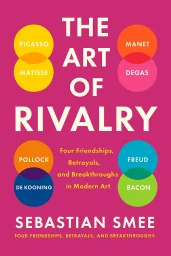

The Art of Rivalry

Four Friendships, Betrayals, and Breakthroughs in Modern Art

Categories

Nonfiction, Art, Biography, History, Unfinished, Audiobook, Book Club, Historical, Art Design, Art History

Content Type

Book

Binding

Kindle Edition

Year

2016

Publisher

Random House

Language

English

ASIN

B018CHH1WM

ISBN

0812994817

ISBN13

9780812994810

File Download

PDF | EPUB

The Art of Rivalry Plot Summary

Introduction

Throughout history, empires have risen and fallen in a grand dance of power that has shaped our world in profound ways. From the ancient Persian Empire's innovative administrative systems to the digital networks of today's global powers, imperial ambitions have driven human civilization forward while exacting terrible costs. These vast political entities have connected distant regions through trade, spread technologies and ideas across continents, and created enduring cultural legacies that outlived their political structures. Yet they have also brought conquest, exploitation, and suffering to countless peoples caught in their expansionist drives. This sweeping historical narrative explores how imperial systems have evolved over 2,500 years, revealing patterns that repeat across civilizations and eras. Readers will discover how successful empires balanced central control with local autonomy, how religious and commercial networks sometimes proved more durable than military conquest, and how technological innovations repeatedly shifted the balance of global power. Whether you're a student of international relations seeking historical context for today's geopolitical tensions or simply curious about how our interconnected world came to be, this exploration of imperial ambition offers valuable insights into both our past and our possible futures.

Chapter 1: Ancient Foundations: The First Imperial Networks (500 BCE-200 CE)

The ancient world witnessed the emergence of history's first imperial networks, setting patterns that would echo through millennia. From 500 BCE to 200 CE, several remarkable political systems developed sophisticated methods of control that extended far beyond simple military conquest. The Persian Empire, established by Cyrus the Great, pioneered techniques of imperial administration that respected local customs while ensuring loyalty through carefully calibrated tribute systems. Rather than imposing uniform governance, Persian rulers maintained stability by allowing cultural autonomy within a framework of ultimate imperial authority. In the Mediterranean, Rome's expansion from city-state to world power represented a different model. Beginning as a republic dominated by competing aristocratic families, Rome gradually developed institutions that could project power across vast distances. The Roman road system, spanning over 250,000 miles at its height, represented not just an engineering marvel but a revolutionary approach to imperial communication. Messages could travel up to 150 miles per day, allowing unprecedented coordination across three continents. This infrastructure enabled Rome's distinctive approach to provincial management, where local elites were gradually incorporated into Roman citizenship through a process that one provincial governor described as "making the whole world a single city." The Han Dynasty in China, meanwhile, developed perhaps the most sophisticated bureaucratic system of the ancient world. Unlike Rome's reliance on semi-autonomous local elites, Han emperors established a centralized examination system that selected officials based on merit rather than birth. This innovation created a class of educated administrators whose primary loyalty was to the imperial system itself rather than regional interests. The Han also pioneered the use of census-taking and standardized currency, creating an integrated economic space that facilitated trade across Asia. What these imperial systems shared was their ability to create networks of power that transcended simple military domination. Each developed sophisticated ideologies that justified their rule - whether Rome's concept of bringing civilization to "barbarians," Persia's tolerance of religious diversity, or China's Confucian emphasis on harmony and proper relationships. These ideological frameworks proved remarkably durable, often outlasting the political structures that created them. When Rome eventually fell, its cultural and legal legacy continued to shape European civilization for centuries. The limits of these ancient imperial systems are equally instructive. Despite their impressive achievements, each struggled with the fundamental tension between centralized control and local autonomy. Distance imposed practical constraints on imperial power, creating opportunities for rebellion in peripheral regions. The costs of maintaining vast military establishments eventually strained even the most sophisticated economic systems. And succession problems - the challenge of peacefully transferring power - plagued every imperial system, frequently leading to civil wars that weakened the state against external threats. These patterns of imperial rise and decline would repeat throughout history, as ambitious leaders continually attempted to solve the fundamental problems of large-scale political organization.

