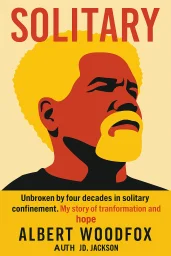

Solitary

Unbroken by Four Decades in Solitary Confinement. My Story of Transformation and Hope

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Memoir, Politics, Autobiography, Social Justice, Biography Memoir, African American, Race

Content Type

Book

Binding

Audiobook

Year

2019

Publisher

Audible Studios

Language

English

ASIN

B0F7YY6F75

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Solitary Plot Summary

Introduction

In the sweltering heat of Louisiana's Angola Prison, Albert Woodfox endured what would become the longest period of solitary confinement in American history—43 years and 10 months in a 6-by-9-foot cell. His crime, according to the state, was the 1972 murder of a prison guard, though evidence of his innocence would gradually mount over the decades. What makes Woodfox's story extraordinary is not just the unimaginable length of his isolation, but the remarkable inner strength he cultivated to survive it. Through political education, disciplined routine, and unwavering principles, he transformed his tiny cell from a space of punishment into a site of resistance and personal growth. Woodfox's journey illuminates the darkest corners of America's criminal justice system while simultaneously revealing the astonishing resilience of the human spirit. From his early life in the segregated streets of New Orleans to his political awakening through the Black Panther Party, and from his wrongful conviction to his eventual freedom at age 69, his story transcends a simple narrative of injustice. It offers profound insights into how systemic racism operates within the prison system, how solidarity can sustain people through seemingly unbearable circumstances, and how maintaining one's dignity and principles can become both a burden and a lifeline when everything else has been stripped away.

Chapter 1: Early Life and the Path to Angola

Albert Woodfox entered the world on February 19, 1947, in the segregated "Negro" wing of Charity Hospital in New Orleans. Born to a teenage mother, Ruby Edwards, who was barely seventeen, Woodfox's early years were marked by poverty and instability. His biological father abandoned the family before his birth, but his stepfather, James B. Mable, a Navy chef whom young Albert called "Daddy," provided a measure of stability during his early childhood. This relative security ended abruptly when Woodfox was eleven and his stepfather was forced to retire after 25 years of service. The family relocated to North Carolina, where his stepfather began drinking heavily and became physically abusive toward his mother. The pivotal moment in Woodfox's childhood came when his mother fled the abusive relationship, taking Albert and two siblings back to New Orleans while painfully leaving two other children behind temporarily. They settled in the Sixth Ward, also known as the Tremé, a poor Black neighborhood where Ruby created what Woodfox later described as "an oasis" inside their home despite the poverty that surrounded them. Unable to read or write but fiercely resourceful, his mother took whatever jobs she could find to support her children, sometimes including prostitution—a reality that young Albert struggled to understand and accept. By his teenage years, Woodfox had joined a neighborhood gang called the High Steppers and begun shoplifting food when necessary. His education suffered as street life became increasingly appealing, and by eighteen, he was arrested for car theft and sent to Angola prison for the first time. This began a cycle of incarceration and brief periods of freedom that defined his early adulthood. Each stint in prison further exposed him to the brutality of the criminal justice system while providing few opportunities for rehabilitation. Between prison terms, Woodfox's criminal activities escalated from theft to armed robbery, partly to support a heroin addiction he would later overcome. Growing up in the segregated South, Woodfox experienced the dehumanizing effects of Jim Crow laws firsthand. One particularly painful memory he carried throughout his life occurred during Mardi Gras when he was about twelve. Reaching for some beads to give his mother as a birthday gift, a young white girl grabbed them at the same time. When he explained they were meant for his mother, the girl ripped them apart while calling him a racial slur. "The pain I felt from that young white girl calling me nigger will be with me forever," he later recalled. Such experiences of racism, coupled with poverty and the criminal justice system's biases, shaped his worldview in profound ways. By 1969, Woodfox seemed destined for a life cycling through prisons. After being convicted of armed robbery, he escaped from a New Orleans courthouse during sentencing and fled to New York City. There, he was wrongfully accused of another robbery, severely beaten, and imprisoned in the Manhattan House of Detention, known as "the Tombs." It was in this harsh environment that Woodfox would encounter members of the Black Panther Party—an encounter that would transform his understanding of himself and society. As he later reflected, he had been living as a predator, but was about to discover a new purpose that would sustain him through unimaginable hardship.

