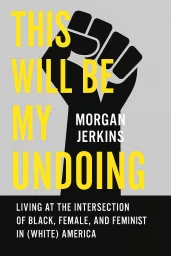

This Will Be My Undoing

Living at the Intersection of Black, Female, and Feminist in (White) America

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, Memoir, Audiobook, Feminism, Essays, Social Justice, African American, Race, Anti Racist

Content Type

Book

Binding

Paperback

Year

2018

Publisher

Harper Perennial

Language

English

ASIN

0062666150

ISBN

0062666150

ISBN13

9780062666154

File Download

PDF | EPUB

This Will Be My Undoing Plot Summary

Introduction

Morgan Jerkins' journey through life as a black woman in America is a profound exploration of identity, resilience, and the complex interplay between race and gender. Born and raised in a predominantly white New Jersey suburb, Jerkins navigates the challenging terrain of American society with remarkable candor and intellectual vigor. Her experiences—from childhood encounters with racial stereotypes to her Ivy League education at Princeton and her eventual emergence as a respected voice in contemporary journalism—offer a window into the multifaceted reality of black womanhood in a society built on white supremacy. Through her personal narrative, Jerkins illuminates three critical dimensions of the black female experience in America: the psychological impact of constantly being viewed through the prism of both race and gender; the struggle to establish authentic identity in spaces where blackness is either invisible or hypervisible; and the transformative power of finding one's voice in a world that often attempts to silence it. Her reflections reveal how black women must navigate multiple forms of oppression simultaneously, creating a unique perspective that is too often marginalized in mainstream discourse. As readers accompany Jerkins through her formative experiences, they witness not just the challenges she faces, but also the intellectual and emotional strength she cultivates to transform adversity into insight.

Chapter 1: Early Identity Formation: The Cheerleader and the Monkey

When Morgan Jerkins was ten years old, the only thing she wanted was to be a white cheerleader. In her young mind, this aspiration represented a perfect ideal—bone-straight hair, thin nose, saccharine voice, and slender body. It was during the cheerleading tryouts at her elementary school that Jerkins first confronted the stark reality of racial hierarchies. As one of only four black girls among thirty white girls, she felt the overwhelming whiteness of the cafeteria where they practiced. Though she couldn't perfectly execute the jumps due to her "pudgy body" and developing breasts, she compensated with enthusiasm, hoping that proximity to these white girls would somehow transfer their desirability to her. The cheerleading experience became a pivotal moment in Jerkins' understanding of her racial identity. Despite her efforts, when the results were announced, name after name was called—all white girls hugging their white mothers. Jerkins wasn't selected. The rejection stung, but what truly illuminated the racial dimensions of her experience was a comment from a Filipina "friend" who later told her: "Do you know why you didn't make the cheerleading squad, Morgan? It's because they don't accept monkeys like you on the team." This crude racism from someone darker-skinned than herself revealed something profound about racial dynamics—no amount of practice, smiling, or performance could obscure the inescapable reality of being a black girl in America. In high school, Jerkins faced a different kind of racial tension when her family moved to Williamstown, a less diverse suburban town. There, she became the target of bullying by Jamirah, a black girl who had moved from Virginia. Jamirah would publicly mock Jerkins' neck, wardrobe, intelligence, speech, and looks. The harassment was relentless, leaving Jerkins contemplating suicide. What made this experience particularly complex was that it wasn't white racism but intra-racial conflict—black girls raging for dominance and assertion in different ways. Jerkins recognized that she and Jamirah represented two different approaches to black girlhood. While Jerkins tried to conform to respectability politics with her cardigans and plaid skirts, taking advanced placement courses, Jamirah was unapologetically loud and resistant to these norms. Jerkins secretly believed her approach—assimilation and academic achievement—would lead to success, while girls like Jamirah were destined to become statistics. Yet she also felt guilt for not defending herself more aggressively, for not embodying the strength expected of black girls. In a surprising turn, Jerkins once lost her wallet containing her phone and money, only to discover that Jamirah and her friend had turned it in to the office with everything intact. This moment complicated Jerkins' understanding of community and protection among black girls. Despite their differences and the pain Jamirah had caused, there was an unspoken code: black girls don't steal from other black girls. Shortly afterward, Jamirah complimented Jerkins on her appearance at a school dance, offering what Jerkins came to recognize as perhaps an unspoken apology. This early identity formation taught Jerkins that "belonging to the world of black women demands strength, on-your-feet wit, and aggression, because space for and by ourselves is small." She learned that black girls are fighting to exist, whether through assimilation like herself or through assertive resistance like Jamirah. The experience showed her that regardless of their different approaches, they were all battling in the "chasm between what I thought I was, what I wanted to be, and how others saw me"—a space where many black women find themselves caught.

