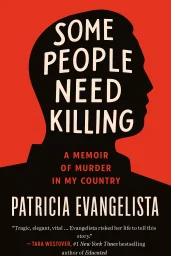

Some People Need Killing

A Memoir of Murder in My Country

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Memoir, Politics, Audiobook, True Crime, Asia, Journalism, Crime

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2023

Publisher

Random House

Language

English

ASIN

0593133137

ISBN

0593133137

ISBN13

9780593133132

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Some People Need Killing Plot Summary

Introduction

In the early hours of July 1, 2016, residents of a Manila slum awoke to the sound of gunshots. By dawn, three bodies lay in the narrow alleyways, each with a cardboard sign: "Drug pusher, do not emulate." This scene would repeat thousands of times across the Philippines in the years that followed, marking the beginning of one of the most brutal anti-drug campaigns in modern history. The newly inaugurated President Rodrigo Duterte had made good on his campaign promise to wage a war on drugs, unleashing a wave of violence that would transform the nation and challenge fundamental notions of justice, human rights, and democratic governance. This bloody crusade offers a chilling case study in how populist authoritarianism can weaponize legitimate public concerns to justify systematic human rights abuses. Through examining Duterte's rise to power, his rhetoric of fear, and the mechanics of state-sanctioned violence, we gain insight into how quickly democratic norms can erode when fear overrides rights protections. Yet the story also reveals remarkable courage among survivors, journalists, and human rights defenders who risked everything to document abuses and preserve truth against official denials. For anyone concerned with the fragility of democratic institutions, the power of populist messaging, or the human cost of security-first policies, this examination of the Philippines' descent into violence offers urgent lessons about the dangers of sacrificing human rights in the name of public safety.

Chapter 1: Davao's Deadly Laboratory: Duterte's Rise to Power (1988-2016)

Rodrigo Duterte's political journey began far from the presidential palace in Manila. In 1988, he became mayor of Davao City, a sprawling urban center on the southern island of Mindanao known for its lawlessness and violence. At the time, Davao was plagued by communist insurgents, criminal gangs, and a reputation as the "murder capital" of the Philippines. This environment provided the perfect laboratory for Duterte to develop his controversial approach to governance—one that would later be exported to the entire nation. Over his two decades as mayor, Duterte transformed Davao through methods that blended populist appeal with authoritarian tactics. He cultivated an image as a man of the people, living simply and speaking the crude language of the streets rather than the polished rhetoric of traditional politicians. Yet beneath this folksy exterior lay a ruthless approach to crime. During his tenure, human rights organizations documented the emergence of the "Davao Death Squad," a vigilante group allegedly linked to city officials that targeted suspected criminals, particularly drug dealers and users. Between 1998 and 2015, over 1,400 extrajudicial killings were recorded in Davao City. Duterte's relationship with these killings became a defining aspect of his political persona. While never explicitly admitting to ordering extrajudicial executions, he frequently made statements that appeared to endorse them. "In Davao, I do not allow people to use drugs," he once declared in a television interview. "I will really kill you." This strategic ambiguity allowed him to signal his methods to supporters while maintaining plausible deniability. When human rights organizations or the Commission on Human Rights attempted to investigate the Davao Death Squad, they faced obstruction and ridicule from local authorities. The "Davao model" gained national attention because it responded to real public anxieties about crime and ineffective governance. Traditional politicians had failed to address these concerns through conventional means, creating an opening for Duterte's alternative approach. Visitors to Davao, including business leaders and politicians, returned with stories of a clean, orderly city where people felt safe walking at night. The economic growth that accompanied this security—with new investments flowing into the once-dangerous city—seemed to validate Duterte's methods regardless of human rights concerns. By 2015, Davao had become a pilgrimage site for those seeking to understand its transformation, with the darker aspects of this change often overlooked. Media coverage played a crucial role in constructing the myth of Davao. Local journalists who attempted to investigate the death squad faced intimidation and threats. National media often focused on Duterte's colorful personality and unconventional style rather than critically examining the human costs of his approach. This created an information environment where many Filipinos were aware of allegations against Duterte but did not fully confront their implications. The narrative of a chaotic city tamed through strong leadership proved more compelling than concerns about due process or human rights. By the time Duterte considered a presidential run, the Davao experiment had provided him with both a governance template and a powerful campaign narrative. He could point to concrete results—a safer city, economic growth, and efficient services—while dismissing human rights concerns as the complaints of elites disconnected from ordinary people's security fears. The laboratory of Davao had produced a model that would soon be implemented nationwide, with consequences far more devastating than most Filipinos could have imagined.

