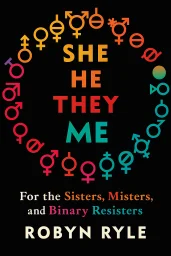

She/He/They/Me

For the Sisters, Misters, and Binary Resisters

Categories

Business, Nonfiction, Psychology, Leadership, Feminism, Sociology, Adult, Gender, LGBT

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

0

Publisher

Sourcebooks

Language

English

ASIN

1492666947

ISBN

1492666947

ISBN13

9781492666943

File Download

PDF | EPUB

She/He/They/Me Plot Summary

Introduction

Imagine waking up one day to find that the concept of gender as you know it has completely transformed. The neat categories of "male" and "female" have dissolved, replaced by a spectrum of possibilities that extend far beyond what you've been taught. This scenario isn't science fiction—it's already happening in societies around the world as our understanding of gender evolves at an unprecedented pace. Gender shapes nearly every aspect of our lives, from the clothes we wear to the careers we pursue, yet most of us rarely pause to examine its fundamental nature. Is gender something we're born with or something society creates? Why do different cultures have such varied gender systems? And how might our lives be different if we weren't constrained by rigid gender expectations? This book takes you on a journey through the complex landscape of gender identity, exploring how biology, psychology, and culture interact to create our sense of who we are. You'll discover surprising variations in gender expression across different societies, learn how binary thinking limits human potential, and gain insight into how gender intersects with other aspects of identity to create unique lived experiences.

Chapter 1: The Social Construction of Gender Assignment

Gender assignment happens the moment someone declares "It's a boy!" or "It's a girl!" at birth, but this seemingly simple act launches a lifelong process of social categorization. While many people assume gender is determined solely by biological sex, social scientists understand gender primarily as a social construct—a set of meanings, expectations, and roles that societies create and reinforce through everyday interactions. These constructions vary dramatically across cultures and throughout history, revealing that what seems "natural" in one context may be completely foreign in another. The social construction of gender begins with assignment but continues throughout our lives through a process called gender socialization. From the moment of birth, we receive different treatment based on our assigned gender. Parents speak more gently to infants perceived as girls, encourage more physical play with those perceived as boys, and select gender-coded toys, clothes, and activities that reinforce societal expectations. These small differences accumulate over time, shaping everything from our communication styles to our emotional expression. What's particularly fascinating is how gender constructions differ across cultures. In Western societies, gender has traditionally been conceptualized as a strict binary, but many indigenous cultures recognize three, four, or even five gender categories. The Navajo recognize nádleehí (those who transform), while in India, hijras occupy a distinct gender category with specific social and spiritual roles. These examples demonstrate that our Western binary understanding is just one of many possible gender systems, not a universal truth. The medicalization of gender assignment reveals much about how deeply entrenched binary thinking has become in Western society. When intersex infants are born with ambiguous genitalia, many medical professionals recommend immediate surgical intervention to align the child's body with either male or female categories. This practice prioritizes social conformity over the child's bodily autonomy and future gender identity, demonstrating how powerful the impulse to maintain gender boundaries can be. The social construction of gender doesn't mean biological factors are irrelevant—rather, it highlights how biology is interpreted through cultural lenses. The same biological traits might be emphasized in one culture and ignored in another. Understanding gender as socially constructed opens up possibilities for reimagining gender in ways that allow for greater individual expression and social equality, recognizing that what we consider "natural" about gender is often simply what we've been taught to see.

Chapter 2: Gender Identity vs. Gender Expression

Gender identity and gender expression represent two distinct but related aspects of how we experience and communicate gender. Gender identity refers to one's internal, deeply felt sense of being male, female, both, neither, or somewhere in between—it's who you know yourself to be. Gender expression, by contrast, encompasses how you present your gender to the world through clothing, hairstyle, mannerisms, and other external characteristics. While these two dimensions often align in ways society expects, they can also diverge significantly. The relationship between identity and expression is complex and multidirectional. For cisgender people (those whose gender identity matches their assigned sex at birth), the alignment between internal identity and external expression may feel natural and unremarkable. However, for transgender and gender non-conforming individuals, navigating the gap between internal identity and societal expectations can be challenging. A transgender woman may have always known herself to be female (identity) long before she could safely express that identity through feminine presentation (expression). Similarly, a cisgender man might express himself in ways society codes as feminine without questioning his male identity. Cultural contexts dramatically influence what constitutes "appropriate" gender expression. In contemporary American culture, women wearing pants is unremarkable, but this represents a significant historical shift in gender expression norms. In other cultures, what Westerners might consider gender-crossing expressions are perfectly acceptable—men in Scotland wear kilts, men in many Middle Eastern and North African countries hold hands as friends, and pink was considered a masculine color in early 20th century America. These variations reveal how arbitrary many of our assumptions about "natural" gender expression truly are. Gender expression often serves as a social signal through which we communicate our identities to others, but this communication isn't always received as intended. Someone might express their gender in ways that feel authentic to them, only to have others misinterpret these signals based on their own cultural assumptions. This mismatch between intended and perceived gender expression can create significant challenges, particularly for gender non-conforming individuals who may face discrimination or violence when their expression challenges social expectations. The relationship between identity and expression becomes particularly fascinating when we consider how they influence each other over time. While identity often drives expression, sometimes exploring different forms of expression can lead to discoveries about identity. A person assigned female at birth might experiment with masculine clothing initially as a form of expression, only to realize through this exploration that their gender identity itself doesn't align with their birth assignment. This dynamic interplay highlights the fluid, evolving nature of gender as both an internal experience and a social interaction.

