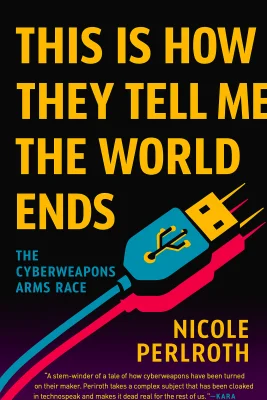

This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends

The Cyberweapons Arms Race

Categories

Business, Nonfiction, Science, History, Politics, Technology, Audiobook, Military Fiction, Computer Science, War

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2021

Publisher

Bloomsbury Publishing

Language

English

ISBN13

9781635576054

File Download

PDF | EPUB

This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends Plot Summary

Introduction

In a windowless room at Fort Meade, Maryland in 1998, a small team of NSA analysts made a startling discovery. They had found a way to remotely access the control systems of a major European power plant without leaving a trace. This capability, kept secret for years, marked the beginning of a new era in warfare - one where nations could inflict damage on adversaries without firing a single bullet or crossing any borders. The digital arsenal that emerged from these early experiments has transformed global security in ways few could have imagined. From Soviet bugs in American typewriters to sophisticated malware capable of destroying nuclear centrifuges, the evolution of cyber weapons reveals not just technological innovation, but a profound shift in how nations project power and conduct espionage. This journey illuminates the dangers of a world where offensive capabilities consistently outpace defensive measures, where weapons developed in secret inevitably escape control, and where the democratization of digital tools means that capabilities once reserved for superpowers are now available to smaller nations and even non-state actors. For anyone seeking to understand the invisible battles shaping our modern world, the story of these digital weapons and their consequences has become essential knowledge for navigating our increasingly vulnerable digital society.

Chapter 1: The Invisible Battlefield: From Soviet Typewriters to Digital Espionage (1980s-2000s)

The digital battlefield emerged silently during the Cold War's final decade, far from the nuclear arsenals and conventional military deployments that dominated headlines. In 1983, American embassy workers in Moscow began to suspect their communications were being compromised. This suspicion led to Project Gunman, a classified six-month NSA operation that would uncover an astonishing Soviet capability: typewriters with embedded listening devices that could record every keystroke through magnetic disturbances and transmit the data to nearby Soviet listening posts. The discovery shocked American intelligence officials who realized that encryption alone wasn't enough - the Soviets were capturing information before it could even be encrypted. This early incident catalyzed the development of America's offensive cyber capabilities. James Gosler, often called the godfather of American cyberwar, used the typewriter discovery to advocate for the United States to develop its own digital exploitation programs. "We were lucky beyond belief to discover we were being had," Gosler noted. "Or we would still be using those damn typewriters." His warnings gained traction, and by the mid-1990s, as the internet expanded rapidly, the NSA began shifting from passive signals intelligence to active exploitation, searching for vulnerabilities in hardware and software that could be leveraged for intelligence gathering. The September 11 attacks in 2001 accelerated this transformation dramatically. Intelligence agencies faced enormous pressure to collect more data on potential threats, leading to unprecedented growth in digital surveillance and exploitation programs. The NSA's Tailored Access Operations (TAO) unit expanded from hundreds to thousands of hackers, developing and deploying digital implants in computer systems around the world. By 2008, the NSA was managing tens of thousands of these implants, with plans to scale into the millions. What had once been a small, specialized field had become a central pillar of national security strategy. As the digital battlefield expanded, other nations began developing their own capabilities. The discovery of sophisticated Chinese intrusions into U.S. networks, dubbed Operation Aurora in 2009, revealed that America was no longer alone in this domain. China had systematically targeted dozens of American companies, including Google, Adobe, and Juniper Networks, stealing intellectual property and sensitive data. This massive theft, described by NSA Director Keith Alexander as "the greatest transfer of wealth in history," demonstrated how digital espionage could serve economic as well as military objectives. By the early 2000s, the invisible battlefield had become increasingly crowded and complex. Nations were investing billions in developing both offensive and defensive capabilities, with the United States maintaining a significant lead but others rapidly catching up. The tools and techniques pioneered during this period - from network exploitation to data exfiltration - laid the groundwork for what would follow: the evolution from espionage to active disruption and destruction. As one NSA veteran observed, "We spent decades building the perfect digital spy agency, only to discover we had actually been building an arsenal for a new kind of war."

