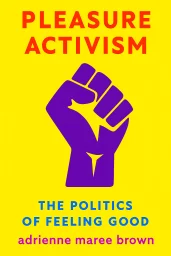

Pleasure Activism

The Politics of Feeling Good

Categories

Nonfiction, Self Help, Politics, Feminism, Sexuality, Essays, Social Justice, Activism, LGBT, Queer

Content Type

Book

Binding

Paperback

Year

2019

Publisher

AK Press

Language

English

ISBN13

9781849353267

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Pleasure Activism Plot Summary

Introduction

The radical proposition that pleasure is not merely personal but deeply political challenges conventional approaches to social justice work. By positioning joy and sensual fulfillment as essential components of liberation rather than frivolous distractions, this framework invites us to reconsider how sustainable social change actually happens. Traditional activism often valorizes sacrifice, suffering, and burnout—inadvertently reproducing the very systems of exploitation it seeks to dismantle. What if instead, our movements themselves embodied the joy, connection, and aliveness we hope to create in the world? This perspective draws from Black feminist traditions, particularly Audre Lorde's groundbreaking work on the erotic as power, while expanding into contemporary practices across multiple domains. The revolutionary potential lies in recognizing that pleasure is not a privilege to be enjoyed after liberation is achieved, but a resource and compass for the journey itself. When marginalized communities reclaim their right to joy despite systems designed to deny it, they engage in profound acts of resistance. Through examining how pleasure intersects with trauma healing, sexual liberation, harm reduction, and movement sustainability, we discover that how we pursue justice may be as important as what we're fighting for.

Chapter 1: The Erotic as Power: Audre Lorde's Radical Framework

Audre Lorde's conceptualization of the erotic as power fundamentally reshapes how we understand resistance and liberation. In her groundbreaking essay "Uses of the Erotic," Lorde defines the erotic not merely as sexual desire but as a profound life force that connects us to our deepest feelings, our capacity for joy, and our sense of satisfaction across all domains of life. This erotic knowledge provides an internal measure against which we can evaluate our experiences, helping us recognize when we are settling for less than we deserve. Far from being a distraction from serious political work, this capacity for deep feeling becomes an essential resource for sustainable activism. Systems of oppression deliberately suppress this erotic power, particularly for women and marginalized communities. By relegating the erotic exclusively to the bedroom or distorting it into pornography (which Lorde defines as sensation without feeling), dominant culture attempts to disconnect people from this vital source of knowledge and energy. This suppression serves political purposes—people disconnected from their erotic power are easier to control, exploit, and convince to accept conditions that do not serve their flourishing. When we cannot access what truly brings us joy, we become more susceptible to manipulation and less able to envision alternatives to current systems. The revolutionary potential of reclaiming erotic power lies in its ability to disrupt patterns of self-denial and resignation. When we reconnect with our capacity for deep feeling and satisfaction, we become less willing to accept situations, relationships, or systems that diminish us. As Lorde writes, "In touch with the erotic, I become less willing to accept powerlessness, or those other supplied states of being which are not native to me, such as resignation, despair, self-effacement, depression, self-denial." This refusal to settle for less than joy becomes a powerful form of resistance, particularly for those whose access to pleasure has been systematically denied. This framework challenges the compartmentalization of our lives into separate spheres. The erotic becomes a bridge connecting the spiritual and political, the personal and communal. It infuses all aspects of existence—work, art, friendship, activism—with the possibility of satisfaction and joy. When we bring this erotic consciousness to our justice work, we transform it from obligation into desire, from sacrifice into fulfillment. This integration creates more sustainable movements that nourish rather than deplete participants. Significantly, Lorde emphasizes that erotic knowledge is not individualistic but relational. The sharing of joy and pleasure creates connections between people that can transcend differences and build solidarity. This sharing distinguishes the erotic from exploitation—using another's feelings without consent constitutes abuse, while mutual sharing of pleasure builds power and possibility. When movements create spaces for authentic connection and joy, they prefigure the world they seek to create rather than merely fighting against current conditions.

