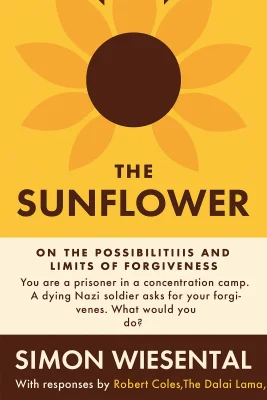

The Sunflower

On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness

Categories

Nonfiction, Philosophy, History, Memoir, Religion, Spirituality, School, Holocaust, World War II, Jewish

Content Type

Book

Binding

Paperback

Year

1997

Publisher

Schocken Books (NY)

Language

English

ASIN

0805210601

ISBN

0805210601

ISBN13

9780805210606

File Download

PDF | EPUB

The Sunflower Plot Summary

Introduction

In the heart of one of history's darkest chapters, a dying Nazi soldier seeks forgiveness from a Jewish concentration camp prisoner. This extraordinary moral confrontation frames one of the most profound ethical dilemmas of our time: what are the limits of forgiveness? Can anyone forgive crimes committed against others? The encounter described in these pages takes us beyond abstract philosophical questions into the raw reality of human suffering and the complex possibility of reconciliation. Through this deeply personal narrative, readers confront challenging questions that extend far beyond the Holocaust. What does it mean to truly repent? Can monsters become human again in their final moments? Do the victims of atrocities have an obligation to respond to their perpetrators' remorse? The narrative expands from this singular encounter to explore theological perspectives from multiple faith traditions, the nature of collective guilt, and how societies might move forward after devastating moral ruptures. Whether you are a student of history, ethics, religion, or simply someone grappling with the boundaries of human decency, this exploration offers no easy answers but illuminates the terrain of our most difficult moral questions.

Chapter 1: The Encounter: A Jewish Prisoner and a Dying SS Man

The story begins in Nazi-occupied Poland during the darkest days of World War II. Simon, a Jewish prisoner in a concentration camp, is unexpectedly summoned to the bedside of Karl, a dying SS officer in a military hospital. The encounter takes place around 1944-45, when the systematic destruction of European Jewry was in full operation. Simon finds himself facing a moral crisis that would haunt him for decades to come. In the sterile hospital room, Simon confronts a young man whose head is completely bandaged, with openings only for his mouth, nose, and ears. Karl, mortally wounded on the Russian front, reveals that he voluntarily joined the Hitler Youth as a teenager and later enlisted in the SS, despite coming from a Catholic family with a father who opposed the Nazi regime. His mother, however, offered little resistance to his decisions. Karl proceeds to confess his participation in the brutal murder of Jewish civilians, describing in excruciating detail how his unit herded Jewish families into a house, set it ablaze with grenades, and then shot anyone attempting to escape the flames. The dying Nazi describes his haunting memory of a particular Jewish family – a father carrying his child, whose eyes he shielded before jumping from the burning building, followed by the mother. This image has tormented Karl ever since. In his final hours, he seeks absolution, telling Simon: "I know that what I am asking is almost too much for you, but without your answer I cannot die in peace." The weight of this request is staggering – a Jewish prisoner being asked to grant forgiveness for crimes committed against other Jews, people who can no longer speak for themselves. Simon listens to this confession in stunned silence. Though he has every reason to hate this man, he finds himself caught between his natural human empathy for suffering and his obligation to honor the memory of countless murdered Jews. When Karl finishes his confession and extends his hand seeking forgiveness, Simon struggles with an impossible moral dilemma. Ultimately, Simon leaves the room without speaking, neither granting forgiveness nor explicitly refusing it. His silence becomes its own profound response – ambiguous, troubled, and deeply human. The encounter raises fundamental questions about the nature of guilt and forgiveness. Can one person forgive crimes committed against others? Does true repentance deserve mercy, regardless of the magnitude of the crime? Simon's struggle illuminates the impossible position of victims asked to shoulder the additional burden of absolving their perpetrators.

Chapter 2: The Moral Dilemma: Can One Forgive on Behalf of Others?

