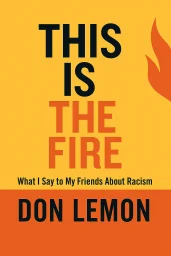

This Is the Fire

What I Say to My Friends About Racism

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Memoir, Politics, Audiobook, Autobiography, Social Justice, Biography Memoir, Race

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2021

Publisher

Little, Brown and Company

Language

English

ASIN

031627352X

ISBN

031627352X

ISBN13

9780316273527

File Download

PDF | EPUB

This Is the Fire Plot Summary

Introduction

History often moves in a spiral rather than a straight line, with periods of progress followed by backlash and regression. Nowhere is this pattern more evident than in America's long, painful struggle with white supremacy. From the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in 1619 to the racial reckonings of the 21st century, this struggle has defined much of the American experience, shaping our institutions, politics, and national identity in profound ways. The story of American racial history is not simply a chronicle of oppression, but also one of remarkable resilience and resistance. For every system designed to subjugate people of color, there emerged movements to dismantle it. For every act of racial violence, there came voices of moral courage. Understanding this dynamic interplay between oppression and resistance is crucial to making sense of America's past and charting a path toward a more equitable future. This book illuminates how white supremacy became embedded in American society, how it evolved over time, and how it continues to shape our lives today. It's essential reading for anyone seeking to understand why racial disparities persist despite centuries of struggle, and why conversations about race remain so difficult yet necessary in contemporary America.

Chapter 1: The Long Shadow: Origins of American Racial Hierarchy (1619-1865)

In August 1619, about a month after legislative representatives from eleven New World settlements met in Jamestown to establish foundations for democracy, a ship arrived at nearby Point Comfort carrying approximately two dozen Angolan men and women who were sold into slavery. This juxtaposition—democracy's birth alongside human bondage—would come to define America's foundational contradiction. The dream of democracy and the nightmare of slavery were born in the same urgent breath, establishing a pattern that would haunt the nation for centuries to come. As the colonies developed, racial hierarchy was codified through law and custom. The economic imperative for cheap labor, particularly on southern plantations, drove the expansion of slavery. By the 1700s, complex legal codes emerged distinguishing between "white" and "black," with increasingly rigid definitions of racial categories. The drafters of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution grappled with this contradiction—proclaiming universal rights while protecting slavery. Thomas Jefferson, who owned over 600 enslaved people during his lifetime, wrote eloquently about equality while designing a system that denied it to millions. The psychological architecture of white supremacy required elaborate justifications. Pseudo-scientific racism emerged, with prominent thinkers claiming biological differences between races. Religious leaders found biblical rationales for slavery. Cultural depictions of Black people as inferior became commonplace. This wasn't merely personal prejudice but an interlocking system of economic, legal, political, and cultural practices designed to maintain power and extract wealth. As historian Isabel Wilkerson notes, race became not just a classification but a caste system with profound implications for all aspects of American life. Resistance to this system was constant. The German Coast Uprising of 1811 in Louisiana represented the largest slave rebellion in U.S. history, with hundreds marching for freedom before being brutally suppressed. Figures like Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman challenged the system through various means. The Underground Railroad helped thousands escape bondage. White abolitionists joined the cause, though often with complicated motivations and perspectives limited by their era's racial thinking. By the time civil war erupted in 1861, slavery had become the central issue dividing the nation, despite attempts to frame the conflict around states' rights or economic differences. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and later the 13th Amendment formally ended slavery, but by then, white supremacy had been woven deeply into the fabric of American society. The legal end of slavery would mark only the beginning of a new chapter in America's racial struggle, as the institutions, attitudes, and power structures built during these first 246 years would cast a long shadow over generations to come.

Chapter 2: Slavery's Legacy: From Reconstruction to Jim Crow (1865-1950s)

