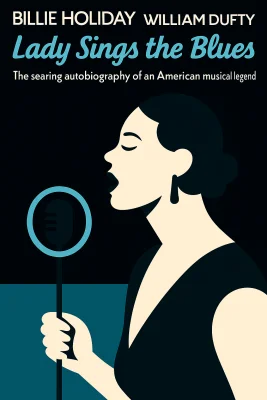

Lady Sings the Blues

The 50th-Anniversay Edition with a Revised Discography

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Memoir, Music, Autobiography, Biography Memoir, African American, Race, Jazz

Content Type

Book

Binding

Paperback

Year

1984

Publisher

Penguin Books

Language

English

ASIN

0140067620

ISBN

0140067620

ISBN13

9780140067620

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Lady Sings the Blues Plot Summary

Introduction

In the dark corners of Baltimore to the bright lights of New York City's jazz clubs, Billie Holiday's voice echoed with a haunting authenticity that transcended mere entertainment. Born Eleanora Fagan in 1915, Holiday emerged from the depths of poverty and trauma to become one of the most influential jazz vocalists of the 20th century. Her unique phrasing, emotional depth, and ability to transform any song into a personal statement revolutionized vocal jazz and popular music. Known as "Lady Day," Holiday possessed a voice that carried the weight of her experiences—the raw pain, resilient spirit, and unflinching honesty that defined both her art and her tumultuous life. Holiday's journey reflects America's complex social landscape during the mid-20th century. Her struggles with racial discrimination, substance abuse, and legal persecution mirrored the harsh realities faced by many African Americans during this era. Yet through it all, she maintained an artistic integrity that remains unparalleled. From her groundbreaking civil rights protest song "Strange Fruit" to her deeply personal interpretations of standards like "God Bless the Child," Holiday's legacy extends far beyond music. Her story is one of extraordinary talent meeting extraordinary adversity—a testament to the transformative power of art and the indomitable human spirit in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles.

Chapter 1: Troubled Beginnings: Baltimore to Harlem (1915-1933)

Billie Holiday's early life was marked by instability and hardship. Born Eleanora Fagan in Philadelphia in 1915, she was raised in Baltimore by her mother Sadie, as her father Clarence Holiday was largely absent pursuing his career as a jazz guitarist. The family struggled financially, with young Eleanora often left in the care of relatives while her mother worked as a maid. "Mom and Pop were just a couple of kids when they got married," Holiday would later reflect. "He was eighteen, she was sixteen, and I was three." This unconventional family dynamic set the stage for a childhood marked by constant upheaval. At just ten years old, Holiday experienced a traumatic event that would haunt her for life. She was sexually assaulted by a neighbor, and in a cruel twist of fate, she was sent to a Catholic institution for "wayward girls" rather than receiving support as a victim. This injustice represented her first bitter taste of a judicial system that would later become a recurring antagonist in her life. During her confinement, Holiday was subjected to harsh discipline, including being locked in a room with a deceased resident as punishment—an experience that left deep psychological wounds. Education became secondary to survival for young Eleanora. By age twelve, she had dropped out of school after completing only the fifth grade. She began working alongside her mother, scrubbing marble steps and cleaning houses for white families in Baltimore. The backbreaking labor paid mere pennies, but it was during this time that Holiday found solace in music. She would listen to recordings of Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith on the victrola at a local brothel, where she ran errands in exchange for the privilege of hearing these transformative sounds. At fourteen, Holiday followed her mother to Harlem, the vibrant cultural center of Black America in the 1920s. The move marked a significant turning point. In this new environment, the streets of Harlem became both classroom and battlefield for the teenager. She worked briefly as a prostitute in a brothel, an experience she never tried to hide in later years. It was during this period that she adopted the name "Billie," inspired by her favorite movie actress, Billie Dove, creating a new identity for herself as she navigated the harsh realities of urban life during the Great Depression. By 1930, at just fifteen years old, Holiday had begun singing in Harlem's nightclubs. Her first performances at places like Pod's and Jerry's revealed a raw, untrained talent that immediately captivated audiences. As she would later recall, "When I finished, everybody in the joint was crying in their beer, and I picked thirty-eight bucks up off the floor." The transformation from Eleanora Fagan to Billie Holiday had begun—a reinvention born of necessity, resilience, and extraordinary talent. These formative experiences in poverty and hardship would later infuse her singing with an emotional authenticity that could not be taught or imitated.