Chapter 2: Beyond Self-Indulgence: Pleasure as Political Resistance

Reclaiming pleasure as political resistance requires confronting the persistent misconception that pleasure is merely self-indulgent or frivolous. This dismissal serves systems of oppression by disconnecting marginalized communities from a vital source of power and resilience. When certain bodies—particularly those of women, people of color, disabled people, and queer and trans individuals—are systematically denied access to pleasure or punished for seeking it, the pursuit of joy becomes an act of defiance. The right to experience pleasure in a body that has been deemed unworthy of it constitutes a profound challenge to dehumanizing systems. Capitalism commodifies pleasure while simultaneously restricting access to it, creating a paradoxical relationship where pleasure is constantly advertised but rarely fulfilled. We are sold endless products promising satisfaction while being denied the conditions that would allow for genuine joy: adequate rest, meaningful connection, economic security, and freedom from violence. This commodification transforms pleasure from an inherent capacity into a scarce resource, something to be purchased rather than experienced as a birthright. Pleasure activism challenges this commodification by reclaiming joy as something that cannot be fully captured by market logics. For communities facing ongoing trauma from systemic violence and oppression, pleasure becomes essential for survival and healing. When external conditions remain hostile, the ability to access moments of joy, connection, and aliveness provides crucial resources for continuing resistance. This doesn't mean ignoring or bypassing pain but rather ensuring that pain doesn't become the only experience available. The capacity to feel pleasure alongside grief, to experience joy even in difficult circumstances, creates resilience that purely suffering-focused approaches to justice cannot sustain. Pleasure activism distinguishes between numbing activities that provide temporary escape and genuine pleasures that increase capacity and connection. Many coping mechanisms that appear pleasurable—excessive consumption, addictive scrolling, numbing through substances—actually leave us more depleted and disconnected. True pleasure, by contrast, enhances our sense of aliveness and connection, leaving us more rather than less capable of engaging with reality. Developing discernment between these experiences helps us resist the superficial pleasures offered as compensation for deeper exploitation. The politics of pleasure extends to questioning who has access to rest, leisure, and sensual fulfillment. When certain communities face criminalization for the same activities others enjoy without consequence, pleasure becomes a matter of justice. When working conditions deny some people the time and energy for joy while granting others abundant leisure, pleasure becomes a class issue. By demanding universal access to the conditions that make pleasure possible—safety, rest, bodily autonomy, economic security—pleasure activism connects personal experiences to structural transformation.

Chapter 3: Embodied Liberation: Healing Trauma Through Collective Joy

Trauma lives in our bodies, creating patterns of disconnection, hypervigilance, and numbing that persist long after threatening events have passed. For marginalized communities, trauma often results not just from isolated incidents but from ongoing systemic violence and oppression. Conventional approaches to trauma healing frequently focus exclusively on processing pain and developing coping strategies, which, while necessary, can inadvertently reinforce trauma-centered identities. Embodied liberation offers a complementary approach that actively cultivates experiences of joy, connection, and pleasure as essential components of healing. Collective joy provides a powerful antidote to the isolation that trauma creates. When we dance, celebrate, create art, or share pleasure together, we generate experiences that directly contradict the disconnection and powerlessness of trauma. These shared expressions of aliveness help rewire neural pathways shaped by trauma, creating new possibilities for embodiment and connection. Importantly, collective joy doesn't deny or bypass pain but exists alongside it, expanding our capacity to hold the full spectrum of human experience. This integration allows for more complete healing than approaches focused solely on processing trauma. Reclaiming pleasure after trauma often requires specific practices and supportive contexts. Many survivors experience disconnection from bodily sensations, difficulty with boundaries, or shame around desire. Healing may involve somatic practices that gently rebuild awareness of and trust in bodily sensations, consent-centered spaces that honor autonomy, and communities that affirm the right to pleasure regardless of past experiences. Rather than pushing survivors toward particular expressions of sexuality or joy, embodied liberation honors each person's unique healing journey and timeline. Cultural expressions of collective joy have historically served as resistance to oppression. From enslaved people creating music and dance despite brutal conditions to underground queer balls creating spaces of celebration amid persecution, marginalized communities have long recognized joy as essential to survival. These traditions remind us that pleasure isn't a luxury to be pursued after liberation but a vital resource for sustaining resistance and imagining alternatives to oppressive systems. By studying and honoring these traditions, contemporary movements can incorporate their wisdom into current liberation practices. Healing through collective joy also challenges individualistic models of wellness that place responsibility for recovery solely on those who have been harmed. By creating cultures and communities that prioritize pleasure, consent, and care, we address the conditions that allow trauma to occur in the first place. This shifts focus from helping individuals adapt to harmful systems toward transforming those systems to support collective flourishing. When movements create spaces where people can experience safety, connection, and joy together, they provide embodied experiences of the world they're working to create.

