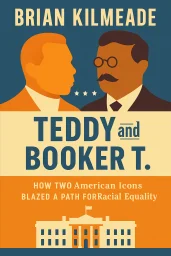

Teddy and Booker T.

How Two American Icons Blazed a Path for Racial Equality

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Politics, Audiobook, Americana, Book Club, Historical, Presidents, American History

Content Type

Book

Binding

Kindle Edition

Year

2023

Publisher

Sentinel

Language

English

ASIN

B0BV62NDPV

ISBN

0593543823

ISBN13

9780593543832

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Teddy and Booker T. Plot Summary

Introduction

In the fading light of the nineteenth century, two men from vastly different worlds forged an alliance that would challenge America's racial boundaries. Booker T. Washington, born into slavery with no surname to call his own, and Theodore Roosevelt, scion of Manhattan privilege, seemed unlikely partners in any endeavor. Yet these two extraordinary individuals—one who slept on a dirt floor as a child, the other raised in a brownstone mansion—would come together at a pivotal moment in American history. Their relationship, culminating in a controversial White House dinner in 1901, represented both the possibilities and limitations of racial progress in an era of hardening segregation. Their parallel journeys reveal remarkable similarities beneath obvious differences. Both were men of boundless energy and iron determination who overcame profound personal challenges—Washington rising from slavery to build an educational empire, Roosevelt conquering debilitating asthma to embody the "strenuous life." Both understood the power of personal example and pragmatic compromise. Through their unlikely friendship, we witness America's painful struggle with its racial divide, the courage required to challenge convention, and the complex calculations leaders must make when pushing against the boundaries of their time. Their story offers enduring lessons about the nature of social change and the delicate balance between principle and pragmatism.

Chapter 1: From Humble Beginnings: Contrasting Origins

Booker T. Washington entered the world around 1856 on a small plantation in Franklin County, Virginia. Born into slavery, his earliest memories were of a crude one-room cabin with a dirt floor that doubled as the plantation kitchen. He had no birthday to celebrate, no surname to claim as his own, and no prospects beyond servitude. Young Booker's daily tasks included carrying water to workers in the fields and fanning flies from his master's table during meals. At night, he slept on a bundle of rags in the corner of the cabin, a stark beginning for a man who would one day dine at the White House. When emancipation came in 1865, it brought freedom but little else. The Washington family moved to Malden, West Virginia, where Booker's stepfather had found work in the salt furnaces. Despite working grueling twelve-hour shifts in the furnaces and later the coal mines, young Booker harbored an insatiable hunger for education. He taught himself the alphabet from an old spelling book and convinced his mother to acquire a copy of Webster's "blue-back speller." Rising before dawn, he would study for an hour before beginning his workday, often continuing his lessons by the light of the furnace fires. Theodore Roosevelt's early years unfolded in dramatically different circumstances. Born on October 27, 1858, into one of New York City's wealthiest families, young "Teedie" grew up in a four-story brownstone on East 20th Street. His father, Theodore Sr., was a prominent businessman and philanthropist; his mother, Martha "Mittie" Bulloch, came from a distinguished Southern family. Roosevelt enjoyed every material advantage—private tutors, extensive travel, and a household staff that included a cook, coachman, and several maids. His childhood bedroom contained more books than most Americans would read in a lifetime. Yet privilege did not shield Roosevelt from suffering. From an early age, he endured debilitating asthma attacks that frequently left him gasping for breath in the middle of the night. His father would sometimes carry him through the house in the small hours, or take him on carriage rides through the city streets, seeking any relief for his son's constricted lungs. These episodes fostered both a deep bond between father and son and a determination in young Theodore to overcome physical weakness. When his father told him, "You have the mind but not the body; without the help of the body, the mind cannot go as far as it should," Roosevelt took the message to heart, embarking on a lifelong quest to build his physical strength through sheer force of will. For Washington, the path to advancement came through education. At age sixteen, having heard about Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, he set out on a journey of nearly 500 miles, much of it on foot. Arriving dirty and exhausted, with just fifty cents in his pocket, he impressed the head teacher by thoroughly cleaning a classroom as his entrance "examination." At Hampton, under the guidance of General Samuel Chapman Armstrong, Washington embraced a philosophy that would guide his life's work: education should develop "head, hand, and heart," combining academic knowledge with practical skills and moral character. Roosevelt's educational journey followed a more traditional elite path. After private tutoring, he attended Harvard College, where he distinguished himself through intellectual curiosity and boundless energy. Despite his privileged background, Roosevelt was not merely a dilettante. He completed a four-year program in three years while also writing his first book, "The Naval War of 1812," a scholarly work that established his reputation as a serious historian. From these vastly different beginnings, both men would forge paths to national prominence, their unlikely trajectories eventually converging at the highest levels of American society.