Chapter 2: Campaign of Fear: Rhetoric and Election Victory (2016)

The 2016 presidential campaign revealed Duterte's masterful use of fear as a political weapon. While his opponents focused on traditional issues like economic policy and anti-corruption measures, Duterte centered his campaign on a single, emotionally charged message: the Philippines was being destroyed by drugs, and only he had the courage to address this existential threat. "If I become president, I will order the police to find those people involved in drugs and kill them," he declared at campaign rallies. "The funeral parlors will be packed." Rather than damaging his prospects, this shocking rhetoric distinguished him from conventional politicians perceived as ineffective. Duterte's campaign strategy involved painting an apocalyptic picture of a nation on the brink of becoming a "narco-state." He claimed that 3-4 million Filipinos were drug addicts, later inflating this number to 7-8 million—figures that dramatically exaggerated the actual scale of drug use according to official surveys. By amplifying these fears and positioning himself as the only candidate willing to take drastic action, Duterte created a sense of urgency that overwhelmed concerns about his methods. His promise of results within three to six months appealed to voters tired of incremental change and complex policy solutions that never seemed to improve their daily lives. The campaign masterfully exploited social media to bypass traditional gatekeepers and speak directly to voters. Duterte's supporters established a network of Facebook pages and Twitter accounts that amplified his messages and attacked his critics. These platforms became echo chambers where followers could reinforce their support while insulating themselves from opposing viewpoints. When human rights advocates or journalists raised concerns about his death squad history or violent rhetoric, they were dismissed as elitists out of touch with ordinary Filipinos' concerns. This polarization strategy effectively neutralized criticism by framing it as evidence of establishment bias rather than legitimate concern. Duterte's path to the presidency began with reluctance—or at least the appearance of it. For months in 2015, he publicly wavered about whether to run, creating an atmosphere of anticipation that heightened public interest. "Run, Duterte, Run" movements sprang up across the country, with supporters organizing rallies even without an official campaign. By positioning himself as a reluctant candidate who would only run if the people demanded it, Duterte cultivated an image as a servant responding to a call rather than a politician seeking power. This narrative of reluctant leadership added to his authenticity in contrast to career politicians. Unlike his main opponents—Mar Roxas, the administration candidate with an economics degree from Wharton; Grace Poe, the adopted daughter of a beloved movie star; and Jejomar Binay, the incumbent vice president—Duterte presented himself as an ordinary Filipino, unpolished and authentic. He spoke in crude language peppered with profanity and jokes about sex. He made no attempt to hide his controversial views or conform to expected standards of presidential behavior. This deliberate rejection of political norms became a central feature of his appeal, signaling to voters that he represented a genuine break from the established order they had grown to distrust. By election day in May 2016, Duterte had successfully positioned himself as the voice of frustrated Filipinos demanding change. He won with 39 percent of the vote in a five-way race, securing 16 million votes—a clear mandate but far from a majority of the electorate. His victory represented a profound rejection of the political establishment and traditional democratic norms. Voters had knowingly elected a candidate who openly advocated extrajudicial killings and threatened to bypass constitutional constraints. The campaign had normalized extreme rhetoric and solutions, setting the stage for a presidency that would test the resilience of Philippine democratic institutions and the international community's response to democratic backsliding in the name of popular mandate.

