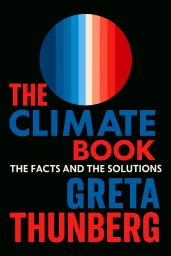

The Climate Book

The Facts and the Solutions

Categories

Nonfiction, Science, History, Politics, Nature, Audiobook, Sustainability, Environment, Ecology, Climate Change

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2023

Publisher

Penguin Press

Language

English

ASIN

0593492307

ISBN

0593492307

ISBN13

9780593492307

File Download

PDF | EPUB

The Climate Book Plot Summary

Introduction

Imagine standing in a laboratory in 1856, watching American scientist Eunice Foote demonstrate how carbon dioxide trapped heat from the sun—a discovery that would take more than a century to fully appreciate. The story of climate change awareness is one of humanity's most consequential journeys, filled with brilliant scientific insights, powerful resistance from vested interests, and the gradual awakening of global consciousness to an existential threat. This historical journey reveals three critical tensions that continue to shape our world: the gap between scientific knowledge and public understanding, the conflict between short-term economic interests and long-term planetary health, and the profound inequalities in who causes climate change versus who suffers its worst effects. Whether you're a student of environmental history, a climate advocate seeking context for today's movements, or simply someone trying to understand how we arrived at our current climate emergency, this exploration of how climate awareness evolved from obscure scientific theory to global movement offers essential perspective on humanity's greatest challenge.

Chapter 1: Early Climate Science: Foundations of Understanding (1850-1980)

The foundations of climate science were laid in the mid-19th century, far earlier than most people realize. In 1856, American scientist Eunice Foote conducted simple experiments showing that carbon dioxide could trap heat from the sun. Three years later, Irish physicist John Tyndall expanded on this work, demonstrating how certain atmospheric gases created what we now call the greenhouse effect. These pioneering scientists had discovered the basic mechanism behind climate change, though neither imagined human activities could significantly alter the planet's atmosphere. The early 20th century brought the first warnings about fossil fuels and climate. In 1896, Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius calculated that doubling atmospheric carbon dioxide would raise global temperatures by 5-6°C—remarkably close to modern estimates. However, most scientists believed the oceans would absorb excess carbon dioxide, preventing significant warming. This assumption delayed serious concern about climate change for decades. It wasn't until the 1950s that scientific instruments improved enough to challenge this view, when Charles David Keeling began precise measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide at Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, revealing its steady increase in what became known as the "Keeling Curve." The 1960s and 1970s saw crucial advances as computing power enabled the first climate models. Scientists like Syukuro Manabe at Princeton developed computer simulations showing that doubling carbon dioxide would indeed warm the planet significantly. Meanwhile, research on ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica provided a historical record of Earth's climate, confirming the relationship between carbon dioxide levels and temperature. The scientific community began raising concerns, with reports to the U.S. government warning of potential sea-level rise, agricultural disruption, and extreme weather events. Perhaps most surprisingly, major fossil fuel companies conducted sophisticated climate research during this period. Internal documents later revealed that companies like Exxon employed scientists who accurately predicted the warming we're experiencing today. A 1979 report by Exxon scientist James Black warned executives that "present thinking holds that man has a time window of five to ten years before the need for hard decisions regarding changes in energy strategies might become critical." Rather than acting on this knowledge or warning the public, many of these companies would later fund climate denial campaigns. By 1979, scientific understanding had advanced enough for the U.S. National Academy of Sciences to issue a landmark report concluding that doubling atmospheric CO2 would likely lead to warming between 1.5-4.5°C—a range remarkably similar to current estimates. The following year, the World Climate Research Programme was established to coordinate international climate research. These developments reflected growing scientific consensus about human-caused climate change, though public awareness remained limited. The early history of climate science reveals a troubling pattern that would persist for decades: scientists provided clear warnings about the consequences of fossil fuel use long before climate impacts became widely visible. Had society heeded these early warnings, the transition away from fossil fuels could have been gradual and less disruptive. Instead, economic and political forces resisted change, setting the stage for the more severe climate disruption and rushed transition we face today.