Chapter 2: Political Awakening Through the Black Panthers

In April 1970, while imprisoned in New York's notorious Tombs, Woodfox met three men who would change the trajectory of his life—members of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Unlike other prisoners Woodfox had encountered, these men carried themselves with dignity and purpose. They showed respect to everyone, asking fellow prisoners their names and offering assistance rather than seeking to dominate through fear or violence. "When they talked to someone, they asked him his name," Woodfox recalled. "What do you need?" they asked. Within days, they had taken charge of the tier not through force but by sharing their food and treating everyone as equals. These Panthers introduced Woodfox to concepts that initially seemed abstract: economics, revolution, racism, and the oppression of poor people worldwide. Though skeptical at first, he continued attending their discussions, drawn by their discipline and camaraderie. His intellectual awakening accelerated when another prisoner gave him a book called "A Different Drummer" by William Melvin Kelley. The story of Tucker Caliban, a descendant of a powerful African who had been enslaved, resonated deeply with Woodfox. Like the protagonist who burned down his past to forge a new identity, Woodfox felt the desire to transform himself. "After reading A Different Drummer I started to believe, for the first time in my life, that one man could make a difference," he wrote. The Panthers' teachings began making sense to Woodfox as he recognized how institutionalized racism had shaped his own life. He saw how poverty had pushed him and other young men in his neighborhood toward crime. He reflected on his mother's struggles under Jim Crow laws and how he had judged her harshly for her inability to read. He even found compassion for the violent prisoners he'd encountered, understanding how they had been dehumanized by a racist system. The Panthers' principles—freedom, power to determine the destiny of the Black community, decent housing, education, justice, and peace—resonated with him intellectually and emotionally. "It was as if a light went on in a room inside me that I hadn't known existed," he wrote. When Woodfox returned to Angola in 1971, he was a changed man. He carried with him not just the principles of the Black Panther Party but a new moral framework. He began speaking to other prisoners about their rights and dignity. "In prison," he told them, "first they reduce your value as a human being, then they break your will." He urged them to reeducate themselves and work together rather than fighting among themselves. His message was simple but powerful: "You deserve better than what you're getting." This political consciousness gave him purpose beyond mere survival and would later sustain him through decades of solitary confinement. At Angola, Woodfox met Herman Wallace, another prisoner who had been transformed by the Panthers' teachings. Together, they formed the first official chapter of the Black Panther Party behind prison walls. Their work included organizing prisoners, pooling resources, and most notably, creating an "antirape squad" to protect new prisoners from sexual assault. Every Thursday, when new prisoners arrived, they would meet them, introduce themselves, and explain they were now under the protection of the Black Panther Party. This direct action against the prison's culture of sexual violence represented a profound moral stance and demonstrated the practical application of the Panthers' principles of community protection and solidarity.