Chapter 2: Self-Made Men: Overcoming Personal Adversity

The death of Theodore Roosevelt's father in February 1878 marked a devastating turning point in the young man's life. At just nineteen, Roosevelt lost his hero and greatest champion. Writing in his diary that night, he noted simply: "He was a great man, a good citizen and the best of fathers." The loss left him adrift, questioning his direction in life. Though he inherited substantial wealth, Roosevelt refused to live as a gentleman of leisure. Instead, he channeled his grief into action, accelerating his studies at Harvard and plunging into politics upon graduation. By age twenty-three, he had won election to the New York State Assembly, becoming the youngest legislator in Albany. Booker Washington faced adversity of a different kind. After graduating from Hampton Institute in 1875, he taught school in his hometown before being invited to establish a new school for Black students in Tuskegee, Alabama. When he arrived in 1881, he found no school buildings, no equipment, and little funding—just a promise of $2,000 annually from the state legislature for teachers' salaries. Classes began in a dilapidated shanty and an old church, with thirty students, mostly adults who had never before attended school. Washington himself taught all subjects while simultaneously raising funds, recruiting faculty, and acquiring land for a permanent campus. Both men endured profound personal tragedies that tested their resilience. In 1884, Roosevelt experienced what he later called "the light going out of my life" when his mother and his young wife Alice died on the same day—his mother from typhoid fever and Alice from kidney failure after giving birth to their daughter. Devastated, Roosevelt handed his infant daughter to his sister, abandoned his political career, and fled to the Dakota Badlands, where he established a cattle ranch and reinvented himself as a cowboy and frontier lawman. The harsh landscape matched his inner desolation, but the physical demands of ranch life provided a path through grief. Washington too knew the pain of loss. His first wife, Fannie Smith, died in 1884, leaving him with a young daughter to raise. Later, his second wife, Olivia Davidson, who had been instrumental in helping build Tuskegee, succumbed to tuberculosis in 1889. Through these personal tragedies, Washington maintained his focus on building Tuskegee Institute, working eighteen-hour days and traveling constantly to raise funds. His third marriage, to Margaret Murray in 1893, provided stability and a capable partner who managed the school during his frequent absences. What distinguished both men was their extraordinary capacity for work. Roosevelt's energy was legendary—he was described as "a steam engine in trousers." During his time in the Dakota Badlands, he worked alongside cowboys, hunted buffalo, captured outlaws, and wrote three books. When a blizzard wiped out his cattle investment in 1886, he returned to New York, resumed his political career, and married his childhood friend Edith Carow, with whom he would have five more children. Washington's work ethic was equally impressive. At Tuskegee, he taught classes, supervised construction projects, raised funds, and handled correspondence, often working until midnight before rising at 4:00 a.m. to begin again. By the 1890s, both men had transformed themselves through the force of their will. Roosevelt had overcome physical frailty to become a robust outdoorsman and rising political star. Washington had built Tuskegee from nothing into a campus with multiple buildings, hundreds of students, and growing national recognition. Both embodied the American ideal of the self-made man, though they had started from vastly different places. Their parallel journeys of personal reinvention prepared them for the national roles they would soon assume—Roosevelt as the youngest president in American history, Washington as the most influential Black leader of his generation.