Chapter 2: Crossing the Rubicon: Stuxnet and the Dawn of Cyber Weapons (2010)

In 2007, as pressure mounted from Israel to take military action against Iran's nuclear program, President George W. Bush found himself in need of a third option beyond diplomacy and conventional warfare. NSA Director Keith Alexander proposed an audacious alternative: a cyberattack that could physically damage Iran's uranium enrichment centrifuges without leaving a trace. This operation, code-named Olympic Games, would become the world's first acknowledged digital weapon designed to cause physical destruction in another country. Olympic Games represented an unprecedented collaboration between the NSA, CIA, Israel's Unit 8200, and American national laboratories. Teams of hackers, spies, and nuclear physicists worked together to develop a weapon that could infiltrate Iran's air-gapped systems at the Natanz nuclear facility. The weapon they created, later dubbed Stuxnet, utilized a chain of four zero-day exploits - previously unknown software vulnerabilities - to spread and execute its payload. The worm was designed to silently manipulate the speed of Iran's centrifuge rotors, causing them to spin out of control while simultaneously sending false data to monitoring systems to mask the attack. Stuxnet successfully infiltrated Natanz and began destroying centrifuges in late 2008. By 2010, it had destroyed approximately 1,000 of Iran's centrifuges, setting back the country's nuclear program by years. Iranian technicians were baffled by the failures, initially suspecting sabotage by insiders rather than a cyberattack. The operation appeared to be working perfectly - until a programming error allowed Stuxnet to spread beyond its intended target. The worm began appearing on computers worldwide, alerting security researchers to its existence. German industrial security specialist Ralph Langner was among the first to analyze the code and recognize its true purpose. "This is not about espionage," he declared in a TED Talk. "This is about destroying targets." The implications were profound. Stuxnet demonstrated that cyberweapons could achieve effects previously possible only through conventional military strikes. It also revealed the vulnerability of critical infrastructure to digital attacks. Most importantly, it showed other nations what was possible, accelerating a global cyber arms race. The crossing of this digital Rubicon fundamentally altered the landscape of international security. As former NSA Director Michael Hayden later observed, "This has a whiff of August 1945. Somebody just used a new weapon, and this weapon will not be put back in the box." Iran, the target of Stuxnet, responded by rapidly developing its own cyber capabilities. Within two years, Iranian hackers launched a retaliatory attack against Saudi Aramco, destroying data on 30,000 computers. Russia, China, and North Korea accelerated their own programs, recognizing the strategic value of these new weapons. Stuxnet marked the moment when cyber operations evolved from espionage to active warfare - from stealing information to causing physical effects in the real world. The decision to deploy this weapon, while avoiding the bloodshed of conventional military action, opened a Pandora's box that would transform global security for decades to come. As one security researcher warned, "The biggest number of targets for such an attack are not in the Middle East. They are in Europe, Japan, and the United States."

Chapter 3: The Zero-Day Market: Commercialization of Digital Vulnerabilities (2002-2015)

