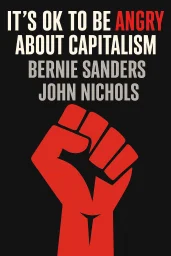

It’s OK to Be Angry About Capitalism

What it Would Take to Change the Status Quo That Enriches Billionaires and Holds the Working Class Down

Categories

Nonfiction, Philosophy, History, Economics, Memoir, Politics, Audiobook, Sociology, Social Justice, Social Issues

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2023

Publisher

Crown

Language

English

ASIN

0593238710

ISBN

0593238710

ISBN13

9780593238714

File Download

PDF | EPUB

It’s OK to Be Angry About Capitalism Plot Summary

Introduction

The current economic system is characterized by extreme inequality, corporate control of political processes, and a pervasive ideology that prioritizes profits over human wellbeing. This stark reality demands not just incremental reforms but a fundamental reconsideration of capitalism itself. The arguments presented challenge the assumption that unfettered capitalism is the only viable economic framework for modern societies. By examining the concentration of wealth in the hands of an increasingly powerful oligarchy, we confront how modern capitalism has moved beyond mere economic organization to become a system that threatens democratic institutions and human dignity. The analysis connects economic arrangements with political power, demonstrating how billionaire influence corrupts democratic processes through campaign finance, media ownership, and regulatory capture. Through rigorous examination of both empirical evidence and theoretical frameworks, readers will discover how economic rights must be understood as human rights, and how transformative change could create a more just, sustainable system that works for everyone, not just the privileged few.

Chapter 1: The Modern Oligarchy: How Billionaires Capture American Democracy

The United States has evolved into an oligarchy where economic power translates directly into political influence. While the country maintains democratic institutions in form, the substance of democracy has been hollowed out by the concentration of wealth in fewer and fewer hands. Today, the three wealthiest Americans possess more wealth than the bottom 50% of the population combined - approximately 165 million people. This extreme inequality isn't merely a matter of differing lifestyles; it represents a fundamental power imbalance that distorts democratic processes. Campaign finance has become the primary mechanism through which billionaires capture political power. Since the 2010 Citizens United Supreme Court decision, which struck down limits on independent political expenditures by corporations and unions, the floodgates have opened for unlimited money in politics. Billionaire contributions to election campaigns increased from $31 million in 2010 to $1.2 billion in 2020, and this figure doubles to $2.6 billion when including billionaires who "self-fund" their own campaigns. This massive influx of money ensures that politicians remain responsive to the interests of their wealthy benefactors rather than their constituents. The influence of the billionaire class extends beyond electoral politics into the governance process itself. Once elected officials take office, they are greeted by thousands of lobbyists whose paychecks are funded by the same billionaires who financed their campaigns. These lobbyists shape legislation, regulations, and policy priorities to benefit their ultra-wealthy patrons. The revolving door between government and industry further cements this relationship, as former officials leverage their connections for lucrative private sector positions, creating a closed loop of influence. The economic structure reinforcing oligarchy has become increasingly centralized. Three investment firms—BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street—now control assets exceeding $20 trillion, equivalent to the entire GDP of the United States. These firms are major shareholders in almost 96% of S&P 500 companies, giving them unprecedented influence over the economy. They are among the largest owners of the major banks, airlines, pharmaceutical companies, and media conglomerates, creating interlocking networks of influence that extend across virtually every sector of the economy. Media concentration has proven particularly damaging to democracy. The same billionaires who dominate politics also control the information landscape through ownership of major media outlets. Six corporations now control approximately 90% of media in the United States, allowing them to shape public discourse, determine which issues receive attention, and influence how those issues are framed. This media control enables billionaires to manipulate public opinion while simultaneously using their wealth to control the political process, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of oligarchic power. Addressing this capture of democracy requires more than simply electing different politicians; it necessitates fundamental structural reforms to the economic system itself. Campaign finance reform, anti-trust enforcement, wealth taxation, and public funding for elections are necessary but insufficient steps. True democratic renewal requires challenging the very foundations of a system that allows billionaires to accumulate such vast fortunes in the first place.

