it became the crucible where Lewis's nascent sense of justice was forged into a lifelong commitment. His professors introduced him to philosophical concepts that resonated deeply, particularly Hegel's dialectic of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. "Segregation is a thesis," one professor explained. "Its antithesis would be the struggle to destroy segregation. Out of that struggle would come the synthesis: integration." The most significant influence on Lewis's development came from Reverend James Lawson, a Methodist minister who had studied Gandhian nonviolence in India. In the fall of 1958, Lewis began attending Lawson's workshops on nonviolent resistance held in the basement of Clark Memorial Methodist Church. These Tuesday night sessions blended Christian theology with practical training for confronting segregation. Lawson taught that nonviolence was not merely a tactic but a way of life - a philosophy rooted in love for one's opponents. "He showed us how to curl our bodies so that our internal organs would escape direct blows," Lewis recalled. "But it was not enough to simply endure a beating. It was not enough to resist the urge to strike back at an assailant. 'That urge can't be there,' he would tell us." Lewis embraced this philosophy with remarkable thoroughness. While many found nonviolence difficult to practice, Lewis seemed naturally suited to it. "He was marked because John Lewis, as I remember him, had no questions," Lawson later recalled. "The ideas grabbed him, and he grabbed the ideas." The workshops included role-playing exercises where students practiced maintaining dignity and composure while being insulted, spat upon, or struck. They studied Thoreau, Gandhi, and Reinhold Niebuhr, developing both a theoretical framework and practical skills for confronting injustice without violence. In February 1960, Lewis and other Nashville students put their training into action. Inspired by a sit-in at a Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, they launched their own campaign to desegregate Nashville's downtown stores. Dressed in their Sunday best, they sat quietly at whites-only lunch counters, asking for service. When refused, they remained seated, often studying or reading. On February 27, white toughs attacked the demonstrators, punching them and burning them with cigarettes. Lewis was knocked to the floor but never fought back. Police arrested the students - not their attackers - for "disorderly conduct." In jail, Lewis experienced what he called a threshold moment: "That paddy wagon seemed like a chariot to me, a freedom vehicle carrying me across a threshold... I had stepped through the door into total, unquestioning commitment." Rather than pay bail, the students chose to remain in jail, singing freedom songs and chanting "Jail without bail!" Their disciplined response to violence and willingness to suffer for justice began attracting national attention. When Nashville's mayor, Ben West, finally conceded that lunch counters should be desegregated, it marked a significant victory for nonviolent direct action. By 1961, Lewis had become a recognized leader in the student movement. He was elected chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an organization formed to coordinate student activism across the South. Despite his youth and soft-spoken manner, Lewis possessed an inner strength that commanded respect. "He had a remarkable degree of toughness, of inner courage, of commitment," recalled fellow activist Diane Nash. "I always had the impression that he was just never going to let anybody turn him around." This quiet determination would soon be tested in ways that would shock the nation's conscience.