Chapter 2: Societal Expectations: Learning Docility and Resistance

In a satirical yet piercing chapter, Jerkins explores how society systematically teaches black girls to be docile. Beginning from birth, she details how a black girl child is conditioned to be quiet, submissive, and restricted in both body and mind. From teaching girls to say "Dada" first, reinforcing that everything returns to man as the establishment, to hitting their kneecaps when their legs begin to spread, society creates a painful association between openness and punishment. Young black girls are cautioned against being "fast-tailed," a warning that their sexuality must be suppressed at all costs. This socialization continues into adulthood, where black women are taught that their worth is measured by male approval. Jerkins writes that women must "let the man be the man," allowing him to be right even when wrong. During intimate moments, a woman should "lie on her back and spread her legs as far as they can go," enduring pain in silence. If her partner cheats, she must blame herself for not keeping him satisfied. The consequences of this conditioning are devastating—women shrink until they "need a booster seat to sit at the table," their voices become so high-pitched that "no human ear can detect" what they're saying, and their bodies close up from neglect. The manifestation of these expectations became evident in Jerkins' dating life at Princeton, where black women outnumbered black men nearly three to one. Despite her academic achievements, she felt invisible to men, particularly black men. At parties, she would learn that football players had created lists of the most attractive black women on campus—lists that never included her. This invisibility made her question whether there was something intrinsically wrong with her. She wondered if her outspoken nature and provocative articles in the campus newspaper made her undesirable, as she observed that black women who had steady partners seemed "less vocal, more reserved." After graduation, Jerkins' first significant romantic interest was Bradley, a childhood friend who invited her on an all-expenses-paid trip to Nevada. Though she initially refused to have sex with him without commitment, she felt pressured to perform oral sex—not out of desire but obligation, believing her silence through this act was "my kind of docility." When Bradley later revealed he wanted to travel the world and sleep with other women despite telling Jerkins he loved her, she was devastated. This heartbreak reinforced the message that her value as a black woman was conditional. The internalization of these expectations extended to how Jerkins navigated public spaces. After moving to Harlem, she noted how she responded to male attention, developing an addiction to being seen as beautiful or desirable. Street harassment became normalized, and she found herself unable to say "no" outright to men who approached her, instead using excuses or smiling to soften rejections out of fear for her safety. Jerkins observed that "as a black woman, if you are not acknowledged at all, even in the most vulgar of ways, then do you still have a body?" Perhaps most troubling was how these societal expectations infiltrated Jerkins' most private thoughts. When she began exploring her sexuality through pornography, she discovered her fantasies often involved unequal power dynamics—herself as subordinate to men in positions of authority. She realized these fantasies "ran opposite to my desire that I be loved fully and treated respectfully," yet they revealed the "darkest truth about myself: I couldn't see how genuine, healthy love could be associated with sex because sex seemed all about power and I had none of it even without taking my clothes off."