Chapter 2: Economic Rights as Human Rights: Reimagining the Social Contract

The distinction between political rights and economic rights has created a fundamental contradiction in American society. While the Constitution and Bill of Rights guarantee freedom of speech, religion, assembly, and other political liberties, they fail to guarantee the economic foundations necessary for these rights to be meaningfully exercised. This contradiction was recognized by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in his largely overlooked 1944 State of the Union address, where he declared that "true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence." Economic rights encompass the material conditions necessary for human dignity and freedom: the right to healthcare, housing, education, living wages, and retirement security. These rights recognize that meaningful freedom requires more than just the absence of government interference; it requires the positive provision of resources that enable individuals to develop their capabilities and pursue their life goals. When people lack these fundamental economic securities, their political rights become hollow promises, exercised under conditions of desperation and dependency. The deprivation of economic rights manifests in stark statistics that reveal the failure of the current system. Sixty percent of Americans live paycheck to paycheck, unable to weather even minor financial emergencies. Eighty-five million people are uninsured or underinsured, with sixty thousand dying annually because they cannot access needed medical care. The United States has the highest childhood poverty rate among industrialized nations, disproportionately affecting Black and Brown families. The minimum wage has not kept pace with productivity or inflation, leaving millions of full-time workers in poverty. The contrast between the deprivation experienced by ordinary Americans and the extravagant wealth of the billionaire class highlights the moral failure of the current economic arrangement. The richest three billionaires own more wealth than the bottom half of American society—165 million people. CEOs now earn four hundred times what their average employees make. This concentration of wealth represents not just inequality in material resources but also in power, opportunity, and life chances. Establishing economic rights as human rights would transform American society. It would recognize healthcare as a universal entitlement rather than a commodity to be purchased. It would guarantee quality education from early childhood through college without the burden of crushing debt. It would ensure housing security and living wages as basic conditions of citizenship. Most fundamentally, it would reorient the economy toward meeting human needs rather than maximizing profit and shareholder value. The realization of economic rights requires more than legislative action; it demands a shift in societal values and a reimagining of the social contract. It means recognizing that dignity, security, and opportunity should be universal birthright guarantees rather than privileges for the fortunate few. By establishing economic rights as human rights, America would finally fulfill Roosevelt's vision of a society where freedom means not just political liberty but genuine human flourishing for all.

Chapter 3: Healthcare as a Right: The Moral Imperative for Medicare for All

The American healthcare system exemplifies the fundamental contradiction between human needs and profit-driven capitalism. Despite spending approximately $12,530 per capita on healthcare—more than twice what other developed nations spend—the United States leaves 85 million people uninsured or underinsured. This astronomical expenditure, totaling $4 trillion annually or about 20% of GDP, delivers inferior outcomes compared to countries that spend far less. Life expectancy, infant mortality, maternal health, and other key indicators show Americans receiving poorer care despite the enormous sums they pay. The core problem lies in the system's design: American healthcare primarily serves corporate profit rather than patient wellbeing. Insurance companies employ hundreds of thousands of people who have nothing to do with actual healthcare provision. Their sole function is to maximize profits by collecting premiums, denying claims, and creating bureaucratic barriers to care. CEOs of major health insurance companies routinely earn tens of millions in annual compensation while making decisions that deny necessary treatments to patients. In 2021, the six largest health insurance companies made over $60 billion in profits while Americans were dying from preventable conditions. The pharmaceutical industry represents another facet of this profit-centered approach. Americans pay the highest prices in the world for prescription drugs—often ten times what people in other countries pay for identical medications. One in four Americans cannot afford their prescribed medications, forcing many to ration pills or forgo treatment entirely. Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry remains one of the most profitable sectors in the economy, with the CEOs of just eight prescription drug companies making $350 million in total compensation in 2020. Medicare for All would transform this broken system by establishing healthcare as a universal right. Under this single-payer system, every American would receive comprehensive coverage without premiums, deductibles, or co-payments. The program would eliminate the wasteful administrative costs associated with private insurance, negotiate lower drug prices, and remove the financial barriers that currently prevent millions from accessing care. By treating healthcare as a public good rather than a commodity, Medicare for All would align the healthcare system with its proper purpose: healing the sick and promoting wellbeing. The objections to Medicare for All typically center on cost, but research consistently shows that a single-payer system would actually reduce total healthcare spending. The Congressional Budget Office found that Medicare for All would save Americans between $42 billion and $743 billion annually. These savings come from eliminating insurance company profits and administrative waste, negotiating lower drug prices, and preventing expensive emergency care by ensuring timely access to preventive services. The real question is not whether we can afford Medicare for All, but whether we can afford to continue with a system that costs more while delivering less. The moral case for Medicare for All transcends economics. In a society that values human dignity, healthcare cannot be a privilege dependent on employment status or financial resources. The current system, which allows people to suffer and die because they cannot afford care, represents a profound moral failure. Medicare for All would establish the principle that every person deserves care regardless of their economic circumstances, affirming healthcare as a fundamental human right rather than a market transaction.