Chapter 3: Framed for Murder: The Beginning of Solitary

On April 17, 1972, the course of Albert Woodfox's life changed forever when prison guard Brent Miller was stabbed to death in Pine 1 dormitory at Angola. Though Woodfox was nowhere near the scene of the crime, he quickly became a target of the investigation. When he reached the front of the line of prisoners being questioned about the murder, Hayden Dees, the head of security, immediately accused him: "Woodfox, you motherfucking nigger, you killed Brent Miller." Despite Woodfox's denial, he was handcuffed, shackled, and taken to solitary confinement, known as Closed Cell Restricted (CCR). This began what would become the longest period of solitary confinement in American penal history. The timing of Miller's murder coincided with significant tensions at Angola. The prison was under scrutiny from the Justice Department following a prisoner lawsuit alleging unconstitutional living conditions. Warden C. Murray Henderson was being pressured to integrate the prison and eliminate inmate guards, changes resisted by Dees and other longtime Angola staff from families who had run the prison for generations. Additionally, Woodfox and Wallace had been organizing prisoners around Black Panther Party principles, challenging the status quo of violence and exploitation that had long defined Angola. Within 24 hours of Miller's murder, Warden Henderson told reporters that "black militants" were responsible, despite Deputy Warden Lloyd Hoyle having previously stated there was "no explanation" for the incident. The evidence against Woodfox was flimsy at best. The state's star witness, Hezekiah Brown, was a serial rapist in his sixties who initially told investigators he was at the blood plasma unit during the murder. Only after being awakened at midnight and brought to a room with prison officials did he change his story to implicate Woodfox and the others. Two other witnesses, Joseph Richey (a prisoner Woodfox had previously prevented from raping a young inmate) and Paul Fobb (who was legally blind), gave contradictory testimonies. Meanwhile, a clear, identifiable bloody fingerprint found at the crime scene didn't match Woodfox or any of the other accused men. Woodfox's trial in 1973 was a travesty of justice. He was represented by an inexperienced lawyer working pro bono, facing prosecutors who were part of a tight-knit community determined to convict him. The all-white jury deliberated for less than an hour before finding him guilty, despite testimony from multiple witnesses who placed Woodfox elsewhere during the murder. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole. "I remember thinking they would not break me," Woodfox recalled of hearing the verdict. "I wouldn't let them break me, no matter what." This determination would sustain him through the decades of isolation that followed. After the trial, evidence emerged that the state's witnesses had received significant benefits for their testimony. Brown was moved to the most comfortable quarters at Angola, known as the "dog pen," and eventually had his life sentence commuted. Richey was given weekend furloughs and so much freedom that he went on to rob three banks while still technically in prison. Fobb received a medical furlough and spent years outside prison. Meanwhile, defense witnesses were punished—one was put in solitary confinement after testifying. Years later, documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act revealed that FBI informants had deliberately sabotaged Woodfox's defense committee, preventing funds from being raised for adequate legal representation.

Chapter 4: Surviving the Cell: Mental Discipline and Resistance

Solitary confinement at Angola's CCR was designed to break a prisoner's spirit. Locked in a 6-by-9-foot cell for 23 hours a day, Woodfox faced conditions that the United Nations would later classify as torture. The cell contained only a bare bunk attached to the wall, a ceramic toilet and sink, and a small metal table and bench. Meals were pushed under the cell door across the filthy floor. Whenever prisoners were taken off the tier, they were subjected to humiliating strip searches and full restraints. Rats came up through shower drains, mice appeared at night, and red ants periodically invaded cells, getting into clothes, sheets, mail, and food. Within this dehumanizing environment, Woodfox made a profound decision: he would not be broken. "If there is one word to describe the next years of my life it would be 'defiance,'" he wrote. When guards made racist comments, Woodfox talked back. When they threatened other prisoners, he shook the bars and yelled. He knew the consequences would be severe—four or five guards would enter his cell and beat him—but his moral principles wouldn't let him back down. "I was always scared shitless," he admitted. "Sometimes my knees would shake and almost buckle. I forced myself to learn how not to give in to fear." This courage in the face of certain punishment became a cornerstone of his resistance. To maintain his sanity, Woodfox established a rigorous daily routine. He exercised in his cell every morning, doing push-ups, sit-ups, and other calisthenics despite the limited space. He read for at least two hours daily, educating himself through books on philosophy, history, politics, and science. He kept his cell meticulously clean, scrubbing every surface daily. This structured approach to his days gave him a sense of control in an environment designed to strip all autonomy. "I made a conscious decision not to let my personality be shaped by my environment," he explained. This mental discipline allowed him to transform his cell from a space of punishment into what he called "a university, a hall of debate, a law school." One of Woodfox's most significant acts of resistance came through his refusal to submit to unnecessary strip searches. In 1977, after years of enduring this humiliation, Woodfox connected the practice to how enslaved African Americans were treated—forced to strip down on auction blocks while their bodies were inspected like livestock. He, along with Wallace and fellow Panther Robert King (who had also been wrongfully convicted of a prison murder), organized a petition against the practice, gathering signatures from nearly everyone in CCR. When prison officials ignored their petition, Woodfox physically resisted the next strip search, enduring beatings and additional punishment for his defiance. Eventually, with the help of New Orleans Legal Assistance, they won a lawsuit limiting when and how strip searches could be conducted. Perhaps most remarkably, Woodfox maintained his commitment to helping others despite his own extreme circumstances. He taught illiterate prisoners to read through the bars of his cell, spent his limited resources to help those without family support, and intervened when he saw guards abusing mentally ill prisoners. His proudest achievement during his time in solitary was teaching a fellow prisoner named Charles "Goldy" to read. Using a dictionary and the sound key at the bottom of each page, Woodfox patiently worked with Goldy during their hours out of their cells. "Anytime you can't get a word, holler, Goldy, no matter what time," he told him. "Day or night if you have a question, just ask me." Within a year, Goldy was reading at a high school level. "The world was now open to him," Woodfox wrote.