Chapter 2: Rising Awareness and First Warnings (1980-1997)

The 1980s marked the transition of climate change from an academic concern to a public issue. The decade began with the publication of the Charney Report, which confirmed that "a wait-and-see policy may mean waiting until it is too late." By 1985, scientists gathered at the Villach Conference in Austria issued a stark warning that greenhouse gases would "cause a rise of global mean temperature which is greater than any in man's history." These scientific assessments laid the groundwork for broader awareness, but it was the scorching summer of 1988 that truly brought climate change into public consciousness. June 23, 1988, stands as a pivotal moment in climate history. On that sweltering day in Washington D.C., NASA scientist James Hansen testified before Congress, declaring with "99% confidence" that global warming was underway and human-caused. His testimony made front-page headlines across America and introduced millions to the concept of global warming. That same year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established to provide policymakers with regular scientific assessments—an unprecedented international effort to bridge science and policy on a global scale. The early 1990s saw the first major political response to climate concerns. The 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro produced the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), signed by 154 nations. This landmark treaty acknowledged the problem and established the principle that developed nations should take the lead in emissions reductions, recognizing their historical responsibility. While the convention contained no binding targets, it created the framework for future climate negotiations and signaled growing international recognition of the issue. Media coverage of climate change increased significantly during this period, though often with problematic framing. News outlets frequently presented climate change as a controversial theory rather than established science, giving equal weight to mainstream scientists and industry-funded skeptics. This "false balance" reporting created public confusion about the level of scientific consensus. Meanwhile, extreme weather events like Hurricane Andrew in 1992 and the 1993 Mississippi River floods began raising questions about climate connections, though scientists remained cautious about attributing specific events to climate change. The fossil fuel industry recognized the existential threat that climate action posed to their business model and began orchestrating a sophisticated campaign to undermine public confidence in climate science. In 1989, major oil, gas, and auto companies formed the Global Climate Coalition to oppose greenhouse gas regulations. Internal documents later revealed that many member companies privately accepted climate science while publicly promoting doubt. This campaign borrowed tactics from the tobacco industry, manufacturing uncertainty by amplifying minor scientific disagreements and promoting fringe skeptics to create the illusion of significant scientific debate. By 1997, international negotiations had produced the Kyoto Protocol, which established legally binding emissions reduction targets for developed nations. This represented the first serious attempt to address climate change through coordinated global action. However, the agreement had significant limitations—most notably the refusal of the United States to ratify it and the exemption of major developing economies like China and India from binding targets. These shortcomings reflected the fundamental tensions that would continue to plague climate politics: between historical responsibility and current emissions, between economic growth and environmental protection, and between national sovereignty and global cooperation.

Chapter 3: Corporate Resistance and Political Inaction (1997-2009)

