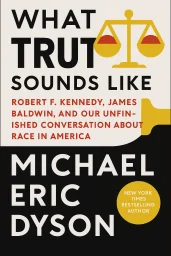

What Truth Sounds Like

Robert F. Kennedy, James Baldwin, and Our Unfinished Conversation About Race in America

Categories

Nonfiction, History, Politics, Audiobook, Sociology, Social Justice, African American, American History, Race, Anti Racist

Content Type

Book

Binding

Kindle Edition

Year

2018

Publisher

St. Martin's Press

Language

English

ASIN

B076ZRB4CG

ISBN13

9781250199423

File Download

PDF | EPUB

What Truth Sounds Like Plot Summary

Introduction

In 1963, a pivotal yet contentious meeting took place between Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and a group of Black intellectuals, artists, and activists led by James Baldwin. This encounter revealed profound tensions between political pragmatism and the lived experience of racial oppression in America. What began as Kennedy's attempt to understand racial unrest in northern cities evolved into a confrontation about the fundamental nature of American democracy and the chasm between white liberal understanding and Black reality. The exchange exemplified two competing approaches to racial justice: Kennedy's focus on incremental policy solutions versus Baldwin's insistence on moral witness and authentic testimony about Black suffering. This tension between policy and witness, between institutional change and personal transformation, continues to shape racial discourse in America today. The conversation that began in that New York apartment remains unfinished, as contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter echo Baldwin's demand for both substantive policy change and moral reckoning. By examining this historical encounter and its aftermath, we gain crucial insight into why racial progress remains so elusive in American society, and why true democracy requires both political action and the willingness to hear uncomfortable truths. The clash of perspectives that unfolded in that room offers a framework for understanding the complex dynamics that continue to shape America's racial landscape.

Chapter 1: The Historic Meeting: Baldwin, Kennedy, and the Clash of Perspectives

On May 24, 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy invited James Baldwin to gather a group of Black intellectuals and artists for a discussion about race relations in America. This meeting, held at Kennedy's father's Manhattan apartment, came at a time of heightened racial tension. The Birmingham movement had recently captured national attention with images of police dogs and fire hoses being turned on peaceful protesters, including children. The Kennedy administration was struggling to balance civil rights demands against political considerations, particularly concerns about alienating white Southern Democrats. Baldwin assembled an impressive group, including singer Harry Belafonte, playwright Lorraine Hansberry, psychologist Kenneth Clark, and singer Lena Horne. Most critically, Baldwin invited Jerome Smith, a young Freedom Rider who had been brutally beaten during civil rights protests in the South. Kennedy entered the meeting expecting a productive discussion about urban racial issues. Instead, he encountered raw emotion and unfiltered truth about the Black experience in America. When Kennedy asked Smith if he would fight for his country, Smith replied that he would never take up arms for America while it continued to oppress Black citizens. This response stunned Kennedy, who came from a family with a strong tradition of military service. The meeting quickly deteriorated as Kennedy's attempts to highlight his administration's civil rights efforts were met with skepticism and anger. The assembled Black voices refused to moderate their testimony or acknowledge Kennedy's political constraints. When Baldwin suggested that President Kennedy should personally escort Black students to desegregated schools, Robert Kennedy dismissed the idea as "phony" and impractical. The exchange revealed a fundamental disconnect: Kennedy viewed racial problems through a pragmatic political lens, while Baldwin and his companions insisted on moral witness and authentic recognition of Black suffering. Baldwin later reflected that Kennedy "didn't understand what we were trying to tell him...For him it was a political matter...But what was wrong in this case turned out to be something very sinister, very deep, that couldn't be solved in the usual way." The meeting ended without resolution, with Kennedy feeling attacked and the Black participants feeling unheard. Kennedy reportedly called Baldwin a "nut" afterward, and the FBI increased surveillance on several participants. Yet this contentious exchange would prove transformative for Kennedy, planting seeds that would eventually change his perspective on race in America. Despite its apparent failure, the meeting represented a pivotal moment in America's racial discourse. It highlighted the gap between white liberal understanding and Black lived experience, between policy solutions and the need for moral reckoning. The dynamics that played out in that room - the tension between political pragmatism and authentic witness - continue to shape America's ongoing struggle with race and democracy.