Chapter 3: Body and Sexuality: The Complex Journey of Self-Acceptance

Morgan Jerkins' relationship with her body and sexuality was deeply influenced by cultural expectations imposed on black women. From a young age, she received complex messages about black female bodies. When she was three, her mother's friends applied a chemical hair relaxer—the "creamy crack"—to her thick afro. Despite the burning sensation that made her cry, this began a decade-long tradition of chemically straightening her hair. Through this painful ritual, she internalized the message that her natural hair was unacceptable, that beauty required conformity to white standards that privileged bone-straight hair over natural texture. The linguistic framing of black women's hair reveals much about societal attitudes. In the 1700s, black women's hair was categorized as "wool," immediately suggesting they were more animal than human. Terms like "nappy," "kinky," and "shag" carry both sexual and violent implications. Jerkins notes that this cultural scripting around black women's hair represents more than aesthetic preference—it's about control and dehumanization. Throughout history, black women's hair has been regulated, from the tignon laws of 1786 that forced women of African descent to cover their heads, to modern dress codes that ban natural hairstyles like afro-puffs and dreadlocks as "distracting" or "unprofessional." Her body image struggles extended beyond hair. At ten, Jerkins was slapped on the butt by male classmates as part of their competitive game targeting Black and Latina girls. These early sexualized experiences taught her that her body was public territory, reinforcing the concept of the "fast-tailed girl"—a term used to shame black girls who were perceived as too sexual. This label, Jerkins argues, both attempts to protect black girls in a world that hypersexualizes them and simultaneously denies them the innocence afforded to white girls. Perhaps the most intimate bodily struggle Jerkins describes involved her left inner labium, which protruded approximately four centimeters from her body. What she called her "second tongue" caused physical pain when it chafed against clothing, especially in hot weather. Yet she hesitated to pursue labiaplasty, concerned that modifying her body would make her "less of a feminist." She wondered if she was merely succumbing to patriarchal beauty standards rather than addressing genuine physical discomfort. When Jerkins finally underwent the procedure at age 23, she faced psychological hurdles that surprised her. The doctor and nurse discussed her body as if she weren't present, and afterward, she experienced disturbing dreams about sexual assault focused on her surgical stitches being torn. She felt disconnected from her sexuality, noting that "I had never been penetrated or given birth to a child. A vagina that, for lack of a better word, had not been used." The experience left her questioning how much of her decision was about physical comfort versus societal expectations. Throughout these bodily experiences, Jerkins recognized the double bind facing black women: their bodies are simultaneously hypervisible and unseen. When she decided to wear her hair natural after years of chemical straightening, she experienced a sense of liberation. Standing in front of the mirror, seeing her skin, large afro, and curvy frame, she came to a realization: "The black female imaginary is what happens when you look at yourself, when your body is what you hold on to and your mind focuses inward to inquire about who you are, not outward to actively combat what is out there." This journey toward self-acceptance required rejecting the white gaze that had defined her relationship with her body. Jerkins concluded that if her natural hair is considered wild, "so be it. I prefer it that way." Her sexuality, once a source of shame, became "harnessed through black women's manes" as something institutions try to tame but cannot. Her body, once a battleground of conformity versus authenticity, became "a provocation" and a source of power—a stance that required rejecting both external judgment and internalized shame.

Chapter 4: Finding Voice in White Spaces: Language and Cultural Navigation

When Morgan Jerkins traveled to St. Petersburg, Russia, for a summer language program, she experienced an illuminating shift in her identity. As the only black person in her program, she constantly felt the weight of white gazes. Russians would stare at her "unblinkingly for close to a minute with an intensity I will never forget." Unlike the subtle racism she knew in America, these stares were unflinching, making her feel perpetually surveilled. This constant scrutiny made her hesitant to ride the metro alone, as she felt vulnerable in a way her white classmates could never understand. The most harrowing experience came when Jerkins and her classmates went to a bar where they encountered neo-Nazis. When one man proudly declared, "Do you know what I am? I'm skinhead," Jerkins immediately fled, dragging her intoxicated Mexican-American friend with her. Later, when her white Scottish classmates joined them, they recounted how they had joined the Nazis in saluting—claiming they did so out of fear, though their giggles suggested otherwise. Jerkins realized that for them, this encounter was just "another raucous night," a story to tell, while for her it represented genuine danger from which she could not escape by virtue of her blackness. This experience mirrored Jerkins' broader struggle with language and cultural navigation in predominately white spaces. At Princeton, she studied Japanese, drawn to the language after childhood fascination with Sailor Moon. During her internship at Temple University Japan, she found a form of liberation in being seen primarily as a foreigner rather than specifically as a black woman. She reflected, "I was not in a country where my ancestors had been enslaved. I was not stared at when I walked through different neighborhoods... no one made any snide remarks about my body, and I never heard a racial slur. In short, I was free." However, this freedom was shattered when she learned that George Zimmerman had been acquitted for killing Trayvon Martin. Suddenly, America's racial reality intruded into her Japanese escape. Though physically distant from the collective mourning of Black Americans, she felt deeply connected to this pain. She realized that her multilingualism and education couldn't shield her from the realities of being black in America: "I was a fraud, pretending that my education and multilingualism would somehow protect me from the ever-revolving cycle of black death." When Jerkins moved to Harlem, she faced another complex cultural navigation—feeling like an outsider in a predominantly black space. Having been raised in majority-white environments, she struggled to understand the communal nature of Harlem's streets. She pathologized expressions of black identity that didn't conform to white standards—the loud conversations, the street vendors, the religious declarations on subway cars. She admitted, "I felt closer to my white, gay, Republican roommate than anyone else," until she realized she was applying white behavioral standards to black cultural expressions. This realization came to a head during a lunch at the home of a Polish academic supporter, when her host's uncle asked her, "Why would you want to call yourself black? Why not just call yourself a human?" Jerkins recognized that white people's claim that they "don't see race" actually requires black people to shed their identities. She responded, "I call myself a black woman because that's what I am. I can be both a black woman and a human. Those identities aren't separate from each other." Through these experiences across different cultural contexts, Jerkins came to understand that her blackness wasn't something to transcend or escape. "I call myself black because that is who I am," she concluded. "Blackness is a label that I do not have a choice in rejecting as long as systemic barriers exist in this country. But also, my blackness is an honor, and as long as I continue to live, I will always esteem it as such."

