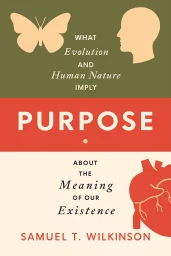

Purpose

What Evolution and Human Nature Imply about the Meaning of Our Existence

Categories

Nonfiction, Science

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2024

Publisher

Pegasus Books

Language

English

ISBN13

9781639365173

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Purpose Plot Summary

Introduction

For over a century, science and religion have been portrayed as fundamentally incompatible worldviews, locked in an eternal struggle for intellectual supremacy. This false dichotomy has forced many to choose between scientific understanding and spiritual meaning, as if embracing one necessarily meant rejecting the other. The debate reached a symbolic peak during the infamous Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925, when evolution became the battleground for this larger cultural conflict. Since then, the narrative that evolutionary theory eliminates purpose from human existence has persisted, leading many to conclude that if humans evolved through natural processes, our lives must be devoid of inherent meaning. This unnecessary conflict has profound consequences. When scientific materialism is presented as the only rational worldview, it often leaves people struggling with existential questions that science alone cannot answer. Meanwhile, religious perspectives that reject established scientific findings appear increasingly untenable in our modern age. The reconciliation of these seemingly opposing perspectives requires a deeper examination of what evolutionary science actually reveals about human nature. By carefully analyzing convergent evolution, the biological foundations of altruism, the dual nature of human behavior, and the evidence for genuine free will, we can discover that evolutionary theory, properly understood, does not eliminate purpose but may actually provide a scientific foundation for it.

Chapter 1: The False Dichotomy Between Science and Religion

For over a century, science and religion have been portrayed as fundamentally incompatible worldviews, locked in an eternal struggle for intellectual supremacy. This false dichotomy has forced many to choose between scientific understanding and spiritual meaning, as if embracing one necessarily meant rejecting the other. The debate reached a symbolic peak during the infamous Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925, when evolution became the battleground for this larger cultural conflict. Since then, the narrative that evolutionary theory eliminates purpose from human existence has persisted, leading many to conclude that if humans evolved through natural processes, our lives must be devoid of inherent meaning. This unnecessary conflict has profound consequences. When scientific materialism is presented as the only rational worldview, it often leaves people struggling with existential questions that science alone cannot answer. Meanwhile, religious perspectives that reject established scientific findings appear increasingly untenable in our modern age. The reconciliation of these seemingly opposing perspectives requires a deeper examination of what evolutionary science actually reveals about human nature. By carefully analyzing convergent evolution, the biological foundations of altruism, the dual nature of human behavior, and the evidence for genuine free will, we can discover that evolutionary theory, properly understood, does not eliminate purpose but may actually provide a scientific foundation for it. The historical roots of this conflict trace back to interpretations of Darwin's theory that emphasized randomness and purposelessness. When evolution was characterized primarily as a process of random mutation and survival of the fittest, it seemed to leave no room for divine guidance or inherent meaning. As Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson declared: "If humankind evolved by Darwinian natural selection, genetic chance and environmental necessity, not God, made the species." This perspective created an apparent contradiction between accepting evolutionary science and believing in a purposeful universe. However, this dichotomy rests on outdated and incomplete understandings of evolutionary processes. Modern evolutionary biology reveals patterns and principles that suggest evolution is far more structured and directional than previously thought. The phenomenon of convergent evolution—where similar traits evolve independently in unrelated species—indicates that physical and biological constraints channel evolutionary pathways toward predictable outcomes. This suggests that evolution follows inherent principles rather than proceeding through purely random processes. The reconciliation of science and religion requires moving beyond simplistic either/or thinking to recognize that evolutionary mechanisms can be understood as the means through which higher purposes unfold. As evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky wrote: "It is wrong to hold creation and evolution as mutually exclusive alternatives. I am a creationist and an evolutionist. Evolution is God's, or Nature's, method of Creation." This integrated perspective allows us to embrace both scientific understanding and the search for meaning without sacrificing intellectual integrity.