Chapter 2: Faith and Trade: New Connections Emerge (200-800)

As the ancient imperial systems fragmented between 200 and 800 CE, new forms of connection emerged that would reshape human history. This period witnessed the rise of universal religions and trading networks that created different kinds of power - ones based not on territorial control but on shared beliefs and economic integration. Christianity spread from an obscure sect in the Roman Empire to become the dominant religion of Europe, while Islam emerged from the Arabian Peninsula to create a new civilization stretching from Spain to Central Asia. These faith traditions created communities that transcended political boundaries, establishing alternative sources of authority and identity. The Silk Roads connecting China to the Mediterranean became highways not just for luxury goods but for ideas, technologies, and diseases. Chinese innovations like paper-making techniques traveled westward, while Greek philosophical concepts moved east. Merchants from different cultural backgrounds developed sophisticated financial instruments like letters of credit and partnerships that allowed trade to flourish despite political fragmentation. In port cities like Alexandria, Constantinople, and Guangzhou, cosmopolitan communities emerged where multiple languages, religions, and customs coexisted. These commercial hubs often enjoyed significant autonomy from imperial centers, developing their own political traditions based on pragmatic cooperation rather than ideological uniformity. The Byzantine Empire, continuing the eastern Roman tradition, demonstrated remarkable adaptability during this period. Facing threats from all directions, Byzantine rulers reformed their administrative systems, developed new military tactics, and cultivated diplomatic relationships that played rivals against each other. The empire's survival for a millennium after Rome's fall in the west testifies to the effectiveness of these flexible approaches to power. Byzantine emperors understood that imperial survival required constant adaptation rather than rigid adherence to tradition. In China, the Tang Dynasty (618-907) created perhaps the most sophisticated civilization of its era, combining military power with cultural brilliance. The Tang capital of Chang'an, with over a million inhabitants, was the world's largest city, attracting merchants, scholars, and religious figures from across Asia. Tang rulers patronized Buddhism while maintaining Confucian administrative traditions, creating a syncretic culture that influenced neighboring societies from Korea to Vietnam. The dynasty's openness to foreign influences contributed to remarkable innovations in everything from poetry to ceramics. The period also witnessed significant shifts in economic organization. As centralized states weakened in Europe and parts of Asia, local lords established control over peasant populations, creating what historians would later call feudal relationships. These arrangements provided security in dangerous times but at the cost of restricting mobility and innovation. In contrast, the Islamic world maintained more urbanized economies with sophisticated commercial practices, laying foundations for later economic developments. The contrast between these systems would have profound implications for future power relationships. By 800 CE, the world had become more interconnected than ever before, but in ways fundamentally different from the territorial empires of antiquity. Religious networks, commercial relationships, and cultural exchanges created complex webs of influence that no single political authority could control. This diffusion of power created space for new forms of organization and identity to emerge, setting the stage for the next phase of imperial development. The lesson was clear: power could flow through channels other than formal political structures, and sometimes these alternative networks proved more durable than empires themselves.