The period following the Civil War, known as Reconstruction, offered a brief, tantalizing glimpse of what a more equitable America might look like. From 1865 to 1877, federal troops occupied the South, protecting newly freed Black citizens as they exercised their rights. Black men voted, held public office, and helped establish the South's first public education systems. The 14th Amendment granted citizenship to all persons born in the United States, and the 15th Amendment prohibited denying voting rights based on race. For a moment, America seemed poised to fulfill its democratic promise. This progress triggered an intense backlash. As federal troops withdrew in 1877, white supremacist violence surged across the South. The Ku Klux Klan and similar organizations terrorized Black communities, while "Redeemer" governments systematically dismantled Reconstruction reforms. What followed was not merely a regression but a calculated reimposition of racial hierarchy through new means. In 1896, the Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v. Ferguson enshrined the doctrine of "separate but equal," giving constitutional blessing to segregation for the next half-century. Jim Crow laws permeated every aspect of daily life. Literacy tests and poll taxes effectively disenfranchised Black voters. Signs designating "White" and "Colored" facilities became ubiquitous across the South. Miscegenation laws criminalized interracial relationships. Beyond legal segregation, extralegal violence enforced the racial order. Between 1882 and 1968, more than 4,400 Black Americans were lynched, often in carnival-like public spectacles designed to terrorize entire communities. When Black communities achieved economic success despite these obstacles—as in Tulsa's "Black Wall Street" in 1921 or Rosewood, Florida, in 1923—they faced violent destruction from white mobs. Cultural reinforcement of white supremacy took on new dimensions during this era. D.W. Griffith's 1915 film "The Birth of a Nation" glorified the Ku Klux Klan and portrayed Black Americans as dangerous and inferior. Confederate monuments sprung up across the South, not immediately after the Civil War but during the height of Jim Crow, serving to mythologize the "Lost Cause" and intimidate Black citizens. Popular culture embraced racist caricatures through minstrel shows, advertising, and early Hollywood films. The Great Migration, beginning around 1916, saw millions of Black Americans flee the South for northern and western cities. While escaping the most brutal aspects of Jim Crow, they encountered new forms of discrimination: restrictive covenants in housing, workplace discrimination, and informal segregation. The northern exodus changed both regions forever, spreading southern music, culture, and cuisine nationwide while forcing northern cities to confront their own racial attitudes. By the 1950s, the foundation for America's civil rights struggle was taking shape. Organizations like the NAACP had won important legal victories, most notably Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which declared school segregation unconstitutional. Black veterans returning from World War II, having fought fascism abroad, were increasingly unwilling to accept second-class citizenship at home. The contradictions between America's Cold War rhetoric about freedom and its treatment of Black citizens became increasingly untenable. The stage was set for a new chapter in America's racial struggle, one that would challenge Jim Crow directly and demand that America finally live up to its founding ideals.

Chapter 3: Civil Rights Era: Resistance and Awakening (1950s-1970s)

The modern Civil Rights Movement emerged from grassroots organizing and deep historical currents. In December 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus, sparking a 381-day boycott that catapulted a young minister named Martin Luther King Jr. to national prominence. The Montgomery Bus Boycott demonstrated the power of nonviolent direct action and economic pressure, strategies that would define much of the movement. It also established a template: local acts of resistance, often led by women and ordinary citizens, that connected to national organizations and broader strategies. The late 1950s and early 1960s saw escalating confrontations across the South. In 1960, four Black college students sat at a whites-only lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, inspiring similar sit-ins nationwide. Freedom Riders challenged segregated interstate transportation, facing brutal violence. In Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963, police commissioner Bull Connor's use of fire hoses and attack dogs against peaceful protesters, including children, shocked the nation's conscience when broadcast on television. That same year, over 250,000 people participated in the March on Washington, where King delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. The movement's moral clarity and discipline produced tangible results. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination in public accommodations and employment. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 dismantled barriers to political participation. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 addressed discrimination in housing. These legislative victories, while imperfect, represented the most significant advance in civil rights since Reconstruction and demonstrated how sustained grassroots activism could transform national policy. Yet as legal segregation crumbled, more intractable problems emerged. Northern ghettos, created through decades of discriminatory housing policies, continued to trap Black communities in cycles of poverty and disinvestment. When Martin Luther King Jr. brought his campaign north to Chicago in 1966, he encountered resistance as fierce as anything in the South. His assassination in 1968, along with those of Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, and many lesser-known activists, underscored the violent backlash against racial progress. Urban uprisings in Watts, Detroit, Newark, and other cities between 1965 and 1968 reflected frustration with persistent inequality and police brutality. The late 1960s saw the rise of more militant approaches, exemplified by the Black Power movement. Organizations like the Black Panther Party established community programs while advocating armed self-defense. Cultural nationalism flourished, with "Black is Beautiful" challenging Eurocentric beauty standards and African American studies programs emerging on college campuses. Meanwhile, Richard Nixon's "Southern Strategy" began reconfiguring American politics around coded appeals to white racial resentment. By the 1970s, the heroic phase of the Civil Rights Movement had given way to complex struggles over implementation and interpretation. School desegregation through busing sparked fierce resistance in Boston and other northern cities. Affirmative action policies generated both opportunity and controversy. The movement's successes transformed American society and inspired parallel movements for women, Latinos, Native Americans, LGBTQ+ people, and others. Yet its ultimate goal—a society where race no longer determined one's life chances—remained elusive, as white supremacy adapted and evolved in response to each challenge.

