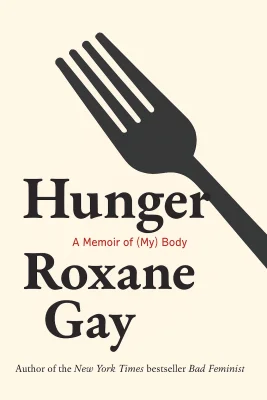

Hunger

A Memoir of (My) Body

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, Memoir, Mental Health, Audiobook, Feminism, Essays, Biography Memoir, Book Club, LGBT

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2017

Publisher

HarperCollins

Language

English

ASIN

0062362593

ISBN

0062362593

ISBN13

9780062362599

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Hunger Plot Summary

Introduction

In Roxane Gay's searing memoir, we encounter a powerful testimony of what it means to live in a body that society often deems unacceptable. With raw honesty and unflinching courage, Gay invites readers into the most intimate spaces of her life, exploring the complex relationship between her physical self and the traumatic experience that reshaped it. This is not a triumphant weight-loss narrative or a story of body acceptance that ends in neat resolution. Rather, it is a genuine examination of hunger in all its forms—hunger for food, for acceptance, for protection, for understanding, and ultimately, for the right to exist without apology. Through Gay's journey, readers gain insight into three profound aspects of human experience: how trauma can rewrite our relationship with our physical selves, how society's treatment of unruly bodies inflicts daily wounds on those who inhabit them, and how the path toward healing requires confronting painful truths about both ourselves and the world we navigate. Her account challenges us to reconsider our assumptions about bodies, weight, trauma, and healing, while offering a deeply human perspective on what it means to be vulnerable in a world that often demands invulnerability.

Chapter 1: Childhood: The Girl Before the Woods

Roxane Gay begins by describing her early childhood through the lens of family photographs, artifacts that captured a time when she was a happy, carefree child. Born in Omaha to Haitian American parents—her father a civil engineer and her mother a homemaker—young Roxane was documented extensively in family albums. Her mother meticulously archived these memories, recording milestones and achievements with the dedication of someone who understood the importance of preserving history. In these earliest pictures, Gay appears as a joyful baby, the center of her parents' world, their faces consistently beaming with pride and love. She describes herself as a child who loved books and writing, who would draw little villages on napkins and create stories about the people who lived there. Her imagination was her sanctuary, a place where she could create worlds and inhabit them fully. The Little House on the Prairie series became her favorite, along with works by Judy Blume and adventures about girls mining for gold in California. Family life revolved around the dinner table, where her parents, brother Joel (born when she was three), and later Michael Jr. created an intimate island of connection. Gay remembers these meals as more than just nourishment—they were moments of belonging, of being seen and valued. Her mother prepared healthy, well-rounded meals, sometimes American dishes from Betty Crocker cookbooks, sometimes Haitian cuisine—everything made from scratch as expressions of affection. As a child, Gay was enrolled in various sports—soccer, softball, basketball—though she admits she rarely excelled at them. The one exception was swimming, where she felt free, capable and strong in the water. What she lacked in athletic prowess, she made up for in academic achievement. Excellence was expected, and she delivered, though her true passion remained books and writing and daydreaming. These early years stand in stark contrast to what would come later. Gay frequently refers to the "before" and "after" of her life—the dividing line being a violent incident that would transform her relationship with her body forever. In the photographs from her childhood, she notes, "I get older. I smile less." The happy, whole child gradually disappears from the frame, replaced by someone hollow, someone hiding. The foundation of security and belonging established in her early years would be profoundly shaken, setting the stage for a lifelong struggle to reclaim that sense of safety.