Chapter 3: Freedom Rides: Facing Violence with Disciplined Love

In May 1961, John Lewis embarked on what would become one of the most dangerous chapters of his life - the Freedom Rides. These integrated bus journeys through the Deep South were designed to test compliance with Supreme Court decisions that had outlawed segregation in interstate transportation facilities. When Lewis read about the planned rides in a newsletter, he immediately applied to join, writing: "This is the most important decision in my life, to decide to give up all if necessary for the Freedom Ride, that Justice and Freedom might come to the Deep South." The journey began in Washington, D.C., on May 4, 1961. Lewis and twelve other riders - Black and white, male and female - boarded Greyhound and Trailways buses bound for New Orleans. The first real violence erupted in Rock Hill, South Carolina, where Lewis and his white seatmate, Albert Bigelow, attempted to enter a whites-only waiting room. A group of young white men attacked them, repeatedly striking Lewis in the face and kicking him as he fell. With blood in his mouth and pain stabbing above both eyes, Lewis refused to press charges, telling police, "We're not here to cause trouble. We're here so that people will love each other." The violence escalated dramatically as the Freedom Riders entered Alabama. On Mother's Day, May 14, a mob in Anniston firebombed one of the buses and attacked the passengers as they fled the flames. When Lewis and a second group of riders reached Birmingham, they were met by another brutal mob. The city's notorious public safety commissioner, Bull Connor, allowed the attackers fifteen minutes of uninterrupted violence before police intervened. Despite these horrors, Lewis and fellow Nashville student Diane Nash were determined the rides must continue. When the original CORE-sponsored Freedom Ride was suspended, they organized reinforcements. On May 20, Lewis and the new group of Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery, Alabama. As they stepped off the bus, they were ambushed by a mob of thousands wielding baseball bats, pipes, and chains. Lewis was struck on the head with a wooden Coca-Cola crate and knocked unconscious. "I could feel my knees collapsing and then nothing," he recalled. "Everything turned white for an instant, then black." When he regained consciousness, blood was pouring from the back of his head. The riders found refuge in a Black church, which was subsequently surrounded by an angry white mob throughout the night. Undeterred, Lewis and the other Freedom Riders pressed on to Jackson, Mississippi. Upon arrival, Lewis was immediately arrested for using a whites-only restroom. He was sentenced to sixty days in Mississippi's notorious Parchman Farm penitentiary. The conditions were brutal - prisoners were stripped naked, blasted with fire hoses, and subjected to psychological torture. "Parchman was not a blessed place," Lewis later said. Yet even there, the Freedom Riders maintained their dignity, organizing classes, singing freedom songs, and strengthening their commitment to nonviolence. The Freedom Rides succeeded in forcing federal action. Attorney General Robert Kennedy petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to issue clear regulations prohibiting segregation in interstate travel facilities, which took effect in November 1961. More importantly, the rides demonstrated the power of what Lewis called "soul force" - the capacity to transform hatred through love and suffering. "We grew tougher, we grew wiser," Lewis said of his time in Parchman. "We became better souls, more committed to the way of peace and the way of love."

Chapter 4: Selma and Beyond: Leading at the Crossroads of History

By early 1965, John Lewis had already established himself as a veteran of the civil rights movement. As chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, he had endured beatings, arrests, and imprisonment across the South. But the events in Selma, Alabama, would elevate him to a place in American history that few could have anticipated. Selma had become a focal point in the struggle for voting rights. Despite the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which had outlawed segregation in public accommodations, Black citizens in much of the South remained effectively disenfranchised through discriminatory registration practices, intimidation, and violence. On Sunday, March 7, 1965, Lewis and Hosea Williams led approximately 600 marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, intending to walk from Selma to Montgomery to petition Governor George Wallace for voting rights. At the end of the bridge, they were met by a wall of state troopers and mounted sheriff's deputies. When the marchers refused to turn back, the officers attacked with nightsticks, tear gas, and bullwhips. Lewis, walking at the front of the line, suffered a fractured skull when a trooper struck him with a billy club. "I thought I was going to die," Lewis later recalled. "I thought I saw death." The violence was captured by television cameras, and images of what became known as "Bloody Sunday" were broadcast into living rooms across America that evening. The nation watched in horror as peaceful demonstrators were brutally beaten on U.S. soil. The shocking footage created a groundswell of public support for the voting rights movement. Eight days after Bloody Sunday, President Lyndon B. Johnson addressed a joint session of Congress, calling for comprehensive voting rights legislation. In his speech, Johnson adopted the movement's anthem, declaring, "We shall overcome." The Voting Rights Act, signed into law on August 6, 1965, would become one of the most effective civil rights laws in American history, dramatically increasing Black voter registration throughout the South. For Lewis, Selma represented both the nadir of violence against the movement and its greatest legislative triumph. The Edmund Pettus Bridge became a powerful symbol of the struggle and sacrifice required to advance democracy. "Selma, the bridge, was a test of the belief that love was stronger than hate," Lewis reflected. "And it is. Much stronger." The victory at Selma, however, came at a personal cost for Lewis. The SNCC he led was becoming increasingly divided over strategy and philosophy. Some members questioned the continued commitment to nonviolence and integration, advocating instead for Black Power and self-defense. In 1966, Lewis was ousted as chairman, replaced by Stokely Carmichael, who represented the more militant wing of the organization. This transition reflected broader tensions within the civil rights movement as it entered a new phase following the legislative victories of 1964 and 1965. Despite this setback, Lewis remained steadfast in his belief in nonviolent resistance and the vision of the "Beloved Community" - a society based on justice, equal opportunity, and love for one's fellow human beings. While others in the movement became disillusioned or radicalized, Lewis maintained his faith in the possibility of redemptive transformation through nonviolent action. This unwavering commitment would define his approach to social change for the rest of his life, carrying him from the frontlines of protest to the halls of Congress, where he would continue the struggle for justice in a different arena.