Chapter 3: Institutionalizing Violence: Police Operations and Death Squads

President Duterte wasted no time fulfilling his campaign promise. Within hours of his inauguration on June 30, 2016, the first casualties of his war on drugs were reported. The body of an unidentified man was found in a Manila alley with a cardboard sign declaring him a "Chinese drug lord." This would become a familiar scene in the weeks and months that followed. The Philippine National Police, under the leadership of Duterte loyalist Ronald "Bato" dela Rosa, launched "Operation Double Barrel," a nationwide anti-drug campaign with two components: high-value targets (drug lords and financiers) and street-level dealers and users. The latter effort, called "Oplan Tokhang" (from Visayan words meaning "knock and plead"), became the most visible and deadly aspect of the drug war. The mechanics of the drug war revealed its true nature as a campaign of terror rather than law enforcement. Police officers, sometimes accompanied by local officials, would visit the homes of suspected drug users and dealers, whose names appeared on "watch lists" compiled by local authorities. These individuals would be asked to surrender, admit their involvement with drugs, and pledge to reform. Millions did so, often out of fear rather than guilt. Those who resisted or later returned to drug use became targets for what police euphemistically called "legitimate police operations." These operations frequently ended with suspects dead, their bodies displayed in public as warnings. Police reports almost invariably claimed that the deceased had "fought back" (nanlaban in Filipino), justifying the use of lethal force. Alongside police operations, a wave of vigilante killings swept through urban poor communities. Masked gunmen on motorcycles would execute suspected drug users and dealers, often leaving behind cardboard signs labeling the victims as drug pushers. While the government denied directing these killings, Duterte's rhetoric effectively encouraged them. "Do it yourself if you have guns," he told the public in one speech. These vigilante-style killings created a climate of terror in affected communities while allowing the government to maintain plausible deniability. The distinction between police operations and vigilante killings became increasingly blurred, with evidence suggesting that off-duty police officers or police assets were involved in many supposedly vigilante attacks. The institutionalization of violence was reinforced through language and bureaucratic procedures. Police reports referred to those killed not as victims but as "neutralized drug personalities." Deaths were classified as "deaths under investigation" rather than homicides or murders. Media outlets, initially publishing front-page photos of bloodied bodies, gradually reduced their coverage as the killings became too numerous and routine to merit individual attention. This semantic and procedural framework helped distance authorities from accountability while desensitizing the public to the mounting death toll. Within police ranks, the drug war created a system of perverse incentives. Officers faced pressure to produce results in the form of arrests and "neutralizations," with some reports suggesting informal quotas. Whistleblowers later revealed that some officers received cash rewards for kills, creating a bounty system that encouraged abuse. The president's repeated promises to pardon officers who killed in the line of duty further removed normal constraints on the use of deadly force. This institutional corruption extended to evidence planting, with numerous testimonies describing how police would place guns in dead suspects' hands or scatter small packets of drugs near bodies to justify killings. By 2018, the violence had become normalized. What began as shocking headlines became routine reports buried in the back pages of newspapers. The institutionalization was complete—extrajudicial killings had transformed from extraordinary events to standard government procedure, with the machinery of state power fully aligned behind a policy of lethal force against its own citizens. This normalization represented perhaps the most insidious aspect of the campaign—not just the thousands of deaths, but the way in which extrajudicial killing had been transformed from an outrage into an expected feature of Philippine governance.

Chapter 4: Human Cost: Communities Shattered by State Terror

Behind the statistics of Duterte's drug war lay thousands of individual tragedies—lives cut short, families shattered, and communities traumatized. In the urban slums of Manila, Caloocan, and other cities, residents would awaken to the sound of gunshots, only to find neighbors lying dead in alleyways or inside their modest homes. The victims came from all walks of life but shared common vulnerabilities: poverty, lack of legal resources, and often a history of substance use or petty crime. Jhay-ar Dilangalen was a 23-year-old tricycle driver killed during a police raid; witnesses said he was unarmed and begging for his life when officers shot him. Kian delos Santos was a 17-year-old student dragged into an alley by plainclothes police and executed; CCTV footage contradicted the official claim that he had fought back. These stories, multiplied thousands of times across the country, revealed the human cost of Duterte's war. The drug war's impact fell disproportionately on the urban poor. While Duterte had promised to target drug lords and corrupt officials, the vast majority of victims were small-time users and dealers from impoverished communities. Wealthy drug suspects were more likely to be arrested and given due process than summarily executed. This class disparity revealed the drug war's function as a form of social control rather than genuine narcotics enforcement. Poor communities, already marginalized and lacking political power, became hunting grounds where residents lived in constant fear. Families of victims faced not only the trauma of losing loved ones but also social stigma, as the drug war successfully branded all victims as criminals deserving of their fate. For surviving family members, the nightmare continued long after the killings. Many faced immediate practical challenges: funeral expenses they couldn't afford, loss of household income, and children suddenly orphaned. Beyond these material hardships came psychological trauma and social stigma. Communities often shunned the families of drug war victims, fearing association with them might make them targets as well. Children of those killed suffered particularly severe impacts, with studies documenting symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and behavioral problems. Some dropped out of school due to bullying or financial constraints. Others were forced to assume adult responsibilities, caring for younger siblings or working to support their families. These cascading effects extended the drug war's damage across generations. Women bore a disproportionate burden in the aftermath of killings. When husbands or sons were killed, mothers, wives, and sisters were left to navigate the financial and emotional aftermath. They became the primary advocates for justice, filing police reports, speaking to media, and joining support groups for families of victims. This activism often came at great personal risk, as authorities intimidated those who questioned the official narratives around killings. Nanette Castillo, whose son was killed by unidentified gunmen, described receiving death threats after she spoke publicly about her son's case. "They tell me I could be next," she told human rights investigators, "but I have nothing left to lose." Despite these threats, women-led organizations like Rise Up for Life and Rights emerged as crucial voices documenting abuses and demanding accountability. In communities caught in the drug war's crosshairs, daily life was transformed by fear and suspicion. Residents described changing their routines to avoid being outside after dark, when most killings occurred. They grew wary of unfamiliar motorcycles or vans that might carry death squads. Local government officials, who often helped compile the "watch lists" that became virtual death warrants, wielded unprecedented power over residents. Community bonds frayed as neighbors feared being associated with suspected drug users or informing on others to protect themselves. The social fabric of already vulnerable communities was further damaged by this climate of terror, creating conditions where residents became even more dependent on local power structures for protection and increasingly unable to assert their rights against abuses. Perhaps most insidious was the normalization of violence. Children incorporated drug war terminology into play, acting out "Tokhang" operations with toy guns. Neighbors stopped reporting killings, accepting them as inevitable. Even victims' families sometimes adopted the rhetoric of deserved punishment, stating that relatives "must have done something wrong" to avoid being targeted themselves. This internalization of state violence represented its ultimate success—when citizens begin policing themselves and each other according to the logic of authoritarian control, the system perpetuates itself even without constant enforcement.