Chapter 2: The Breaking Point: Trauma and Its Aftermath

At twelve years old, Roxane Gay experienced a trauma that would become the fault line in her life, dividing everything into "before" and "after." While riding bikes with a boy she thought she loved, Christopher, they stopped at an abandoned hunting cabin in the woods. There, he and several of his friends gang-raped her in an act of devastating violence. She describes this experience with careful, measured language, providing just enough detail to convey the horror without sensationalizing it. "I was twelve years old," she writes with devastating simplicity, "and suddenly, I was no longer a child." The aftermath was characterized by silence and shame. Gay carried her secret alone, unable to tell her parents what had happened. She believed, as many victims do, that she was somehow at fault. At school, the boys spread their version of the story, turning her name into a slur. She learned early that "he said/she said" narratives almost always favor the "he said," and so she swallowed her truth, which "turned rancid" and "spread through the body like an infection." Her internal landscape transformed dramatically. Where once there had been a happy, confident child, there was now a withdrawn, silent girl carrying an unspeakable burden. She writes, "I was broken, shattered and silent. I was numb. I was terrified." The psychological impact manifested in a complete disconnect from her former self. She could no longer feel free or happy or safe. When her family moved to a new state shortly after, she was relieved to escape the immediate environment of her trauma, but the internal damage had already been done. In high school, Gay found small respites from her pain. She immersed herself in theater tech work, finding that backstage, her size didn't matter; only her competence did. One teacher, Mr. McGuinn, recognized something in her dark, violent stories about young girls being tormented. He told her she was a writer and encouraged her to write every day—advice she still follows. Perhaps most importantly, he walked her to the campus counseling center, recognizing that she needed help even if she wasn't ready to fully accept it. The trauma created a profound schism between Gay and her family, despite their love for her. She writes poignantly of how she tried to maintain the facade of the "good girl" they thought her to be, knowing she could never tell them what had happened or what she had become in her own eyes. "There was no room in my life for the truth," she writes, though she now understands that her parents would have supported and helped her. This distance—this inability to be fully known by those who loved her most—became yet another loss stemming from that terrible day in the woods.

Chapter 3: Creating a Fortress: Food as Protection

In the aftermath of trauma, Roxane Gay turned to food not merely for comfort but as a deliberate strategy of self-protection. "I began eating to change my body," she writes. "I was willful in this. Some boys had destroyed me, and I barely survived it. I knew I wouldn't be able to endure another such violation, and so I ate because I thought that if my body became repulsive, I could keep men away." This profound insight reveals how her relationship with food became inextricably linked to her need for safety—her expanding body becoming the fortress within which she could hide. When Gay went to boarding school at Exeter at age 13, she found herself suddenly free from parental supervision and with unlimited access to food. The dining hall was "an all-you-can-eat extravaganza," and she took full advantage, describing how she "reveled in eating whatever I wanted, whenever I wanted." There were burgers and fries at The Grill, submarine sandwiches downtown, pizza delivered to her dorm—all consumed without limits or oversight. Food offered the "only true pleasure" she knew in high school. The weight gain was dramatic. When she returned home for her first Thanksgiving break, her parents were shocked by her transformation—she had gained at least thirty pounds in just two and a half months. Their reaction marked the beginning of what would become a lifelong pattern: her family's alarm and intervention, and her resistance. They took her to doctors, put her on medically supervised diets, and sent her to weight-loss camp, all to little lasting effect. She would lose weight under supervision, then gain it back immediately upon returning to school, deliberately undoing any progress made. Her description of this cycle reveals the complex psychology behind her actions. When she lost weight and received positive attention for her "new body," she felt both the power of social currency that comes with thinness and a terrifying vulnerability. "I was losing my newfound invisibility, and it terrified me," she writes. The smaller body felt unsafe, exposed, and she would quickly retreat to the protection of weight gain. Food became both refuge and rebellion—a way to control at least one aspect of her life when she felt powerless in so many others. By the end of high school, Gay had gained approximately 120 pounds over four years. The pattern continued through college and beyond, with her weight increasing steadily as she built what she calls "a distinct boundary between myself and anyone who dared to approach me." Her relationship with food was not about indiscipline or lack of willpower, as the world might assume, but about survival. "This is what I did," she writes with unflinching honesty. "This is the body I made. I am corpulent—rolls of brown flesh, arms and thighs and belly... The fat created a new body, one that shamed me but one that made me feel safe, and more than anything, I desperately needed to feel safe."