Chapter 3: Maritime Expansion and Competing Empires (1400-1650)

The period from 1400 to 1650 witnessed one of history's most dramatic reconfigurations of global power. European maritime expansion connected previously separate regions into the first truly global networks of exchange, with profound and often devastating consequences. Portuguese navigators pioneered sea routes around Africa to Asia, while Spanish conquistadors established empires in the Americas. These voyages were made possible by technological innovations like the caravel ship and advances in navigation, but equally important were institutional innovations in financing and organizing these high-risk ventures. Joint-stock companies allowed investors to pool resources and share risks, creating new forms of economic organization that would eventually transform global commerce. The Columbian Exchange - the transfer of plants, animals, diseases, and people between hemispheres - reshaped ecosystems and societies worldwide. European diseases like smallpox devastated indigenous American populations, causing demographic collapses that in some regions exceeded 90 percent. This biological asymmetry facilitated European conquest more effectively than military technology. Meanwhile, American crops like potatoes, maize, and tomatoes gradually transformed diets and agricultural systems across Europe, Africa, and Asia, supporting population growth and changing patterns of land use. As one Spanish chronicler observed, "The world has become one, for a man can see with his own eyes what Ptolemy could not imagine." While Europeans were expanding outward, other powerful empires were consolidating control across Eurasia. The Ottoman Empire captured Constantinople in 1453, ending the thousand-year Byzantine legacy and establishing itself as a dominant Mediterranean power. Ottoman sultans developed sophisticated administrative systems that incorporated diverse religious and ethnic communities while maintaining Islamic political supremacy. Further east, the Safavid Empire in Persia and the Mughal Empire in India created similarly sophisticated political systems. The Mughal emperor Akbar (1556-1605) pioneered policies of religious tolerance and cultural synthesis that allowed his multi-faith empire to flourish, demonstrating that imperial success often depended on accommodating diversity rather than imposing uniformity. In East Asia, Ming Dynasty China initially conducted its own maritime expeditions under Admiral Zheng He, whose treasure ships dwarfed European vessels. These voyages, reaching as far as East Africa, demonstrated China's technological superiority and projected imperial prestige across the Indian Ocean world. However, the Ming court eventually abandoned these expeditions, focusing instead on continental threats and internal development. This decision, much debated by historians, reflected different imperial priorities rather than technological limitations. The Ming state directed its considerable resources toward infrastructure projects like the Grand Canal and the renovation of the Great Wall, strengthening internal integration rather than overseas expansion. The period also saw significant intellectual developments that would reshape how empires understood themselves and their place in the world. The Renaissance and Reformation in Europe challenged traditional authorities and created new frameworks for understanding humanity's relationship to the divine and natural worlds. Similar intellectual ferment occurred in other civilizations, from Neo-Confucian philosophy in China to syncretic religious movements in the Islamic world. These intellectual currents both reflected and influenced changing patterns of imperial power, as rulers sought new ideological foundations for their authority. By 1650, the foundations had been laid for a new world order dominated by competing imperial systems with global reach. European powers had established footholds on every continent, creating extractive economies that channeled resources toward imperial centers. Yet European dominance remained limited, as powerful Asian empires continued to control the majority of the world's population and wealth. The stage was set for increasingly intense imperial competition that would eventually transform not just political boundaries but the fundamental nature of human societies worldwide.

Chapter 4: Revolution and Industry: Transforming Imperial Power (1750-1848)