Chapter 2: Witness vs Policy: Competing Approaches to Racial Justice

The Kennedy-Baldwin meeting revealed a fundamental tension in approaches to racial justice that persists today. Kennedy entered the room prioritizing policy - concrete legislative and administrative actions that could address specific racial inequities. He believed in gradual, institutional change within existing political frameworks. Kennedy's approach represented a liberal pragmatism that focused on what was politically possible rather than morally imperative. This reflected his position as a government official responsible for balancing competing interests in a divided nation. In stark contrast, Baldwin and his companions insisted on witness - the authentic expression of Black experience and suffering that demanded moral recognition before policy solutions. They understood that policy without acknowledgment of fundamental human dignity would ultimately fail. Jerome Smith's emotional testimony about police brutality and his refusal to fight for a country that oppressed him exemplified this approach. Smith insisted that Kennedy first see and acknowledge the trauma inflicted on Black Americans before attempting to solve "problems" that Kennedy had not fully comprehended. The methodological divide went deeper than strategy. It reflected different understandings of America itself. For Kennedy, racism represented a deviation from American ideals that could be corrected through better policies and laws. For Baldwin, racism was woven into the very fabric of American society, requiring a more profound transformation of national identity and consciousness. Baldwin insisted that white Americans confront their own complicity in systems of oppression before meaningful change could occur. This was not merely about changing laws but about changing hearts and minds. This tension between policy and witness continues to shape approaches to racial justice today. When contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter focus on personal testimony and emotional truth, they echo Baldwin's insistence on witness. When they demand specific policy changes to address police violence or economic inequality, they acknowledge Kennedy's focus on concrete reforms. The most effective racial justice work typically combines both approaches, recognizing that institutional change requires both moral clarity and practical action. The Baldwin-Kennedy encounter teaches us that racial progress demands both policy innovation and personal transformation. Policy without witness risks addressing symptoms rather than causes, implementing technical fixes without moral understanding. Witness without policy risks emotional catharsis without structural change. The unfinished conversation between these approaches represents the ongoing challenge of American democracy - how to translate moral recognition into effective action, how to balance idealism with pragmatism in the pursuit of justice.

Chapter 3: Artists as Truth-Tellers: Black Expression and Cultural Resistance

Black artists have historically shouldered a unique burden of representation. Unlike their white counterparts, Black artists rarely enjoy the luxury of creating "art for art's sake." Their work inevitably becomes interpreted through racial lenses, scrutinized both as individual expression and as representative of collective Black experience. This dynamic was clearly visible in Kennedy's meeting, where artists like Baldwin, Belafonte, and Hansberry functioned as cultural ambassadors and truth-tellers for the broader Black community. James Baldwin exemplified the artist as witness to uncomfortable truths. His essays and novels explored the psychological damage inflicted by white supremacy while insisting on the full humanity of Black Americans. Baldwin understood that artistic expression could convey truths that statistical studies or policy papers could not capture. When he wrote that "to be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time," he articulated an emotional reality that many white Americans, including Kennedy, struggled to comprehend. Baldwin's genius lay in transforming this rage into eloquent prose that forced readers to confront the moral contradictions of American democracy. Harry Belafonte represented another model of artistic resistance. As a globally famous entertainer, Belafonte leveraged his celebrity to advance civil rights causes, raising funds, organizing events, and serving as a crucial link between artists and activists. Belafonte understood that cultural representation matters - his careful selection of roles and musical repertoire aimed to counter degrading stereotypes of Black people. Yet he refused to separate his artistic career from political engagement, recognizing that his platform gave him both opportunity and responsibility to speak for those without voice. Lorraine Hansberry brought another crucial perspective as a Black woman playwright. Her groundbreaking work "A Raisin in the Sun" explored the intersection of race, class, and gender through the intimate portrayal of a Black family's struggles and aspirations. At the Kennedy meeting, Hansberry powerfully redirected attention to the specific suffering of Black women when she spoke of a photograph showing a white police officer standing on a Black woman's neck in Birmingham. This intervention highlighted how artistic vision could illuminate dimensions of oppression that often remained invisible in male-dominated civil rights discourse. The artists at Kennedy's meeting demonstrated how cultural expression functions as a form of resistance. They used their creative gifts to bear witness to realities that mainstream America preferred to ignore. Their presence in that room represented a refusal to separate aesthetic concerns from political engagement. They understood that art could create spaces for truth-telling when conventional political discourse failed. This tradition continues today through figures like filmmaker Jordan Peele, whose work explores racial anxieties through the lens of horror, or musician Kendrick Lamar, whose lyrics document the ongoing trauma of structural racism. The Kennedy-Baldwin meeting reminds us that artists play an essential role in democratic discourse, particularly around race. By translating lived experience into cultural forms that evoke emotional response, artists can bridge divides of understanding that political rhetoric alone cannot cross. In a society where racism operates not just through laws but through cultural narratives, artistic truth-telling remains a crucial form of resistance and democratic participation.