Chapter 5: The Beloved Community: Lewis's Enduring Vision

At the heart of John Lewis's lifelong commitment to social justice was his vision of the "Beloved Community" - a concept he embraced from his mentor, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. For Lewis, this wasn't merely a political ideal but a spiritual imperative that guided his every action. The Beloved Community represented a society based on justice, equal opportunity, and love for fellow human beings, where poverty, hunger, and hate would be replaced with peace, justice, and brotherhood. This vision transcended conventional political categories, offering a moral framework for addressing the deepest divisions in American society. Lewis's conception of the Beloved Community was deeply rooted in his religious faith. Growing up in the rural church tradition of Alabama, he absorbed the Christian teachings of universal love and human dignity. Later, through his theological studies and the workshops led by James Lawson, he integrated these beliefs with Gandhian principles of nonviolence and the social gospel tradition. The result was a worldview that saw love as the most powerful force for social transformation. "I believe in the way of peace, in the way of love, in the way of nonviolence," Lewis often said. "I believe that we all are one family." Central to Lewis's understanding of the Beloved Community was the concept of reconciliation. He did not view the civil rights movement as a battle against white people but as a struggle against the system of segregation that dehumanized both the oppressed and the oppressor. His goal was not victory over his opponents but conversion and redemption. This was dramatically illustrated when, decades after being beaten in Rock Hill, South Carolina, Lewis met and forgave one of his attackers, Elwin Wilson, who had sought him out to apologize. Their reconciliation, captured on national television, demonstrated the transformative power of forgiveness that Lewis had always advocated. The path to the Beloved Community, according to Lewis, required what he called "good trouble" - the willingness to disrupt unjust systems through nonviolent direct action. This approach demanded tremendous courage and discipline. It meant facing violence without returning it, absorbing hatred without becoming hateful, and maintaining faith in the possibility of transformation even when evidence suggested otherwise. For Lewis, this was not passive resistance but active, creative, and redemptive love. "You have to be persistent," he explained. "You have to be determined. You have to have faith. You have to be hopeful." Throughout his life, Lewis remained remarkably consistent in his commitment to this vision, even as the political landscape changed around him. When the movement fractured in the late 1960s, with some activists embracing Black Power and others advocating more conventional political strategies, Lewis maintained his belief in the power of nonviolence and reconciliation. "Violence is not the way," he insisted, even when such sentiments were no longer fashionable in activist circles. This steadfastness reflected not rigidity but a profound moral clarity that transcended shifting political winds. What distinguished Lewis's vision from mere idealism was his practical commitment to embodying these principles in concrete action. From the Nashville sit-ins to the Freedom Rides, from Selma to his later work in Congress, he consistently demonstrated the courage to put his body on the line for his beliefs. The Beloved Community was not an abstract utopia for Lewis but a practical goal toward which every nonviolent action moved the nation closer. His life became a testament to the power of this vision to inspire genuine social transformation, offering a model of moral leadership that remains vitally relevant in an age of increasing polarization and conflict.