Chapter 2: Rise to Stardom: Defying Racial Barriers in Jazz (1933-1941)

Billie Holiday's ascent in the jazz world began in 1933 when producer John Hammond discovered her performing in a small Harlem club. Struck by her distinctive vocal style, Hammond arranged for the eighteen-year-old Holiday to record with Benny Goodman, then an up-and-coming clarinetist. Her first recording session produced "Your Mother's Son-in-Law" and "Riffin' the Scotch," earning her just thirty-five dollars but marking the beginning of a revolutionary recording career. With no formal music training and unable to read sheet music, Holiday relied on her innate musicality and emotional intelligence. "I don't think I ever had a better recording session," Hammond would later remark, recognizing the raw talent he had discovered. Throughout the mid-1930s, Holiday recorded a series of masterpieces with pianist Teddy Wilson's orchestra, featuring jazz luminaries like Lester Young, whose saxophone complemented Holiday's voice with remarkable sympathy. Young gave her the nickname "Lady Day," while she called him "Prez"—a term of endearment reflecting their deep musical connection. Their collaborations on songs like "This Year's Kisses" and "I Must Have That Man" showcased Holiday's innovative approach to timing and phrasing. Rather than following traditional rhythmic patterns, she manipulated tempo and emphasis, transforming popular songs into personal expressions of joy or heartbreak. In 1938, Holiday joined Artie Shaw's orchestra as the first Black female vocalist to tour with a white band—a groundbreaking yet painful experience. Traveling through the segregated South, she faced constant humiliation: forced to use freight elevators, barred from dining rooms, and sometimes prevented from appearing on stage with the band. After one particularly degrading incident when a hotel refused to let her enter through the front door, Holiday quit. "I don't want to sing for people who would treat me or any other colored person like that," she declared, demonstrating the dignity and self-respect that would characterize her response to racism throughout her career. Holiday's 1939 recording of "Strange Fruit," a haunting protest against lynching, marked a turning point in her career and in American music history. When her record label Columbia refused to record such controversial material, she turned to the independent Commodore Records. The song required tremendous courage to perform—Holiday often closed her sets with it, leaving the stage immediately after in tears. Despite radio stations banning the recording and many venues prohibiting its performance, "Strange Fruit" became Holiday's first major hit, selling over a million copies and establishing her as an artist willing to use her platform for social commentary. By 1941, Holiday had achieved remarkable success on her own terms. Her residency at Café Society, New York's first integrated nightclub, attracted diverse audiences and critical acclaim. Yet commercial success remained elusive compared to contemporaries like Ella Fitzgerald. The music industry, reflecting broader societal prejudices, often marketed Holiday as "exotic" rather than recognizing her artistic innovations. Nevertheless, she had fundamentally changed vocal jazz by demonstrating that a singer could be as creative and improvisational as any instrumentalist. As fellow vocalist Carmen McRae would later observe: "There's a whole generation of singers who wouldn't exist if not for Billie Holiday. She showed us all that a song could be your own story."

Chapter 3: Fighting Addiction: The Personal Battles Behind the Music

Billie Holiday's battle with addiction began in the early 1940s, at the peak of her artistic powers. The demanding schedule of performing, constant racial discrimination, and the emotional toll of channeling her pain into her music created a perfect storm that led her to seek escape. "I had the white gowns and the white shoes. And every night they'd bring me the white gardenias and the white junk," Holiday later recalled, referring to the heroin that became both solace and prison. Her initial drug use reflected a common pattern among performers of the era—substances offered temporary relief from exhaustion and emotional strain, but quickly evolved into dependency. What set Holiday's struggle apart was how mercilessly her addiction was exploited by the legal system. In 1947, she was arrested for narcotics possession and sentenced to a year in a federal rehabilitation facility in West Virginia. Unlike white celebrities with similar problems who received treatment or sympathy, Holiday faced the full force of punitive drug laws. Her arrest was part of Federal Bureau of Narcotics commissioner Harry Anslinger's targeted campaign against Black jazz musicians. As she described the experience: "It was called 'The United States of America versus Billie Holiday.' And that's just the way it felt." Upon her release, Holiday found herself in an impossible situation. Her felony conviction meant she lost her New York City cabaret card—a permit required to perform in venues serving alcohol. This effectively banned her from most jazz clubs and prevented her from earning a living in the city that had been her musical home. Remarkably, just ten days after her release from prison, she performed a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall, demonstrating her enduring appeal. The audience's rapturous response proved that while the legal system had condemned her, the public had not. The 1950s brought continued persecution. Federal agents, acting on tips from informants in Holiday's inner circle, repeatedly targeted her for drug arrests. In 1956, while hospitalized for heart and liver problems caused by years of substance abuse, she was arrested in her hospital bed and handcuffed to a gurney—a particularly cruel episode that revealed the extent of authorities' determination to make an example of her. Despite these indignities, Holiday continued to perform whenever possible, her voice now transformed by hardship into an even more expressive instrument. Throughout her struggle with addiction, Holiday maintained remarkable artistic integrity. Unlike many performers whose work suffered due to substance abuse, she continued to evolve as an artist. Her later recordings, particularly the 1958 album "Lady in Satin," revealed new depths of emotional expression. As jazz critic Leonard Feather noted, "The voice is wedded to the meaning of each song in a way that happens rarely in any kind of music." Her battle with addiction, while devastating to her health and legal standing, paradoxically contributed to her artistic authenticity. Each performance became a testament to survival, with Holiday transforming her personal pain into universal expressions of human resilience.