Chapter 4: Labor's Struggle: Workers Fighting Back Against Corporate Power

Workers in America face a system deliberately designed to undermine their collective power. Despite dramatic increases in productivity over the past fifty years, real wages have stagnated for most Americans. According to the Economic Policy Institute, between 1979 and 2020, worker productivity increased by 61.8% while worker pay increased by just 17%. This growing gap between productivity and compensation represents one of the largest transfers of wealth in American history—from those who create value to those who own capital. Corporate power has systematically dismantled the institutions and policies that once ensured workers received a fair share of economic growth. Union membership has declined from 35% of private-sector workers in the 1950s to less than 6% today. This decline is no accident; it reflects a coordinated campaign by corporate interests to weaken labor organizations through anti-union legislation, aggressive union-busting tactics, and the exploitation of loopholes in labor law. When workers attempt to organize, they face intimidation, mandatory anti-union meetings, threats of facility closure, and illegal retaliation—with employers violating labor laws in 41.5% of union elections. The consequences of diminished worker power extend beyond wages to encompass the entire quality of working life. Americans now work longer hours with less security than workers in comparable countries. The United States remains the only advanced economy without guaranteed paid family leave, paid sick days, or paid vacation time. Workplace injuries have increased as safety regulations are undermined, while the shift to "gig economy" jobs has stripped workers of basic protections and benefits. The pandemic further exposed these vulnerabilities, as millions of "essential workers" were forced to risk their lives without adequate safeguards or compensation. Despite these challenges, a resurgence in labor activism offers hope for rebuilding worker power. Strikes at companies like John Deere, Kellogg's, and Starbucks have demonstrated renewed militancy among workers demanding fair treatment. Union organizing campaigns have emerged in previously unorganized sectors, including tech, media, and service industries. Young workers in particular have embraced unions, with approval ratings for organized labor reaching their highest level since 1965. This new labor movement is connecting workplace issues to broader social concerns, recognizing that economic justice cannot be separated from racial justice, climate justice, and gender equality. International comparisons highlight alternative possibilities for labor relations. In countries like Denmark, Germany, and Sweden, where union density remains high and collective bargaining coverage extensive, workers enjoy higher wages, stronger benefits, greater job security, and more influence over workplace decisions. These countries demonstrate that strong labor movements contribute to broadly shared prosperity rather than hindering economic performance. Their experience shows that the degradation of work in America is not inevitable but rather the product of deliberate policy choices that can be reversed. The revitalization of labor power represents a crucial component of any serious challenge to capitalism. By organizing collectively, workers can counter corporate dominance not just in individual workplaces but in the broader economic and political system. A renewed labor movement has the potential to transform power relations throughout society, ensuring that economic decisions reflect the needs of the many rather than the interests of the few.

