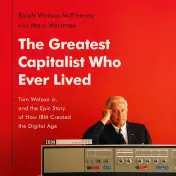

The Greatest Capitalist Who Ever Lived

Tom Watson Jr. and the Epic Story of How IBM Created the Digital Age

Categories

Business, Nonfiction, Finance, Biography, History, Technology, Audiobook

Content Type

Book

Binding

Audiobook

Year

2023

Publisher

PublicAffairs

Language

English

ISBN13

9781549134883

File Download

PDF | EPUB

The Greatest Capitalist Who Ever Lived Plot Summary

Introduction

In the pantheon of American business leaders, few figures loom as large as Thomas Watson Jr. Taking the reins of IBM from his legendary father in the 1950s, Watson transformed a successful tabulating machine company into the dominant force in the emerging computer industry, forever changing the technological landscape of the 20th century. His decision to bet IBM's entire future on the revolutionary System/360 computer family represented one of the most audacious gambles in business history—a $5 billion wager that nearly bankrupted the company before ultimately establishing IBM's dominance for decades to come. Watson's journey from troubled, insecure son to visionary CEO embodies the classic American narrative of personal reinvention. Through his leadership, IBM became not just the world's most valuable company but also a model for corporate culture, design excellence, and social responsibility. His story reveals profound insights about navigating technological disruption, managing the complex dynamics of family business succession, and balancing commercial success with ethical leadership. Beyond his business achievements, Watson's transformation from corporate titan to diplomat in his later years demonstrates how leadership principles can transcend the boardroom to address global challenges.

Chapter 1: Growing in a Legend's Shadow: Early Struggles and Insecurities

Thomas Watson Jr. was born in 1914 into a life of both privilege and extraordinary pressure. As the eldest son of Thomas J. Watson Sr., the legendary founder and leader of IBM, young Tom grew up in the shadow of a corporate titan whose name had become synonymous with business success. The elder Watson had transformed a struggling conglomerate into a thriving business machines company through sheer force of will, marketing genius, and an almost religious devotion to his corporate family. For the son, this created an overwhelming burden of expectation that would shape his early life and career. Unlike his disciplined, focused father, young Tom struggled academically, battling what would later be recognized as dyslexia. School was a series of failures and disappointments, with Tom bouncing between institutions as his poor grades and mischievous behavior led to one expulsion after another. He earned the nickname "Terrible Tommy" for his pranks and rebellious attitude. At one school, he poured skunk oil into the heating system, forcing an evacuation. His father's response was telling: "I don't need to discipline you! The world will discipline you, you little skunk!" These academic struggles only deepened his sense of inadequacy when compared to his father's towering achievements. The Watson household operated like an extension of IBM itself, with Thomas Sr. as the unquestioned authority. Family dinners often featured lectures on business principles and proper conduct. Even at home, the elder Watson rarely shed his formal attire or his commanding presence. For Tom Jr., this created a complex relationship with his father—one marked by deep admiration but also resentment and rebellion. "I really wanted to beat him but also make him proud of me," he would later confess. This ambivalence would fuel both his drive to succeed and his periodic bouts of depression throughout his life. Despite these struggles, Tom found one area where he excelled: flying. When he took his first flying lessons during college at Brown University, he discovered a natural talent and passion that gave him a sense of independence. In the cockpit, free from his father's shadow, Tom found the confidence that eluded him elsewhere. "This was something I was good at... instantly good," he recalled. Flying became his escape and would later prove crucial to his personal transformation, particularly during his military service in World War II. By the time Tom graduated from Brown in 1937 (after six years and three schools), he reluctantly joined IBM as a salesman. His early career mirrored his educational struggles—he made sales easily, but primarily because customers wanted to curry favor with his father. This hollow success only deepened his sense of unworthiness. "The better I got at selling," he recalled, "the less I worked." He seemed destined to remain the disappointing son of a business legend, until world events offered an unexpected opportunity for reinvention that would ultimately change not just his life but the future of computing.