Chapter 3: Rising to National Prominence: The 1890s

In September 1895, Booker T. Washington delivered a speech that would catapult him to national prominence. Invited to address the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Washington seized the opportunity to present his vision for race relations to a mixed audience of whites and Blacks—itself a rarity in the segregated South. In what became known as the "Atlanta Compromise" speech, he urged Black Americans to "cast down your bucket where you are"—to focus on economic self-improvement rather than political agitation. Using the metaphor of a hand, he suggested that in all things essential to mutual progress, the races could be "as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress." The speech electrified the audience. White Southerners applauded Washington's apparent acceptance of segregation and his emphasis on industrial education rather than social equality. Northern industrialists appreciated his promotion of economic development and social stability. Black Americans had mixed reactions—many embraced his practical approach, while others criticized what they saw as an accommodation to white supremacy. Regardless, the speech transformed Washington into the most prominent Black leader in America. President Grover Cleveland sent him a congratulatory telegram, and invitations poured in from across the country. Theodore Roosevelt's path to national prominence took a different route. After serving as Civil Service Commissioner under Presidents Harrison and Cleveland, he became Police Commissioner of New York City in 1895. In this role, he implemented reforms to combat corruption, walking the streets at night to ensure officers were on duty and insisting on hiring based on merit rather than political connections. His crusading style and quotable pronouncements made him a favorite of newspaper reporters, building his national reputation as a reformer unafraid to challenge entrenched interests. The Spanish-American War of 1898 provided Roosevelt with the heroic credentials that would propel him to the highest office. Serving as Assistant Secretary of the Navy under President McKinley, Roosevelt had been a vocal advocate for military preparedness. When war was declared, he made the dramatic decision to resign his position to form the First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, known as the "Rough Riders." This colorful regiment combined Western cowboys, Eastern blue bloods, Native Americans, and former adversaries from both North and South. Leading his men in the famous charge up San Juan Hill in Cuba, Roosevelt demonstrated physical courage under fire. Though the actual military significance of the battle was modest, Roosevelt's dramatic accounts of the "crowded hour" of combat captured the public imagination. Washington, meanwhile, was building his own form of power through institution-building and network cultivation. By 1900, Tuskegee Institute had grown to more than 1,500 students and 100 faculty members, with an annual budget of $100,000. Washington had become a skilled fundraiser, cultivating relationships with wealthy Northern philanthropists like Andrew Carnegie, who donated $600,000 to Tuskegee, and John D. Rockefeller. He established a network of loyal graduates and supporters known as the "Tuskegee Machine," which influenced Black newspapers, churches, and businesses across the country. Both men understood the power of the written word. Washington's autobiography, "Up From Slavery," published in 1901, became a bestseller, further cementing his status as the preeminent Black leader. The book's narrative of overcoming adversity through hard work and determination resonated with American values and introduced Washington's life story to a broad audience. Roosevelt was equally prolific, having written numerous books on history, biography, and outdoor life. His accounts of hunting and ranching in the West helped create the masculine ideal that would become associated with his presidency. By the turn of the century, both men had positioned themselves as influential voices in American life. Roosevelt, returning from Cuba a war hero, was elected governor of New York in 1898 and vice president under McKinley in 1900. Washington had established himself as the most influential Black American, with access to presidents, industrialists, and philanthropists. Their paths, which had begun so far apart, were about to converge in a way that would challenge the racial conventions of their era.