Chapter 6: From Protest to Politics: The Conscience of Congress

After the high-water mark of the civil rights movement in the mid-1960s, John Lewis faced the challenge of translating the moral force of protest into lasting political change. The passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 had removed many barriers to Black political participation, creating new opportunities for representation. For Lewis, this shift from "protest to politics" represented not an abandonment of his principles but their application in a different arena. "Sometimes you have to not just dream about what could be," he would later say, "you have to get out and push, and you have to stand up, and you have to speak out." The transition was not immediate. After being ousted as chairman of SNCC in 1966, Lewis experienced a period of soul-searching. He worked for the Field Foundation and the Southern Regional Council, organizations dedicated to voter education and community development. During this time, he completed his bachelor's degree at Fisk University and married Lillian Miles, a librarian and educator who would become his closest advisor and partner in the decades ahead. Their partnership provided Lewis with both personal happiness and intellectual companionship as he navigated the evolving landscape of American politics. Lewis's entry into electoral politics came in 1981, when he won a seat on the Atlanta City Council. This local position allowed him to address concrete issues affecting urban communities - housing, transportation, public safety - while building a political base. His approach to governance reflected the same moral clarity that had characterized his activism. He refused to engage in the cynical deal-making that often defined local politics, instead advocating consistently for the disadvantaged and marginalized. "You cannot be afraid to speak up and speak out for what you believe," he maintained. "You have to have courage, raw courage." In 1986, Lewis decided to run for Congress, challenging his former SNCC colleague Julian Bond for Georgia's 5th Congressional District seat. The campaign was difficult and at times bitter, pitting two civil rights icons against each other. Lewis, less polished but widely respected for his moral authority and sacrifice, won the Democratic primary and then the general election. He would go on to represent the district for more than three decades, becoming known as the "conscience of the Congress." His presence in the House of Representatives served as a living link to the civil rights movement, reminding his colleagues and the nation of the moral imperatives that had driven that struggle. As a congressman, Lewis approached legislation through the lens of his longstanding commitment to the Beloved Community. He championed voting rights, healthcare access, education, and poverty reduction. He was an early and consistent advocate for LGBTQ rights, even when such positions carried political risks. His moral credibility gave him unusual influence among his colleagues, who recognized that his positions were rooted not in political calculation but in deep conviction. When Lewis spoke on the House floor, members from both parties listened with respect, acknowledging the moral authority he had earned through sacrifice and consistency. Lewis never abandoned direct action even while serving in Congress. He was arrested multiple times for participating in protests against apartheid in South Africa, genocide in Darfur, and for immigration reform. In 2016, he led a sit-in on the House floor to demand action on gun violence following the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando. "Sometimes you have to get in the way," he explained. "You have to make some noise by speaking up and speaking out against injustice and inaction." This willingness to engage in civil disobedience while holding elected office demonstrated Lewis's understanding that democratic progress requires both institutional engagement and moral witness.