Chapter 5: Education for Citizens: Teaching Critical Thinking Over Conformity

Education systems reflect the values and priorities of the societies that create them. In a capitalist system that prioritizes profit maximization and workforce preparation, education inevitably becomes oriented toward creating compliant workers rather than critical thinkers. This approach undermines the democratic potential of education by treating students as future economic inputs rather than as citizens who must develop the capacity to question, analyze, and participate in collective self-governance. The corporate influence on American education manifests in multiple ways. Standardized testing has narrowed curricula to focus on measurable outcomes that satisfy market metrics rather than developing the full range of human capabilities. Schools increasingly adopt business models of management, with principals recast as CEOs and students as customers or products. Corporate partnerships and sponsorships shape educational priorities, while wealthy donors exercise outsize influence through foundation grants that promote market-based reforms like charter schools and voucher programs. Finland offers a contrasting vision of education that prioritizes human development over economic utility. Finnish schools minimize standardized testing, emphasize creative play, maintain small class sizes, and ensure that teachers receive extensive professional training and autonomy. Rather than fostering competition between students, schools, and districts, the Finnish system promotes collaboration and equity. Every school receives adequate resources, and socioeconomic background has less impact on educational outcomes than in almost any other country. Consequently, Finland consistently ranks among the highest-performing education systems in the world while maintaining high levels of student wellbeing and satisfaction. Developing critical thinking requires more than just adding a few courses on logic or reasoning. It demands a fundamental reorientation of educational practice toward questioning rather than conforming, creating rather than consuming, and collaborating rather than competing. Students must learn to identify assumptions, evaluate evidence, recognize logical fallacies, and understand the social and historical contexts that shape knowledge production. They need opportunities to engage with diverse perspectives, tackle complex problems without clear solutions, and develop their own voices through meaningful dialogue with others. Education for citizenship must go beyond abstract principles to include practical experiences of democratic participation. Schools can function as laboratories of democracy where students exercise real decision-making power through school councils, participatory budgeting, community service projects, and collective problem-solving. By practicing democracy rather than just studying it, students develop the skills, habits, and dispositions necessary for active citizenship. They learn that democracy is not simply a system of government but a way of life that requires ongoing engagement and collective responsibility. The struggle for education that promotes critical thinking and democratic citizenship necessarily confronts powerful interests that benefit from a more docile population. Corporate leaders and political elites often prefer citizens who accept rather than question the existing order. Challenging this preference requires reclaiming education as a public good oriented toward human flourishing and democratic empowerment rather than as a private commodity designed to produce human capital for corporate profit. Only then can education fulfill its potential as a transformative force for individual development and social progress.

Chapter 6: Democratic Media: Breaking Corporate Control of Public Discourse

Media concentration has reached crisis levels in the United States, with profound implications for democratic discourse. Approximately 90% of all U.S. media is controlled by just eight major conglomerates—Comcast, Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, Netflix, CBS, Facebook, Fox News, and Hearst. This concentration continues to intensify through mergers and acquisitions, narrowing rather than expanding the range of perspectives available to the public. The illusion of choice masks a reality of homogenized content produced by fewer and fewer decision-makers. Corporate ownership structures create fundamental conflicts of interest that distort public discourse. Media companies dependent on advertising revenue cannot afford to alienate corporate sponsors by critically examining their practices or challenging the economic system that enriches them. Outlets owned by conglomerates with diverse business interests avoid coverage that might harm their parent companies' other ventures. Even more troubling, the same investment firms—BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street—that dominate other sectors of the economy are also major shareholders in media corporations, creating interlocking networks of influence that transcend individual ownership. The consequences of corporate media control extend far beyond bias in particular stories. Corporate media systematically excludes certain topics from discussion altogether—what media scholars call "agenda-setting" and "framing." Issues like class structure, corporate power, and alternatives to capitalism rarely receive sustained attention. International comparisons that might highlight the inadequacies of American healthcare, education, or labor policies are minimized. Complex policy debates are reduced to horse-race coverage focused on political strategy rather than substantive analysis. The result is a narrowing of political imagination that presents the existing system as the only possible reality. Local journalism, essential for democratic accountability at the community level, has been devastated by corporate disinvestment. Since 2005, more than 2,500 local newspapers have closed, creating "news deserts" where citizens have no reliable source of information about local government, schools, or businesses. Those outlets that remain have drastically reduced staff—newspaper employment has dropped 70% since 2005—leaving remaining journalists unable to provide comprehensive coverage. Without robust local reporting, corruption flourishes, civic engagement declines, and community bonds weaken. Creating democratic media requires both policy interventions and grassroots alternatives. Anti-trust enforcement must break up media conglomerates and prevent further consolidation. Public funding for independent, non-profit media—similar to models that have succeeded in countries like Germany and Norway—can provide resources for journalism that serves the public interest rather than corporate profits. Community-owned media cooperatives, worker-owned news organizations, and public media centers can create spaces for voices excluded from commercial outlets. The internet initially promised to democratize media by reducing barriers to entry, but platform monopolies have recreated many of the same problems that plagued traditional media. Facebook, Google, and other tech giants now function as gatekeepers, using opaque algorithms to determine which content reaches audiences. These platforms optimize for engagement rather than information quality, promoting sensationalism and extremism while harvesting user data for targeted advertising. Addressing these challenges requires regulatory frameworks that treat digital platforms as public utilities with public obligations rather than as private businesses with unlimited discretion.