Chapter 5: Resistance and Accountability: Survivors Fight for Justice

Despite overwhelming odds, resistance to the drug war emerged through various forms of courage and memory-keeping. Families of victims, particularly mothers, became the frontline defenders of truth against official narratives that dehumanized their loved ones. Women like Normita Lopez, whose epileptic son Djastin was killed by police who claimed he was a drug dealer, transformed their grief into activism. Despite threats and poverty, these mothers attended court hearings, spoke at protests, and insisted their children be remembered as human beings, not statistics. Their personal testimonies challenged the government's attempt to reduce victims to mere criminals deserving of their fate. Documentation became a critical form of resistance. Journalists risked their safety to photograph crime scenes and interview witnesses when police controlled access. Photojournalist Raffy Lerma's iconic image of Jennelyn Olaires cradling her partner Michael Siaron's body—dubbed "La Pietà" for its resemblance to Michelangelo's sculpture—became a symbol of the drug war's human cost. These visual testimonies contradicted official claims that victims were dangerous criminals who "fought back," preserving evidence for future accountability. When Duterte dismissed this particular photograph as "melodramatic," it only highlighted the administration's fear of humanizing narratives that might generate public sympathy for victims. Legal challenges represented another front of resistance. Human rights lawyers from organizations like the Center for International Law filed petitions for writs of amparo (protection orders) for threatened communities and represented survivors like Efren Morillo, who survived a police shooting that killed four others. These cases rarely resulted in convictions but created official records of abuses and occasionally forced procedural reforms in police operations. The Supreme Court eventually ordered the release of police documents related to drug war killings, though compliance remained limited. These legal efforts, while often frustrated by a justice system reluctant to challenge executive power, established crucial precedents and preserved evidence for future accountability. Religious institutions, particularly the Catholic Church, provided crucial spaces for resistance. Catholic priests like Flaviano Villanueva established support programs for widows and orphans, while offering funeral services when families couldn't afford them. Churches maintained memorial walls listing victims' names, refusing to let them disappear into anonymity. When families feared claiming bodies from police, church workers ensured proper burials and documented identities for future investigations. This moral witness by religious leaders challenged the government's attempt to frame the drug war as necessary for social cleansing and offered an alternative ethical framework based on human dignity. International solidarity strengthened local resistance. Filipino diaspora communities organized protests at embassies worldwide. Human rights organizations documented cases for submission to the United Nations and International Criminal Court. Foreign journalists covered stories when local media faced intimidation. This international attention provided some protection for domestic activists and kept pressure on the Duterte administration despite its attempts to dismiss foreign criticism as colonial interference. The International Criminal Court's decision to open a preliminary examination in 2018, followed by a full investigation in 2021, gave survivors hope that accountability might eventually be achieved even if domestic institutions failed them. The most powerful form of resistance came through storytelling. Survivors who had witnessed killings or narrowly escaped death themselves risked their safety to share their experiences. Efren Morillo, who survived a police shooting that killed four of his friends, not only testified but became a complainant in a Supreme Court case challenging the drug war's implementation. These firsthand accounts, amplified through media and human rights reports, preserved the truth against official denials and created historical records that would outlast the Duterte administration itself. By refusing to be silenced, survivors ensured that the drug war's history could not be entirely rewritten by those in power.

