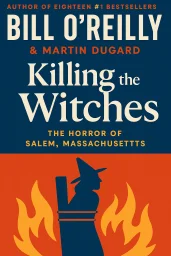

Killing the Witches

The Horror of Salem, Massachusetts

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Religion, Audiobook, True Crime, Book Club, Historical, American History, Witches

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2023

Publisher

St. Martin's Press

Language

English

ISBN13

9781250283320

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Killing the Witches Plot Summary

Introduction

The Oval Office has witnessed some of history's most consequential decisions. From Lincoln's agonizing choice to wage civil war against his fellow Americans to Kennedy's tense standoff during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the American presidency has been shaped by both triumph and tragedy. The weight of leadership has transformed ordinary men into extraordinary figures, while sometimes revealing their deepest flaws. Throughout American history, the presidency has evolved dramatically - from Washington's reluctant acceptance of power to modern presidents commanding global influence through nuclear arsenals and economic might. This evolution reflects America's journey from fragile experiment to superpower. The presidency serves as a mirror reflecting the nation's struggles with democracy, equality, and justice. Whether you're a history enthusiast seeking to understand America's past or simply curious about the personalities who've shaped the nation, these stories of presidential courage, failure, vision and scandal provide invaluable insights into the American experience.

Chapter 1: Founding Visions: Washington to Monroe (1789-1825)

The United States presidency began with a reluctant leader. George Washington, the Revolutionary War hero, had no desire to be king despite some citizens advocating for it. Instead, he embraced the system of checks and balances devised by the Founding Fathers. Washington's presidency established crucial precedents that would shape the office for centuries to come, including the two-term tradition and the careful balance between executive authority and democratic principles. Washington's administration faced immediate challenges. Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, both in his cabinet, represented opposing visions for America's future. Hamilton advocated for a strong central government and national banking system, while Jefferson championed states' rights and agricultural interests. Their philosophical battle would define American politics for generations. When the Whiskey Rebellion erupted in 1794, Washington personally led troops to demonstrate federal authority, establishing that the new government could enforce its laws. John Adams succeeded Washington in 1797, inheriting deteriorating relations with France. The XYZ Affair and subsequent "quasi-war" led Adams to sign the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts, which criminalized criticism of the government. This early test of free speech rights revealed the tension between national security and civil liberties that would repeatedly challenge presidents. Despite his accomplishments in preventing full-scale war with France, Adams lost reelection to his former friend and political rival, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson's presidency dramatically expanded American territory through the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the nation's size despite his own constitutional misgivings about presidential power. This pragmatic decision reflected how the office could evolve beyond strict constitutional interpretation when national interests demanded it. Jefferson also commissioned Lewis and Clark's expedition, opening the continent to westward expansion while setting the stage for future conflicts with Native Americans. James Madison's presidency was defined by the War of 1812, during which British forces burned Washington D.C. and the White House. Despite this humiliation, America emerged with a strengthened sense of national identity. Madison's successor, James Monroe, presided over the "Era of Good Feelings," a period of relative political harmony. His Monroe Doctrine warned European powers against further colonization in the Americas, establishing America's hemispheric leadership and foreshadowing its future global role. By 1825, the presidency had evolved from an experimental office to a powerful institution. These early presidents established enduring traditions while navigating the practical challenges of governance. Their decisions—from Washington's farewell address warning against entangling alliances to Monroe's doctrine of American hemispheric influence—would shape American foreign and domestic policy for centuries to come.

Chapter 2: Expansion and Division: Jackson to Buchanan (1825-1861)