Chapter 2: Finding Purpose Through War: Military Service and Self-Discovery

When World War II erupted, Thomas Watson Jr. saw his chance for escape and self-discovery. In 1940, at age 26, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps, eager to put his flying skills to use and to build an identity separate from IBM and his father. This decision would prove transformative, setting him on a path toward becoming one of the most influential business leaders of the twentieth century. The military provided Watson with structure, purpose, and most importantly, the opportunity to prove himself on his own merits. In 1942, he was assigned as aide-de-camp to Major General Follett Bradley, who was leading a critical mission to establish an air supply route through Siberia to deliver American aircraft to the Soviet Union. This assignment would become what Watson later called "the most important of my life." Flying a B-24 bomber across some of the world's most treacherous terrain, Watson faced life-threatening challenges that tested his courage and leadership abilities. During one harrowing flight over Siberia, two engines failed while ice built up on the wings. As the plane lost altitude in the arctic darkness, Watson helped navigate the crippled aircraft back to safety. General Bradley noted in his diary that "with most pilots, even good ones, this flight would have ended in disaster." This and other near-death experiences gave Watson a confidence he had never known. For the first time, he was succeeding without his father's help or name, earning respect based solely on his own abilities and character. Beyond the technical aspects of flying, Watson discovered his talent for logistics and operations. He excelled at planning complex missions, coordinating supplies, and solving problems under pressure. When tasked with overseeing preparations for the epic ten-day flight to Moscow, Watson demonstrated exceptional organizational skills. "This was the biggest job I'd ever undertaken," he later wrote. His ability to focus on what was important and communicate it effectively to others revealed leadership qualities he hadn't known he possessed. Perhaps most significantly, Watson learned crucial lessons about leadership from General Bradley. He observed how the general built morale, motivated his crew, and made decisions under pressure. "To be a good leader," Watson realized, "I had to strike a delicate balance" between pushing people hard and maintaining their loyalty and enthusiasm. When his crew once confronted him about his demanding management style, Watson took the criticism to heart and adjusted his approach, learning that "petty criticism is not useful if people are doing a reasonably good job." By the time Watson returned to civilian life in 1946 at age thirty-two, he was a transformed man. The insecure, rebellious youth had become a decorated lieutenant colonel with proven leadership abilities and newfound self-confidence. When General Bradley asked about his future plans and Watson mentioned becoming a commercial pilot, Bradley responded with surprise: "I always thought you'd go back and run the IBM company." When Watson asked if Bradley thought he could do it, the general's simple "Of course" was a validation that changed Watson's trajectory. He returned to IBM with a new sense of purpose and the confidence to challenge his father's vision for the company's future.

Chapter 3: Taking the Helm: Battling for IBM's Technological Future

When Thomas Watson Jr. returned to IBM in January 1946, he brought with him a new sense of purpose and confidence. However, he quickly found that the company his father had built remained firmly under the elder Watson's control. At seventy-two, Thomas Watson Sr. still dominated every aspect of IBM, running it as a personal fiefdom where subordinates accepted his word without question. The corporate culture centered on him had succeeded for more than thirty years, but the younger Watson immediately recognized it would need to change to meet postwar challenges. The clash between father and son was inevitable and often explosive. Tom Jr. bristled at what he called the "atmosphere of adulation" surrounding his father: "He had people hanging on his every word as if he were the Messiah." He found IBM's management structure woefully inadequate for a company that had doubled in size during the war. With thirty-eight managers reporting directly to the CEO and no formal organization chart, important decisions were delayed or never made. Tom Jr. craved order and clear lines of authority, much like he had experienced in the military. Their battles over IBM's direction became legendary within the company. "Our fights were savage, primal, and unstoppable," Watson recalled. They often ended with one or the other storming off in rage or tears. Once, after a particularly heated exchange, Tom Jr. rushed from his father's office and flung himself down sobbing on a shocked manager's couch. Their shouting matches echoed down the hallways of IBM headquarters and occasionally spilled into public view. After one explosive argument at the Metropolitan Club, the elder Watson returned to his office and drafted a letter firing his son, though he never sent it. The central point of contention became IBM's approach to the emerging field of electronics. In 1946, Tom Jr. witnessed a demonstration of an electronic calculator that could process information far faster than IBM's mechanical tabulators. He immediately grasped its significance: "Dad, we should put this thing on the market!" But his father remained skeptical, believing that punch-card machines would continue to dominate business data processing. "The electronic computer would have no impact on the way IBM did business," the elder Watson insisted, "because to him punch-card machines and giant computers belonged in totally separate realms." Despite his father's resistance, Tom Jr. began pushing IBM toward electronics. He convinced his father to hire more electrical engineers and increase research spending. When competitors like Remington Rand's UNIVAC began making inroads into IBM's traditional markets, Tom Jr. sounded the alarm. After learning that UNIVAC had displaced IBM tabulators at the Census Bureau, he felt "terrified" by the threat to IBM's core business. Even his father was shaken when he heard this news, as the Census Bureau had been IBM's client since the company's origins. By 1952, his father promoted him to president—tantamount to naming him successor. When the elder Watson died in 1956, Tom Jr. finally had the authority to fully implement his vision. He immediately reorganized the company, creating a modern management structure and accelerating IBM's transition to electronic computing. Under his leadership, IBM would not merely adapt to the computer revolution—it would come to dominate it, transforming from a business machine company into the world's premier technology corporation.