The century between 1750 and 1848 witnessed revolutionary transformations that fundamentally altered the nature of imperial power. The Industrial Revolution, beginning in Britain, created unprecedented disparities in productive capacity between industrializing and non-industrializing regions. Steam power, mechanized production, and new transportation technologies like railways dramatically increased output while reducing costs. These changes gave industrializing powers enormous advantages in both economic competition and military capability. As one British industrialist noted after visiting India: "Their hand-spinning and hand-weaving are wonderful arts, but against steam and machinery, they have no chance." Political revolutions proved equally transformative. The American Revolution (1775-1783) established a new model of republican government that rejected monarchical authority while maintaining many imperial ambitions. The French Revolution (1789) went further, challenging the entire social and political order with its radical claims about liberty, equality, and popular sovereignty. These revolutionary ideologies spread far beyond their origins, inspiring independence movements throughout the Americas and reform efforts across Europe. The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), where enslaved people successfully overthrew both slavery and colonial rule, demonstrated that revolutionary principles could be claimed by those Europeans had considered property rather than people. The British Empire responded to these challenges by reinventing itself. After losing its American colonies, Britain shifted focus to Asia, where the East India Company gradually transformed from a trading enterprise to a territorial power controlling much of the Indian subcontinent. This "company state" represented a new form of imperial organization that blurred lines between public authority and private profit. British officials justified their expanding control with claims about bringing "improvement" and "civilization" to supposedly backward societies. This ideological shift from commerce to civilizing mission provided new rationales for imperial expansion even as revolutionary ideals challenged traditional imperial legitimacy. Napoleon Bonaparte's meteoric rise and fall demonstrated both the potential and limitations of personal imperial ambition in this revolutionary age. His conquests temporarily redrew the map of Europe and spread revolutionary legal codes across the continent. Yet his inability to consolidate these gains revealed the challenges of maintaining imperial control in an age of nationalism and popular mobilization. The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815), which reorganized Europe after Napoleon's defeat, attempted to restore traditional authority while accommodating new realities. This conservative reaction against revolutionary principles would shape European politics for decades. Latin American independence movements, led by figures like Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín, successfully ended Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule across most of the hemisphere by the 1820s. However, these new nations struggled to establish stable political systems, often oscillating between authoritarian and democratic tendencies. Economic dependence on European markets and technology created new forms of informal imperial influence even after formal colonial ties were severed. As Bolívar lamented near the end of his life, "America is ungovernable; those who served the revolution have plowed the sea." By 1848, when revolutionary uprisings swept across Europe, the fundamental tensions of the age remained unresolved. Industrial capitalism had created unprecedented wealth alongside new forms of exploitation. Revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality had inspired millions while threatening established orders. Imperial powers had developed new justifications for their rule even as subject peoples increasingly questioned foreign domination. These contradictions would intensify in the coming decades, as imperial competition reached new heights and revolutionary challenges continued to emerge from unexpected quarters. The age had demonstrated that imperial ambitions remained powerful, but also that they faced more sophisticated resistance than ever before.

Chapter 5: The Century of Total War and Decolonization (1914-1989)

The period from 1914 to 1989 witnessed the most destructive conflicts in human history, followed by a fundamental reorganization of global power structures. World War I (1914-1918) marked the culmination of imperial rivalries that had been building for decades. The conflict's unprecedented scale and brutality - with over 16 million deaths - shattered the confidence of European imperial powers. The war introduced industrial killing on a massive scale, from machine guns and poison gas to aerial bombardment. As one British officer wrote from the trenches: "This is not war; it is the ending of worlds." The Russian Revolution of 1917 established the Soviet Union as the world's first communist state, creating an ideological challenge to both liberal democracy and traditional imperialism. Lenin's analysis of imperialism as the "highest stage of capitalism" provided a powerful framework for anti-colonial movements worldwide. Meanwhile, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire led to a new imperial arrangement in the Middle East, where Britain and France established "mandates" over former Ottoman territories. These arrangements, justified as temporary guidance toward self-government, actually represented a new form of colonial control disguised with more acceptable terminology. The Great Depression beginning in 1929 demonstrated the interconnectedness of the global economy while revealing its fundamental instabilities. Economic collapse fueled political extremism, particularly in Germany, where Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime combined ultra-nationalism with imperial ambitions for "living space" in Eastern Europe. Japan similarly pursued an aggressive imperial policy in Asia, framing its conquests as liberation from Western imperialism while imposing its own harsh colonial rule. These revisionist powers directly challenged the imperial order established after World War I. World War II (1939-1945) surpassed even its predecessor in scale and destruction, with over 60 million deaths worldwide. The conflict's global nature - with major fighting across Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Pacific - demonstrated that imperial competition had truly become a worldwide phenomenon. The war's conclusion established the United States and Soviet Union as the dominant global powers, with traditional European empires fatally weakened. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki revealed that human technological capacity for destruction had reached apocalyptic proportions, fundamentally altering calculations about the costs of great power conflict. The Cold War that followed represented a new kind of imperial competition, where the superpowers sought to extend their influence without direct military confrontation. Both the American and Soviet systems offered competing visions of modernity and development to former colonial territories gaining independence. Decolonization accelerated dramatically, with most Asian and African territories achieving formal independence by the 1960s. However, economic dependence, military interventions, and ideological pressures often limited the practical sovereignty of these new nations. As Ghanaian leader Kwame Nkrumah observed, "neo-colonialism is the worst form of imperialism - for those who practice it, it means power without responsibility, and for those who suffer from it, it means exploitation without redress." The Cold War's conclusion with the Soviet Union's collapse in 1989-1991 marked the end of a bipolar world order that had structured international relations for decades. The United States emerged as the sole superpower, prompting premature declarations about "the end of history" and the universal triumph of liberal democracy and capitalism. Yet the legacy of the century's imperial conflicts and ideological battles continued to shape global politics. The period had demonstrated both the destructive potential of imperial ambition when combined with industrial technology and the resilience of human societies in recovering from unprecedented devastation. The question remained whether humanity had truly learned from this century of catastrophe or was merely entering a brief interlude before new forms of imperial competition emerged.