Chapter 5: The Angola Three: Brotherhood in Isolation

The bond between Albert Woodfox, Herman Wallace, and Robert King—collectively known as the "Angola Three"—transcended ordinary friendship. Despite being held in separate cells and often in different buildings, they maintained a connection that became essential to their survival. They shared not only the experience of wrongful conviction and extreme isolation but also a commitment to the principles of the Black Panther Party that gave meaning to their suffering. "Our resistance gave us an identity," Woodfox wrote. "Our identity gave us strength. Our strength gave us an unbreakable will." This mutual support system proved crucial as the years in solitary stretched into decades. Communication between the three men required extraordinary creativity and persistence. When housed on different tiers, they passed notes through sympathetic orderlies or by creating elaborate systems using other prisoners as intermediaries. Sometimes they would intentionally get themselves sent to the dungeon—a punishment area with even harsher conditions—just to have an opportunity to speak face-to-face. During these rare moments together, they debated political ideas, discussed books they had read, and strategized about improving conditions for all prisoners. "We had many conversations and debates in the dungeon," Woodfox recalled, highlighting how they transformed even punishment into an opportunity for intellectual growth and solidarity. The Angola Three organized their respective tiers through a system of collective decision-making that reflected their political principles. They held meetings during their hour out of their cells, asking men what kind of tier they wanted and what conduct they expected from one another. Based on these discussions, they created rules that everyone agreed to follow. When prisoners with regular visitors received money in their accounts, Woodfox, Wallace, and King asked them to pool these resources for the benefit of everyone. Each week, every prisoner on the tier could request one item from the commissary—candy, shower slippers, underwear, tobacco—paid for from this common fund. This simple act of sharing transformed the atmosphere on the tiers, reducing theft and fostering mutual respect. Education became central to their community-building efforts. They organized martial arts practice, reading sessions, math classes, and spelling tests. They encouraged debates and conversations, telling each man he had a voice. "Stand up for yourself," they urged, "for your own self-esteem, for your own dignity." This approach resonated even with the most hardened prisoners. As Woodfox observed, "Even the roughest, most hardened person usually responds when you see the dignity and humanity in him and ask him to see it for himself." Through these efforts, they created what prison officials feared most: a community of prisoners who recognized their shared humanity and stood together against dehumanization. Their solidarity extended to collective action when conditions became intolerable. They organized tier-wide protests that included refusing to return to cells when their hour was up, refusing to hand back food trays after meals, shaking cell doors ("shaking down"), or banging on tables or sinks with shoes ("knocking down"). Before any action, they sought consensus, knowing retaliation would follow. Sometimes officials responded with tear gas or by turning the entire tier into a dungeon, emptying cells and throwing all possessions into a pile. After such collective punishments, prisoners would help each other recover, asking "Whose is this?" and walking items down to their rightful owners—a powerful demonstration of community in the face of attempts to break their unity.