The period following the Kyoto Protocol's adoption in 1997 revealed the enormous power of corporate interests to obstruct climate action. Despite the scientific consensus strengthening with each passing year, a sophisticated denial machine went into overdrive. The fossil fuel industry, led by companies like ExxonMobil, funded a network of think tanks, pseudo-scientific organizations, and front groups dedicated to manufacturing doubt about climate science. Between 1998 and 2005, ExxonMobil alone spent an estimated $16 million funding organizations that promoted climate denial, despite their own scientists having confirmed the reality of human-caused warming decades earlier. This campaign of denial proved remarkably effective in the United States, where climate change became increasingly polarized along political lines. The election of George W. Bush in 2000 marked a significant setback for climate policy, as his administration formally withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in 2001. Administration officials edited scientific reports to downplay climate concerns, while industry representatives were appointed to key environmental positions. This period saw the emergence of what historians now call "the lost decade" for climate action—a critical window when emissions reductions could have been implemented gradually, but political will was deliberately undermined. Meanwhile, global emissions continued their relentless rise. Between 1997 and 2008, annual carbon dioxide emissions increased by approximately 30%, with much of this growth coming from rapidly industrializing economies like China and India. The atmospheric concentration of CO2 surpassed 380 parts per million—higher than at any point in the previous 800,000 years. This growth in emissions occurred despite the Kyoto Protocol coming into force in 2005, highlighting the limitations of an agreement that covered only a portion of global emissions and lacked strong enforcement mechanisms. The scientific warnings grew increasingly urgent during this period. The IPCC's Third Assessment Report in 2001 stated that "there is new and stronger evidence that most of the warming observed over the last 50 years is attributable to human activities." By the Fourth Assessment Report in 2007, the language had strengthened further, declaring warming "unequivocal" and human causation "very likely" (greater than 90% certainty). These reports detailed accelerating ice loss in Greenland and Antarctica, intensifying extreme weather events, and rising sea levels—all occurring faster than earlier models had predicted. Public awareness began shifting as climate impacts became more visible. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 devastated New Orleans and sparked discussions about climate change and vulnerability. Al Gore's documentary "An Inconvenient Truth" reached millions in 2006, winning an Academy Award and raising public consciousness. By 2007, climate concern had risen enough that Time magazine named climate change as the top environmental story of the year. These developments suggested a potential turning point in public engagement with the issue. The period ended with a mix of hope and disappointment. The 2008 election of Barack Obama in the U.S. promised a new approach to climate policy, while the 2009 Copenhagen Climate Conference was widely anticipated as a moment for transformative action. However, Copenhagen ended in disappointment, producing only a non-binding accord rather than a comprehensive treaty. This failure reflected the continuing power of fossil fuel interests, the deep divisions between developed and developing nations, and the challenge of addressing a long-term, global problem through traditional political mechanisms designed for short-term, national interests.

Chapter 4: Extreme Weather and Public Perception (2010-2018)

The period from 2010 to 2018 was marked by a dramatic increase in extreme weather events that began shifting public perception of climate change from an abstract future threat to a present reality. The Russian heat wave of 2010 killed an estimated 55,000 people, while Pakistan experienced catastrophic flooding that affected 20 million. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy caused $65 billion in damages and brought climate change to the doorstep of Wall Street. The California drought from 2012-2016 was the worst in 1,200 years, while 2017 saw Hurricane Harvey dump more than 60 inches of rain on Houston—the wettest tropical cyclone in U.S. history. These events made climate impacts visceral and immediate for millions of people. Scientific attribution studies advanced significantly during this period, allowing researchers to quantify climate change's role in specific extreme events. A landmark 2004 study had established the methodology, but by the 2010s, scientists could rapidly analyze major weather events. Studies found that climate change had made the 2010 Russian heat wave 5 times more likely, the 2013 Australian heat wave 5 times more likely, and the rainfall from Hurricane Harvey approximately 3 times more intense. This emerging "attribution science" transformed public discourse by connecting abstract climate statistics to specific disasters that dominated news headlines. Media coverage evolved substantially, with major outlets increasingly abandoning "false balance" reporting that gave equal weight to climate scientists and industry-funded skeptics. By 2018, mainstream news organizations routinely connected extreme weather events to climate change, with coverage of hurricanes, wildfires, and heat waves frequently including climate context. Social media also played a growing role in climate communication, allowing scientists to speak directly to the public and enabling the rapid spread of dramatic images from climate-fueled disasters. These shifts in media framing helped align public perception more closely with scientific understanding. Despite growing public awareness, political polarization on climate issues intensified in many countries. In the United States, the gap between Democratic and Republican voters' climate concerns widened significantly. The election of Donald Trump in 2016, who had called climate change a "Chinese hoax," led to a systematic dismantling of climate policies and withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. Similar patterns emerged in Australia, Brazil, and other nations where fossil fuel interests maintained strong political influence. This polarization created a paradoxical situation where public concern about climate was rising while political action in many countries was regressing. The financial sector began taking climate risks more seriously during this period. In 2015, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney warned about the economic threats of climate change, including potential "stranded assets" in the fossil fuel industry. Insurance companies, facing mounting losses from climate-related disasters, became vocal advocates for climate action. By 2018, over 500 organizations with assets exceeding $100 trillion had endorsed the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, signaling a major shift in how financial markets viewed climate risk. These developments suggested that economic forces might drive climate action even when political will was lacking. By the end of this period, public perception had shifted significantly in most countries. Polling showed majorities in most nations now viewed climate change as a major threat requiring immediate action. The concept of "climate emergency" began entering mainstream discourse, reflecting growing recognition of the crisis. However, this increased awareness had not yet translated into political action commensurate with the scale of the problem. The gap between what science indicated was necessary—rapid, systemic transformation of energy, transportation, and agricultural systems—and what political systems were delivering remained dangerously wide, setting the stage for more confrontational forms of climate activism in the years to come.