The period from 1825 to 1861 witnessed dramatic territorial expansion alongside growing sectional tensions that would ultimately tear the nation apart. John Quincy Adams, the first son of a president to hold the office, entered the White House under a cloud of controversy after the "corrupt bargain" of 1824. Though intellectually brilliant, Adams struggled to connect with ordinary Americans and accomplish his ambitious agenda for internal improvements. His presidency marked the transition from the aristocratic Founding era to a more populist political landscape. Andrew Jackson's election in 1828 represented this populist shift. "Old Hickory" presented himself as a champion of the common man while simultaneously expanding presidential power. Jackson's forceful personality dominated American politics, from his war against the Second Bank of the United States to his controversial Indian Removal policies. The Trail of Tears, resulting from Jackson's determination to relocate Native American tribes west of the Mississippi, demonstrated how presidential power could be wielded with devastating consequences for vulnerable populations. Territorial expansion accelerated during this era, driven by the concept of Manifest Destiny. James K. Polk, often overlooked despite his significant accomplishments, successfully added vast territories through the Mexican-American War and diplomatic negotiations with Britain over the Oregon Territory. Within four years, Polk achieved all his major objectives, including the acquisition of California, but at the cost of his health—he died just three months after leaving office. This rapid expansion, however, intensified the question that would dominate American politics: would these new territories permit slavery? The presidencies of the 1850s were marked by increasingly ineffective leadership in the face of sectional crisis. Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan each attempted compromises that ultimately failed to resolve the fundamental conflict over slavery's expansion. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, signed by Pierce, effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise and led to bloody confrontations in "Bleeding Kansas." Buchanan's presidency represented the nadir of presidential leadership, as he stood by while southern states began seceding following Abraham Lincoln's election in 1860. This period revealed how presidential character and decision-making could either mitigate or exacerbate national divisions. While some presidents sought compromise, others, like Jackson, imposed their will regardless of consequences. The failure of successive administrations to resolve the slavery question peacefully demonstrated the limits of presidential power when confronting deeply entrenched moral and economic interests. By 1861, the expanding republic stood on the brink of dissolution. The territorial growth that had once symbolized American dynamism and promise had become inextricably linked with the nation's deepest contradiction—a republic founded on liberty that permitted human bondage. The next president would face the ultimate test: preserving the Union itself.

Chapter 3: Civil War and Reconstruction: Lincoln's Legacy (1861-1877)

Abraham Lincoln assumed the presidency in March 1861 as the nation was already unraveling. Seven southern states had seceded before his inauguration, and the attack on Fort Sumter in April forced him to confront the greatest crisis any American president had faced: a full-scale rebellion threatening the nation's existence. Lincoln's extraordinary leadership during this period redefined the presidency itself. He exercised unprecedented executive powers, suspending habeas corpus and issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, justifying these actions as necessary to preserve the Union. Lincoln's vision for the war evolved from simply restoring the Union to a more profound transformation of American society through the abolition of slavery. His Gettysburg Address reframed the nation's founding principles, emphasizing equality rather than just liberty. Despite criticism from both radicals who thought him too cautious and conservatives who thought him too radical, Lincoln maintained a steady course, eventually selecting generals like Grant who shared his determination to achieve total victory regardless of casualties. Lincoln's assassination in April 1865, just days after Lee's surrender at Appomattox, deprived the nation of his leadership during the critical Reconstruction period. His successor, Andrew Johnson, lacked Lincoln's moral clarity and political skills. Johnson, a southern Democrat chosen as Lincoln's running mate to promote national unity, soon revealed himself as sympathetic to former Confederates and hostile to black civil rights. His lenient Reconstruction policies allowed southern states to enact "Black Codes" that effectively reimposed servitude on freed slaves. The ensuing power struggle between Johnson and the Radical Republicans in Congress represented a constitutional crisis over who would control Reconstruction. Johnson's obstruction of Congressional Reconstruction policies led to his impeachment in 1868—the first presidential impeachment in American history. Though he narrowly avoided conviction, Johnson's presidency was effectively neutered, and Congress took control of Reconstruction policy. Ulysses S. Grant, the Civil War hero elected in 1868, attempted to enforce civil rights for freed slaves in the South. His administration vigorously prosecuted the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations. However, Grant's presidency was marred by corruption scandals and economic depression. By his second term, northern public opinion was tiring of Reconstruction, and federal commitment to protecting black rights in the South was waning. The disputed election of 1876 between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden resulted in the Compromise of 1877, which gave Hayes the presidency in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from the South. This effectively ended Reconstruction and abandoned freed slaves to the mercy of resurgent white supremacist regimes. The promise of Lincoln's "new birth of freedom" remained unfulfilled, as southern states systematically disenfranchised black citizens and imposed segregation that would endure for nearly a century.