Chapter 5: The Power of Community: Black Women Supporting Each Other

In an eloquent open letter addressed to former First Lady Michelle Obama, Jerkins explores the profound impact of seeing a black woman achieve unprecedented prominence in American public life. She recalls the infamous 2008 New Yorker cover that portrayed the Obamas as terrorists, noting how Michelle's image was particularly distorted—her hair transformed into a large afro resembling "barbed wire," her lips painted red to accentuate their fullness, her body language exaggerated to fit stereotypes of the "sassy black woman." This caricature revealed how white America often viewed powerful black women through a lens of fear and distortion. Despite these hostile depictions, Michelle Obama's ascendance represented something revolutionary. Jerkins traces Michelle's lineage back to her great-great-grandfather Jim Robinson, born on Friendfield Plantation in South Carolina—over 450 miles from the White House where she would later reside. This trajectory from plantation to Pennsylvania Avenue embodied a kind of "intergenerational revenge" that disrupted America's racial hierarchy. Unlike Barack, Michelle could not claim a white parent; her blackness was undiluted and undeniable. Her excellence—Princeton and Harvard Law degrees, successful legal career—couldn't be attributed to anything but her own brilliance. For Jerkins and other black female students at Princeton, Michelle became an almost biblical figure of inspiration. When Jerkins struggled with dating and relationships at Princeton, where black women outnumbered black men three to one, Michelle's story provided hope—she was proof that a brilliant black woman could excel professionally and find love with someone who celebrated rather than diminished her. Michelle showed that one didn't have to choose between professional success and personal fulfillment, defying the stereotype of the perpetually single, high-achieving black woman. The concept of black female solidarity extends beyond Michelle Obama in Jerkins' narrative. She explores the phenomenon of "Black Girl Magic," a movement celebrating black female excellence and accomplishment. However, this concept is not without complexity. When Harvard scholar Dr. Linda Chavers criticized the term for potentially reinforcing the "Strong Black Woman" stereotype that denies black women's vulnerability, Jerkins initially joined the backlash. Yet upon further reflection, she recognized that Chavers—a black woman with multiple sclerosis—was highlighting how the movement often centered able-bodied black women, inadvertently marginalizing disabled black women. This realization made Jerkins question the accessibility of "Black Girl Magic" to all black women. She noted that "physically disabled black women are virtually invisible in our cultural landscape" and rarely celebrated in the same way as able-bodied black women. The labor force participation rate for black women with disabilities (22.2%) lagged significantly behind that of white women with disabilities (29%), with black disabled women having the lowest income among all race/gender disability categories. Jerkins concluded that true solidarity must include all black women, not just those who fit certain physical or social paradigms. Personal experiences of community appear throughout Jerkins' narrative, from the black women at Princeton who rallied around her after anonymous racist comments on her newspaper column, to Irie Thomas, a prophetess from her church who accurately predicted when Jerkins would hear from Princeton after being waitlisted. These moments of support and supernatural connection to other black women provided Jerkins with crucial affirmation during times of doubt and rejection. They demonstrated how black women's community functions as both practical support system and spiritual sustenance—a powerful counterforce to a society that consistently undervalues black women.