Chapter 5: Youth Movements and Climate Emergency (2019-Present)

The contemporary climate movement has been transformed by the unprecedented mobilization of young people demanding immediate action. In August 2018, 15-year-old Greta Thunberg began her solitary school strike outside the Swedish parliament, holding a sign that read "School Strike for Climate." What began as one teenager's protest quickly evolved into a global movement. By September 2019, over 7.6 million people participated in global climate strikes across 185 countries—the largest climate mobilization in history. The Fridays for Future movement fundamentally shifted climate activism by centering young voices and framing climate inaction as an intergenerational injustice. This youth movement coincided with the emergence of more confrontational climate activism. Extinction Rebellion, founded in the UK in 2018, employed civil disobedience tactics to demand that governments declare a climate emergency and achieve net-zero emissions by 2025. Their dramatic actions—occupying bridges in London, disrupting financial districts, and getting arrested in large numbers—generated significant media attention and helped normalize the concept of climate emergency. Meanwhile, the Sunrise Movement in the United States pushed for a Green New Deal, connecting climate action with job creation and social justice. These movements shared a rejection of incremental approaches and a demand for system-wide transformation. The COVID-19 pandemic beginning in 2020 dramatically altered the landscape of climate politics. Initial lockdowns caused unprecedented drops in emissions and air pollution, providing a glimpse of what rapid decarbonization might look like. Climate activists quickly drew parallels between the pandemic and climate emergency responses, noting that governments could mobilize trillions of dollars when faced with an immediate crisis. However, despite early rhetoric about "building back better," most COVID recovery spending failed to advance climate goals, with only about 10% of funds directed toward green initiatives in most major economies. Scientific warnings reached new levels of urgency during this period. The IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report, released in 2021-2022, declared human influence on the climate system "unequivocal" and warned that without immediate, deep emissions reductions, limiting warming to 1.5°C would be "beyond reach." Scientists also identified multiple climate tipping points that could be triggered between 1.5°C and 2°C of warming, including the collapse of major ice sheets and dieback of the Amazon rainforest. These warnings lent scientific credibility to activists' emergency framing and highlighted the closing window for effective action. Corporate climate commitments proliferated, with over 1,500 companies setting "net zero" targets by 2022. However, scrutiny of these pledges revealed widespread greenwashing, with many relying on problematic carbon offsets or setting distant deadlines without near-term action plans. Climate activists increasingly targeted financial institutions, arguing that banks and investors enabling fossil fuel expansion were undermining their own climate commitments. Campaigns against specific projects like the Keystone XL pipeline achieved notable victories, demonstrating the growing political and economic risks of fossil fuel infrastructure. The most recent period has seen climate politics become increasingly polarized between those demanding system-wide transformation and those defending the status quo. Youth activists continue to challenge the moral authority of leaders who fail to act, while Indigenous communities and Global South nations increasingly frame climate inaction as a form of neocolonialism. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 created new energy security concerns, simultaneously accelerating renewable energy transitions in some regions while temporarily increasing fossil fuel production in others. As extreme weather events continue to intensify—from devastating floods in Pakistan to record-breaking heat waves across Europe and China—the gap between scientific urgency and political action remains the central tension in contemporary climate politics.