Chapter 4: Industrial Power and Progressive Reform (1877-1920)

The period from 1877 to 1920 witnessed America's transformation from an agricultural republic into an industrial powerhouse. The presidency during this era evolved from a relatively weak office to a platform for national leadership and reform. Following the Compromise of 1877, Rutherford B. Hayes presided over an America increasingly dominated by industrial titans like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. Hayes himself warned that the concentration of wealth threatened to turn America into a "government of corporations, by corporations, for corporations." The presidencies of the Gilded Age were largely forgettable. James Garfield was assassinated just four months into his term by a deranged office-seeker, highlighting the problematic spoils system. His successor, Chester A. Arthur, surprised many by supporting civil service reform despite his background as a machine politician. Grover Cleveland, the only Democrat to serve as president between 1861 and 1913, championed limited government and sound money policies but struggled to address the economic depression of the 1890s. These presidents generally deferred to Congress on domestic matters and focused narrowly on tariffs, currency, and patronage rather than addressing the social costs of industrialization. The Spanish-American War of 1898 during William McKinley's presidency marked America's emergence as a global power. The acquisition of territories including the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam established the United States as an imperial power with interests beyond North America. This expansion reflected both economic interests and a growing sense of America's "civilizing mission" abroad. McKinley's assassination in 1901 brought Theodore Roosevelt to the presidency, ushering in the Progressive Era. Roosevelt dramatically expanded presidential power and visibility. His "Square Deal" aimed to balance the interests of corporations, workers, and consumers. Roosevelt used the presidency as a "bully pulpit" to advocate for reforms including food and drug regulation, conservation of natural resources, and antitrust enforcement against monopolies. His successor and protégé, William Howard Taft, continued many of Roosevelt's policies but lacked his charisma and political instincts, leading to a split in the Republican Party in 1912. Woodrow Wilson, elected due to this Republican division, further expanded federal authority through his "New Freedom" agenda. The Federal Reserve System, Federal Trade Commission, and progressive income tax all date from this period. Wilson's presidency was ultimately defined by World War I, which he initially kept America out of before leading the nation into the conflict in 1917. His idealistic vision for a postwar order based on self-determination and collective security, embodied in the League of Nations, was ultimately rejected by the Senate and a war-weary American public. The Progressive Era presidents established a model of active executive leadership that would influence their successors throughout the 20th century. By using the presidency as a platform to shape public opinion and drive legislative agendas, Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson transformed the office from its more limited 19th century conception. Their efforts to harness federal power to address the challenges of industrial capitalism—from monopolies to unsafe working conditions—established precedents that would be expanded during future crises, particularly the Great Depression and World War II.

Chapter 5: Depression and War: Roosevelt's Transformation (1920-1945)

The period between 1920 and 1945 transformed America from an emerging world power into the globe's preeminent nation. Following World War I, Americans elected Warren G. Harding, who promised a "return to normalcy" after Wilson's internationalism. Harding's administration was plagued by corruption scandals, most notably Teapot Dome, where his Interior Secretary leased naval oil reserves to private companies in exchange for bribes. Though personally honest, Harding's poor judgment in appointing friends to key positions tarnished his presidency before his sudden death in 1923. Calvin Coolidge, who succeeded Harding, presided over the economic boom of the "Roaring Twenties." His laissez-faire approach to governance—famously summarized in his statement that "the business of America is business"—aligned with the pro-business sentiment of the era. The Coolidge administration saw reduced government spending, tax cuts, and minimal regulation of industry. While the economy initially thrived under these policies, they contributed to speculative excesses that would culminate in the stock market crash of 1929, just months after Herbert Hoover succeeded Coolidge. Hoover, once considered a masterful administrator for his humanitarian work during World War I, found himself overwhelmed by the Great Depression. Though he abandoned traditional Republican orthodoxy by initiating some federal relief efforts, Hoover remained committed to voluntarism and local responsibility rather than direct federal intervention. His inability to address the economic catastrophe effectively led to his landslide defeat by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. Roosevelt's presidency represented a revolutionary expansion of federal power and presidential leadership. His New Deal programs—from banking reforms to Social Security—fundamentally altered the relationship between citizens and their government. FDR's mastery of radio through his "Fireside Chats" established a direct connection with the American people, bypassing traditional media filters. His unprecedented four-term presidency (cut short by his death in 1945) broke Washington's two-term tradition and eventually led to the 22nd Amendment limiting presidents to two terms. As fascism spread across Europe and Japanese militarism threatened Asia, Roosevelt gradually prepared a reluctant America for war. After Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he mobilized the nation for a two-front global conflict. Roosevelt's wartime leadership, in partnership with Churchill and Stalin, shaped the Allied strategy that would ultimately defeat the Axis powers. His vision for the postwar world, including the United Nations, reflected his belief that American security depended on international cooperation. By Roosevelt's death in April 1945, just weeks before victory in Europe, the United States had emerged as the world's dominant economic and military power. The decisions made during this period—from the New Deal's expansion of federal authority to America's full engagement in world affairs—would define the framework of American governance and foreign policy for decades to come. The presidency itself had been transformed from the relatively constrained office of the 19th century into the center of American political life and global leadership.