Chapter 6: International Response: Global Reactions to Systematic Killings

The international community's response to the Philippine drug war revealed both the potential and limitations of global human rights mechanisms in the face of popular authoritarianism. Initial reactions were swift but inconsistent. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the International Narcotics Control Board issued early statements condemning extrajudicial killings, while human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch published detailed reports documenting patterns of abuse. These interventions, however, had limited immediate impact on Duterte's policies, which continued to enjoy strong domestic support. Western democratic governments displayed a notable ambivalence. The Obama administration expressed concern about human rights violations, prompting Duterte to respond with profane insults and threats to pivot toward China and Russia. When Donald Trump took office in 2017, the tone shifted dramatically. Trump reportedly praised Duterte's drug war in a phone call, saying he was doing an "unbelievable job." This inconsistency from the world's most powerful democracy undermined coordinated pressure and allowed Duterte to play major powers against each other. The European Union took a stronger stance, making human rights conditions for trade preferences and development assistance. When the EU Parliament passed resolutions condemning extrajudicial killings, Duterte rejected millions in aid rather than accept conditions. Duterte skillfully exploited international criticism to bolster domestic support. When criticized by foreign leaders or institutions, he responded with theatrical defiance, cursing foreign leaders and threatening to withdraw from international organizations. These performances resonated with many Filipinos who harbored resentment over the country's colonial history and perceived Western hypocrisy. Duterte reframed human rights criticism as neocolonial meddling, positioning himself as a defender of Philippine independence against foreign interference. This nationalist framing proved effective in neutralizing international pressure, as even Filipinos uncomfortable with the killings often rallied behind their president when he was criticized by outsiders. Asian neighbors largely adhered to principles of non-interference. Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN countries maintained economic and security relationships without public criticism of the drug war. China, seeing an opportunity to expand influence, offered support for Duterte's anti-drug campaign, including funding for rehabilitation centers. This regional acceptance provided Duterte with alternative partnerships that reduced the impact of Western pressure. The geopolitical competition in Southeast Asia thus created space for Duterte to continue his policies while playing major powers against each other for economic and strategic benefits. The International Criminal Court represented the most significant international accountability mechanism engaged. After a preliminary examination begun in 2018, ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda announced in 2021 that there was reasonable basis to believe crimes against humanity had been committed in the Philippines. Though Duterte had withdrawn the Philippines from the ICC in 2019, the court determined it retained jurisdiction over crimes committed while the country was a member. This development created the possibility of international prosecution, though practical challenges remained enormous given the government's refusal to cooperate with investigators. Media coverage and cultural responses formed another dimension of international engagement. Foreign journalists produced powerful investigations that reached global audiences, while documentaries like "On the President's Orders" and "A Thousand Cuts" received international acclaim. Filipino diaspora communities organized protests and advocacy campaigns in major cities worldwide. These efforts kept international attention focused on the Philippines when domestic coverage declined, creating pressure through public opinion even when official channels proved ineffective. The persistence of this attention prevented the drug war from fading entirely from global consciousness despite the administration's efforts to normalize it.