Chapter 6: Indigenous Knowledge and Frontline Communities

Indigenous peoples have been at the forefront of climate activism, bringing unique perspectives shaped by millennia of sustainable relationships with the land. Comprising less than 5% of the world's population, Indigenous communities protect approximately 80% of Earth's remaining biodiversity within their territories. This is no coincidence—many Indigenous cultures maintain traditional ecological knowledge systems that view humans as integral parts of natural systems rather than separate from them. These worldviews often emphasize responsibilities to future generations and non-human species, providing philosophical frameworks that align naturally with sustainable practices. The Arctic has become an epicenter of Indigenous climate activism, as it warms at more than twice the global average rate. Inuit communities across Alaska, Canada, and Greenland have documented thinning sea ice, shifting wildlife patterns, and increasingly unpredictable weather that threatens traditional hunting and travel routes. Sheila Watt-Cloutier, an Inuit leader from Canada, pioneered the framing of climate change as a human rights issue, arguing before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights that warming threatens Inuit cultural survival. Her work helped establish the connection between climate change and cultural rights that has become central to Indigenous climate advocacy. In tropical regions, Indigenous peoples have been on the front lines of defending forests that serve as crucial carbon sinks. The Amazon rainforest, which stores approximately 123 billion tons of carbon, has been protected largely through Indigenous resistance to deforestation. Studies show that Indigenous territories in the Amazon have deforestation rates 50-80% lower than surrounding areas, demonstrating the effectiveness of Indigenous stewardship. However, these land defenders face escalating violence—over 200 environmental activists were killed globally in 2019 alone, with Indigenous people representing a disproportionate number of victims. Indigenous climate activism has increasingly focused on challenging extractive projects that threaten both local environments and global climate stability. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016-2017 became a watershed moment, bringing together over 200 Indigenous nations in the largest Native American gathering in a century. Similar Indigenous-led movements have opposed oil extraction in the Ecuadorian Amazon, coal mining in Australia, and pipeline projects across Canada. These struggles connect immediate threats to sacred lands with broader climate implications. Small island nations, many with Indigenous populations, have been powerful moral voices in international climate negotiations. Countries like Tuvalu, Kiribati, and the Marshall Islands face existential threats from rising seas despite contributing minimally to emissions. Former Maldivian President Mohamed Nasheed captured this injustice when he stated: "We are not prepared to die. We are not going to become the first victims of the climate crisis." These nations formed the Climate Vulnerable Forum to advocate for limiting warming to 1.5°C—a threshold critical for their survival. Their representatives have consistently emphasized that climate change is not merely an environmental issue but a matter of national survival. Despite their crucial role in climate protection, Indigenous peoples have historically been marginalized in formal climate governance. The Paris Agreement marked a turning point by acknowledging the importance of Indigenous knowledge, though many activists argue implementation remains inadequate. Indigenous groups continue to push for full recognition of their rights in climate policies, including free, prior, and informed consent for projects affecting their territories. As climate impacts intensify, the value of Indigenous knowledge systems—which have enabled adaptation to environmental changes for thousands of years—becomes increasingly apparent, offering vital wisdom for navigating the unprecedented challenges ahead.