Chapter 6: Cold War Leadership: Truman to Reagan (1945-1989)

Harry Truman inherited both the conclusion of World War II and the dawning of the atomic age when he succeeded Roosevelt in April 1945. His decision to use nuclear weapons against Japan ended the war but inaugurated an era of existential danger. Truman's presidency established the containment doctrine that would guide American foreign policy throughout the Cold War, from the Marshall Plan rebuilding Western Europe to the formation of NATO and intervention in Korea. Domestically, his Fair Deal sought to extend Roosevelt's reforms, though with limited success against a more conservative Congress. Dwight Eisenhower, the World War II hero elected in 1952, brought a more moderate Republican approach to governance. While maintaining containment abroad, he expanded Social Security, created the interstate highway system, and sent federal troops to enforce school desegregation in Little Rock. Eisenhower warned against the "military-industrial complex" in his farewell address, recognizing how the permanent mobilization required by the Cold War threatened to distort American priorities and values. The 1960s brought dramatic changes through John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Kennedy's New Frontier promised activist government at home and abroad, though his thousand-day presidency was cut short by assassination. His handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis demonstrated how presidential decision-making could literally determine humanity's survival in the nuclear age. Johnson's Great Society represented the high-water mark of liberal governance, with Medicare, Medicaid, civil rights legislation, and voting rights protection transforming American society. However, the escalation of the Vietnam War undermined Johnson's domestic achievements and divided the nation. Richard Nixon's presidency reflected the contradictions of the Cold War era. While pursuing détente with the Soviet Union and opening relations with China, Nixon expanded the Vietnam War before finally negotiating American withdrawal. His domestic policies included environmental protections and wage-price controls that departed from conservative orthodoxy. Ultimately, the Watergate scandal revealed Nixon's abuse of presidential power and led to his resignation in 1974, creating a crisis of confidence in American institutions. The presidencies of Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter struggled with the aftermath of Vietnam and Watergate, along with economic challenges including stagflation. Carter's emphasis on human rights in foreign policy represented an idealistic departure from Cold War realpolitik, though the Iran hostage crisis highlighted the limits of American power. Ronald Reagan's election in 1980 brought a more assertive approach to the Soviet Union, combining military buildup with diplomatic engagement that contributed to the eventual end of the Cold War under George H.W. Bush. Throughout this period, the presidency became increasingly imperial in its powers, particularly in foreign affairs and national security. The tension between presidential authority and democratic accountability, highlighted by Vietnam and Watergate, led to reforms including the War Powers Resolution and strengthened congressional oversight. Yet the existential nature of the Cold War continued to concentrate decision-making power in the White House, establishing precedents that would shape the presidency long after the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991.