Chapter 4: Media and Mythology: Shaping Race Narratives (1970s-2000s)

As legal segregation faded into history, the battleground for racial narratives shifted increasingly to media and popular culture. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, television emerged as the dominant medium shaping American perceptions about race. Shows like "The Jeffersons" and "Good Times" brought Black families into white living rooms, yet often reinforced stereotypes while attempting to challenge them. News coverage of urban issues increasingly focused on crime and decay, with coded language about "inner cities" and "welfare queens" replacing explicitly racist terminology but preserving similar narratives. Hollywood's approach to race evolved significantly during this period. The blaxploitation films of the early 1970s offered complex legacies—providing unprecedented opportunities for Black actors and directors while often trafficking in problematic imagery. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, filmmakers like Spike Lee and John Singleton were creating nuanced explorations of racial dynamics, though mainstream cinema continued to center white perspectives. Films about race that gained widespread acclaim, like "Driving Miss Daisy" and "The Help," tended to frame racial progress as primarily the story of white moral growth rather than Black resistance. The 1990s saw explosive moments that revealed America's continued racial divisions. The 1991 beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police officers, captured on video, and the subsequent acquittal of those officers sparked days of unrest. The O.J. Simpson trial in 1995 exposed starkly different perceptions of the criminal justice system between Black and white Americans. These events played out on the newly 24-hour cable news landscape, which often prioritized sensationalism over context and understanding. Meanwhile, a powerful counternarrative was taking shape about America's racial history. Confederate monuments were increasingly defended as "heritage not hate," while school textbooks minimized slavery's centrality to the Civil War. The "Lost Cause" mythology—portraying the Confederacy as noble defenders of states' rights rather than slavery—gained renewed currency. This revisionism wasn't merely about the past; it shaped contemporary political alignments, with appeals to racial resentment becoming increasingly central to conservative messaging, though usually through coded language about crime, welfare, and "traditional values." Popular music revealed both racial divisions and points of connection. Hip-hop emerged from marginalized Black communities to become a global cultural force, though mainstream America often embraced the music while rejecting its political messages. The gangsta rap of the 1990s sparked moral panics while reflecting harsh realities of urban disinvestment and the war on drugs. White artists from Elvis to Eminem built careers appropriating Black musical innovations, raising complicated questions about cultural exchange versus exploitation. By the early 2000s, many Americans embraced a narrative of racial progress that acknowledged historical injustices while suggesting they had been largely overcome. The election of Barack Obama in 2008 was widely interpreted as evidence of a "post-racial America." Yet this narrative coexisted uneasily with persistent racial disparities in wealth, education, incarceration, and health outcomes. The media environment, increasingly fragmented by cable news and the early internet, allowed Americans to consume information that reinforced their existing racial perspectives rather than challenging them, setting the stage for even deeper polarization in the decades to come.