In the aftermath of his encounter with Karl, Simon finds himself deeply troubled by his response. Back at the camp, he shares his experience with fellow prisoners, seeking their perspectives on whether his silence was the right choice. This period of reflection, occurring while still under the shadow of imminent death in the concentration camp, represents a remarkable testament to the human capacity for moral contemplation even in the most dehumanizing circumstances. Simon's Jewish friends largely support his decision not to forgive. His friend Josek articulates a crucial principle that becomes central to the moral question: "You have suffered nothing because of him, and it follows that what he has done to other people you are in no position to forgive." This perspective echoes traditional Jewish teaching that only the direct victim of a wrong can grant forgiveness. Since the actual victims of Karl's atrocity were dead, killed by his own hand, no living person could offer absolution on their behalf. Arthur, another friend, frames the issue differently, saying: "A superman has asked a subhuman to do something which is superhuman. If you had forgiven him, you would never have forgiven yourself all your life." This powerful statement highlights the asymmetry of power even in Karl's deathbed vulnerability, and the impossible burden placed on Simon. However, a Polish Catholic prisoner named Bolek presents a contrasting view, suggesting that the dying man's genuine repentance deserved some response of mercy. The debate extends beyond theoretical ethics to deep questions about human identity and representation. Could Simon speak for the Jewish people? Would forgiving Karl diminish the horror of what happened to his victims? Would refusing forgiveness perpetuate cycles of hatred? The moral tension is heightened by Simon's recognition of Karl's humanity – not as an abstract monster but as someone shaped by his society and choices, who ultimately recognized the evil he had committed. This moral dilemma transcends the specific historical context to raise universal questions about reconciliation after atrocity. It forces us to consider the limits of human forgiveness, the rights of victims versus the needs of perpetrators, and whether some crimes are simply beyond the realm of what can be forgiven by human beings. Simon's inner struggle becomes a microcosm for how societies grapple with healing deep historical wounds.

Chapter 3: Theological Perspectives: Jewish and Christian Approaches to Forgiveness

The question of forgiveness after atrocity inevitably engages profound theological dimensions, revealing significant differences between Jewish and Christian approaches to repentance, atonement, and absolution. These divergent perspectives emerged clearly when Simon later shared his story with religious thinkers from various traditions. In the Jewish tradition, teshuvah (repentance) involves a multi-step process. One must acknowledge wrongdoing, express genuine remorse, make restitution when possible, and commit to never repeating the offense. Critically, when sins are committed against another person rather than against God alone, forgiveness must be sought directly from the wronged party. As Abraham Joshua Heschel articulates in his response to Simon's dilemma: "No one can forgive crimes committed against other people." The Jewish perspective generally holds that while God may forgive sins against divine law, humans can only forgive wrongs done directly to them – making forgiveness for murder fundamentally impossible since the victim cannot grant it. Christian perspectives often emphasize divine mercy and the universal call to forgiveness as exemplified by Jesus's words on the cross: "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do." Several Christian respondents suggest that withholding forgiveness from a genuinely repentant person contradicts core Christian teaching, regardless of the magnitude of their crime. The Catholic priest Edward Flannery writes: "It is a cardinal principle of Judeo-Christian ethics that forgiveness must always be granted to the sincerely repentant." However, this theological divide is not absolute. Some Christians recognize the complexity of forgiving on behalf of others, while some Jewish thinkers acknowledge the transformative power of repentance. Rabbi Harold Kushner suggests that true repentance comes when the perpetrator fundamentally changes who they are, making a clean break with their past self – though this does not automatically entitle them to forgiveness from others. Both traditions wrestle with the relationship between divine and human forgiveness. Can God forgive what humans cannot? Does divine mercy have limits? The theological tension becomes particularly acute in cases of mass atrocity, where traditional religious frameworks developed to address individual sins seem inadequate to comprehend systematic evil on an industrial scale. Some respondents even suggest that the Holocaust itself requires a theological reconsideration of God's role in human affairs. These theological reflections extend beyond abstract doctrines to practical questions about how societies heal. They raise profound questions about whether reconciliation requires forgiveness, how communities of faith should respond to perpetrators of grave evil, and what religious resources exist for addressing historical trauma that crosses generational lines.