The market for zero-day vulnerabilities - previously unknown software flaws that can be exploited before developers have a chance to fix them - emerged from humble beginnings in the early 2000s. In 2002, a cybersecurity company called iDefense pioneered the first public program to pay hackers for discovering security vulnerabilities. The initial bounties were modest - just $75 per bug - but they represented a fundamental shift in how security flaws were valued and traded. Before this formalized market emerged, hackers typically disclosed vulnerabilities on mailing lists like BugTraq for free, often to shame vendors into fixing their products. The landscape began to change dramatically when government agencies recognized the intelligence value of zero-day exploits. As early as the mid-1990s, boutique government contractors were quietly buying vulnerabilities from hackers on behalf of U.S. intelligence agencies. Former contractor Jimmy Sabien revealed that government agencies would pay up to $150,000 for a single exploit - far more than the few hundred dollars offered by public bug bounty programs. "Access," Sabien explained, "is king." This price disparity created a two-tiered market: one public, where vulnerabilities would be disclosed and patched, and another shadow market where exploits remained secret for intelligence and military purposes. By 2007, independent security researchers began publicly acknowledging the existence of this shadow market. Charlie Miller, a former NSA mathematician turned security researcher, published a paper detailing how he sold a Linux vulnerability to a U.S. government agency for $50,000. This revelation sparked debate within the security community about the ethics of selling vulnerabilities rather than disclosing them for patching. Meanwhile, specialized brokers emerged to connect talented hackers with government buyers. Adriel Desautels, who operated as one of America's preeminent zero-day brokers, explained his business model: "I just kept upping the asking price until I met resistance." Soon he was selling exploits for over $90,000 each. The market's expansion wasn't limited to the United States. As other nations recognized the strategic value of zero-days, they began developing their own acquisition programs. Israel, Britain, Russia, and others entered the market, driving prices even higher. By 2013, companies like Vupen in France, Hacking Team in Italy, and NSO Group in Israel were openly selling surveillance tools built around zero-day exploits to governments worldwide. These firms employed talented hackers to discover vulnerabilities in common software platforms and develop them into turnkey surveillance solutions. Chaouki Bekrar, Vupen's founder nicknamed the "Wolf of Vuln Street," openly advertised his company's mission to sell exploits exclusively to government clients. The ethical boundaries in this market remained dangerously undefined. While companies claimed they vetted clients to prevent sales to repressive regimes, reality often proved otherwise. In 2015, Italian firm Hacking Team was itself hacked, exposing its client list and business practices. Despite claiming to sell only to legitimate governments for law enforcement purposes, leaked documents revealed sales to countries with troubling human rights records, including Sudan, Ethiopia, and Bahrain. The technology was increasingly used to target dissidents, journalists, and human rights defenders worldwide. For Desautels, who discovered one of his exploits had been sold to Hacking Team and subsequently to Sudan, it was a moment of reckoning: "I'd never been so repulsed in my life. I always said when this business got dirty, I'd get out." By 2015, what had started as a modest effort to improve software security had transformed into a global arms race, with profound implications for national security and digital privacy. The commercialization of zero-days had democratized access to sophisticated cyber capabilities, allowing dozens of countries to acquire tools once reserved for the most advanced intelligence agencies. This proliferation would soon have devastating consequences as these weapons inevitably escaped control.

Chapter 4: State-Sponsored Attacks: Russia, China and Critical Infrastructure (2014-2017)

By 2014, Russia and China had established themselves as sophisticated cyber powers, each pursuing distinct strategies that reflected their broader geopolitical objectives. China's cyber operations focused primarily on massive intellectual property theft to fuel its economic growth. The 2009 Aurora operation targeting Google and dozens of other American companies was just the tip of the iceberg. By 2014, Chinese military hackers from PLA Unit 61398 had systematically stolen trillions of dollars worth of American intellectual property, from Google's source code to the designs for the F-35 fighter jet. This campaign represented what NSA Director Keith Alexander called "the greatest transfer of wealth in history." Russia, meanwhile, pursued a more aggressive strategy focused on critical infrastructure and political manipulation. In December 2015, Russian hackers from a group known as Sandworm executed an unprecedented attack on Ukraine's power grid, cutting electricity to nearly 250,000 people by remotely taking over power distribution centers. This marked the first confirmed cyberattack to disable a power grid, demonstrating Russia's willingness to cross thresholds that other nations had avoided. The attack served as a warning to Western nations about their own vulnerabilities - if Russia could turn off the lights in Ukraine, they could potentially do the same elsewhere. The targeting of critical infrastructure represented a dangerous escalation. By 2016, security researchers were detecting similar probing activities against power grids in the United States and Europe. Russian hackers gained access to control rooms of American electric utilities, potentially positioning themselves to cause widespread outages. As one security researcher explained, "They weren't there to steal information. They were there to learn how to take the system down." This activity coincided with Russia's broader campaign to undermine Western democracies, including the hacking and leaking of Democratic National Committee emails during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The culmination of this escalation came in June 2017 with the NotPetya attack. What began as a targeted strike against Ukraine during its independence holiday quickly spiraled into the most destructive cyberattack in history. By compromising Ukrainian tax software company Linkos Group, Russian hackers were able to distribute malware through a legitimate software update. When activated, the malware permanently encrypted computers' master boot records. Ukrainian government agencies, airports, power companies, banks, and media organizations were paralyzed within hours. But the attack didn't stop at Ukraine's borders - it spread globally through corporate networks, causing over $10 billion in damages worldwide. The NotPetya attack revealed how digital weapons had evolved from tools of espionage to instruments of genuine destruction. Shipping giant Maersk lost access to 49,000 laptops and 1,200 applications, forcing the company to rebuild its entire IT infrastructure over ten days. Pharmaceutical company Merck suffered production delays for critical vaccines. Even Russia's own Rosneft oil company was affected, highlighting how digital weapons can be impossible to contain once deployed. As one Ukrainian security expert observed: "They were experimenting with us. The question we should all be asking ourselves is what they will do next." By 2017, the targeting of critical infrastructure had become the new normal in state-sponsored cyber operations. The line between peacetime and conflict had blurred, with nations conducting operations that in a conventional context might be considered acts of war. This escalation prompted calls for new international norms and agreements to protect civilian infrastructure from cyberattacks, but with limited success. As Microsoft's president Brad Smith warned, "We need a Digital Geneva Convention that will commit governments to protecting civilians from nation-state attacks in times of peace."