Chapter 4: Decolonizing Desire: Unlearning Oppressive Patterns

Decolonizing desire requires a profound unlearning of the ways colonial, patriarchal, and white supremacist systems have shaped our most intimate longings. These systems have not only controlled bodies through external violence but have colonized our imaginations, teaching us to desire in ways that reinforce hierarchies of race, gender, ability, and size. Our attractions, preferences, and fantasies are not formed in a vacuum but are shaped by media representations, cultural narratives, and social rewards that privilege certain bodies and expressions while devaluing others. True liberation demands we examine whose bodies are deemed desirable, what forms of pleasure are legitimized, and how our own desires may have been shaped by oppressive narratives. This examination isn't about policing desire or creating new hierarchies of political correctness. Rather, it involves developing awareness of how our desires have been shaped and making conscious choices about which patterns we wish to reinforce or transform. The goal isn't perfection but intentionality—moving from unconscious reproduction of harmful patterns toward more conscious cultivation of desires that align with our values. This process requires compassion rather than judgment, recognizing that we have all been shaped by systems not of our making while still taking responsibility for our choices within those systems. For marginalized communities, reclaiming desire often involves healing from specific forms of objectification and fetishization. Black and Brown bodies have been hypersexualized according to racist fantasies while simultaneously being denied sexual agency. Disabled bodies have been desexualized or fetishized rather than recognized as fully human. Trans and gender-nonconforming people have had their bodies pathologized and their desires questioned. Decolonizing desire means naming these specific harms while creating new possibilities for pleasure that affirm the full humanity and desirability of all bodies. Cultural practices around beauty, attraction, and relationship formation often reflect colonial values rather than universal truths. The prioritization of youth, thinness, whiteness, and able-bodiedness as markers of desirability serves specific economic and political interests. By questioning these standards and cultivating appreciation for diverse forms of beauty and embodiment, we challenge the systems that profit from body shame and hierarchies of desirability. This doesn't mean denying personal preferences but examining how those preferences have been shaped and whether they serve our genuine fulfillment. Decolonizing desire extends beyond individual healing to transforming how communities understand and practice intimacy. Many indigenous and pre-colonial cultures embraced diverse gender expressions, relationship structures, and sexual practices that were systematically suppressed through colonization. Reclaiming these traditions—not through appropriation but through respectful learning and cultural revitalization—offers alternatives to the restrictive models of gender, sexuality, and relationship that dominate contemporary society. These alternative traditions remind us that current norms are neither universal nor inevitable but specific cultural formations that can be transformed.