Chapter 4: The White House Dinner: Breaking Racial Barriers

On September 6, 1901, President William McKinley was shot by an anarchist named Leon Czolgosz while attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. Eight days later, McKinley died of his wounds, and Theodore Roosevelt, at age 42, became the youngest president in American history. That very day, Roosevelt wrote a letter to Booker T. Washington, expressing regret that his planned visit to Tuskegee Institute would have to be postponed and adding, "I want to talk over the question of possible appointments in the south exactly on the lines of our last conversation together." This letter marked the beginning of an unprecedented relationship between a U.S. president and a Black leader. Roosevelt, who had met Washington briefly during his time as governor of New York, recognized that Washington's intimate knowledge of the South and his standing among both races made him an invaluable advisor. Washington, for his part, saw in Roosevelt a potential ally who might use federal appointments to advance the interests of Black Americans in a region where they were increasingly disenfranchised. On October 16, 1901, just weeks after taking office, Roosevelt invited Washington to dinner at the White House. The invitation was extended casually—Roosevelt later said, "I asked him to dinner as I would any other gentleman." Washington accepted, and that evening, he dined with the president, First Lady Edith Roosevelt, and their children. After the meal, the two men retired to discuss potential federal appointments in the South. For Washington, who had been born into slavery just forty-five years earlier, sitting as an equal at the president's table represented a remarkable personal journey and a symbolic milestone for Black Americans. Neither man anticipated the firestorm that would follow. The next morning, the Associated Press reported simply: "Booker T. Washington, of Tuskegee, Alabama, dined with the President last evening." This brief statement ignited a furious reaction across the South. The Memphis Scimitar declared it "the most damnable outrage that has ever been perpetrated by any citizen of the United States." Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina proclaimed that it would "necessitate our killing a thousand negroes in the South before they will learn their place again." Newspapers across the region published cartoons depicting the dinner in grotesque, racist terms. The dinner represented a profound breach of Southern racial etiquette. While Washington had dined with prominent whites in the North and even taken tea with Queen Victoria during a European tour, the White House dinner carried symbolic weight as an official recognition of social equality. Many Southern newspapers fixated particularly on the presence of Edith Roosevelt at the table, viewing it as an insult to white womanhood—a theme that resonated powerfully in a region obsessed with maintaining racial boundaries through the prevention of social mixing. Roosevelt was genuinely surprised by the intensity of the backlash. "The outburst of feeling in the South," he wrote to a friend, "is to me literally inexplicable." Publicly, he maintained a dignified silence, refusing to comment on what he considered a private matter. Privately, he assured Washington that he "did not care a snap of his finger what anybody said or thought about it." Washington, more familiar with Southern racial attitudes, maintained an equally discreet silence, later writing that "for days and weeks I was pursued by reporters in quest of interviews... but during the whole of this period of agitation and excitement I did not give out a single interview and did not discuss the matter in any way." Despite Roosevelt's initial defiance, the political reality was inescapable. The dinner had damaged his standing in the South and complicated his plans to build Republican support in the region. Though he continued to consult Washington on appointments and policy matters, Roosevelt never again invited him or any other Black person to dine at the White House during his presidency. The episode revealed the limits of even a progressive president's ability to challenge the racial conventions of the era, while also demonstrating how deeply entrenched those conventions remained more than three decades after the Civil War.