Chapter 5: Shadow Brokers: When Weapons Escape Control (2016-2017)

In August 2016, a mysterious group calling themselves the "Shadow Brokers" announced they had stolen hacking tools from the NSA's elite Tailored Access Operations unit and began publishing them online. This unprecedented breach represented intelligence agencies' worst nightmare - their most sophisticated cyber weapons were now available to anyone with an internet connection. The Shadow Brokers initially attempted to auction these tools, but eventually released them freely, causing panic among security professionals worldwide. The leaked arsenal included numerous powerful exploits, but none more devastating than EternalBlue, a tool that exploited a vulnerability in Microsoft's Windows operating systems. NSA analysts had discovered this vulnerability around 2012 but kept it secret for over five years rather than disclosing it to Microsoft for patching, prioritizing offensive capabilities over the security of systems worldwide. Microsoft finally received information about the vulnerability in March 2017 and released a patch, but many systems remained unpatched when the Shadow Brokers published the exploit code in April. What followed was a cascade of devastating cyberattacks. In May 2017, North Korean hackers repurposed EternalBlue to create WannaCry, a ransomware worm that infected over 200,000 computers across 150 countries in just 24 hours. Hospitals in the United Kingdom had to turn away patients, factories shut down, and damages eventually reached hundreds of millions of dollars. Just one month later, Russian military intelligence deployed an even more sophisticated attack called NotPetya, which also leveraged EternalBlue. Initially targeting Ukraine, NotPetya spread globally, causing unprecedented destruction. Unlike WannaCry, NotPetya was designed not for profit but for maximum damage - it permanently encrypted victims' data with no possibility of recovery. The aftermath of these attacks triggered a reckoning within the cybersecurity community. Microsoft's president Brad Smith publicly condemned the NSA's practices, comparing the theft of their cyber weapons to "conventional weapons being stolen from a U.S. military base." He wrote: "This attack provides yet another example of why stockpiling of vulnerabilities by governments is such a problem. This is an emerging pattern in 2017. We have seen vulnerabilities stored by the CIA show up on WikiLeaks, and now this vulnerability stolen from the NSA has affected customers around the world." Inside the NSA, the Shadow Brokers leaks prompted a frantic hunt for the source of the breach, with investigators questioning whether it was the work of an insider or a sophisticated foreign intelligence operation. The agency's morale hit rock bottom as operations were compromised and trust eroded. Meanwhile, a disturbing revelation emerged: even before the Shadow Brokers leaks, Chinese hackers had discovered the NSA using these same exploits against their systems, captured them, and repurposed them for their own operations. This confirmed security experts' warnings that the "NOBUS" assumption ("Nobody But Us" could find these vulnerabilities) was dangerously flawed. By 2018, the United States was experiencing firsthand the consequences of its cyber arsenal escaping control. The NSA's leaked exploits, particularly EternalBlue, had evolved from classified intelligence tools into weapons being used against American networks with alarming frequency. In Allentown, Pennsylvania, the exploit was used to spread malware across city networks, wiping police databases and freezing surveillance systems. In Baltimore, Maryland - just a short drive from NSA headquarters - city services were paralyzed by attackers using the agency's own tools. The financial and social costs were enormous, with local governments facing difficult choices between paying ransoms or rebuilding systems from scratch. The Shadow Brokers saga demonstrated the inherent danger of stockpiling digital vulnerabilities - they can be stolen and turned against their creators or innocent third parties. What began as secret intelligence tools had transformed into weapons of mass digital destruction, with consequences that would reverberate through cyberspace for years to come. As one security researcher put it: "These are not just theoretical risks - we're watching the blowback in real time."