Chapter 4: The System/360 Gamble: Betting the Company on a Vision

By the early 1960s, Thomas Watson Jr. had successfully steered IBM into the computer business, but the company faced a critical strategic dilemma. IBM had developed multiple incompatible computer lines, each designed for specific purposes. Scientific computers couldn't run business applications and vice versa. When customers wanted to upgrade to more powerful systems, they had to replace everything—hardware, software, and peripherals—and retrain their staff. Meanwhile, competitors were beginning to exploit this weakness by offering machines that could run IBM programs, threatening to steal IBM's customers. In 1961, Watson assembled a task force called the SPREAD Committee to develop a solution. After intense deliberation, they proposed something revolutionary: a family of compatible computers spanning from small to large, all using the same architecture and able to run the same software. This "New Product Line" would make all of IBM's existing computers obsolete but would offer customers unprecedented flexibility and growth potential. The engineering challenges were enormous—no one had ever built such a system before. It would require new microelectronics, new manufacturing facilities, and the most complex software ever written. When the committee presented their findings in January 1962, many executives thought the plan was too ambitious. It would cost an estimated $675 million—nearly three times IBM's annual earnings—and tie up virtually all the company's resources in a single project. After listening to the presentation, Watson simply turned to his team and said, "Do it." With those two words, he launched what would become the largest privately financed commercial project in history, eventually costing over $5 billion (equivalent to about $43 billion today). The System/360, as it was eventually named (for the 360 degrees of a compass, indicating it could handle any computing task), was announced on April 7, 1964, in what Watson called "the most important product announcement in the company's history." But behind the scenes, IBM was in crisis. The machines displayed at the announcement were mostly hollow mockups; the software was months, even years, from being ready; and the factories to manufacture the revolutionary components were still under construction. As delays mounted and costs spiraled out of control, IBM's cash reserves dwindled until the company was just weeks away from being unable to meet its payroll. The crisis forced Watson to make painful decisions. In a move that would haunt him personally, he effectively fired his brother, Arthur "Dick" Watson, who had been charged with resolving production problems. The brothers had long maintained a complex relationship, with Dick heading IBM's World Trade Corporation while Tom ran domestic operations. Their father had divided the company between them in a King Lear-like fashion, hoping they would lead together. But when the System/360 crisis threatened IBM's survival, Tom chose the company over family harmony. Despite the turmoil, Watson's bet ultimately paid off spectacularly. The System/360 revolutionized computing, establishing a standard architecture that would dominate the industry for decades. It made possible numerous technologies we take for granted today: automated banking, credit card processing, airline reservation systems, and the foundations of database management. By 1970, IBM's revenue had more than doubled to $7.5 billion, and its workforce had grown from 150,000 to 270,000. Watson had successfully navigated the most perilous transition in the company's history, betting everything on his vision of computing's future—and winning.