Chapter 5: Harm Reduction: Pragmatic Approaches to Pleasure and Risk

Harm reduction offers a pragmatic, compassionate approach to pleasure that acknowledges reality rather than imposing moralistic ideals. Originally developed in response to drug use and HIV prevention, harm reduction principles recognize that people will seek pleasure—whether through substances, sex, food, or other means—and focuses on minimizing potential harms rather than demanding abstinence. This approach respects individual autonomy while providing information and resources that allow people to make informed choices about their pleasure practices. By rejecting shame and stigma, harm reduction creates space for honest conversation about both the benefits and risks of various pleasure-seeking behaviors. Applied to sexuality, harm reduction means developing practices that maximize pleasure and connection while minimizing unwanted outcomes like sexually transmitted infections, unwanted pregnancy, or emotional harm. This includes accessible education about sexual health, widespread availability of protection methods, and creating cultures that normalize communication about boundaries, desires, and safer sex practices. Rather than relying on fear-based messaging or promoting abstinence, sexual harm reduction empowers people to make choices aligned with their own values and risk assessments. This approach recognizes sexual pleasure as a legitimate goal rather than treating it as inherently dangerous or immoral. For substance use, harm reduction involves strategies like drug checking, dose awareness, understanding interactions between substances, creating supportive environments, and ensuring access to medical care without judgment. This approach acknowledges that substances can provide genuine benefits—from pain relief to enhanced connection to spiritual insight—while also carrying potential risks that can be mitigated through education and support. Harm reduction challenges the criminalization of certain substances, recognizing how drug prohibition has disproportionately harmed communities of color while failing to address problematic use. Instead, it advocates for evidence-based approaches that center health and wellbeing rather than punishment. Harm reduction also applies to food and body practices, challenging both diet culture and uncritical "body positivity" by focusing on wellbeing rather than appearance or moral virtue. This means developing a relationship with food based on nourishment, satisfaction, and cultural connection rather than restriction or numbing. It involves finding movement practices that bring genuine pleasure rather than punishment for having the "wrong" body. By rejecting shame around eating and embodiment, harm reduction creates space for more authentic relationships with food and movement that support overall wellbeing. For marginalized communities, harm reduction takes on additional significance as a response to systemic injustice. When certain groups face criminalization, stigma, or lack of resources around their pleasure practices, harm reduction becomes a form of resistance. Sex workers developing safety protocols, queer communities creating consent cultures, or people who use drugs establishing needle exchanges all represent harm reduction as community care in the face of institutional neglect or violence. These grassroots approaches demonstrate how communities can protect each other when systems fail to provide support or actively cause harm.

Chapter 6: Consent Culture: Creating Conditions for Authentic Connection

Authentic consent goes far beyond the minimal standard of "no means no" to create conditions where enthusiastic, informed "yes" becomes possible. This requires dismantling power dynamics that make genuine consent difficult or impossible—including economic coercion, racial hierarchies, gender socialization, and institutional authority. Rather than viewing consent as a one-time transaction, this framework recognizes it as an ongoing process of communication, attunement, and mutual care that creates the foundation for meaningful connection. Consent becomes not just an ethical requirement but a practice that enhances pleasure and intimacy by ensuring all participants are genuinely present and engaged. Developing consent culture begins with understanding our own desires, boundaries, and signals. Many people, particularly those socialized as women or raised in authoritarian contexts, have been taught to ignore their own discomfort and prioritize others' needs. Reclaiming the ability to recognize and honor our internal "yes" and "no" is therefore a crucial first step. This self-awareness allows us to communicate more clearly with others and recognize when external pressures are overriding our authentic responses. Practices like meditation, somatic awareness, and supportive community feedback help develop this internal clarity. Creating conditions for consent also requires addressing the ways trauma impacts our capacity for clear communication and boundary-setting. Many people have experienced violations that make it difficult to voice discomfort or assert needs in the moment. Trauma-informed consent practices acknowledge these realities, creating multiple pathways for communication, checking in regularly, and recognizing that consent may be withdrawn at any point. This approach prioritizes everyone's safety and agency rather than treating consent as a formality. By normalizing ongoing communication, consent culture makes space for the complexity of human desire and response. Beyond individual interactions, building consent culture involves transforming the social contexts in which we relate to each other. This includes challenging media representations that romanticize boundary violations, developing comprehensive sexuality education that centers ethics and communication, and creating community accountability processes that address harm without relying exclusively on punitive systems. These broader changes support individuals in practicing consent by shifting cultural norms and expectations. When consent becomes the standard rather than the exception, everyone benefits from clearer communication and more authentic connection. Importantly, consent isn't merely about avoiding harm but about creating conditions for genuine pleasure and connection. When we know our boundaries will be respected, we can more fully surrender to experiences of joy, vulnerability, and intimacy. When we trust that others are engaging with us authentically rather than from obligation or coercion, we can truly see and be seen by them. This mutual recognition forms the basis for connections that nourish rather than deplete us. Consent culture thus transforms interactions from potential sites of violation into opportunities for genuine exchange and mutual flourishing.