Chapter 6: Democratization of Cyber Capabilities: From Nations to Non-State Actors

By the mid-2010s, what had once been the exclusive domain of superpowers was rapidly becoming accessible to smaller nations and even non-state actors. This democratization of cyber capabilities fundamentally altered the global security landscape, creating new threats and vulnerabilities that traditional defense frameworks struggled to address. The barriers to entry had fallen so dramatically that virtually any motivated actor could acquire advanced cyber capabilities, either by developing them internally or purchasing them from commercial vendors. Iran's evolution as a cyber power exemplifies this trend. After Stuxnet damaged its nuclear program in 2010, Iran poured resources into developing its own cyber capabilities. Within just two years, Iranian hackers launched a retaliatory attack against Saudi Aramco, the world's richest oil company, destroying 30,000 computers and replacing their data with an image of a burning American flag. As Leon Panetta observed, "We were astounded that Iran could develop that kind of sophisticated virus. What it told us was that they were much further along in their capability than we gave them credit for." Iran followed this with attacks on American banks, demonstrating how quickly a determined nation could build offensive cyber capabilities from a standing start. North Korea similarly leveraged cyber operations to overcome its isolation and conventional military disadvantages. In 2014, North Korean hackers struck Sony Pictures in retaliation for a film depicting the assassination of Kim Jong-un. By 2017, they had weaponized leaked NSA exploits to create WannaCry, a ransomware attack that affected computers in 150 countries. Beyond destructive attacks, North Korea's hackers became adept at financial theft, stealing $81 million from Bangladesh's central bank and targeting cryptocurrency exchanges to generate hundreds of millions of dollars, effectively circumventing international sanctions. The proliferation extended to the private sector, where companies like NSO Group in Israel developed sophisticated surveillance tools that could remotely compromise smartphones without any user interaction. Their Pegasus spyware could capture everything from messages to location data to ambient sounds and images through the phone's microphone and camera. Initially marketed to Western democracies for counterterrorism, these tools soon spread to dozens of countries worldwide. By 2019, NSO's Pegasus had been identified targeting individuals in 45 countries, including journalists, human rights activists, and political dissidents. Perhaps most concerning was the emergence of a gray market where former intelligence operatives offered their services to the highest bidder. In the United Arab Emirates, former NSA hackers were recruited to Project Raven, a program that targeted journalists, human rights activists, and even American citizens. David Evenden, one of these former NSA analysts, described his growing discomfort as the mission expanded from tracking terrorists to hacking journalists and political opponents: "That was the moment I said, 'We shouldn't be doing this. This is not normal.'" The democratization of cyber capabilities created a world where the line between state and non-state actors became increasingly blurred. Criminal groups adopted nation-state techniques, while governments sometimes operated through proxies to maintain deniability. This convergence was exemplified by the rise of ransomware as a national security threat. By 2020, ransomware gangs were targeting hospitals, schools, and local governments with attacks sophisticated enough to be mistaken for state-sponsored operations. Some groups, like Russia-based DarkSide, operated with implicit state protection, creating a new category of threat that defied traditional categorization. This proliferation created unprecedented challenges for defenders. Organizations now faced threats from a diverse array of actors with varying motivations and capabilities. The traditional focus on nation-state threats had to expand to include criminal groups, hacktivists, and mercenaries. As one security researcher observed, "We've democratized capabilities that were once the sole province of the NSA and given them to anyone with an internet connection and basic technical skills. The genie is out of the bottle, and there's no putting it back."