Chapter 5: Leadership Philosophy: Building the Modern IBM Culture

Thomas Watson Jr.'s leadership philosophy represented both a continuation and a transformation of the culture his father had established. While he maintained his father's emphasis on customer service, employee loyalty, and corporate values, he fundamentally restructured how IBM operated, creating a more decentralized organization capable of thriving in the fast-paced technology industry. At the core of Watson's leadership approach was his belief in balancing innovation with discipline. "I could press to a point beyond where most people would press," he observed, "but short of where I became known as a troublemaker." This delicate balance allowed him to drive IBM forward aggressively while maintaining the organizational cohesion necessary for a global enterprise. Unlike his father, who kept all decision-making power centralized in his own hands, Tom Jr. created a management structure with clear lines of authority and responsibility, enabling faster responses to market changes. Watson articulated his management philosophy in a series of "Management Briefings" sent to IBM executives between 1958 and 1971. These concise memos covered topics ranging from customer service to business ethics. "IBM means service," he declared in one briefing, emphasizing that answering the telephone promptly (which he did himself) was as important as developing cutting-edge technology. In another, he insisted that "each employee must observe the highest standards of business integrity and avoid any activity which might tend to embarrass IBM or him." Perhaps his most significant leadership insight was recognizing that in a fast-changing industry, adaptability was essential. "The only sacred cow in an organization," he declared, "should be its philosophy of doing business." Everything else could and should change as technology and markets evolved. This principle guided IBM through multiple technological transitions, from punch cards to magnetic tape to integrated circuits, allowing the company to maintain its leadership position despite rapid technological change. Watson maintained his father's commitment to employee welfare but modernized it for the postwar era. He continued IBM's no-layoff policy, comprehensive benefits, and promotion from within, but added programs for continuing education and retraining that helped employees adapt to technological change. When other companies were still practicing racial discrimination, Watson insisted on equal opportunity in hiring and promotion. In 1953, he wrote to all IBM managers: "It is the policy of this organization to hire people who have the personality, talent and background necessary to fill a given job, regardless of race, color or creed." Watson's most enduring contribution to corporate culture was his belief that "good design is good business." In 1956, he hired Eliot Noyes, a Harvard-trained architect and industrial designer, to create a comprehensive corporate design program. Under Noyes's direction, IBM developed a distinctive visual identity that extended from its products to its buildings, graphics, and exhibitions. Watson brought in renowned designers like Paul Rand, who created IBM's iconic eight-bar logo, and architects like Eero Saarinen and Marcel Breuer to design IBM facilities worldwide. This emphasis on design excellence communicated IBM's values of precision, innovation, and quality, setting a standard that many other corporations would later emulate.

Chapter 6: Personal Demons: Managing Success Amid Inner Turmoil

Behind Thomas Watson Jr.'s extraordinary business success lay a complex, troubled man who battled personal demons throughout his life. From his youth, Watson suffered from debilitating bouts of depression that would leave him bedridden for weeks at a time. "All my willpower would evaporate," he recalled. "I didn't want to get out of bed. I had to be urged to eat; I had to be urged to take a bath." These episodes, which today would be diagnosed as major depression, first struck when he was thirteen and continued to plague him periodically, especially during the Christmas season. Watson's emotional struggles were compounded by undiagnosed dyslexia that made reading difficult throughout his life. "Words on a page seemed to swim around whenever I tried to read," he explained. This learning disability contributed to his poor academic performance and feelings of inadequacy, particularly painful for the son of a legendary father. Even as CEO of one of the world's most successful corporations, Watson remained insecure about his intellectual abilities, once admitting, "I never felt too sure of my intellectual depth." To cope with these insecurities and the immense pressure of running IBM, Watson developed a pattern of risk-taking behavior that bordered on recklessness. He flew airplanes in dangerous conditions, sailed through storms, raced cars at excessive speeds, and skied down treacherous slopes. "I was a dervish of activity, always eager to try something new, the more dangerous the better," his daughter Jeannette recalled. These activities provided not just an escape from business pressures but also a way to recapture the thrill of brushing against death that he had experienced during wartime flying. His marriage to Olive Cawley, a former model and actress whom he married hastily before shipping out for war service in 1941, weathered significant strains. While Olive provided emotional support that helped Watson manage his depression, his volatile temper, frequent absences, and extramarital affairs created tensions. When depression overwhelmed him, he would sometimes lock himself in the bathroom of their Greenwich mansion for days, refusing to come out. Olive's philosophy of "Laugh and the world laughs with you, cry and you cry alone" helped her navigate life with her emotionally unpredictable husband. The System/360 crisis of the mid-1960s took a particularly heavy toll on Watson's mental health. As IBM teetered on the brink of financial disaster, he later admitted, "I was close to a nervous breakdown." The strain of betting the company's future on an unproven technology while managing production delays, cost overruns, and internal conflicts pushed him to his limits. That he maintained his leadership through this period testifies to his remarkable resilience. Perhaps the most painful episode in Watson's personal life involved his brother Dick. When production problems with the System/360 threatened IBM's survival, Tom effectively fired Dick, who had been tasked with resolving manufacturing issues. This business decision fractured their relationship. Dick's subsequent alcoholism and early death at age 55 in 1974 left Tom with lasting guilt. "I think about Dick every day," he confessed years later. Despite these personal struggles, Watson managed to channel his inner turmoil into productive leadership, transforming both IBM and the entire computer industry while battling the demons that threatened to overwhelm him.