Chapter 6: Legal Battles: The Long Road to Justice

The path to freedom for Albert Woodfox was paved with countless legal filings, courtroom appearances, and hard-fought battles against a system determined to keep him confined. From his cell, Woodfox transformed himself into a skilled jailhouse lawyer, mastering complex legal terminology and procedures through sheer determination. "If I came across a passage I didn't understand in the law books, I read it over and over again," he explained. "I'd read a single passage 40 or 50 times until I was somehow able to absorb the meaning." This self-education became essential as he navigated the labyrinthine appeals process that would eventually lead to his freedom. For nearly 25 years, Woodfox and Wallace languished in solitary confinement, virtually forgotten by the outside world. The Black Panther Party that had once supported them no longer existed, and their letters to legal organizations went unanswered. This changed dramatically in 1997 when a young law student named Scott Fleming read a letter from Wallace describing their situation. Moved by their plight, Fleming began investigating their case and reached out to former Black Panther Malik Rahim, who was shocked to learn his old comrades were still imprisoned. This connection marked the beginning of a support network that would eventually bring international attention to their case. A breakthrough came in 2008 when Federal Judge James Brady overturned Woodfox's conviction, citing racial discrimination in the selection of his grand jury foreperson and ineffective assistance of counsel. However, the state of Louisiana appealed this decision, and Woodfox remained in solitary confinement while the legal process dragged on. Louisiana Attorney General Buddy Caldwell launched a public campaign against Woodfox's release, falsely characterizing him as "the most dangerous man in America" and a "serial rapist." These unsubstantiated claims, along with pressure on potential hosts for Woodfox's house arrest, resulted in the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversing Judge Brady's bail order. The legal team expanded as renowned civil rights attorney George Kendall and his colleagues took on both the men's criminal appeals and a civil lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of their decades in solitary confinement. This dual legal strategy—fighting both for exoneration and for humane conditions—created multiple avenues for progress. The civil suit resulted in a landmark ruling by U.S. Magistrate Judge Docia Dalby, who found that being locked down for three decades could constitute cruel and unusual punishment, writing that "with each passing day its effects are exponentially increased, just as surely as a single drop of water repeated endlessly will eventually bore through the hardest of stones." As awareness grew, so did political pressure. U.S. Representative John Conyers, chair of the House Judiciary Committee, visited Woodfox and Wallace at Angola and called for a Department of Justice investigation into their case. Amnesty International declared their confinement a human rights violation. Perhaps most surprisingly, Brent Miller's widow, Teenie Rogers, came forward to support them after learning about the suppressed evidence in the case, writing to the governor that "the state of Louisiana seems willing to live with" the tragedy of keeping innocent men in solitary confinement. "I am not," she declared. This growing coalition of supporters brought increasing pressure on Louisiana officials, who responded with increasingly desperate measures to maintain Woodfox's conviction.