Chapter 2: Evolution as a Guided Process, Not Random Chance

Contrary to popular belief, evolution is not fundamentally a random process. While genetic mutations may occur randomly, the overall trajectory of evolution shows remarkable patterns of convergence across independent lineages. Consider the striking similarities between dolphins and sharks, despite their vastly different evolutionary origins. Both developed streamlined bodies, dorsal fins, and similar swimming mechanisms because these features represent optimal solutions for marine locomotion. Similarly, eyes have evolved independently at least 40 times across different animal groups, with camera-type eyes appearing in creatures as diverse as humans, octopuses, and box jellyfish. This phenomenon, known as convergent evolution, occurs because physical and biological constraints limit the possible forms that can emerge. When we examine the "skeleton space" of all theoretically possible body plans, we find that only a small subset are actually viable in our universe. The laws of physics, chemistry, and mathematics create boundary conditions that channel evolution toward certain outcomes. Like water flowing downhill that must follow the contours of the landscape, evolution follows paths of least resistance toward functional solutions. The implications of this guided process are profound. If we could "rewind the tape of life" and let evolution play out again, we would likely see similar patterns emerge. This suggests that humans, or at least human-like intelligence, may be an inevitable outcome of evolution rather than a cosmic accident. The renowned paleontologist Simon Conway Morris argues that the ubiquity of convergence indicates that evolution is far more predictable and constrained than previously thought. Furthermore, the emergence of complexity in biological systems follows mathematical principles that appear built into the fabric of reality itself. From the spiral patterns of shells to the branching structures of lungs and trees, we see the same mathematical relationships appearing repeatedly. These patterns emerge not through random chance but through the interaction of natural laws with living systems. This suggests that the universe contains inherent tendencies toward certain forms of order and complexity. This view of evolution as a guided process does not require supernatural intervention at each step. Rather, it suggests that the laws of nature themselves contain the seeds of biological complexity and even consciousness. Evolution may be the mechanism through which inherent potentials in the universe unfold, following trajectories that were implicit in the initial conditions of our cosmos.

Chapter 3: The Dual Nature of Human Behavior

Human behavior exhibits a remarkable duality that has puzzled philosophers and scientists for centuries. We are capable of extraordinary altruism, compassion, and cooperation, yet we also demonstrate selfishness, aggression, and cruelty. This paradox becomes comprehensible when viewed through an evolutionary lens that recognizes multiple selection pressures operating simultaneously on human populations throughout our evolutionary history. Individual selection favors traits that increase personal survival and reproduction, often promoting self-interested behaviors. When resources are scarce, individuals who secure more for themselves and their immediate offspring have a reproductive advantage. This explains our capacity for selfishness, status-seeking, and competitive behaviors. Yet humans also evolved in highly social groups where cooperation was essential for survival. Group selection pressures favored traits that enhanced collective success, even when they occasionally reduced individual fitness. Groups with more altruistic, cooperative members outcompeted groups composed of purely selfish individuals. Kin selection further complicates this picture by favoring behaviors that benefit genetic relatives. Hamilton's rule mathematically demonstrates how altruistic behaviors can evolve when the cost to the individual is outweighed by the benefit to relatives multiplied by their degree of genetic relatedness. This explains why humans feel strongest altruistic impulses toward family members, with diminishing intensity as genetic relatedness decreases. Yet human altruism extends beyond kin to include reciprocal relationships with non-relatives and even generalized altruism toward strangers. The tension between these competing evolutionary pressures has resulted in a species with remarkable behavioral flexibility. We possess neural circuitry that supports both selfish and altruistic impulses, with cultural and environmental factors influencing which tendencies predominate in any given situation. This explains why humans can exhibit such dramatic variations in behavior across different contexts and cultures. The same person who acts selfishly in a competitive business environment might demonstrate extraordinary generosity within their family or community. This dual nature is not a design flaw but an adaptive feature that allowed our ancestors to navigate complex social environments while maintaining individual fitness. It enables humans to form the cooperative social structures necessary for civilization while retaining the individual drive that fuels innovation and adaptation. Understanding this evolutionary heritage helps explain the moral struggles we experience and the ethical systems we develop to manage our competing impulses.