Chapter 6: Digital Age: Rebalancing Global Power (1989-Present)

The post-Cold War period has witnessed two parallel transformations that have fundamentally reshaped global power dynamics: the digital revolution and the economic rise of previously peripheral regions. The internet's emergence as a global communications platform created unprecedented opportunities for connection while disrupting traditional information hierarchies. Digital technologies enabled new forms of organization, from transnational social movements to global supply chains that distribute production across dozens of countries. These technologies initially appeared to favor democratic openness, but authoritarian regimes quickly adapted, developing sophisticated methods of surveillance and control. As one Chinese technology executive observed: "The Great Firewall was not built to keep information out, but to keep it contained and managed." China's extraordinary economic ascent represents the most significant shift in global economic power since the Industrial Revolution. From a poor, predominantly agricultural society in the 1980s, China transformed into the world's manufacturing center and second-largest economy. This development challenged assumptions about the necessary connection between capitalism and liberal democracy, as the Chinese Communist Party maintained political control while embracing market mechanisms. Other emerging economies, particularly India, Brazil, and several Southeast Asian nations, also experienced rapid growth, creating a more multipolar economic landscape than at any point in the past two centuries. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent "War on Terror" revealed the vulnerability of even the most powerful states to non-state actors. American military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq demonstrated both the overwhelming conventional military superiority of the United States and the limitations of that power in achieving political objectives. These conflicts, costing trillions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of lives, highlighted the immense difficulty of imposing external models of governance on societies with different historical experiences and cultural traditions. As one Iraqi politician remarked to American officials: "You have the watches, but we have the time." The 2008 global financial crisis exposed fundamental weaknesses in the economic system that had dominated the post-Cold War period. The crisis originated in the United States but quickly spread worldwide, demonstrating the interconnectedness of global financial markets. The subsequent policy responses - massive government interventions to stabilize banking systems - contradicted the free-market orthodoxy that had been promoted globally for decades. This ideological shock, combined with rising inequality within many societies, fueled populist movements challenging established political and economic arrangements in both developed and developing countries. Climate change emerged as perhaps the most fundamental challenge to existing patterns of development and consumption. The scientific consensus about human-caused global warming confronted humanity with a collective action problem of unprecedented scale and complexity. The uneven distribution of both historical responsibility for carbon emissions and vulnerability to climate impacts created difficult questions of justice and responsibility. Meanwhile, technological innovations in renewable energy offered potential pathways toward more sustainable development, though the pace of adoption remained insufficient to prevent significant warming. The COVID-19 pandemic beginning in 2020 further revealed both the interconnectedness of the modern world and the fragility of global systems. The virus spread rapidly along international travel routes, while disruptions to supply chains demonstrated the vulnerabilities created by economic interdependence. National responses varied dramatically, reflecting different governance capacities, cultural factors, and political priorities. The development and distribution of vaccines highlighted both remarkable scientific capabilities and profound inequities in access to life-saving technologies. As we move further into the 21st century, the fundamental tension between global integration and national sovereignty remains unresolved. Digital technologies simultaneously enable unprecedented connection and new forms of division. Economic development has lifted billions from poverty while creating new environmental challenges. The distribution of power - military, economic, technological, and cultural - continues to shift in ways that create both opportunities and dangers. The imperial ambitions that have shaped human history for millennia have not disappeared, but they now operate in a world where traditional forms of domination face greater constraints than ever before. The question remains whether humanity can develop forms of global cooperation adequate to address shared challenges without recreating the hierarchies and exploitations that characterized earlier imperial systems.