Chapter 7: Building a Political Revolution: A Movement-Based Strategy for Change

Transforming the economic system requires more than electing different politicians or enacting isolated reforms; it demands a comprehensive strategy to build and sustain a mass movement capable of exercising power at multiple levels. This movement must transcend the limitations of electoral politics while still engaging strategically with the political system. It must be rooted in the lived experiences of ordinary people while articulating a compelling vision of structural change. Most crucially, it must shift power relations throughout society rather than simply changing the personnel who administer the existing system. The foundation of this movement-based strategy is organizing at the grassroots level. This means building relationships in workplaces, neighborhoods, schools, and religious communities that develop ordinary people's capacity for collective action. It requires identifying common interests across different constituencies and creating spaces where people can develop political consciousness through shared struggle. Successful organizing connects immediate concerns—whether wages, housing, healthcare, or education—to deeper structural issues, helping participants understand how their personal problems relate to systemic forces. Movement infrastructure provides the organizational backbone for sustained resistance and proactive change. This infrastructure includes labor unions, community organizations, issue-based coalitions, mutual aid networks, alternative media, political education programs, and legal support systems. Unlike traditional political campaigns that mobilize people for elections and then demobilize, movement infrastructure maintains capacity between electoral cycles. It creates independent bases of power that can hold elected officials accountable and continue advancing change regardless of who holds formal office. Electoral engagement remains essential but must be approached differently than conventional politics. Movement candidates should emerge organically from organizing work rather than being selected by party elites or self-appointed based on personal ambition. They should remain accountable to movement organizations rather than to donors or party leadership. Most importantly, electoral campaigns should be viewed as organizing opportunities that build movement capacity regardless of immediate electoral outcomes. Victory means not just winning office but expanding consciousness, developing new leaders, and strengthening movement infrastructure. Ideological clarity distinguishes transformative movements from those that simply seek incremental improvements within the existing system. This requires articulating a coherent analysis of what is wrong with capitalism, why reforms alone cannot solve structural problems, and what alternatives might look like. It means naming enemies—billionaires, corporations, oppressive systems—clearly rather than speaking in generalities about "special interests" or "the establishment." At the same time, this ideological framework must remain flexible enough to incorporate diverse perspectives and adapt to changing conditions. International solidarity connects domestic struggles to global movements challenging capitalism worldwide. The economic system operates globally, with corporations able to move capital across borders while exploiting differences in labor and environmental standards. Effective resistance must be similarly international, sharing strategies, providing mutual support, and coordinating actions across national boundaries. This solidarity builds power by preventing capital from simply relocating to avoid organized opposition while also creating opportunities to learn from successful movements in other countries.

Summary

The challenge to capitalism presented here offers a comprehensive framework for understanding how extreme wealth concentration undermines democracy, human rights, and social welfare. By connecting seemingly disparate issues—from healthcare and education to media ownership and labor rights—into a coherent critique of the economic system itself, this analysis demonstrates how meaningful change requires addressing root causes rather than symptoms. The central insight is that political democracy cannot survive without economic democracy, and that establishing economic rights as human rights represents the unfinished work of creating a truly free society. The path forward demands both intellectual clarity and strategic action. It requires rejecting false choices between incremental reform and revolutionary change, instead building movements that can secure immediate improvements while advancing a long-term vision of transformation. Those seeking to build a more just, sustainable, and democratic future will find in these arguments not just a critique of what exists but a roadmap for creating what might be possible. The ultimate lesson is that challenging capitalism is not merely an economic project but a moral imperative—one that reconnects our economic arrangements with fundamental human values of dignity, freedom, and shared prosperity.

Best Quote

“The very existence of a rapidly expanding billionaire class in the United States is a manifestation of an unjust system that promotes massive income and wealth inequality.” ― Bernie Sanders, It's OK to Be Angry About Capitalism

Review Summary

Strengths: The book's exploration of capitalism's inequities is both provocative and insightful, reflecting Bernie Sanders' direct style. Accessibility is a notable strength, as complex issues are broken down into understandable language. Sanders' ability to articulate widespread frustrations and his use of personal anecdotes make the narrative engaging and relatable. Weaknesses: Some readers perceive a lack of new ideas, with the book reiterating Sanders' established positions without fresh solutions. Occasionally, the narrative veers into polemics, which might alienate those not already aligned with Sanders' views. Overall Sentiment: Reception leans positive, especially among those who share Sanders' political ideology. The book resonates with readers seeking systemic change, though it may not appeal as strongly to those outside his ideological circle. Key Takeaway: The book serves as a rallying cry for transformative change, emphasizing the need for policies like Medicare for All and a living wage to address systemic injustices in the capitalist system.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.