Chapter 7: Legacy of Impunity: Democratic Erosion and Lasting Trauma

As Duterte's term ended in 2022, the full impact of his drug war remained difficult to quantify. Official government figures acknowledged over 6,000 deaths in police operations, while human rights organizations estimated the total death toll, including vigilante killings, at between 12,000 and 30,000. Beyond these numbers lay deeper questions about the drug war's effectiveness, its impact on Philippine institutions, and its implications for the country's democratic future. By the administration's own metrics, the campaign failed to achieve its primary objective. Despite the thousands of deaths and arrests, drug availability and use remained widespread. The price of methamphetamine actually decreased in some areas, suggesting supply had not been significantly disrupted. The drug war's most lasting damage may be institutional. The Philippine National Police, already struggling with corruption allegations before 2016, became further compromised as accountability mechanisms were dismantled and officers received implicit permission to use deadly force with minimal oversight. The justice system buckled under the weight of drug cases, with courts and jails overwhelmed. Perhaps most concerning was the normalization of extrajudicial solutions to social problems, establishing a precedent that could extend beyond drug enforcement to other areas of governance. This erosion of institutional integrity will take years, if not decades, to repair. For Philippine democracy, the drug war represented a significant regression in human rights protections and due process. The campaign demonstrated how quickly constitutional safeguards could be circumvented through a combination of populist rhetoric, institutional pressure, and public fear. Civil society organizations that attempted to monitor abuses faced harassment and delegitimization. Media outlets reporting critically on the drug war encountered regulatory obstacles and online attacks. These patterns weakened the checks and balances essential to democratic governance, creating a template for future authoritarian measures justified in the name of public safety or national security. The psychological impact on Philippine society may prove even more enduring than the institutional damage. Communities targeted by the drug war experienced collective trauma that altered social relationships and trust in government. Children who witnessed killings or lost parents carry psychological wounds that will shape their development and worldview. Studies documented increased rates of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress among residents of heavily targeted areas. This psychological toll extends beyond direct victims to include witnesses, neighbors, and even those who supported the campaign but later came to question its methods or outcomes. Internationally, the drug war transformed the Philippines' image and relationships. Once celebrated for its 1986 People Power Revolution and democratic transition, the country became associated with human rights abuses and authoritarian tendencies. Traditional allies like the United States and European Union countries maintained economic and security relationships but grew increasingly critical of governance issues. Meanwhile, the administration's pivot toward China and Russia reflected a broader realignment away from Western liberal democratic norms toward more authoritarian models of development. This geopolitical shift may outlast Duterte's presidency, permanently altering the Philippines' international positioning. Perhaps the most troubling legacy is the culture of impunity that the drug war both reflected and reinforced. By the end of Duterte's term, the systematic killing of citizens by state forces had been normalized to a degree unimaginable before 2016. This normalization was evident in the 2022 election, when Ferdinand Marcos Jr. (son of the former dictator) won the presidency while promising to continue aspects of Duterte's drug war, albeit with less emphasis on killings. The ease with which Philippine society accepted extraordinary violence against certain categories of citizens suggests a profound weakening of human rights norms that may enable future abuses against other marginalized groups. Reversing this acceptance of impunity represents perhaps the greatest challenge for those seeking to restore democratic values and the rule of law in post-Duterte Philippines.

Summary

The Philippine drug war under President Rodrigo Duterte represents one of the most dramatic examples of how populist governance can rapidly transform a democratic society. What began as a campaign promise to eliminate drugs and crime within six months evolved into a systematic assault on human rights that claimed thousands of lives while eroding democratic institutions. The campaign's success depended on multiple reinforcing factors: a charismatic leader willing to openly advocate violence; a police force incentivized to produce bodies rather than justice; a propaganda machine that dehumanized targets and glorified killing; a judicial system too weak or compromised to provide accountability; and a population sufficiently frustrated with the status quo to accept or even celebrate extrajudicial methods. The lessons from this period extend far beyond the Philippines. For democracies worldwide, the drug war demonstrates how quickly constitutional protections can erode when populist leaders successfully frame rights as obstacles to public safety. For international institutions, it reveals the limitations of human rights mechanisms when confronted with popular domestic policies. For communities affected by drug problems, it offers a cautionary tale about enforcement-first approaches that neglect public health and social welfare dimensions. Most importantly, the documentation efforts, legal challenges, and survivor testimonies that emerged during this period provide a template for resistance and memory-keeping that may ultimately determine whether such campaigns become entrenched or are recognized as tragic departures from democratic governance. The path forward requires not just institutional reforms but rebuilding social consensus around the value of human rights and due process—a reminder that democracy demands constant vigilance against the politics of fear and dehumanization, particularly when they target society's most vulnerable members.

Best Quote

“This is a book about the dead, and the people who are left behind. It is also a personal story, written in my own voice, as a citizen of a nation I cannot recognize as my own. The thousands who died were killed with the permission of my people. I am writing this book because I refuse to offer mine.” ― Patricia Evangelista, Some People Need Killing

Review Summary

Strengths: The review praises the book as a brave piece of journalism and appreciates the author's focus on details, which aids in memory retention and understanding. The reviewer, an English teacher, also commends the effective and precise use of language, particularly the emphasis on certain words and phrases in their native context. Weaknesses: The review criticizes the book for not providing new insights about Rodrigo Duterte beyond his violent reputation. The extensive descriptions of brutal murders become overwhelming and lack a conclusive narrative, leaving the reader desiring a resolution. Overall Sentiment: Mixed. The reviewer expresses a range of emotions, including horror, sadness, and disappointment, but also acknowledges the value of the detailed narrative and language use. Key Takeaway: While the book is a courageous journalistic effort with strong language and detail, it ultimately fails to deliver new insights or a satisfying conclusion about Duterte's actions.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.