Chapter 5: Economic Inequality: The Cost of Racial Injustice

The economic dimension of racial inequality represents perhaps the most persistent legacy of white supremacy in American life. The racial wealth gap—with the median white family possessing nearly ten times the wealth of the median Black family as of 2020—stems directly from historical policies and practices that systematically prevented wealth accumulation in communities of color. This disparity cannot be explained by education, income, or individual choices; it reflects centuries of structural disadvantage compounded across generations. Slavery itself was fundamentally an economic system that generated enormous wealth—not just for southern plantation owners but for northern banks, insurance companies, and textile manufacturers. After emancipation, policies like sharecropping and convict leasing continued to extract labor from Black communities while preventing economic independence. During the early 20th century, when many white Americans were building middle-class wealth through homeownership, Black Americans faced redlining, restrictive covenants, and outright violence when attempting to move into desirable neighborhoods. The post-World War II economic boom, often remembered as a period of widespread prosperity, was explicitly designed to exclude Black Americans. The GI Bill, which helped millions of white veterans attend college and purchase homes, was administered in ways that denied these benefits to Black veterans. Federal housing programs subsidized white suburbanization while disinvesting from increasingly segregated urban cores. Even when Black families overcame these barriers to purchase homes, their properties typically appreciated at lower rates than comparable white-owned homes, creating a compounding disadvantage in the primary vehicle for middle-class wealth building. The late 20th century brought new economic challenges with particular impact on Black communities. Deindustrialization eliminated many manufacturing jobs that had provided pathways to middle-class stability. The war on drugs devastated Black neighborhoods through mass incarceration, creating a permanent underclass of formerly imprisoned people facing legal discrimination in employment and housing. Predatory financial practices targeted communities of color, from the subprime mortgage crisis to payday lending, extracting wealth rather than building it. Education, often promoted as the great equalizer, has failed to overcome these structural disadvantages. School funding tied to local property taxes ensures that wealthy districts can provide better educational resources than poor ones, perpetuating inequality across generations. Even when Black Americans achieve higher education, they typically carry more student debt and receive less return on their educational investment than white peers with similar credentials. This "education debt" reflects both current discrimination and the cumulative effects of historical disadvantage. The economic costs of racism extend beyond communities of color to affect the entire nation. Economists estimate that racial discrimination and inequality reduce overall economic output by trillions of dollars through wasted human potential, reduced consumer spending, and increased social costs. As America becomes increasingly diverse, with people of color projected to constitute a majority by mid-century, addressing these disparities becomes not just a moral imperative but an economic necessity. The persistence of racial economic inequality reveals how deeply white supremacy has been woven into American capitalism itself, requiring not just individual attitude changes but fundamental structural reforms to create a truly equitable economy.

Chapter 6: Modern Movements: From Obama to BLM (2008-2020)

Barack Obama's election in 2008 represented a watershed moment in American racial history. His victory seemed to validate the ideal that anyone could achieve success regardless of race, leading many to declare the dawn of a "post-racial" era. Obama himself walked a careful line, rarely addressing race explicitly except in moments of crisis. His presidency embodied a particular approach to racial progress: excellence, respectability, and working within established institutions rather than challenging their fundamental structures. The limits of this approach soon became apparent. Obama faced unprecedented obstruction and delegitimization, including the "birther" conspiracy theory championed by Donald Trump. When Obama did address racial issues—commenting that police had "acted stupidly" in arresting Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. on his own porch, or noting that if he had a son, "he'd look like Trayvon Martin"—he faced fierce backlash. The Tea Party movement, ostensibly about fiscal conservatism, frequently employed racial imagery and rhetoric against the first Black president. Meanwhile, smartphones and social media were transforming how Americans witnessed racial injustice. The 2014 police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, catalyzed what would become the Black Lives Matter movement. Unlike earlier civil rights organizations with centralized leadership, BLM emerged as a decentralized network emphasizing local organizing and intersectionality—recognizing how race intersects with gender, sexuality, class, and other identities. The movement highlighted not just high-profile killings but the everyday indignities and dangers faced by Black Americans in encounters with police and other institutions. The 2016 election of Donald Trump represented a sharp pivot in America's racial politics. Trump abandoned the coded language of previous decades for more explicit appeals to white grievance. His administration rolled back civil rights enforcement, implemented restrictive immigration policies targeting people of color, and defended Confederate monuments as "heritage." This approach energized a segment of white America that felt threatened by demographic and cultural change, while galvanizing opposition among those committed to racial justice. The COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in 2020, laid bare America's persistent racial inequalities. Black, Latino, and Native American communities suffered disproportionately high infection and death rates, reflecting disparities in healthcare access, employment conditions, and housing. The economic fallout likewise hit communities of color hardest. These disparities underscored how racism operates not just through individual bigotry but through systemic structures that produce unequal outcomes regardless of intent. The May 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, captured on video as Floyd repeatedly gasped "I can't breathe," ignited the largest protest movement in American history. Demonstrations spread to over 2,000 cities and towns, drawing unprecedented participation from white Americans alongside communities of color. Corporate America rushed to express solidarity, though often without addressing substantive change. The moment represented both the mainstreaming of racial justice concerns and the risk of symbolic gestures without structural reform. By late 2020, America found itself in what might be called a Third Reconstruction—a fundamental struggle over the nation's racial future comparable to the post-Civil War era and the mid-20th century Civil Rights Movement. On one side stood a diverse coalition demanding fundamental transformation of American institutions; on the other, forces committed to preserving existing hierarchies, whether through explicit white nationalism or more subtle defense of the status quo. The outcome of this struggle would shape American society for generations to come.