Chapter 4: Free Will and Moral Choice in Evolutionary Context

The question of whether humans possess genuine free will has profound implications for how we understand moral responsibility. Some scientists and philosophers argue that if our thoughts and actions are determined by physical processes in our brains, which in turn are shaped by genetics and environment, then free will must be an illusion. This deterministic view suggests that our sense of making choices is merely an epiphenomenon—a story our consciousness tells itself after decisions have already been made by unconscious neural processes. However, this simplistic determinism fails to account for the emergent properties that arise at different levels of complexity. Just as water molecules exhibit properties not predictable from hydrogen and oxygen atoms alone, human consciousness and decision-making cannot be reduced to the firing of individual neurons. The brain operates as a complex, dynamic system with inherent indeterminacy. Neuroscientists have observed that identical stimuli do not produce identical neural responses, suggesting that the brain incorporates genuine unpredictability at multiple levels. Moreover, experimental evidence demonstrates that conscious intentions can causally influence behavior. Studies of implementation intentions show that deliberate planning significantly affects future actions, even when controlling for other variables. Mental practice demonstrably improves physical performance in sports and music, proving that conscious mental states can affect motor skills. These findings contradict the epiphenomenalist view that consciousness is merely a passive observer of predetermined actions. The much-cited Libet experiments, often used to argue against free will, actually reveal the limitations of studying simple, arbitrary decisions like when to flex a wrist. Such trivial choices bear little resemblance to the morally significant decisions that define our character and shape our lives. When we deliberate about important life choices, we engage in extended processes of conscious reasoning, emotional evaluation, and value assessment that cannot be reduced to unconscious neural activity preceding awareness. From an evolutionary perspective, the capacity for genuine choice would confer significant adaptive advantages. Organisms that can flexibly respond to novel situations, learn from experience, and inhibit automatic responses would outcompete those locked into rigid behavioral patterns. The human capacity for moral reasoning and choice may represent the most sophisticated expression of this evolutionary trend toward behavioral flexibility and self-regulation. This evolutionary account of free will aligns with our lived experience of making choices and being held accountable for them. It suggests that while our options and inclinations are constrained by biology and circumstance, we possess genuine agency within those constraints. This capacity for choice, combined with our dual nature, creates the conditions for moral development and ethical progress.

Chapter 5: Family and Relationships as Evolutionary Adaptations

Human relationships, particularly family bonds, represent some of the most powerful forces shaping our emotional lives and social behaviors. Far from being cultural constructs superimposed on our biology, these relationship patterns reflect deep evolutionary adaptations that facilitated survival and reproduction in our ancestral environment. Understanding the evolutionary roots of human attachment illuminates why relationships are so fundamental to our well-being and moral development. The parent-child bond represents perhaps the most fundamental relationship pattern in human psychology. Human infants are born remarkably helpless compared to other primates, requiring years of intensive care before achieving independence. This extended period of dependency created strong selection pressures for attachment mechanisms that would ensure parental investment. Infants evolved behaviors—crying, smiling, cooing—specifically designed to elicit caregiving responses, while parents evolved complementary neural systems that make responding to these signals intrinsically rewarding. The work of attachment theorists like John Bowlby demonstrated that these early bonds form templates for all subsequent relationships and significantly impact psychological development. Romantic attachment between adults evolved as an extension of these same attachment mechanisms. The human capacity for pair-bonding and long-term mating relationships represents an evolutionary solution to the challenge of raising highly dependent offspring. Monogamous partnerships allowed for greater paternal investment, which improved offspring survival in resource-scarce environments. The neurobiological systems underlying romantic love—involving oxytocin, dopamine, and endorphins—create powerful emotional experiences that motivate long-term commitment and cooperation between partners. Broader social relationships beyond the nuclear family also show clear evolutionary signatures. Humans evolved in small, interdependent groups where cooperation was essential for survival. This created selection pressures for social emotions like empathy, gratitude, and guilt that facilitate group cohesion. The human brain devotes significant resources to social cognition, allowing us to track complex relationships and navigate group dynamics. Studies consistently show that social integration strongly predicts physical health, psychological well-being, and longevity. These evolutionary adaptations explain why relationships are so central to human happiness and moral development. When longitudinal research like the Harvard Study of Adult Development followed participants for over 75 years, the quality of relationships emerged as the strongest predictor of health and well-being—stronger than wealth, fame, or professional success. This finding makes perfect evolutionary sense: our ancestors' survival depended on forming and maintaining strong social bonds. The evolutionary perspective also explains why family disruption can have such profound psychological impacts. When attachment bonds are broken or never properly formed, individuals often experience significant distress and developmental challenges. This biological reality has important implications for social policy and personal decision-making regarding family formation and stability.