Chapter 4: Strange Fruit: Confronting America's Racial Divide

"Southern trees bear a strange fruit, blood on the leaves and blood at the root..." When Billie Holiday first performed these haunting lines at Café Society in 1939, she transformed American popular music. "Strange Fruit," a poem about lynching written by Jewish schoolteacher Abel Meeropol under the pseudonym Lewis Allen, became Holiday's signature protest against racial violence. The song represented an unprecedented merging of political statement with popular entertainment. When Holiday finished singing it at Café Society, the room would go completely dark, with only her face illuminated by a spotlight. Then silence—no encore, no bows. "I walked off the stage and into the dressing room," she later recalled, "and I was sick to my stomach every time." Holiday's decision to record and regularly perform "Strange Fruit" came at significant personal risk. Radio stations refused to play it, many venues prohibited its performance, and she faced threats from those who wanted to silence her message. The FBI began keeping a file on Holiday, viewing her performance of the song as potentially subversive. Despite these pressures, she insisted on performing it throughout her career, understanding its power and necessity. "It reminds me of how Pop died," she said, referring to her father Clarence Holiday, who was denied medical treatment for pneumonia at southern hospitals because of his race and died as a result. The song's impact extended far beyond the music world. Many historians credit "Strange Fruit" with helping catalyze the civil rights movement by bringing the horror of lynching into America's cultural consciousness. At a time when mainstream media largely ignored racial violence, Holiday forced audiences to confront this reality. White listeners who came for entertainment instead received an education. As author Angela Davis noted, "When Billie sang 'Strange Fruit,' she was establishing a tradition of musical resistance to racism that would influence generations of artists." Holiday's approach to performing "Strange Fruit" demonstrated her remarkable artistic instincts. Rather than delivering it as an overtly angry protest, she sang with restrained emotion that made its impact even more devastating. Her slow, deliberate phrasing gave each word weight, forcing listeners to confront the imagery. As critic John Bush wrote: "Holiday's voice was the sound of vulnerability and strength simultaneously—the perfect instrument for conveying both the horror of the song's subject and the dignity of its response." This artistic choice reflected Holiday's understanding that understatement could be more powerful than shouting. The legacy of "Strange Fruit" illustrates how Holiday transcended being merely an entertainer to become a cultural force. In an era when Black performers were often expected to be apolitical and pleasing to white audiences, Holiday refused this compromise. The courage this required cannot be overstated. Each performance of "Strange Fruit" was an act of resistance, and through it, Holiday established that popular music could address the most painful aspects of American society. As author Farah Jasmine Griffin observed, "In singing 'Strange Fruit,' Holiday wasn't just performing a song—she was performing an act of citizenship and moral witness when official channels for such testimony were closed to Black Americans."