Chapter 4: The Burden of Memory: Visiting Karl's Mother in Stuttgart

Years after the war ended, Simon makes a remarkable journey to Stuttgart to visit Karl's mother. This chapter of the story, taking place in the immediate post-war period around 1946, reveals another dimension of the moral complexity surrounding forgiveness and truth-telling. Having survived the camps against all odds, Simon now enters the bombed-out ruins of Germany, where he finds Karl's mother living in poverty amid the devastation. The elderly woman welcomes Simon into her modest apartment without knowing his true connection to her son. She proudly displays Karl's photograph, describing him as "a dear good boy" who was devoted to her. When she speaks of her husband, who died in a bombing after Karl's death, Simon learns that the father had indeed been a Social Democrat who opposed the Nazis. Karl's decision to join the Hitler Youth and later the SS had created a painful rift in the family, with the father essentially disowning his son while the mother remained loyal to both. Faced with this grieving woman who has already lost everything, Simon makes a momentous decision: he does not tell her the truth about her son's confession. Instead, he fabricates a story about merely receiving a message from Karl through a hospital train window. This merciful lie spares the mother from knowing the atrocities her son committed, allowing her to preserve her image of him as fundamentally good despite his Nazi affiliation. This encounter raises profound questions about truth, mercy, and the burden of knowledge. Simon reflects: "I knew that from time to time she would take in her arms her son's bundle, his last present, as if it were her son himself." His choice to withhold the truth can be seen as either an act of compassion or a betrayal of the victims whose memory demands honesty about what was done to them. The dilemma echoes larger societal questions about how Germany itself would confront or avoid its Nazi past. Simon's decision not to burden Karl's mother with the horrific truth parallels broader patterns of selective silence in post-war Europe. Many families maintained protective myths about what their fathers, sons, and husbands had done during the war. Yet Simon's mercy toward this individual woman stands in contrast to his unwavering commitment to hunting Nazi criminals and ensuring legal accountability for Holocaust perpetrators in his later life. This visit to Stuttgart illustrates how the ripples of moral complexity extend far beyond the original encounter. The burden of memory weighs not only on victims but also on perpetrators' families and communities. Simon's silence in this instance – unlike his silence at Karl's bedside – is a deliberate choice that acknowledges the limits of truth-telling when it can only cause pain without the possibility of justice or redemption.

Chapter 5: The Holocaust Legacy: Individual and Collective Responsibility

The decades following World War II have been marked by ongoing debates about the nature and extent of responsibility for the Holocaust. These conversations involve complex questions about individual guilt versus collective responsibility, and the obligations of subsequent generations who did not personally participate in the atrocities but inherit their legacy. At the individual level, the narrative of Karl reveals the inadequacy of reducing Nazi perpetrators to one-dimensional monsters. Karl was shaped by family dynamics, religious upbringing, peer pressure, political indoctrination, and ultimately his own choices. His journey from church altar boy to SS murderer illustrates how ordinary people can become participants in extraordinary evil through a series of incremental moral compromises. His death-bed repentance raises questions about whether last-minute contrition can meaningfully address crimes of such magnitude, especially when the perpetrator faces no consequences beyond his own conscience. The problem of collective responsibility emerges most clearly in Simon's interactions with Germans after the war. Karl's mother claims, "In this district we always lived with the Jews in a very peaceful fashion. We are not responsible for their fate." This common refrain – "we didn't know" or "we weren't personally involved" – represents a widespread evasion among Germans in the post-war period. Simon responds that while he rejects the notion of collective guilt, there is such a thing as national responsibility: "It is the duty of Germans to find out who was guilty. And the non-guilty must dissociate themselves publicly from the guilty." This distinction between guilt and responsibility became crucial to Germany's eventual path toward confronting its Nazi past. Legal guilt belongs to those who committed specific crimes, but responsibility extends to bystanders, beneficiaries, and later generations who inherit the obligation to ensure "never again." Hannah Arendt's concept of "the banality of evil" finds expression in Karl's story – he was not an exceptional sadist but rather an ordinary young man who surrendered his moral autonomy to authority and ideology. The Holocaust legacy extends beyond Germany to raise uncomfortable questions for other nations as well. The world's failure to intervene, restrictive immigration policies that trapped Jews in Nazi Europe, and the willingness of local populations across Europe to collaborate all represent forms of responsibility that various societies have been reluctant to acknowledge. The widespread desire to "move on" after atrocity often conflicts with victims' need for acknowledgment and justice. This tension between remembering and forgetting, between holding accountable and moving forward, remains unresolved. While some argue that dwelling on past crimes prevents healing, others insist that genuine reconciliation requires truth-telling and accountability. The Holocaust thus becomes not merely a historical event but an ongoing moral challenge that each generation must confront anew.