Chapter 4: Living in an Unruly Body: Public Spaces and Private Pain

Living in a fat body, as Gay describes it, means constantly negotiating a world not designed for your existence. "My body is a cage," she writes, describing the physical limitations and pain that accompany her size. Simple activities become complicated ordeals—walking leaves her out of breath, stairs challenge her endurance, and sitting can be an exercise in both discomfort and humiliation. She details the bruises that form on her thighs from chairs with arms, the anxiety that floods her when entering a room where she might be expected to sit, and the constant calculations she must make about space and accessibility. Public spaces present particular difficulties. Airplanes become sites of extreme anxiety and potential humiliation, from the logistics of seat belt extenders to the visible relief of passengers who realize they won't be seated next to her. Restaurants require advance research to determine what kind of seating they offer. Movie theaters and playhouses often have seats too small to accommodate her comfortably. The cumulative effect is a shrinking of her world: "The bigger you are, the smaller your world becomes," she observes with painful clarity. Beyond the physical challenges lies the emotional toll of living in a body that society deems problematic. Gay describes being hyperconscious of how she takes up space, trying to "fold into myself" to minimize her presence. She walks at the edge of sidewalks, hugs walls in buildings, and tucks herself against airplane windows—all attempts to make herself smaller, less intrusive, less offensive to others. This hyperawareness extends to a relentless self-critique: "I am the fattest person in this apartment building. I am the fattest person in this class... I am the fattest person in this restaurant." This refrain becomes a constant, destructive companion. The cruelty of strangers adds another dimension to this experience. Gay recounts being shoved in public spaces, as if her fat "inures me from pain and/or as if I deserve pain, punishment for being fat." Men shout vulgar comments from car windows. Helpful strangers offer unsolicited encouragement at the gym ("Good for you!"), revealing their assumptions about her body and intentions. Even medical professionals fail her, often unable to see past her weight to treat whatever condition actually brings her to their offices. She describes a doctor who listed "morbid obesity" as her primary diagnosis when she came in with strep throat. The emotional and physical pain of living in her body becomes a daily reality that most people in "normal" bodies cannot comprehend. "I am always uncomfortable or in pain," she writes. "I don't remember what it is like to feel good in my body, to feel anything resembling comfort." Yet despite this constant discomfort and the world's hostility, Gay continues to move through it, teaching, writing, speaking—claiming her right to exist in public even as that existence is made unnecessarily difficult by both physical infrastructure and social attitudes.

Chapter 5: Finding Voice: Writing and Self-Expression

Throughout Gay's life, writing has been both sanctuary and salvation. "I often say that reading and writing saved my life," she writes. "I mean that quite literally." As a young girl, she found escape in books, disappearing into worlds where her body and its troubles could not follow her. On the school bus, when classmates teased her and threw her books around, she persisted in reading, finding in literature the solace that eluded her in real life. After her assault, writing became the outlet through which she could express what remained unspeakable. At Exeter, she wrote "dark and violent stories about young girls being tormented by terrible boys and men." Though she couldn't tell anyone what had happened to her, she "wrote the same story a thousand different ways." This creative expression became a lifeline, a way to process her trauma when direct confrontation was impossible. Her English teacher, Mr. McGuinn, recognized her talent and told her she was a writer, encouraging her to write every day—advice she still follows decades later. In college and during her lost years in her twenties, Gay continued to write, even as her life spiraled in various directions. She worked odd jobs, moved frequently, engaged in self-destructive behaviors, but throughout it all, the constancy of writing remained. When she eventually returned to academia, pursuing graduate studies in creative writing at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, writing became her professional focus as well as her personal outlet. She describes working as an editorial assistant for Prairie Schooner, the program's literary magazine, where she learned about the writing world by reading submissions from other aspiring authors. As her career developed, Gay's voice grew stronger and more confident. She began blogging and publishing in online venues, finding communities of readers who connected with her work. Writing offered a way to be seen and valued for her intellect rather than judged for her body: "Through writing, I was, finally, able to gain respect for the content of my character." She found particular freedom in the anonymity writing initially provided—her words could stand independent of her physical appearance. The trajectory of Gay's writing career demonstrates a gradually expanding confidence in her voice. From the private refuge of her journal to academic writing to published essays and fiction, she developed a distinctive style characterized by honesty and intellectual clarity. Her work began to attract attention, leading to speaking engagements, book deals, and a national profile. With this increased visibility came both opportunities and challenges—her body was once again on display, but now it was accompanied by her powerful voice. Writing ultimately provided Gay with the means to reclaim her narrative. Though trauma had silenced her for years, through writing she found a way to tell her truth on her own terms. "I am using my voice," she writes, "not just for myself but for people whose lives demand being seen and heard." This transformation—from silent victim to influential voice—represents perhaps the most profound victory in her ongoing journey toward healing.