Chapter 5: Musical Legacy: Creating a Unique Vocal Style

Billie Holiday revolutionized vocal jazz through her innovative approach to timing and phrasing. Unlike her contemporaries who often adhered closely to written melodies, Holiday treated songs as flexible frameworks for personal expression. She played with rhythm much like a horn player, sometimes lagging behind the beat, sometimes rushing ahead, creating tension that resolved in unexpected moments. As she explained, "I don't think I ever sing the same way twice. The blues is a feeling, and I can't put any rules to it." This approach transformed standards like "Embraceable You" and "The Man I Love" into vehicles for profound emotional communication rather than mere entertainment. Holiday's distinctive voice, with its limited range and slightly raspy quality, turned what might have been considered technical limitations into artistic strengths. She used her voice like an instrument, emphasizing certain words, stretching syllables, and employing subtle shifts in tone to convey meaning. Lester Young, her frequent collaborator, once remarked, "Lady sings the way I play. We're telling the same story, just with different tools." Indeed, Holiday's approach was fundamentally instrumental—she absorbed the techniques of jazz saxophonists and trumpeters, applying them to vocal performance in ways that had never been attempted before. The emotional authenticity in Holiday's performances set a new standard for interpretive singing. She insisted on making each song personally meaningful, infusing even the most conventional lyrics with lived experience. "If I'm going to sing like someone else, then I don't need to sing at all," she famously stated. This commitment to authenticity influenced generations of singers across genres, from Frank Sinatra (who openly acknowledged his debt to Holiday) to Janis Joplin and Nina Simone. As Tony Bennett observed, "Billie Holiday taught all of us that the most important thing is to be yourself, no matter what that means." Holiday's compositions, though relatively few, revealed her gifts as a songwriter. "God Bless the Child," co-written with Arthur Herzog Jr. after an argument with her mother over money, became one of her most enduring works. The song's philosophical lyrics reflecting on self-reliance ("Mama may have, Papa may have, but God bless the child that's got his own") demonstrated her ability to transform personal experience into universal wisdom. Similarly, "Don't Explain," written after discovering a husband's infidelity, captured the complex emotions of betrayal and resigned acceptance in deceptively simple language. By the time of her death in 1959, Holiday had fundamentally altered expectations of what vocal jazz could be. Her approach—treating the voice as an instrument, using songs as vehicles for personal expression, and prioritizing emotional truth over technical display—became the foundation upon which modern jazz singing was built. As critic Gary Giddins wrote, "Before Holiday, American popular singing was about beauty, sentiment, and technique. After her, it was about truth." This shift represented not just an artistic evolution but a democratization of music—Holiday proved that authentic expression could transcend technical virtuosity, opening paths for diverse voices in American music.

Chapter 6: Later Years: European Success and American Struggles

Billie Holiday's final years presented a stark contrast between her reception in Europe and America. In 1954, with her New York City cabaret card still revoked due to her narcotics conviction, Holiday embarked on her first European tour. The welcome she received astounded her. In countries like France, Sweden, and England, she was treated as a serious artist rather than a criminal. "Don't tell me about those pioneer chicks hitting the trail with the hills full of redskins," Holiday later remarked about her European travels. "I'm the girl who went through Europe with sixteen white cats and the hills were full of respect." European audiences appreciated her artistry without the racial and legal baggage that had come to define her American career. Upon returning to America, Holiday faced continuing persecution. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics, under Harry Anslinger's direction, maintained its campaign against her. In February 1956, she was arrested again on narcotics charges in Philadelphia—a case many believed was manufactured by authorities determined to make an example of her. Despite deteriorating health, Holiday demonstrated remarkable resilience, continuing to perform whenever possible. Her 1956 autobiography "Lady Sings the Blues," though containing factual inaccuracies, provided a powerful account of her struggles with racism, addiction, and legal harassment. Holiday's voice underwent significant changes in these final years. The clear, vibrant instrument of her youth had been transformed by hard living and illness into a more fragile, weathered sound. Yet many critics and fellow musicians considered this later voice even more expressive. As Jimmy Rowles, her pianist in the late 1950s, observed: "She had lost range and flexibility, but she had gained something else—she could break your heart with a single note." This evolution was documented on her penultimate album, "Lady in Satin" (1958), where her vulnerable vocals, backed by lush strings, created an atmosphere of profound emotional intimacy. The final chapter of Holiday's life was marked by declining health. Years of substance abuse had taken their toll, leaving her with cirrhosis of the liver and heart problems. In May 1959, she was hospitalized for liver and heart disease. Even in this condition, she was not free from harassment—police officers were stationed in her hospital room, and she was arrested for drug possession while bedridden. This final indignity symbolized the relentless persecution she had faced throughout her career. On July 17, 1959, Billie Holiday died at age 44, with just $0.70 in her bank account and $750 strapped to her leg—a final, heartbreaking commentary on her financial exploitation. Despite these struggles, Holiday's final performances revealed an artist still capable of profound communication. A 1957 television appearance on "The Sound of Jazz," featuring a reunion with Lester Young, produced one of the most moving moments in jazz history. Their performance of "Fine and Mellow" captured the essence of their musical relationship, with Young's tender saxophone solo bringing tears to Holiday's eyes. This moment encapsulated what made Holiday extraordinary—even at the end, physically diminished and socially marginalized, she could still access and communicate emotional truths that transcended her circumstances, creating art that would resonate for generations to come.