Summary

Throughout history, imperial ambition has been the primary engine driving large-scale political organization, technological innovation, and cultural exchange. From ancient Persia to modern America, ambitious leaders have sought to extend their power across ever-larger territories, creating systems that connected previously isolated regions. These imperial projects have followed remarkably consistent patterns: initial expansion fueled by military, technological, or organizational advantages; consolidation through administrative systems that balance central control with local autonomy; cultural flourishing as diverse traditions interact within imperial frameworks; and eventual decline as costs of maintenance exceed benefits, succession problems emerge, or new competitors develop superior capabilities. Yet each imperial system also adapted to its particular historical context, developing distinctive approaches to legitimacy, governance, and cultural integration. The most enduring lesson from this historical survey is that power is never absolute and always contested. Even at their heights, the most formidable empires faced resistance from those they sought to rule and competition from rival powers. The most successful imperial systems were those that adapted to changing circumstances rather than rigidly adhering to established patterns. Today, as humanity faces unprecedented global challenges from climate change to pandemic disease, this historical perspective offers valuable insights. Rather than seeking dominance through traditional imperial methods, contemporary powers might better secure their interests through developing cooperative frameworks that address shared vulnerabilities. The imperial impulse - the desire to extend control and impose order - remains powerful, but history suggests that sustainable systems must balance this ambition with respect for diversity and recognition of interdependence. Perhaps the true legacy of imperial dreams is not the monuments they built or territories they claimed, but the connections they created that now form the foundation for a genuinely global civilization.

Best Quote

“IF THERE IS A FUNDAMENTAL difference between rivalry in the modern era and rivalry in earlier epochs, as I believe there is, it is that in the modern era artists developed a wholly different conception of greatness. It was a notion based not on the old, established conventions of mastering and extending a pictorial tradition, but on the urge to be radically, disruptively original. Where did this urge come from? It was a response, most basically, to the new conditions of life—to a sense that modern, industrialized, urban society, although in some ways representing a pinnacle of Western civilization, had also foreclosed on certain human possibilities. Modernity, many began to feel, had shut off the possibility of forging a deeper connection with nature and with the riches of spiritual and imaginative life. The world, as Max Weber wrote, had become disenchanted. Hence” ― Sebastian Smee, The Art of Rivalry: Four Friendships, Betrayals, and Breakthroughs in Modern Art

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights an intriguing historical anecdote involving Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, which adds depth and interest to the narrative. The author, Sebastian Smee, is noted for effectively weaving this story into the broader context of artistic rivalry. Weaknesses: The review points out that the author repeats the story twice without providing a resolution to the mystery of Manet's actions, which might leave readers wanting more insight or analysis. Overall Sentiment: Mixed. The review appreciates the engaging storytelling but is critical of the lack of resolution and repetition. Key Takeaway: The book offers an engaging exploration of artistic relationships, illustrated by captivating anecdotes, but may fall short in providing comprehensive analysis or resolution to the stories it presents.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.