Chapter 3: Intersex and the Biological Spectrum

Intersex conditions represent perhaps the clearest evidence that biological sex exists on a spectrum rather than as a binary. The term "intersex" encompasses dozens of conditions where a person is born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn't fit neatly into conventional definitions of male or female. These variations can appear in chromosomes, gonads, hormone production, hormone response, and/or genital anatomy, creating biological realities that challenge our binary thinking about sex and gender. The frequency of intersex conditions is much higher than most people realize. Conservative estimates suggest that roughly 1.7% of the population is born with intersex traits—similar to the percentage of people born with red hair. This comparison helps illustrate that intersex variations are natural, common aspects of human diversity rather than rare abnormalities. Some intersex conditions are visible at birth, such as ambiguous genitalia, while others might only become apparent during puberty or remain undiscovered throughout a person's life. The medical treatment of intersex infants reveals much about society's investment in maintaining gender boundaries. Historically, when babies were born with ambiguous genitalia, doctors often performed immediate "normalizing" surgeries to assign them to one sex or another, frequently without full disclosure to parents about alternatives. These interventions weren't medically necessary—most intersex conditions pose no health risk—but were justified as preventing potential psychological distress. However, many intersex adults who underwent such surgeries as infants report physical complications, psychological trauma, and grief over having bodily autonomy violated before they could consent. Intersex advocacy has led to significant shifts in medical approaches over recent decades. Organizations like InterACT advocate for a patient-centered model that delays non-essential surgeries until individuals can participate in decisions about their own bodies. This approach recognizes that gender identity development is complex and can't be predicted by surgical intervention. Countries including Malta and Portugal have passed legislation banning medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex infants, acknowledging these procedures as human rights violations. The existence of intersex conditions fundamentally challenges binary thinking about sex and gender. If biology itself doesn't neatly divide humans into two distinct categories, then social systems built on this binary foundation require reconsideration. Intersex realities invite us to recognize that variation in sex characteristics is natural and normal, requiring neither medical "correction" nor social stigma. By embracing this biological diversity, we can create more inclusive understandings of gender that honor the full spectrum of human experience.

Chapter 4: Transgender Experiences and Medical Transitions

Transgender individuals have existed throughout human history and across cultures, though terminology and social acceptance have varied dramatically. Being transgender means having a gender identity that differs from the sex assigned at birth—a profound internal knowledge that societal assumptions about one's gender don't match one's authentic self. This recognition often emerges early in childhood, with many transgender people reporting they knew their gender differed from expectations as young as three or four years old, though others may discover or acknowledge their transgender identity later in life. The process of transition—aligning one's external presentation and sometimes physical characteristics with one's internal gender identity—varies significantly between individuals. Social transition typically involves adopting name, pronoun, clothing, and hairstyle changes that reflect one's gender identity. Medical transition may include hormone therapy to develop secondary sex characteristics aligned with one's gender (such as breast development or facial hair growth) and various surgical interventions. However, not all transgender people desire or pursue medical transition, and the specific aspects of transition each person seeks are deeply personal decisions. For those who do pursue medical transition, access to care remains a significant challenge. Transgender healthcare has historically operated under a "gatekeeping" model requiring psychological evaluation and diagnosis before accessing medical interventions. While intended to ensure appropriate care, this model has often created barriers for transgender individuals who know themselves best. More recently, informed consent models have emerged, recognizing transgender people's autonomy in making decisions about their own bodies. However, financial barriers persist, as insurance coverage for transgender healthcare remains inconsistent, and many procedures are prohibitively expensive without coverage. The lived experiences of transgender people reveal both profound personal journeys and the impact of societal attitudes. Many transgender individuals describe the relief and authenticity they feel when living as their true gender, often referred to as "gender euphoria." Conversely, "gender dysphoria" describes the distress that can arise from the mismatch between one's gender identity and physical characteristics or social treatment. Research consistently shows that access to supportive environments and gender-affirming care significantly improves mental health outcomes for transgender people, with social support being particularly crucial for well-being. Transgender experiences also highlight how gender operates in society at large. When someone transitions, they often gain unique insight into how differently people are treated based on perceived gender. Trans women frequently report experiencing increased sexual harassment and diminished professional authority after transition, while trans men may notice their opinions carry more weight in professional settings. These experiences make visible the gender-based inequalities that often remain invisible to cisgender people, offering powerful evidence of how gender shapes social interactions regardless of individual characteristics.