Chapter 7: Legacy of Faith: The Spiritual Foundations of Moral Leadership

John Lewis's extraordinary moral leadership was inseparable from his deep spiritual foundations. From his childhood practice of preaching to chickens on his family's farm to his final days as the "conscience of Congress," faith remained the wellspring of his courage and conviction. His religious understanding was not merely personal but profoundly social, connecting individual transformation with collective liberation. "Faith is being so sure of what the spirit has whispered in your heart that your belief in its eventuality is unshakable," Lewis wrote. This faith sustained him through beatings, imprisonment, and political setbacks, providing a source of resilience that amazed even his closest associates. Lewis's spirituality was rooted in the Black church tradition, with its emphasis on dignity, freedom, and justice. Growing up in rural Alabama, he absorbed the rhythms and rhetoric of Baptist preaching, the power of spirituals, and the biblical narratives of exodus and deliverance. These elements formed the bedrock of his worldview and provided him with a language to articulate his vision of social change. When he spoke of the "Beloved Community," he was drawing on a religious conception of human fellowship that transcended political categories. His understanding of nonviolence was similarly grounded in spiritual principles, particularly Jesus's teachings about loving one's enemies and turning the other cheek. What set Lewis apart was his ability to translate spiritual principles into nonviolent action. He understood that faith without works was empty, that love required courage, and that redemption demanded sacrifice. The concept of "redemptive suffering" - the idea that unearned suffering could be transformative both for the sufferer and the broader society - became central to his approach. When beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, he viewed his pain not as meaningless but as part of a larger spiritual drama of America's redemption. This perspective enabled him to maintain dignity and purpose even in the most dehumanizing circumstances. Lewis's faith gave him remarkable resilience in the face of violence and setbacks. After being attacked during the Freedom Rides, he refused to press charges or seek revenge. Instead, he maintained what he called "the discipline of nonviolence," responding to hatred with love and to injury with forgiveness. This approach was not passive but profoundly active, requiring tremendous spiritual strength. "You have to have the capacity to see beyond the moment," he explained. "You have to believe that the universe is on the side of justice." This conviction allowed him to persist when others might have surrendered to despair or cynicism. Throughout his life, Lewis maintained an unusual consistency between his religious beliefs and his public actions. Unlike many political figures who compartmentalize their faith, he integrated his spiritual and political commitments. This integration gave his leadership a rare authenticity. Whether addressing a church congregation or speaking on the House floor, he communicated the same fundamental message about human dignity and the moral imperative of justice. "When you pray, move your feet," he often said, quoting an African proverb that captured his understanding of the relationship between faith and action. Lewis's spiritual vision extended beyond conventional religious boundaries. While firmly rooted in Christianity, he embraced what he saw as universal principles of love and justice that could unite people across different faith traditions and philosophical perspectives. His concept of the "Spirit of History" - a force larger than any individual that moves through human events toward justice - reflected this expansive understanding. It allowed him to collaborate with people of diverse backgrounds while maintaining his own spiritual center. This inclusive approach made him an effective bridge-builder in an increasingly pluralistic society.

Summary

John Lewis's life embodied a profound paradox: in surrendering to violence without returning it, he discovered an unstoppable power. His journey from a sharecropper's son preaching to chickens to a civil rights icon and respected congressman demonstrates how moral courage can transform both individuals and nations. Lewis's greatest gift to America was his unwavering belief in what he called "the Spirit of History" - a force that moves inexorably toward justice when ordinary people make extraordinary commitments to nonviolence, reconciliation, and love. The essence of Lewis's legacy is captured in his concept of "good trouble" - the willingness to disturb the comfortable, to challenge unjust systems, and to accept suffering rather than inflict it. In an age of increasing polarization and political cynicism, his example offers a different path forward. Lewis showed that effective change requires not just righteous anger but disciplined love; not just critique but constructive engagement; not just resistance but reconciliation. For anyone seeking to create meaningful change in their communities or in the world, John Lewis's life offers this enduring lesson: true power lies not in domination but in the courage to stand unarmed for truth, to absorb hatred without returning it, and to maintain faith that justice will ultimately prevail.

Best Quote

“Destiny is not a matter of chance; it is a matter of choice. It is not a thing to be waited for; it is a thing to be achieved.” ― Jon Meacham, His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope

Review Summary

Strengths: The review praises Jon Meacham's ability to vividly bring John Lewis's story and the civil rights movement to life, highlighting Lewis's integrity, faith, and peaceful activism. It appreciates the inclusion of Lewis's own words, which are described as impressive and unforgettable. The book is characterized as a beautiful tribute to one of the civil rights movement's greatest figures.\nOverall Sentiment: Enthusiastic\nKey Takeaway: The review emphasizes the importance of John Lewis's legacy and the compelling manner in which Jon Meacham captures his life and contributions to the civil rights movement, portraying Lewis as a figure of integrity and hope in a time where such qualities are needed.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.