Chapter 6: Creating Authentic Art: Writing Black Female Experiences

For Jerkins, the question of who gets to tell black women's stories is not merely academic—it's deeply personal and political. She analyzes the French film "Girlhood" (Bande de filles), which portrays the lives of poor black French girls in a Paris suburb. While praising the film's artistic merits, Jerkins questions white director Céline Sciamma's authority to tell this story. When interviewed, Sciamma claimed, "I'm making this universal... It's not about race. It's not about struggling with racism." This comment troubled Jerkins, as it erased the specific racial dimensions of black girlhood. Sciamma further justified her choice by saying, "I had a strong sense of having lived on the outskirts even if I am a middle-class white girl," a comparison Jerkins found deeply problematic. This appropriation of black women's narratives extends beyond film into literature and criticism. Jerkins notes that film reviews of "Girlhood" were predominantly written by white male critics or non-black women of color, with black women's perspectives largely absent. She questions whether nonblack women of color conflating black women's experiences with their own under the umbrella term "brown" dilutes the specificity of black women's struggles. Fanta Sylla, a black French writer, argued that this terminology can function as "a euphemism... It feels more like a trap than an identity to me." When Beyoncé released her visual album "Lemonade" in 2016, Jerkins saw a powerful contrast—a black female narrative created by and centered on black women. Unlike "Girlhood," which claimed universality while erasing racial specificity, "Lemonade" asked explicitly, "What is it like to be a black woman in America?" and answered through undiluted black female imagery and experiences. Beyoncé allowed black women to "remain at the center" without white presence to provide "momentary relief." The film celebrated plurality among black women, showing that they "are not one thing" while still affirming their shared experiences and need for community. For Jerkins, authentic representation of black female experiences must include acknowledging both pain and joy, both trauma and resilience. She critiques how slavery narratives often focus exclusively on victimization, erasing slaves' intelligence, humor, and resistance. When a children's book showing smiling enslaved people cooking for George Washington was published and subsequently pulled, Jerkins wondered if the controversy missed something important: "To erase the wit and comedy of slaves, their ability to laugh, is almost as serious a crime as erasing the abuses they suffered: both strip them of their humanity." This balance between acknowledging trauma and celebrating resistance shapes Jerkins' approach to her own writing. She describes how slaves used the "cakewalk" dance to mock their masters' stiff movements, creating a form of satire that white people mistook for flattery. Similarly, black people developed "signifying" language that white people couldn't fully comprehend—creating space for critique and community that existed beyond white surveillance. These historical strategies of resistance through art and language continue to inform black women's creative expression today. The question of who should write about black women remains complex for Jerkins. She acknowledges that non-black writers can write about black women, but believes they must "self-interrogate while they write about black women and... dismiss universality, color blindness, or dilution of any kind." More importantly, she insists that black women themselves must be at the center of telling their own stories, not as tokens but as authentic voices with the full range of human experience. As she concludes, "My idea of a black narrative is one that subverts, flips, and undermines rule until that final product cannot be duplicated by anyone other than one with black hands."