Chapter 5: Behind the Scenes: Their Working Relationship

In the years following the White House dinner, Roosevelt and Washington developed a working relationship that was unprecedented in American history. Washington became an unofficial advisor to the president, recommending candidates for federal positions throughout the South. Between 1901 and 1909, Roosevelt appointed more Black Americans to federal office than any previous president, including William D. Crum as collector of customs in Charleston, South Carolina, and Robert H. Terrell as a judge in Washington, D.C. Many of these appointments came at Washington's suggestion. Their correspondence reveals a relationship based on mutual respect and shared political goals. Roosevelt valued Washington's intimate knowledge of Southern conditions and his ability to identify qualified candidates who would serve with distinction. In one letter, Roosevelt wrote, "There is not a single one of the appointments which has not been made on the ground of merit and of merit alone." Washington, for his part, appreciated Roosevelt's willingness to consider Black appointees on their merits rather than rejecting them solely because of race. He wrote to a friend that Roosevelt was "the first President who has taken any considerable interest in the welfare of the Negro since the death of Lincoln." The most dramatic confrontation came in Indianola, Mississippi, where Minnie Cox, a Black woman who had served effectively as postmaster since 1891, was forced to resign after white citizens threatened her life. Roosevelt refused to accept her resignation and instead closed the Indianola post office, rerouting mail to other locations. This bold action demonstrated Roosevelt's willingness to use federal power to defend the principle of merit-based appointments, regardless of race. Washington privately applauded the president's stand, writing, "You have taught the country a lesson that will not soon be forgotten." Their alliance extended beyond appointments. Washington advised Roosevelt on racial issues and helped shape the president's public statements. When Roosevelt visited Tuskegee Institute in 1905, Washington arranged an elaborate welcome, with students demonstrating their skills in various trades and Roosevelt praising the school as "a focus of civilization." The visit symbolized Roosevelt's respect for Washington's educational work, even as political realities limited their broader collaboration. Yet their relationship was not without tensions. Washington sometimes found himself in the difficult position of defending Roosevelt's actions to the Black community while privately urging the president to take stronger stands. When Roosevelt dishonorably discharged an entire battalion of Black soldiers after the Brownsville incident in 1906, Washington was deeply troubled. He wrote to Roosevelt, warning that it would be "a great blunder," but the president rejected his counsel. The episode revealed the limits of Washington's influence and the constraints under which both men operated. Their partnership was fundamentally pragmatic. Washington understood that in the political climate of the early 1900s, direct challenges to segregation would provoke backlash without producing meaningful change. He chose instead to work within the system, using his access to power to secure incremental gains. Roosevelt, while more progressive on race than most white politicians of his era, was unwilling to sacrifice his broader political agenda for racial justice. He balanced symbolic gestures of racial equality with practical concessions to Southern white sentiment. Despite these limitations, the Roosevelt-Washington alliance represented a significant departure from previous presidential approaches to race. Their working relationship demonstrated that a Black leader could influence federal policy and that a white president could recognize Black talent and achievement. In an era when racial violence was increasing and segregation was becoming more entrenched, their pragmatic partnership created small openings for Black advancement and established precedents that would influence future civil rights efforts.