Chapter 6: From Selfishness to Altruism: Nature's Hidden Purpose

The evolution of altruism represents one of the most profound transitions in the history of life on Earth. While natural selection initially appears to favor selfishness, closer examination reveals multiple mechanisms through which genuinely altruistic behaviors can evolve. These mechanisms collectively suggest that cooperation and altruism are not accidents but integral features of evolutionary processes, particularly in social species like humans. Kin selection provides the most straightforward evolutionary pathway to altruism. When individuals help genetic relatives, they indirectly promote the survival of shared genes. This explains why parents willingly sacrifice for children and why siblings typically show greater mutual aid than unrelated individuals. Hamilton's rule mathematically demonstrates how such behaviors can evolve when the benefit to the recipient, multiplied by the degree of genetic relatedness, exceeds the cost to the altruist. Reciprocal altruism extends cooperative behavior beyond genetic relatives. When individuals interact repeatedly over time, helping behaviors can evolve if recipients reciprocate in the future. This creates systems of mutual aid that benefit all participants over the long term. The evolution of emotions like gratitude, guilt, and moral indignation helps stabilize these reciprocal relationships by motivating individuals to uphold cooperative norms. Reputation-based or indirect reciprocity further expands the scope of altruism. In social groups where information about individuals' behavior spreads, developing a reputation for generosity can bring future benefits from third parties. This creates selection pressures for public displays of altruism and explains why humans are particularly generous when observed by others. The desire for social approval thus becomes an evolutionary mechanism promoting genuinely helpful behaviors. Perhaps most surprisingly, group selection may have played a significant role in human evolution. Groups composed of more altruistic individuals often outcompete groups of selfish individuals, especially during intergroup competition. This creates selection pressures at the group level that can override individual-level selection for selfishness. Mathematical models demonstrate that under certain conditions—particularly those that characterized human evolutionary history—group selection can drive the evolution of genuine altruism. These evolutionary pathways to altruism are reinforced by the intrinsic rewards humans experience when helping others. Multiple studies show that acts of generosity activate reward centers in the brain, creating positive emotions that reinforce altruistic behavior. This "warm glow" of giving appears to be a built-in feature of human psychology, suggesting that natural selection has wired us to find cooperation inherently satisfying. The evolutionary emergence of altruism suggests a trajectory in nature from simple self-interest toward increasingly complex forms of cooperation. This trajectory appears to be built into the logic of evolution itself, particularly for social species. Far from being a random process devoid of direction, evolution seems to contain inherent tendencies toward greater cooperation, complexity, and even moral development.