Chapter 5: Gender and Sexuality: Complex Connections

Gender and sexuality are distinct aspects of identity that intersect in complex ways. While gender concerns who you are, sexuality concerns who you're attracted to emotionally, romantically, and/or sexually. Although these concepts are separate, they've been historically conflated in ways that continue to shape cultural understandings today. For instance, the early medical model of homosexuality in the late 19th century characterized gay men as having "inverted" gender identities—essentially viewing them as having female souls in male bodies—reflecting how tightly gender and sexual orientation were linked in professional and public imagination. This historical conflation continues to influence contemporary stereotypes. Gay men are often stereotyped as feminine, lesbian women as masculine, and bisexual people as confused or going through a phase. These stereotypes reveal the persistence of a heteronormative framework that assumes "proper" gender expression naturally leads to heterosexual attraction. Under this framework, same-sex attraction is interpreted as a kind of gender failure—if a woman is attracted to women, the logic goes, she must be "like a man" in some essential way. This thinking fails to recognize the diversity within LGBTQ+ communities, where gender expression varies as widely as it does among heterosexual people. The emergence of terminology beyond the traditional homosexual/heterosexual binary reflects growing recognition of sexuality's complexity. Terms like pansexual (attraction regardless of gender), demisexual (attraction only after emotional connection forms), and asexual (experiencing little or no sexual attraction) acknowledge that sexuality encompasses far more dimensions than just the gender of one's preferred partners. Similarly, the growing visibility of nonbinary and genderfluid identities challenges the assumption that attraction must be categorized in relation to a strict gender binary. Cross-cultural perspectives further illuminate the constructed nature of sexuality categories. Many indigenous cultures recognized same-sex relationships without constructing them as a distinct identity category. In ancient Greece, sexual relationships between men were common and accepted, but were structured around social status rather than gender—the relevant distinction was between the active and passive partner, not their genders. These examples demonstrate that Western categories of sexual orientation are cultural constructs rather than universal truths. The relationship between gender and sexuality becomes particularly complex for transgender and nonbinary individuals. A trans woman attracted to women might identify as a lesbian, while a nonbinary person might use terms like "queer" that allow for greater flexibility. The outdated assumption that gender identity should predict sexual orientation has often created additional barriers for transgender people seeking gender-affirming care, with some medical providers historically denying treatment to transgender people who didn't conform to heterosexual expectations post-transition. These experiences highlight how presumed connections between gender and sexuality can limit individual autonomy and self-determination.

Chapter 6: Gender Inequality in Work and Society

Gender inequality manifests in virtually every sphere of social life, from economic disparities to cultural representation, creating different lived experiences for people based on gender. One of the most persistent forms of inequality appears in the workplace, where the gender pay gap continues despite significant progress in women's educational attainment. In the United States, women earn approximately 82 cents for every dollar earned by men, with the gap widening significantly for women of color. This disparity stems from multiple factors, including occupational segregation (the concentration of women in lower-paying fields), differences in promotion rates, and penalties associated with motherhood. The "glass ceiling" describes invisible barriers preventing women from reaching the highest levels of organizational leadership, while the "sticky floor" keeps others trapped in the lowest-paying positions. These metaphors capture how gender inequality operates on multiple levels simultaneously. Interestingly, when men enter traditionally female-dominated professions, they often experience a "glass escalator" effect, rising more quickly to administrative positions than their female counterparts. This phenomenon highlights how gender valuation follows individuals across occupational boundaries rather than being strictly tied to the work itself. Unpaid domestic labor represents another critical dimension of gender inequality. Women globally perform significantly more unpaid work than men, including childcare, eldercare, cooking, cleaning, and emotional labor—the work of managing household relationships and well-being. This "second shift" limits women's capacity to participate equally in paid employment and leisure activities. The COVID-19 pandemic starkly revealed these disparities, as women disproportionately shouldered additional caregiving responsibilities when schools and childcare facilities closed, leading many to reduce hours or leave the workforce entirely. Media representation both reflects and reinforces gender inequality through stereotyped portrayals and unequal visibility. Women remain underrepresented in film and television, particularly in positions of authority, while being overrepresented in sexualized contexts. When women are portrayed in leadership roles, their appearance and family status typically receive scrutiny that male counterparts escape. Similarly, transgender and nonbinary people rarely see authentic representations of their experiences in mainstream media, contributing to societal misunderstanding and marginalization. Political power distributions continue to reflect gender inequality worldwide. Though women comprise roughly half the global population, they held only about 26% of parliamentary seats globally as of 2021. This underrepresentation impacts policy priorities, as research shows women legislators are more likely to champion issues like healthcare, education, and family leave. The intersection of gender with other aspects of identity further complicates political representation—women of color, transgender women, and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face compounded barriers to political participation and leadership.