Chapter 7: Building Bridges: Pathways to Reconciliation and Progress

Creating a more equitable America requires action at multiple levels, from personal growth to policy change. Individual consciousness-raising remains essential but insufficient. Many Americans have begun examining their own biases and privileges through reading, conversation, and uncomfortable self-reflection. This personal work lays necessary groundwork but must connect to broader collective action to achieve meaningful change. True progress requires both internal transformation and external reform, with each reinforcing the other. Education represents a crucial battleground. Efforts to incorporate honest historical education about slavery, segregation, and systemic racism face fierce resistance from those who prefer comforting myths to difficult truths. Yet understanding how white supremacy shaped American institutions is essential to reforming them. Beyond formal education, cultural institutions like museums, media, and the arts play vital roles in expanding American historical consciousness and fostering empathy across racial lines. Projects like the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, demonstrate how confronting painful history can become a pathway to healing rather than division. Political and policy reform remains indispensable. Voting rights protection, criminal justice reform, healthcare access, and affordable housing represent critical priorities for addressing structural racism. Economic policies that address the racial wealth gap—from targeted investment in historically marginalized communities to consideration of reparations—would help repair centuries of economic extraction. Environmental justice initiatives would address the disproportionate pollution burden placed on communities of color. These policy approaches require sustained political engagement and coalition-building, connecting racial justice to broader movements for economic and social equity. Religious and spiritual communities have significant roles to play. Faith traditions have sometimes reinforced racial hierarchy but also provided powerful language and motivation for justice work. Multiracial faith communities can create spaces for reconciliation and shared purpose, though not without confronting their own historical complicity with racism. The moral frameworks offered by diverse spiritual traditions can help sustain the long-term commitment required for transformative change. Perhaps most fundamentally, building a more equitable society requires reimagining American identity itself. The mythology of white supremacy has distorted how Americans understand their national story and who counts as fully American. A more inclusive patriotism would celebrate America's diverse peoples and cultures while acknowledging historical injustices. It would recognize that loving one's country means working to help it live up to its highest ideals rather than denying its failings. Progress toward racial equity will never follow a straight path. Periods of advancement will continue to face backlash and resistance. The work spans generations, with each doing its part in an unfinished journey. Yet history offers hope through examples of seemingly immovable systems that eventually gave way to organized resistance and moral courage. The task for Americans today is to learn from both the successes and failures of earlier struggles, adapting their lessons to contemporary challenges while maintaining the long view necessary for transformative change.

Summary

America's struggle with white supremacy represents the central contradiction in its national story—a nation founded on ideals of freedom and equality while practicing enslavement and segregation. This fundamental tension has shaped every aspect of American life, from politics and economics to culture and personal identity. White supremacy has never been merely about individual prejudice but about interlocking systems that distribute power, resources, and opportunity along racial lines. These systems have proved remarkably adaptable, evolving from slavery to Jim Crow to more subtle but still powerful forms of discrimination. Throughout this history, resistance has been constant, with each generation developing strategies appropriate to their time while building on previous struggles. Moving forward requires both unflinching honesty about the past and committed action in the present. Americans must recognize how deeply white supremacy has shaped their institutions without falling into fatalism about the possibility of change. This means rejecting both comforting myths about racial progress and cynicism about the potential for transformation. It means building coalitions across racial lines while centering the voices and leadership of those most affected by ongoing injustice. It means connecting personal growth to structural change, understanding that neither is sufficient alone. Most fundamentally, it requires reimagining American identity itself—not as a hierarchy with some groups more truly "American" than others, but as a pluralistic democracy where full belonging is everyone's birthright. This work is not separate from America's founding promise but essential to its fulfillment.

Best Quote

“I had an opportunity to know, and this is what I chose to believe. I had an opportunity to speak, and this is what I chose to say. I had an opportunity to act, and this is what I chose to do.” ― Don Lemon, This Is the Fire: What I Say to My Friends About Racism

Review Summary

Strengths: The review praises Don Lemon's eloquent prose and the compelling flow of his writing. The reviewer appreciates Lemon's ability to address significant social issues, such as racism, with sincerity and depth, drawing comparisons to James Baldwin. The personal anecdotes, including reflections on family and personal loss, add a poignant and relatable dimension to the book.\nOverall Sentiment: Enthusiastic\nKey Takeaway: The review highlights the book as a powerful and eloquent exploration of America's persistent racism, enriched by personal narratives and a call for awareness and change. The reviewer finds Lemon's writing both engaging and thought-provoking, offering a glimmer of hope amidst the challenges.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.