Chapter 7: Freedom and Legacy: Life After Confinement

On February 19, 2016—his 69th birthday—Albert Woodfox walked out of the West Feliciana Parish jail a free man. After 43 years and 10 months in solitary confinement, after multiple trials and appeals, after countless legal setbacks and personal losses, his ordeal had finally ended. The path to this moment had been neither straight nor certain. Facing a third trial with the same procedural disadvantages that had characterized his previous convictions, Woodfox made the difficult decision to accept a plea deal. The plea was "no contest" (nolo contendere) to manslaughter and burglary charges—a compromise that allowed him to maintain his innocence while acknowledging that the state had enough evidence to potentially convict him again. Woodfox's first actions as a free man revealed much about his character and priorities. His brother drove him directly to the cemetery where their mother Ruby was buried. Unable to attend her funeral twenty-two years earlier, Woodfox could finally pay his respects. He also visited the graves of his sister Violetta and his childhood friend Michael Augustine. The following day, he and his supporters bought "almost every flower" at a local Walmart and took them to Herman Wallace's grave. These pilgrimages to lost loved ones underscored how much had been taken from him beyond just his freedom—decades of family connections, shared experiences, and ordinary human joys that could never be restored. Adjusting to life outside prison presented numerous challenges. Woodfox had to learn to use modern technology, navigate social interactions, and manage the sensory overload of the outside world. Physical habits formed in confinement—like sleeping only a few hours at a time or becoming anxious in enclosed spaces—persisted. Yet he approached these challenges with the same methodical determination that had sustained him in solitary, gradually building a new life while maintaining the discipline and principles that had preserved his humanity through decades of isolation. He developed relationships with his daughter and great-grandchildren, building connections that prison had denied him for most of his life. Despite these difficulties, Woodfox embraced his role as a living witness to the injustices of solitary confinement and the broader failings of the American criminal justice system. He began speaking at universities, law schools, and human rights conferences, sharing his experiences and advocating for prison reform. He traveled to Yosemite National Park, fulfilling a dream born decades earlier while watching a National Geographic special in his cell. With Robert King, the third member of the Angola 3 who had been released in 2001, he called for the abolition of solitary confinement as a practice. Their advocacy contributed to growing national awareness about this issue, with several states implementing reforms to limit the use of solitary confinement in the years following Woodfox's release. In 2019, Woodfox published his memoir, which won the National Book Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. The book detailed not only the injustices he had endured but also the remarkable inner journey that allowed him to maintain his humanity in conditions designed to strip it away. He described how the political consciousness he developed through the Black Panther Party gave him the framework to understand his situation not as personal misfortune but as part of systemic injustice. This perspective allowed him to transform his suffering into resistance and to find meaning in standing up for principles larger than himself. "I view my experience as a testament to the human spirit," he wrote, "and to the power of solidarity."

Summary

Albert Woodfox's extraordinary journey from the streets of New Orleans to four decades in solitary confinement reveals the profound resilience of the human spirit in the face of systematic dehumanization. His transformation from a young man engaged in street crime to a disciplined political thinker who educated fellow prisoners, organized resistance against abusive conditions, and maintained his dignity through unimaginable hardship demonstrates how even the most oppressive circumstances cannot crush the human capacity for growth and compassion. Throughout his ordeal, Woodfox refused to allow his keepers to define him, instead drawing strength from his political principles and the unbreakable bond with his comrades Herman Wallace and Robert King. The legacy of Woodfox's struggle extends far beyond his individual case, illuminating the broader injustices of America's prison system and the particular cruelty of solitary confinement. His story challenges us to confront uncomfortable truths about how racism, political repression, and institutional corruption can pervert the justice system. Yet it also offers hope by showing how persistent legal advocacy, international solidarity, and the moral clarity of those fighting for justice can eventually overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles. For anyone seeking to understand the human cost of mass incarceration or the power of principled resistance against oppression, Woodfox's journey provides both a sobering education and an inspiring testament to the endurance of dignity and the possibility of transformation even in the darkest circumstances.

Best Quote

“In my forties, I chose to take my pain and turn it into compassion, and not hate. Whenever I experienced pain of any origin I always made a promise to myself never to do anything that would cause someone else to suffer the pain I was feeling in that moment. I still had moments of bitterness and anger. But by then I had the wisdom to know that bitterness and anger are destructive. I was dedicated to building things, not tearing them down.” ― Albert Woodfox, Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades in Solitary Confinement

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights the book's ability to provide a gruelling yet rewarding narrative, emphasizing Woodfox's transformation and the influence of the Black Panthers' teachings on his philosophy. The book is noted for its insightful depiction of the harsh realities of prison life and systemic racism.\nOverall Sentiment: The review conveys a generally positive sentiment, appreciating the depth and impact of Woodfox's story despite its challenging content.\nKey Takeaway: "Solitary" is a powerful memoir that explores Albert Woodfox's journey through the brutal realities of prison life and systemic racism, underscored by his adoption of Black Panther principles, which provided him with strength and purpose amidst adversity.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.