Chapter 6: Beyond the Holocaust: Forgiveness in Other Genocides and Atrocities

The moral questions raised by Simon's encounter with Karl resonate far beyond the specific context of the Holocaust, illuminating similar dilemmas in other genocides and mass atrocities throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries. These parallels reveal both common patterns in human responses to extreme violence and important contextual differences that shape possibilities for reconciliation. The Cambodian genocide under the Khmer Rouge (1975-1979) offers one striking parallel. Survivor Dith Pran distinguishes between the top leadership who designed the killing and the ordinary soldiers who carried out orders. "I could never forgive or forget what the Khmer Rouge leadership has done to me, my family, or friends," he states, but adds that he could forgive the soldiers who "were taught to kill" and "were brainwashed." This nuanced approach acknowledges the moral complexity of evaluating guilt in systems where refusing orders often meant death for oneself and one's family. South Africa's post-apartheid transition introduced a different model through its Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who chaired the Commission, embraced a philosophy of "restorative justice" rather than retribution. He observed that many victims who testified about horrific torture were "ready to forgive" their perpetrators when they fully acknowledged their crimes. Tutu's approach, grounded in his Christian faith and African concept of ubuntu (shared humanity), emphasized that "without forgiveness, there is no future." In post-genocide Rwanda, communities implemented traditional gacaca courts where perpetrators confronted survivors face-to-face. Some Tutsi survivors found themselves able to forgive Hutu neighbors who had participated in killing their families, particularly when perpetrators demonstrated genuine remorse and made concrete efforts at restitution. Others found such forgiveness impossible, highlighting that no single approach to reconciliation works for all victims. The Bosnian genocide of the 1990s presents particularly relevant parallels to the Holocaust, as it occurred in Europe and involved ethnic cleansing justified by nationalist ideology. Bosnian survivor Sven Alkalaj notes that "clear parallels exist in regard to the worth of human life" while acknowledging that "recognition of guilt" must precede any possibility of reconciliation. Without such recognition, forgiveness becomes hollow. These diverse experiences suggest several common insights: genuine reconciliation requires truth-telling rather than amnesia; forgiveness cannot be demanded from victims but must remain their sovereign choice; structural justice must accompany individual forgiveness; and healing after atrocity typically involves generations rather than years. At the same time, different cultural, religious, and political contexts create varied pathways toward rebuilding shattered societies. The expanding field of transitional justice continues to wrestle with the fundamental tension between backward-looking accountability and forward-looking reconciliation. Simon's dilemma thus becomes a lens through which to examine one of humanity's most persistent challenges: how to move forward after seemingly unforgivable acts without either trivializing suffering or remaining trapped in cycles of vengeance.