Chapter 6: Navigating Jim Crow: Pragmatism and Principle

The early 1900s marked one of the darkest periods in American race relations. The promise of Reconstruction had given way to the harsh realities of Jim Crow segregation. Between 1890 and 1910, Southern states systematically disenfranchised Black voters through poll taxes, literacy tests, and "grandfather clauses." Lynchings reached their peak, with over 100 Black Americans killed by mob violence annually. The Supreme Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson had sanctioned "separate but equal" facilities, giving legal cover to segregation laws that were rapidly spreading across the South. Within this hostile environment, Washington and Roosevelt pursued different strategies for addressing racial inequality. Washington's approach emphasized economic self-improvement and institution-building rather than direct challenges to white supremacy. His famous metaphor from the Atlanta speech—"separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand"—reflected his belief that Black Americans should focus first on economic independence before demanding social equality. "The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera house," he often said. This accommodationist approach won Washington support from white philanthropists and politicians while allowing him to build Tuskegee into a powerful institution for Black advancement. Yet it also drew increasing criticism from other Black leaders. W.E.B. Du Bois, a Harvard-educated scholar, emerged as Washington's most formidable critic. In his 1903 book "The Souls of Black Folk," Du Bois argued that Washington's strategy had led to "the disfranchisement of the Negro, the legal creation of a distinct status of civil inferiority for the Negro, and the steady withdrawal of aid from institutions for the higher training of the Negro." Roosevelt, protected by his race, wealth, and position, could afford to be more outspoken on racial issues, though he too was constrained by political realities. He believed in what he called "equality of opportunity," arguing that race should not determine a person's chances in life. "I have not been able to think out any solution of the terrible problem offered by the presence of the Negro on this continent," he once wrote, "but of one thing I am sure, and that is that inasmuch as he is here and can neither be killed nor driven away, the only wise and honorable and Christian thing to do is to treat each black man and each white man strictly on his merits as a man." This principle led Roosevelt to make several groundbreaking appointments of Black Americans to federal positions. When Southern senators blocked William Crum's confirmation as collector of customs in Charleston, Roosevelt stood firm, declaring: "I cannot consent to take the position that the door of hope—the door of opportunity—is to be shut upon any man, no matter how worthy, purely upon the grounds of race or color." Yet Roosevelt's commitment to racial equality had significant limits. He accepted the reality of segregation in the South and did not push for federal civil rights legislation. Washington, for his part, maintained a public persona of moderation while working privately for change. Unknown to most contemporaries, he secretly funded court cases against discriminatory laws and provided financial support to anti-lynching campaigns. When a Black man was lynched near Tuskegee, Washington published careful statements condemning mob violence without directly challenging white supremacy. Yet behind the scenes, he gathered evidence about the lynching and forwarded it to Northern newspapers, helping to mobilize public opinion against the practice. Both men recognized the dangers of direct confrontation in an era when racial violence was commonplace. Washington had witnessed the failure of more militant approaches during Reconstruction and believed that economic advancement would eventually lead to political rights. Roosevelt, while sympathetic to Black aspirations, was unwilling to sacrifice his broader political agenda for racial justice. Their pragmatic approach frustrated more radical voices like Du Bois, who demanded immediate action on civil rights, but it reflected a realistic assessment of what was possible in the Jim Crow era. The tension between pragmatism and principle defined both men's approaches to racial issues. Washington's famous advice to "cast down your bucket where you are" reflected his belief that Black Americans needed to build from their current position rather than waiting for external salvation. Roosevelt's declaration that he would not "close the door of hope" to qualified Black Americans expressed his conviction that merit should trump prejudice. Both sought to navigate the treacherous waters of American race relations without capsizing the vessels that carried their broader ambitions—Tuskegee Institute for Washington, the Republican Party and progressive reform for Roosevelt.