Chapter 7: Modern Challenges: America in a Changing World (1989-Present)

The post-Cold War era presented American presidents with a complex new landscape. George H.W. Bush presided over the Soviet Union's collapse and led a broad international coalition in the Gulf War, declaring a "new world order" of international cooperation. However, domestic economic concerns and a third-party challenge from Ross Perot contributed to his defeat by Bill Clinton in 1992. Clinton's "Third Way" centrism reflected the apparent triumph of market democracy, as he balanced the budget while reforming welfare and expanding trade through NAFTA and the WTO. His presidency was marked by strong economic performance but undermined by personal scandal that led to his impeachment, though not conviction. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, dramatically altered the trajectory of George W. Bush's presidency. Initially focused on domestic priorities including tax cuts and education reform, Bush pivoted to a "War on Terror" that included military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq. The latter, justified by intelligence about weapons of mass destruction that proved false, became deeply controversial. Bush's second term saw Hurricane Katrina's devastating impact and the 2008 financial crisis, which required massive government intervention to prevent economic collapse. Barack Obama, the first African American president, took office amid this economic crisis and implemented stimulus measures and financial reforms to address it. His signature achievement, the Affordable Care Act, represented the most significant expansion of healthcare coverage since Medicare. Obama's foreign policy sought to reduce American military commitments while maintaining global leadership through multilateral approaches. His presidency faced intense partisan opposition that limited legislative achievements in his second term and reflected deepening polarization in American politics. Donald Trump's unconventional presidency challenged many democratic norms and traditions. His "America First" approach rejected aspects of the post-World War II international order, questioning alliances, withdrawing from agreements like the Paris Climate Accord, and engaging in trade disputes with allies and competitors alike. Domestically, Trump secured tax cuts and conservative judicial appointments while using executive actions to advance his agenda. His presidency concluded with his unprecedented second impeachment following the January 6, 2021, Capitol riot by his supporters contesting his election defeat. Joe Biden entered office facing multiple crises: the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, economic disruption, racial tensions, and deep political divisions. His administration has sought to restore traditional alliances while confronting rising challenges from China and Russia. Domestically, Biden secured passage of infrastructure investment and climate legislation while navigating the narrowest of congressional majorities. These modern presidencies have operated in an environment transformed by technological change, from the internet to social media, which has revolutionized how presidents communicate with the public and how citizens engage with politics. The 24-hour news cycle and fragmented media landscape have made it increasingly difficult for presidents to set the national agenda or build consensus. Meanwhile, growing polarization has made bipartisan cooperation more elusive, leading presidents to rely more heavily on executive actions that can be reversed by their successors, creating policy instability.

Summary

The American presidency has evolved from Washington's cautious establishment of precedents to today's global leadership position with nuclear command authority. Throughout this transformation, a fundamental tension has persisted between democratic accountability and effective executive power. The most consequential presidents - Lincoln preserving the Union, FDR combating depression and fascism, Reagan navigating the Cold War's end - succeeded by balancing these competing imperatives while articulating a compelling vision that united Americans around shared purpose despite their differences. History suggests that presidential leadership matters most during moments of national crisis, when decisions made in the Oval Office can literally determine the fate of the republic. The presidency's greatest triumphs have come when leaders combined principled vision with pragmatic flexibility, personal humility with institutional boldness, and immediate crisis management with long-term strategic thinking. For citizens today, understanding this complex institution requires recognizing both its extraordinary capacity to advance justice and progress while acknowledging its potential for overreach and abuse when insufficiently constrained by constitutional checks and democratic vigilance. The American presidency remains both the nation's greatest strength and its most significant vulnerability - a reflection of democracy itself.

Best Quote

“The new constitution, although flawed in some areas, is the most liberating government document in the world. For” ― Bill O'Reilly, Killing the Witches: the Horror of Salem, Massachusetts

Review Summary

Strengths: The book's exploration of the social and political climate during the Salem witch trials offers a detailed perspective on the hysteria and fear within Puritan society. Engaging storytelling is a hallmark, blending historical facts into a narrative that appeals to a wide audience. Additionally, it effectively highlights the broader implications of the trials, such as the dangers of mass hysteria and unchecked power.\nWeaknesses: Historical accuracy and depth are points of contention, as some readers feel the book oversimplifies complex events and figures. Occasionally, modern viewpoints are introduced, which can detract from the historical context. Furthermore, more nuanced character development and deeper exploration of personal stories could enhance the narrative.\nOverall Sentiment: The reception is mixed, with appreciation for its engaging and thought-provoking narrative, though it may leave those seeking a comprehensive academic analysis wanting more.\nKey Takeaway: "Killing the Witches" provides insight into a dark chapter of American history by examining the social and political forces behind the Salem witch trials, though it balances accessibility with historical complexity.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.