Chapter 7: The Ethical Question: Justice, Reconciliation and Healing

At its core, the dilemma presented by Karl's request for forgiveness reveals a profound tension between justice and mercy that remains unresolved in human ethical thinking. This tension manifests in multiple dimensions – individual versus collective, legal versus moral, practical versus ideal – and continues to challenge our understanding of what healing means after massive moral rupture. Justice demands accountability for crimes committed. Many respondents to Simon's story insist that forgiveness without consequences undermines moral order – what philosopher Hannah Arendt called "cheap grace." Legal theorist Lawrence Langer argues that some crimes are simply "unforgivable" because they "burst the frame of conventional judgmental language." The Holocaust represents such a radical evil that traditional moral categories seem inadequate. From this perspective, Simon's refusal to forgive upholds the moral gravity of what occurred and honors the memory of those who cannot speak for themselves. Yet others point to the transformative potential of mercy. Rabbi Harold Kushner suggests that refusing to forgive can keep victims "chained" to their perpetrators through hatred. Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard frames forgiveness not as absolving guilt but as "an opportunity for the inner transformation of both victim and perpetrator." These perspectives see reconciliation as necessary for psychological and social healing, even after the most grievous wrongs. The practical dimension cannot be ignored. Societies emerging from mass atrocity must find ways to live together again. South African judge Albie Sachs observed that after apartheid, "the victims and the perpetrators... have to live in the same country." This reality forces pragmatic considerations alongside moral ones. Is justice without reconciliation sustainable? Is reconciliation without justice meaningful? Different societies have struck different balances, from the prosecutorial focus of Nuremberg to the truth-telling emphasis of South Africa. Individual survivors navigate these tensions in deeply personal ways. Some find that forgiveness liberates them from the burden of hatred, while others experience demands for forgiveness as a second victimization. Psychiatrist Judith Herman notes that trauma recovery follows its own timeline and cannot be rushed to satisfy others' desires for closure. True healing must center the needs of victims rather than the comfort of perpetrators or bystanders. Perhaps most challenging is the question of what constitutes genuine repentance. Karl's deathbed confession came when he had nothing left to lose and no opportunity to demonstrate changed behavior through action. As Maimonides taught, true repentance can only be confirmed when a person encounters the same situation again and chooses differently. Karl's impending death made this impossible, leaving the sincerity of his remorse forever ambiguous. These unresolved tensions reflect the inherent limitations of human moral frameworks when confronting extreme evil. They remind us that there are no easy formulas for healing after atrocity. Each victim must find their own path, each society its own balance between remembering and moving forward. What remains clear is that genuine reconciliation requires truth, justice, and above all, respect for the agency and dignity of those who have suffered.

Summary

Throughout this exploration of forgiveness, memory, and atrocity, a fundamental tension emerges between justice and mercy, between honoring victims and enabling healing. This tension is not merely theoretical but deeply practical – it shapes how individuals recover from trauma, how societies rebuild after conflict, and how humanity responds to its darkest capabilities. The narrative reveals that forgiveness after mass atrocity is neither a simple moral obligation nor an impossible ideal, but rather a complex human process with profound ethical, psychological, theological, and political dimensions. The lessons of this moral confrontation extend far beyond its historical context. First, we must recognize that genuine reconciliation requires truth rather than amnesia – societies that bury their painful histories rather than confronting them honestly remain vulnerable to repeating them. Second, we must acknowledge that forgiveness is always the sovereign right of victims, never to be demanded or expected by perpetrators or bystanders. Third, we must understand that healing after atrocity involves structural justice alongside individual forgiveness – personal transformation must be accompanied by institutional change. Finally, perhaps most challenging, we must accept that some moral dilemmas offer no perfect resolution – the human condition sometimes places us in situations where every available choice carries its own burden of loss. The most profound wisdom may lie not in finding definitive answers but in continuing to grapple with the questions, holding space for both justice and compassion in our broken world.

Best Quote

“To forgive without justice is a self-satisfying weakness. Justice without love is a simulation of strength.” ― Hans Habe, The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness

Review Summary

Strengths: The review effectively sets the stage by describing the intense and morally complex situation faced by Simon Wiesenthal, capturing the emotional gravity and philosophical depth of the narrative. It highlights the transformation and internal conflict of the young Nazi, Karl, providing a nuanced view of his past and present.\nOverall Sentiment: The review conveys a mixed sentiment, focusing on the moral and ethical dilemmas presented in the story. It suggests a deep engagement with the philosophical questions raised by the narrative, rather than a straightforward endorsement or criticism.\nKey Takeaway: The review emphasizes the central philosophical question of forgiveness and moral responsibility, as Wiesenthal is confronted with the decision of whether to forgive a dying Nazi soldier for his past atrocities. This dilemma serves as the core around which the story and its moral inquiries revolve.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.