Chapter 7: Legacy: Architect of the Computer Age

Thomas Watson Jr.'s transformation of IBM from a tabulating machine company into the dominant force in computing represents one of the most significant business achievements of the 20th century. Under his leadership from 1956 to 1971, IBM's revenue grew from $892 million to nearly $8 billion, its workforce expanded from 72,500 to more than 270,000, and its market value increased to make it the most valuable company in the world. More importantly, Watson's vision and willingness to take enormous risks fundamentally shaped the development of the computer industry and the information age. The System/360, despite its troubled birth, became the most successful product launch in business history. By standardizing computer architecture and creating a family of compatible machines, Watson established the paradigm that would define mainframe computing for decades. The System/360's success forced competitors to build IBM-compatible systems, effectively making IBM's architecture the industry standard. This standardization accelerated the adoption of computers across all sectors of the economy and laid the groundwork for the information technology revolution that followed. Watson's impact extended far beyond technology. His "good design is good business" philosophy influenced corporate America's approach to design, architecture, and visual identity. His management innovations, including the decentralization of authority and the system of "contention management," provided a model for how large corporations could maintain agility and innovation despite their size. His progressive workplace policies and commitment to racial equality set standards that other companies would eventually follow. After suffering a heart attack in 1970, Watson stepped down as CEO in 1971, though he remained chairman until 1973. In retirement, he increasingly turned his attention to public service and international affairs. His interest in East-West relations, dating back to his wartime experiences in Moscow, led him to accept President Jimmy Carter's appointment as U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union in 1979. Though his tenure was cut short by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Watson remained committed to improving international understanding, establishing the Watson Institute for International Studies at Brown University to promote research on global security and cooperation. Throughout his later years, Watson pursued his passions with characteristic intensity. He sailed his yacht Palawan on epic voyages to remote corners of the globe, including the Arctic and South Pacific. He continued flying well into his seventies, piloting everything from helicopters to jets. These adventures reflected his lifelong need for challenge and his determination to live life on his own terms. Yet he also devoted significant time and resources to philanthropy, particularly at Brown University, which received the majority of his personal fortune. When Watson died on December 31, 1993, he left behind a legacy that extends far beyond IBM. His vision of computing as an essential tool for business and society has been vindicated by history. The principles he established—customer focus, respect for the individual, excellence in execution, and ethical business practices—remain relevant in today's rapidly evolving technological landscape. In bridging the gap between his father's mechanical age and our digital present, Watson helped create the modern world.

Summary

Thomas Watson Jr.'s life journey represents one of the most remarkable business transformations in history. Taking the reins from his legendary father, he navigated IBM from the mechanical tabulating era into the electronic computer age through sheer force of will, strategic vision, and calculated risk-taking. His greatest achievement—the System/360 family of compatible computers—represented the largest private business investment of its time and revolutionized how organizations implemented technology. Despite nearly bankrupting IBM in the process, this audacious gamble ultimately established IBM's dominance in computing for decades and made it the world's most valuable company. Watson's legacy extends beyond business success to encompass his pioneering approach to corporate culture and social responsibility. He established principles that still resonate today: that good design is good business, that companies should respect the dignity of every employee, and that business leaders have responsibilities beyond profit maximization. His later career in diplomacy and international affairs demonstrated his belief that business leaders should address broader societal challenges. For today's leaders, Watson offers a powerful example of how to balance innovation with execution, risk-taking with responsibility, and commercial success with ethical principles. His life reminds us that transformative leadership requires not just strategic brilliance but the courage to bet on a vision of the future that others cannot yet see.

Best Quote

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights the compelling narrative style of the biography, likening it to an interesting fiction story despite its factual basis. It emphasizes the influence of Thomas Watson Junior's grandmother on his and his father's success, and praises the detailed account of IBM's history provided by the author, Ralph.\nOverall Sentiment: Enthusiastic\nKey Takeaway: The biography of Thomas Watson Junior and his father, Thomas Watson Senior, is portrayed as an engaging and insightful read that offers a detailed account of IBM's history and the personal and professional journeys of its leaders. The review appreciates the role of family influence and resilience in their success, ultimately endorsing the book as a worthwhile read for those interested in the story of IBM and its leaders.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.