Chapter 7: Survival and Healing: A Manifesto for Black Women

In her powerful concluding manifesto, Jerkins creates a survival guide for black women living in a society that often seeks to diminish them. She begins with self-affirmation: "When you wake up in the morning, thank God, the Universe, or the ancestors that you have been able to see another day." This recognition that survival itself is "a triumph" establishes the foundation for black women's resistance. Before stepping into a world that will attempt to define and diminish them, Jerkins urges black women to first recognize their own reflection and beauty, to "submerge yourself in your beauty. Do not question. Do not filter. Do not judge." Jerkins confronts the reality that black women's bodies are constantly scrutinized and judged regardless of their choices. "No matter which article of clothing you place over your body, you will have someone think of you as a slut," she writes, acknowledging that this judgment "is not your fault" but rather "an injustice that has been tailor-made for black women." Rather than succumbing to these judgments, she encourages black women to wear what makes them feel good, because "what others think of you is none of your concern." Throughout the manifesto, Jerkins repeatedly affirms, "You are not paranoid," validating black women's experiences of discrimination that are often dismissed. From people who compliment black women on their "eloquence" only because they adhere to white norms, to strangers who reach for black women's hair without permission, to subtle workplace discrimination—these experiences are real, not imagined. This validation is crucial because society often gaslights black women, making them question their own perceptions of racism and sexism. Community is essential to survival, Jerkins emphasizes. When black women dance together "on beat without any instruction, this is not coincidence. This is solidarity." Even when physically separated, black women remain connected: "There is another who is experiencing this same kind of lack... There is a cosmic wavelength of our universal spirit." These connections provide strength when individual resources are depleted. While community is vital, Jerkins also champions self-care and boundaries. "You do not owe anyone anything," she insists, giving black women permission to rest and refuse others' demands. "You are not a mule," she writes, rejecting the historical burden placed on black women to carry everyone else's problems. Even involvement in social justice movements must be balanced with self-preservation: "The revolution is ongoing... But you will be unprepared for the task if you run yourself ragged." Jerkins addresses black women's sexuality with tenderness and power. "When you make love, nakedness does not begin after your clothes are strewn across the floor. Nakedness begins when you strip every shameful memory about your body before penetration." She reframes sexuality not as something dirty or forbidden, but as connection to something ancient and powerful: "You are the start of civilization, and lovemaking is the pledge of allegiance to all that you are." The manifesto concludes with intergenerational healing, encouraging black women to "forgive your mothers and grandmothers" while recognizing that this is an individual choice. For those who become mothers, she advises against obsessing over a daughter's appearance—concerns about skin color and hair texture are "legitimate" given social hierarchies, but should not overshadow "the excitement that you are bringing life into this world." Ultimately, Jerkins' manifesto offers both practical strategies for survival and spiritual affirmation of black women's inherent value. Her final guidance brings the journey full circle: "When you lie down in bed, turn your face towards the window to allow for the moon to kiss you on the forehead with its light... Whatever happened during the day is done. But you are still here and should revel in that, for this is how you survive."

Summary

Morgan Jerkins' exploration of black womanhood in America reveals how identity forms at the intersection of race and gender, creating experiences that are simultaneously universal and specific. From her childhood desire to be a white cheerleader to her adult navigation of predominantly white professional spaces, Jerkins illuminates how black women must constantly negotiate between authenticity and survival. Her journey through self-acceptance—embracing her natural hair, understanding her sexuality, finding her voice as a writer—demonstrates the revolutionary potential of black women who refuse to diminish themselves to fit into narrow societal expectations. The most profound insight emerging from Jerkins' narrative is that black women's liberation comes not from erasing their blackness to achieve some false universality, but from embracing the fullness of their specific experiences. When she writes, "I call myself black because that is who I am. Blackness is a label that I do not have a choice in rejecting as long as systemic barriers exist in this country. But also, my blackness is an honor," she offers a transformative perspective. For anyone navigating their own complex identities, Jerkins provides a blueprint for authenticity: acknowledge both pain and joy, embrace community while setting boundaries, and recognize that true freedom comes not from transcending identity but from claiming it fully, with all its complexities and contradictions.

Best Quote

“We cannot come together if we do not recognize our differences first. These differences are best articulated when women of color occupy the center of the discourse while white women remain silent, actively listen, and do not try to reinforce supremacy by inserting themselves in the middle of the discussion.” ― Morgan Jerkins, This Will Be My Undoing: Living at the Intersection of Black, Female, and Feminist in (White) America

Review Summary

Strengths: The review acknowledges Morgan Jerkins's "prodigious intellect and curiosity" and describes her as a "deft cartographer of black girlhood and womanhood." It highlights her ability to weave personal, public, and political themes in a compelling manner, and notes her presence as a significant new writer.\nWeaknesses: The reviewer criticizes the book for being "horrible" and "confusing," lacking flow, and failing to deliver a satisfying narrative or resolution. They express difficulty relating to the content and question the authenticity of the author's journey to peace, describing it as a "screeching halt."\nOverall Sentiment: Mixed. While the review opens with praise for Jerkins's intellect and thematic exploration, it quickly shifts to a critical tone, expressing dissatisfaction with the book's structure and emotional impact.\nKey Takeaway: The review presents a dichotomy between recognizing Jerkins's intellectual prowess and thematic intentions, and a personal disappointment with the book's execution and emotional resonance.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.