Chapter 6: Healing and Acceptance: The Path Forward

The journey toward healing, as Gay describes it, is neither linear nor complete. "I am as healed as I am ever going to be," she writes with characteristic frankness. "I have accepted that I will never be the girl I could have been if, if, if." This acceptance of permanent change—that the trauma she experienced fundamentally altered her life's trajectory—represents an important aspect of her healing process. Rather than pursuing an impossible return to who she might have been, she acknowledges the reality of who she has become. For Gay, healing does not mean forgetting or forgiving those who harmed her. "I will never forgive the boys who raped me and I am a thousand percent comfortable with that because forgiving them will not free me from anything," she states firmly. Instead, her version of healing involves reclaiming her voice, allowing herself to be vulnerable, building meaningful connections with others, and working toward a more humane relationship with her body. Food and weight remain complicated issues for her. She describes oscillating between wanting to lose weight for health reasons and rejecting the cultural pressures that equate thinness with worth. "I am trying to undo all the hateful things I tell myself," she writes. "I am trying to find ways to hold my head high when I walk into a room, and to stare right back when people stare at me." This struggle represents not just personal growth but resistance against societal norms that devalue bodies like hers. An important breakthrough came after breaking her ankle in 2014, an experience that forced her to confront her mortality and her relationship with her body in new ways. During her ten-day hospital stay, surrounded by family and friends who showed up for her, Gay realized "If I died, I would leave people behind who would struggle with my loss." This recognition of being loved and valued challenged her long-held beliefs about her worthlessness. "When I broke my ankle, love was no longer an abstraction. It became this real, frustrating, messy, necessary thing, and I had a lot of it in my life." By the memoir's conclusion, Gay has not "solved" the problem of her body or erased her trauma, but she has reached a place of greater self-awareness and purpose. She acknowledges that part of her healing involves tearing down the fortress she built: "I no longer need the body fortress I built. I need to tear down some of the walls, and I need to tear down those walls for me and me alone." This process—which she describes as "undestroying myself"—represents her ongoing commitment to reclaiming her life from trauma's shadow. The path forward involves continuing to use her voice, both for herself and others. Through her writing and public presence, Gay has transformed her pain into power, creating work that resonates with countless readers who have experienced their own versions of trauma and body struggles. "I am trying to be better than I have been," she writes, embracing the complexity of her journey without demanding perfection of herself. Her healing may be incomplete, but in sharing her truth so courageously, she has created space for others to confront their own truths as well.

Summary

Roxane Gay's memoir stands as a profound testament to resilience in the face of both personal trauma and societal cruelty. Through her unflinching examination of living in a body that both protects and imprisons her, she illuminates the complex interplay between physical existence and emotional survival. Her journey reveals that healing does not necessarily mean complete transformation or forgetting, but rather learning to live with one's truth while gradually reclaiming agency and voice. "I am not the same scared girl that I was," she writes. "I have let the right ones in. I have found my voice." From Gay's experiences, we learn the vital importance of compassion—both for ourselves and for others whose bodies may differ from societal norms. Her story challenges us to recognize how physical spaces, cultural attitudes, and casual cruelties create unnecessary suffering for those in non-conforming bodies. It reminds us that behind every body lies a complex human story that deserves dignity and understanding. For anyone struggling with trauma, body image, or the search for self-acceptance, Gay offers not a neat resolution but something more valuable: the permission to embrace one's complicated truth and the encouragement to find one's voice within that truth. As she writes in her concluding words: "Here I am, finally freeing myself to be vulnerable and terribly human. Here I am, reveling in that freedom."

Best Quote

“What does it say about our culture that the desire for weight loss is considered a default feature of womanhood?” ― Roxane Gay, Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights the book's honest account of Roxane Gay's life and her struggles with body image following a traumatic event. It acknowledges the author's courage in revealing her personal story and the exploration of themes like racism, body shaming, and feminism.\nWeaknesses: The reviewer finds the book repetitive and the language dull, suggesting that it lacks new insights into obesity and its politics. The tone is described as understated and strangely unemotional, which made it difficult for the reviewer to feel attached to the narrative.\nOverall Sentiment: Mixed\nKey Takeaway: While the book offers a raw and honest portrayal of Roxane Gay's life and challenges, it falls short in engaging the reader due to its repetitive nature and lack of emotional depth. The narrative touches on important social issues but does not provide new perspectives on obesity.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.