Chapter 7: Digital Battlegrounds: Elections, Democracy and Information Warfare

The 2016 U.S. presidential election revealed a new dimension of cyber conflict that went beyond traditional hacking: the weaponization of information itself. Russia's multifaceted interference campaign combined conventional cyberattacks with sophisticated information operations, creating a playbook that would be replicated and refined in subsequent years. This convergence of hacking and disinformation represented perhaps the most significant threat to democratic institutions worldwide. Russia's operation began with traditional espionage tactics. In March 2016, Russian military intelligence hackers known as "Fancy Bear" gained access to the Democratic National Committee's networks and the email account of Hillary Clinton's campaign chairman, John Podesta. Rather than keeping this intelligence private, they weaponized it through strategic leaks. Working through cutouts like DCLeaks and WikiLeaks, and a persona called "Guccifer 2.0," they released damaging information at critical moments in the campaign, effectively turning stolen data into political ammunition. Simultaneously, Russia's Internet Research Agency (IRA) in St. Petersburg orchestrated a massive social media influence operation. They created thousands of fake American personas on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, built followings around divisive issues, and organized real-world events designed to inflame tensions. These trolls posed as everything from Black Lives Matter activists to Texas secessionists, exploiting America's social divisions with remarkable precision. By Election Day, their content had reached at least 126 million Americans on Facebook alone and generated 288 million Twitter impressions. The operation's sophistication stunned American intelligence officials. Russian operatives had conducted extensive reconnaissance, sending agents to nine states in 2014 to study American politics and identify societal fault lines. They created convincing fake accounts that accumulated hundreds of thousands of followers. Their content was designed to amplify existing divisions rather than create new ones, making the operation difficult to distinguish from authentic political discourse. As one analyst explained, "They weren't creating the divisions. The divisions were already there. They were just pouring gasoline on the fire." The Russian playbook quickly spread globally. Similar tactics were deployed in the 2017 French presidential election, the Brexit referendum, and numerous other democratic processes worldwide. Each iteration brought refinements: better operational security, more convincing personas, and increasingly sophisticated targeting. What began as relatively crude fake news evolved into precision-targeted influence operations leveraging advanced data analytics. By 2020, the threat landscape had grown even more complex, with Iran and China developing their own information warfare capabilities, targeting different aspects of the democratic process. Beyond elections, information warfare expanded to target public health initiatives, racial justice movements, and other pillars of civil society. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Russian and Chinese disinformation campaigns spread conspiracy theories about the virus's origin and undermined confidence in vaccines. These operations exploited existing societal tensions and trust gaps, making them particularly effective in polarized societies. As one intelligence official noted: "The mantra of Russian active measures is this: 'Win through force of politics rather than the politics of force.' What that means is go into your adversary and tie them up in politics to the point where they are in such disarray that you are free to do what you will." The weaponization of information represented a fundamental challenge to democratic societies. Unlike traditional cyberattacks that target technology, these operations exploited the cognitive vulnerabilities of citizens and the open nature of democratic discourse. They turned strengths - free speech, open debate, and pluralism - into potential vulnerabilities. Defending against these threats required new approaches that balanced security concerns with democratic values, technical solutions with media literacy, and government action with private sector cooperation. As one expert observed, "We've spent decades building defenses against missiles and tanks, but we're just beginning to understand how to defend our information ecosystem - the very foundation of democratic decision-making."

Summary

The evolution of cyber weapons represents one of the most significant shifts in global security since the development of nuclear arms. What began as specialized tools in the hands of superpowers has transformed into widely available capabilities that have democratized warfare, espionage, and sabotage. Throughout this transformation, we've witnessed a consistent pattern: innovations in offensive capabilities outpacing defensive measures, weapons escaping their creators' control, and the blurring of lines between state and non-state actors. The digital arsenal has fundamentally altered power dynamics, allowing smaller nations like Iran and North Korea to project influence far beyond their conventional military capabilities, while creating new vulnerabilities in the increasingly connected infrastructure of developed nations. The lessons from this evolution offer critical guidance for navigating our digital future. First, we must recognize that any weapon developed in secret will eventually escape - whether through leaks, theft, or independent discovery - and potentially be turned against its creators. Second, the absence of established norms and treaties in cyberspace has created a dangerous free-for-all that threatens critical infrastructure, economic stability, and democratic processes worldwide. Finally, the privatization of advanced capabilities means that even as governments grapple with these challenges, corporations and individuals must take unprecedented responsibility for their own security. As we continue deeper into this digital era, establishing international frameworks that balance security needs with human rights protections has become not just desirable but essential for preventing the digital arsenal from unleashing its full destructive potential.

Best Quote

“In the United States, though, convenience was everything; it still is. We were plugging anything we could into the internet, at a rate of 127 devices a second. We had bought into Silicon Valley’s promise of a frictionless society. There wasn’t a single area of our lives that wasn’t touched by the web. We could now control our entire lives, economy, and grid via a remote web control. And we had never paused to think that, along the way, we were creating the world’s largest attack surface.” ― Nicole Perlroth, This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends: The Cyberweapons Arms Race

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights the book's ability to provide a "frightening" and "terrifying" insight into global cyber warfare, emphasizing its readability and fascinating content. It praises the book for its extensive and illuminating exploration of cyber threats, particularly the Zero Day software bug. Weaknesses: Not explicitly mentioned. Overall Sentiment: Enthusiastic Key Takeaway: Nicole Perlroth's book offers a compelling and alarming examination of hacking and cyber threats, particularly focusing on the Zero Day bug's potential to cause widespread disruption. The book effectively changes the reader's perspective on technology and its vulnerabilities.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.