Chapter 7: Diverging Legacies: Impact on American Race Relations

As Roosevelt's presidency drew to a close in 1909, both he and Washington faced diminishing influence. Roosevelt, honoring his pledge not to seek a third term, handed the presidency to his chosen successor, William Howard Taft. Washington continued to lead Tuskegee Institute and maintain his network of influence, but his accommodationist approach seemed increasingly out of step with the growing militancy of younger Black leaders. The formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909, with W.E.B. Du Bois as its director of publicity and research, signaled a shift toward more direct challenges to segregation and discrimination. The two men's paths diverged further in the years that followed. Roosevelt, dissatisfied with Taft's conservative policies, broke with his successor and formed the Progressive Party to run for president again in 1912. The campaign split the Republican vote, allowing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency. Wilson, a Southerner with segregationist views, proceeded to reverse many of Roosevelt's modest advances in racial equality, segregating federal offices and dismissing most Black appointees. Roosevelt's political career never fully recovered from this defeat. Washington maintained his public stance of accommodation while privately supporting legal challenges to segregation and disfranchisement. Yet his health was failing. Years of constant travel and overwork had taken their toll, and in November 1915, at age 59, Booker T. Washington died of high blood pressure and kidney disease. His funeral at Tuskegee drew thousands of mourners, both Black and white. Roosevelt issued a statement praising Washington as "one of the most useful citizens of our land" who had "rendered greater service to his race than had ever been rendered by any one else." Three years later, in January 1919, Roosevelt himself died at his home in Oyster Bay, New York, at age 60. The legacies of both men proved complex and enduring. Roosevelt is remembered as a progressive president who expanded the power of the federal government to address social and economic problems. His conservation efforts preserved millions of acres of public land, and his "Square Deal" policies sought to balance the interests of labor, business, and consumers. Yet his record on race was mixed at best. While he invited Washington to the White House and appointed some Black officials, he also accommodated Southern racism and betrayed the Black soldiers in the Brownsville affair. Washington's legacy has been even more contested. For decades after his death, he was widely celebrated as the greatest Black leader since Frederick Douglass. Schools, streets, and monuments across America bore his name. Yet the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s embraced Du Bois's more confrontational approach, and Washington came to be viewed by many as an accommodationist who had compromised too much with white supremacy. Martin Luther King Jr., while acknowledging Washington's contributions, criticized his "doctrine of accommodation" as insufficient for achieving true equality. More recent scholarship has offered a more nuanced assessment of both men. Washington's emphasis on education, economic self-sufficiency, and institution-building provided essential foundations for later civil rights advances. His behind-the-scenes activism revealed a more complex figure than his public persona suggested. Roosevelt's willingness to challenge some aspects of racial prejudice, while limited by today's standards, represented a significant departure from the policies of his predecessors and successors. Their relationship demonstrated both the possibilities and the severe constraints of interracial cooperation in the early twentieth century. The White House dinner, though it produced a backlash that revealed the depths of American racism, had symbolic importance as a moment when the highest office in the land recognized the dignity and accomplishments of a Black American. Their pragmatic alliance, while falling far short of true equality, created small openings in the wall of segregation and established precedents that would influence future civil rights efforts. Neither man fully transcended the prejudices of their era, but both pushed against its boundaries in ways that would influence future generations of Americans seeking to fulfill the nation's promise of equality for all. Their story reminds us that progress often comes through imperfect compromises and that leaders must navigate between the world as it is and the world as it should be.

Summary

The unlikely alliance between Booker T. Washington and Theodore Roosevelt represents a pivotal chapter in America's long struggle with its racial divide. Their relationship, crystallized in that controversial White House dinner of 1901, challenged the rigid social codes of their era while revealing their limitations. Washington, rising from slavery to become the most influential Black leader of his generation, advocated a pragmatic approach to racial advancement through education and economic self-improvement. Roosevelt, overcoming childhood illness to become the youngest president in American history, demonstrated both courage and caution in addressing racial issues, appointing Black officials while accommodating Southern white sensibilities. Their legacy offers a profound lesson in the complexities of social change. Both men understood that progress requires both visionary leadership and practical compromise, that principles must sometimes bend to political reality without breaking. Their story reminds us that even incremental advances matter in the long arc toward justice, and that leadership often means navigating between the world as it is and the world as it should be. For contemporary Americans still grappling with racial divisions, Washington and Roosevelt's imperfect alliance demonstrates that meaningful progress often comes through unlikely partnerships and the willingness to take risks, however calculated, for a more equitable society.

Best Quote

“I would rather go out of politics having the feeling that I had done what was right than stay in with the approval of all men, knowing in my heart that I had acted as I ought not to. Theodore Roosevelt, March 1883 With” ― Brian Kilmeade, Teddy and Booker T.: How Two American Icons Blazed a Path for Racial Equality

Review Summary

Strengths: The book aims to pique interest in historical figures, and it includes a reading list for further exploration. The author, Brian Kilmeade, effectively parallels the life stories of Theodore Roosevelt and Booker T. Washington.\nWeaknesses: The book attempts to cover too much US history in a short format, resulting in a lack of depth. The narrative is described as scattershot, with significant events, such as the meeting of Washington and Roosevelt, occurring late in the book. The condensed nature of the book is also seen as a drawback.\nOverall Sentiment: Mixed\nKey Takeaway: While the book may serve as an introductory piece to spark interest in the lives of Washington and Roosevelt, it suffers from a lack of depth due to its condensed format, which may not satisfy readers looking for a comprehensive historical account.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.