Chapter 7: Sustainable Movements: Integrating Pleasure into Liberation Work

Effective movement building requires sustainability, and pleasure activism offers crucial insights for creating social change work that nourishes rather than depletes participants. Traditional activist cultures often valorize sacrifice, urgency, and burnout—approaches that ultimately undermine long-term effectiveness and reproduce the very exploitation they seek to challenge. By contrast, pleasure-centered organizing recognizes that how we work is as important as what we're working toward, and that movements that feel good are more likely to succeed and endure. This doesn't mean avoiding difficult conversations or challenging work, but rather ensuring that the process itself contains elements of joy, connection, and satisfaction. Incorporating pleasure into movement spaces begins with meeting basic bodily needs—ensuring access to rest, nourishment, physical comfort, and accommodations for different bodies and abilities. Beyond these fundamentals, pleasure activism encourages practices that cultivate joy and connection: opening meetings with check-ins that acknowledge participants as whole people, incorporating music and movement, celebrating victories regardless of size, and creating space for genuine relationships to develop. These elements aren't superficial additions but essential components of sustainable organizing that prevent burnout and maintain long-term commitment. Pleasure activism also transforms how we approach strategy and vision. Rather than organizing primarily against what we oppose, this approach invites us to articulate and embody what we desire. What would justice feel like in our bodies? What sensations, relationships, and experiences do we want more of? By orienting around these positive visions, we generate more creative, compelling alternatives to current systems. This "yes" becomes a powerful complement to "no," offering not just resistance but redirection toward life-affirming possibilities. When movements can articulate and embody the world they're working to create, they become more attractive and accessible to potential participants. The integration of pleasure into movement work particularly benefits communities facing multiple forms of marginalization. When people who have been systematically denied access to rest, care, and joy prioritize these experiences within their organizing, they directly challenge dehumanizing systems that treat certain bodies as expendable. The insistence on pleasure becomes itself a form of resistance, asserting the right to thrive rather than merely survive. This approach recognizes that for those most impacted by oppression, experiencing joy and connection isn't a luxury but a necessity for continued resistance. Pleasure activism also offers tools for navigating conflict and difference within movements. By developing practices that help us stay present with discomfort without shutting down or lashing out, we can engage more honestly across lines of privilege and oppression. This doesn't mean avoiding difficult conversations but approaching them with an understanding that genuine connection and accountability feel better in the long run than superficial harmony or unaddressed harm. When movements create cultures that can hold both celebration and accountability, they become more resilient and effective at addressing internal dynamics that often undermine collective work.

Summary

The revolutionary potential of pleasure activism lies in its fundamental reframing of liberation work. By positioning pleasure not as a reward that comes after freedom is achieved but as both the means and the end of liberation, it transforms how we understand resistance itself. This framework doesn't diminish the seriousness of justice work but rather expands our conception of what sustainable transformation requires. When we recognize that our capacity for joy, connection, and embodied satisfaction constitutes an essential resource rather than a luxury, we access deeper wells of resilience and creativity for the long struggle toward collective liberation. The most profound insight offered through this exploration is that pleasure—authentic, embodied, consensual pleasure—provides not just motivation for justice work but a compass for navigating it. When we ask "Does this bring genuine satisfaction? Does this honor our capacity for joy? Does this expand our sense of possibility?" we develop more reliable guidance than abstract ideology alone can provide. This doesn't mean avoiding difficulty or discomfort, as growth often requires moving through challenging emotions and experiences. Rather, it means approaching even the hardest aspects of liberation work with an orientation toward life, connection, and possibility rather than martyrdom, isolation, or despair.

Best Quote

“I believe that all organizing is science fiction - that we are shaping the future we long for and have not yet experienced.” ― Adrienne Maree Brown, Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good

Review Summary

Strengths: The book's structure and organization are praised for preventing reader saturation by spacing out different mediums. It is noted for being inclusive, featuring contributions from women, gender non-conforming, and trans people of color. The diversity of backgrounds among contributors, ranging from art and performance to activism, makes the book accessible to a broad audience. Weaknesses: The reviewer expected a broader discussion on making social justice pleasurable but found the book predominantly focused on sexual pleasure and relationships. This discrepancy between expectation and content is highlighted as a limitation. Overall Sentiment: Mixed Key Takeaway: While "Pleasure Activism" is well-organized and inclusive, its primary focus on sexual pleasure may not align with all readers' expectations of a broader discourse on pleasurable social justice.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.