Chapter 7: Love and Relationships: Finding Strength Through Hardship

Billie Holiday's romantic life was marked by a series of tumultuous relationships that both sustained and damaged her. From an early age, she sought stability and protection in her connections with men, yet repeatedly found herself involved with partners who exploited her financially, physically abused her, or enabled her drug addiction. Her first marriage to Jimmy Monroe in 1941 began promisingly but quickly deteriorated. "I'm not the first—or last—chick who got married to try to prove something to somebody," Holiday later reflected. When she discovered Monroe's infidelity, her pain inspired the haunting composition "Don't Explain," with its resigned opening line: "Hush now, don't explain, just say you'll remain." Holiday's relationships with men often mirrored the power dynamics she experienced in the music industry and society at large. Her second husband, trombonist Jimmy Monroe, and later her manager John Levy, both physically abused her while controlling her finances. These relationships created a destructive pattern where Holiday's dependency—emotional, financial, and eventually chemical—trapped her in cycles of exploitation. Yet she demonstrated remarkable resilience, consistently finding the strength to leave these situations despite the personal and professional costs. Not all of Holiday's significant relationships were romantic. Her connection with saxophonist Lester Young represented one of the most important musical partnerships in jazz history. Their musical chemistry was extraordinary—Young's light, floating saxophone perfectly complemented Holiday's vocal approach. They developed their own language of affection and understanding, with Young giving her the nickname "Lady Day" while she called him "Prez." When Young died in March 1959, just months before Holiday's own death, she was devastated. Their final reunion on the 1957 television special "The Sound of Jazz" remains one of the most poignant moments in music history. Holiday's relationship with her mother Sadie, whom she affectionately called "The Duchess," was complex and sometimes contentious, yet remained central to her emotional life. Despite their conflicts, Holiday financially supported her mother throughout her career, eventually helping Sadie open a restaurant called "Mom Holiday's." When Sadie died in 1945, Holiday was devastated. The loss inspired one of her most personal compositions, "God Bless the Child," which originated from an argument with her mother over money. The song's message of self-reliance ("God bless the child that's got his own") reflected Holiday's hard-earned wisdom about independence. In her final years, Holiday found a measure of stability with Louis McKay, whom she married in 1957. Though their relationship was not without problems, McKay demonstrated genuine concern for Holiday's wellbeing, attempting to help her overcome her addiction and standing by her during her final hospitalizations. "Louis was with me," she said of her final arrest. "They carried us off together and Louis held my hand and whispered: 'Lady, don't you worry about a thing. You and I are going to beat this thing.'" This loyalty provided Holiday with rare emotional support during her final struggles, suggesting that despite the many destructive relationships in her life, she never abandoned the hope of finding genuine connection and understanding.

Summary

Billie Holiday's life journey from the streets of Baltimore to the pantheon of musical greats embodies a triumph of artistry over adversity. She transformed the pain of discrimination, addiction, and persecution into timeless musical expressions that continue to resonate with listeners decades after her death. Her legacy extends far beyond her innovations in vocal technique or her catalog of recordings—Holiday showed that authentic artistic expression could transcend social barriers and speak universal truths. In doing so, she redefined not just jazz singing, but the very purpose of popular music, proving it could be a vehicle for profound emotional and social commentary. The most powerful lesson from Holiday's life may be the relationship between suffering and creation. Rather than allowing her hardships to silence her, Holiday channeled them into her art, creating beauty from pain without romanticizing her struggles. As she once observed, "You've got to have something to eat and a little love in your life before you can hold still for any damn body's sermon on how to behave." This hard-earned wisdom reminds us that compassion must precede judgment, and that the most meaningful art often emerges from the deepest human experiences. For anyone seeking to understand the transformative power of music, the complexity of American race relations, or the resilience of the human spirit, Holiday's story offers invaluable insights that remain as relevant today as when she first raised her voice against injustice and heartbreak.

Best Quote

“Everyones got to be different. You can't copy anybody and end up with anything. If you copy, it means you're working without any real feeling. And without feeling, whatever you do amounts to nothing.” ― Billie Holiday, Lady Sings the Blues

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights the unique and emotive quality of Billie Holiday's voice, describing it as a blend of raw pain and sass. It also emphasizes her ability to convey deep emotions through her music, supported by her personal experiences and immaculate phrasing. Weaknesses: Not explicitly mentioned. Overall Sentiment: Enthusiastic Key Takeaway: The review conveys a deep appreciation for Billie Holiday's music, emphasizing her distinctive voice and emotional depth. It reflects on the personal impact of her music on the reviewer, who associates it with significant memories and experiences, underscoring Holiday's enduring influence in the jazz and blues genres.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.