Chapter 7: The Future of Gender: Evolution or Revolution?

The future of gender is already unfolding around us, with traditional frameworks being reimagined through both incremental evolution and revolutionary challenges to the status quo. Among younger generations, particularly Gen Z, we're witnessing unprecedented openness to gender diversity. Surveys consistently show these young adults are significantly more likely to identify as transgender or nonbinary than previous generations, reflecting not necessarily a change in human nature but a shift in what identities are socially legible and acceptable to claim. Technology is transforming gender expressions and communities in profound ways. Social media platforms have become crucial spaces for gender exploration, allowing individuals to find representation, community, and language for identities they might never encounter in their immediate environment. These digital spaces enable people to experiment with different gender presentations through avatars and personas before potentially bringing these expressions into their physical lives. Meanwhile, advances in medical technologies offer more options for physical transition, while virtual reality and augmented reality open possibilities for embodied experiences of gender that transcend physical limitations. Legal recognition for gender diversity is evolving rapidly, though unevenly, across the globe. Countries including Argentina, Denmark, and New Zealand have implemented gender self-determination laws allowing individuals to legally change their gender markers without medical requirements. Several jurisdictions now offer "X" or third-gender options on identification documents, acknowledging the existence of nonbinary identities. However, these progressive developments exist alongside backlash legislation targeting transgender rights in many regions, illustrating the contested nature of gender's future. The very structure of language is transforming to accommodate broader understandings of gender. English speakers increasingly adopt singular "they/them" pronouns for nonbinary individuals, while languages with more extensive grammatical gender are developing innovative solutions for gender-neutral expression. In Swedish, the gender-neutral pronoun "hen" has been officially incorporated into the language, while Spanish speakers experiment with endings like "-e" as alternatives to gendered "-o" and "-a" suffixes. These linguistic evolutions reflect how deeply gender is embedded in our communication systems and how creative adaptation can expand our capacity for expression. What remains unclear is whether the future will bring reform of existing gender systems or their fundamental transformation. Some advocate for expanding the current binary to include more options, creating a more inclusive but still categorized approach to gender. Others envision a post-gender future where personal expression exists on a spectrum of infinite possibilities without discrete categories at all. Most likely, we'll see multiple approaches developing simultaneously across different cultural contexts. What seems certain is that rigid binary conceptions of gender are giving way to more flexible, individualized understandings that prioritize personal authenticity over social conformity. The future of gender will likely be characterized not by universal consensus but by greater acceptance of diversity and self-determination.

Summary

At its core, this exploration of gender reveals that what many take as natural, universal truth is actually a complex social construction that varies dramatically across cultures and throughout history. The binary system dominant in Western societies represents just one possible organization of gender—neither inevitable nor universal—and often fails to capture the rich diversity of human experience. When we recognize gender as something we create collectively rather than something fixed in biology, we gain the freedom to imagine new possibilities that better serve human flourishing. The insights gained from understanding gender's complexity extend far beyond academic interest—they offer practical tools for creating more just and authentic lives. For parents, educators, and policymakers, this knowledge provides frameworks for supporting children in developing healthy relationships with gender, whether they conform to expectations or not. For individuals struggling with rigid gender norms, recognizing the constructed nature of these expectations can be profoundly liberating. And for society broadly, questioning gender assumptions opens pathways to addressing persistent inequalities and expanding human potential. What might your life look like if you could experience gender as a creative possibility rather than a restrictive requirement? How might our communities transform if we designed them around human needs rather than gender divisions? These questions invite us to participate in authoring gender's next chapter.

Best Quote

Review Summary

Strengths: The concept of a choose-your-own-adventure book focused on gender exploration is innovative and intriguing. Weaknesses: The execution of the book is criticized for inaccuracies and insufficient playtesting, which results in later entries negating earlier choices. The review highlights issues with the handling of nonbinary and intersex themes, pointing out contradictions and erasure of personal decisions. Overall Sentiment: Critical Key Takeaway: While the book's premise is promising, its flawed execution, particularly in terms of choice continuity and representation of gender themes, undermines its potential impact and reader experience.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.