Chapter 7: Implications for Finding Meaning in a Scientific Age

The integration of evolutionary science with questions of purpose and meaning offers a powerful framework for addressing the existential challenges of our time. By recognizing that evolution is not a random, purposeless process but a guided one that has produced beings capable of moral choice, we can develop a worldview that honors both scientific understanding and the human search for meaning. This integrated perspective suggests that the capacity for moral development is not accidental but integral to human nature. Our dual tendencies toward both selfishness and altruism create the conditions for genuine moral choice. We are not merely executing genetically programmed behaviors but navigating between competing impulses with the capacity to choose which aspects of our nature to cultivate. This freedom within constraints aligns with our lived experience of moral struggle and growth. The evolutionary importance of relationships provides scientific grounding for what many spiritual traditions have long emphasized: that connection with others constitutes a central purpose of human existence. The fact that our brains and bodies are literally designed to form attachments, experience empathy, and derive satisfaction from helping others suggests that these relational capacities represent core features of human flourishing, not cultural constructs or subjective preferences. This perspective also offers a path beyond the nihilism that sometimes accompanies materialist worldviews. If evolution has shaped us to find meaning in relationships, moral development, and contribution to others, then these sources of meaning have objective foundations in our biology. The sense of purpose we derive from them is not merely a subjective illusion but a reflection of our evolutionary heritage and the actual trajectory of life on Earth. For individuals seeking meaning in a scientific age, this framework suggests practical implications. It validates the importance of cultivating close relationships, particularly family bonds, as central to well-being. It encourages the development of communities that support our better nature while helping us resist our selfish impulses. And it suggests that moral growth—the journey from selfishness toward greater altruism—represents a fundamental human purpose aligned with the larger patterns of evolutionary development. Perhaps most importantly, this perspective allows us to see ourselves as participants in an ongoing evolutionary process with an inherent direction. Rather than viewing humans as accidental byproducts of random mutations, we can understand ourselves as expressions of nature's tendency toward greater complexity, consciousness, and cooperation. Our capacity for moral choice and altruistic love may represent not aberrations in a meaningless universe but the fulfillment of potentials built into the fabric of reality itself.

Summary

The reconciliation of evolutionary science with human purpose reveals that the apparent conflict between these domains stems from misunderstanding rather than inherent incompatibility. When we examine evolution more carefully, we discover a process that is far from random—it is channeled by physical laws and mathematical principles toward predictable outcomes. The ubiquity of convergent evolution suggests that human-like intelligence may be an inevitable result of evolutionary processes rather than a cosmic accident. Similarly, our capacity for altruism, moral choice, and deep relationships appears to be built into our biology through multiple evolutionary mechanisms, including kin selection, reciprocal altruism, and possibly group selection. This integrated perspective transforms how we understand human nature and purpose. Rather than seeing ourselves as passive products of blind forces, we can recognize ourselves as beings evolved with the capacity for genuine choice between competing tendencies. Our evolutionary heritage has equipped us with both selfish and altruistic impulses, creating the conditions for moral development. The fact that relationships and altruistic behavior are intrinsically rewarding suggests that connection and moral growth represent fundamental human purposes aligned with our biological nature. This framework offers a path beyond both religious fundamentalism that rejects science and scientific materialism that dismisses purpose, toward a more complete understanding that honors both empirical evidence and the human search for meaning.

Best Quote

“hours have passed without you noticing. • Meaning. According to Seligman, this involves “belonging to and serving something that you believe is bigger than the self.”25 Meaning is almost always tied to how we interact with others.26 • Accomplishment. This often involves doing things just for the sake of doing them. It can satisfy important needs, but taken to extremes it can also lead to a deterioration of personal relationships. • Positive Relationships. These, again, are just what you think they are: warm and nurturing relationships, especially with close friends and family, which give us a sense of peace, happiness, security, and well-being.” ― Samuel T. Wilkinson, Purpose: What Evolution and Human Nature Imply about the Meaning of Our Existence

Review Summary

Strengths: The book presents interesting arguments that suggest the compatibility of belief in God with the theory of evolution. It is described as a fascinating read that fundamentally changed the reviewer's perspective on leveraging evolutionary knowledge for human benefit. The book is also noted for its enjoyable and thought-provoking content, warranting a re-read.\nWeaknesses: The section on free will is perceived as somewhat lacking. Additionally, the book's attempt to reconcile evolution with religious beliefs is met with skepticism by some readers, particularly those with strong atheistic views or creationist beliefs.\nOverall Sentiment: Mixed. While the book is appreciated for its intriguing arguments and readability, it also faces criticism from both atheistic and creationist perspectives.\nKey Takeaway: The book attempts to bridge the gap between religious belief and scientific understanding of evolution, offering a perspective that may appeal to those open to integrating these views, though it may not convince staunch atheists or creationists.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.