Chapter 7: Climate Justice: Reframing the Global Challenge

Climate justice has emerged as a powerful framework that fundamentally reorients how we understand the climate crisis. Rather than viewing climate change as merely an environmental or technical problem, the justice perspective centers on the profound inequalities in who causes climate change versus who suffers its worst effects. This approach recognizes that the wealthiest 10% of the global population is responsible for nearly half of lifestyle consumption emissions, while the poorest 50% contributes just 10%. Yet those with the smallest carbon footprints—communities in low-lying islands, drought-prone regions of Africa, and flood-vulnerable Asian deltas—face the most severe climate impacts with the fewest resources to adapt. The concept of "climate debt" forms a cornerstone of climate justice thinking. This perspective holds that wealthy nations, having used more than their fair share of the atmospheric commons, owe compensation to those facing climate impacts. Historical emissions matter enormously—the United States and European countries have contributed approximately 60% of the cumulative carbon emissions since the Industrial Revolution, creating prosperity for themselves while imposing climate costs globally. Climate justice advocates argue that this historical responsibility should be reflected in how emissions reductions and climate finance are distributed, with wealthy nations achieving net-zero emissions far sooner than developing countries. Within countries, climate impacts and policies often reflect and reinforce existing social inequalities. In the United States, studies show that communities of color are exposed to 38% more polluted air than white communities and are more vulnerable to extreme heat due to historical redlining practices that left their neighborhoods with fewer trees and parks. Similar patterns exist globally, with marginalized communities typically facing greater exposure to climate hazards and having fewer resources to adapt. Climate justice requires that these communities not only be protected from disproportionate harm but also benefit first from climate solutions like clean energy, green spaces, and sustainable transportation. The concept of a "just transition" has become central to climate justice movements, particularly in regions dependent on fossil fuel industries. This approach recognizes that workers and communities tied to high-carbon sectors need support, training, and opportunities in the clean economy. Without deliberate planning, rapid decarbonization could leave behind coal miners in Appalachia, oil workers in Alberta, or mining communities in South Africa. Just transition frameworks emphasize that climate policies must create pathways to good jobs, revitalize affected communities, and ensure that the costs of transition don't fall on those already disadvantaged. Indigenous perspectives have profoundly shaped climate justice thinking. Many Indigenous frameworks emphasize reciprocity with nature rather than dominion over it, intergenerational responsibility, and the interconnectedness of all living beings. These worldviews challenge the extractive logic that has driven both colonialism and climate change. Indigenous communities have also pioneered legal strategies that recognize the rights of nature, as seen in Ecuador's constitution and New Zealand's granting of legal personhood to the Whanganui River. These approaches offer alternatives to economic systems that treat nature merely as resources to be exploited. The climate justice movement has transformed climate politics by connecting environmental concerns with broader struggles for social and economic justice. By framing climate action as a matter of human rights, racial equity, and decolonization, justice advocates have built broader coalitions and challenged narrow technical approaches. This reframing has particular resonance with young people, who increasingly see climate justice as inseparable from other social movements. As climate impacts intensify and the window for action narrows, the justice perspective offers not only a moral compass but also a strategic framework for building the political power necessary to drive transformative change.

Summary

The journey from scientific discovery to global movement reveals a profound disconnect between knowledge and action that defines the climate crisis. Since the 1850s, when scientists first identified the greenhouse effect, our understanding of climate change has steadily evolved from theoretical concern to empirical certainty. Yet this growing scientific consensus has been met with decades of deliberate obfuscation, political inertia, and systemic resistance. The central tension throughout this history has been between the exponential nature of climate change—with its tipping points, feedback loops, and irreversible impacts—and the incremental, compromise-oriented nature of human institutions. This fundamental mismatch explains why, despite over thirty years of international climate negotiations, global emissions continued rising until the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily interrupted the trend. Looking forward, this history offers both cautionary lessons and reasons for hope. First, technical solutions alone are insufficient without addressing underlying power dynamics and economic systems that drive emissions. The fossil fuel industry's decades-long campaign to delay action demonstrates that climate change is fundamentally a political problem requiring political solutions. Second, effective climate action must center justice and equity—both because frontline communities have contributed least to the problem while suffering its worst effects, and because broad-based movements are necessary to overcome entrenched resistance. Finally, the recent surge in youth activism shows that rapid normative shifts are possible when moral clarity meets collective action. By connecting climate to existing values like intergenerational responsibility, community resilience, and fairness, activists have begun transforming climate from an abstract scientific issue into a tangible moral imperative that demands immediate response.

Best Quote

“The transformation we need in order to stay below 1.5 C or even 2 C of warming may not be politically possible today. But we are the ones who determine what will be politically possible tomorrow.” ― Greta Thunberg, The Climate Book: The Facts and the Solutions

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights the book's ability to synthesize complex topics into accessible, bite-sized essays, totaling 100, which balance nuance and readability. It also mentions the inclusion of the reviewer's favorite authors, enhancing its appeal. Weaknesses: Not explicitly mentioned. Overall Sentiment: Enthusiastic Key Takeaway: The book effectively challenges the reader's understanding of capitalism's inherent logic, contrasting it with personal philosophies of preparedness and resilience. It provokes a deep reflection on the intersection of personal beliefs and broader socio-economic systems.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.