Chapter 4: Intellectuals and Activism: The Burden of Black Representation

Black intellectuals face distinctive challenges in American public discourse. They must balance scholarly rigor with political relevance, navigate tensions between academic institutions and community accountability, and confront expectations to "represent" Black America while maintaining intellectual independence. The intellectuals at Kennedy's meeting - particularly Kenneth Clark, whose psychological research on racial self-perception had informed the Brown v. Board of Education decision - exemplified these tensions. When Kennedy dismissed the emotional testimony of Baldwin's group as "hysteria" and suggested they lacked understanding of policy specifics, he revealed a common misconception about Black intellectual work. Kennedy preferred what he called "reasonable, responsible, mature representatives of the black community" with whom he could discuss policy in detached, technical terms. This perspective failed to recognize that the most incisive Black intellectual analysis often emerges from intimate engagement with lived experience rather than detached observation. Baldwin, though lacking formal academic credentials, demonstrated profound intellectual insight precisely because he refused to separate analysis from emotional truth. Kenneth Clark's presence at the meeting highlighted another dimension of Black intellectual labor. Clark had devoted his scholarly career to documenting the psychological damage inflicted by segregation, producing empirical evidence that proved crucial in legal battles against Jim Crow. Yet at the Kennedy meeting, Clark found himself marginalized when raw testimony from Jerome Smith proved more compelling than academic research. This illustrated the complex position of Black scholars, whose specialized expertise can sometimes seem removed from the immediate urgency of racial struggle, yet whose work provides essential foundations for political action. The meeting also revealed divergent views about the proper relationship between intellectuals and activism. Some participants believed intellectuals should provide analytical frameworks and strategic guidance for movements while maintaining critical distance. Others insisted intellectuals must be fully immersed in struggle, risking their professional standing and personal comfort in direct confrontation with power. This tension continues to animate debates within Black intellectual communities today, as scholars navigate institutional pressures toward "objectivity" while remaining accountable to communities experiencing ongoing injustice. The Black intellectual tradition represented in that room had always connected theoretical insight with practical action. From W.E.B. Du Bois to contemporary figures like Kimberlé Crenshaw, Black thinkers have developed analytical frameworks that both explain oppression and guide resistance. The distinctive contribution of this tradition lies in its refusal to separate intellectual rigor from moral clarity or theoretical sophistication from practical relevance. Black intellectual work at its best combines critical analysis with prophetic witness, identifying both immediate injustices and their deeper structural roots. Kennedy's meeting demonstrated why democratic societies need engaged intellectuals who can translate between different forms of knowledge - connecting personal testimony with systematic analysis, linking immediate grievances to historical patterns, and building bridges between specialized expertise and common understanding. The ongoing challenge for Black intellectuals remains how to speak truth to power while creating spaces for multiple voices and perspectives within Black communities themselves.

Chapter 5: Politics and Whiteness: The State's Relationship with Black America

The Kennedy-Baldwin meeting exposed fundamental tensions in the relationship between the American state and Black citizens. As Attorney General, Robert Kennedy represented the federal government's authority and power. Yet for Baldwin and his companions, this same government had historically functioned as an instrument of racial oppression rather than protection. This contradiction lies at the heart of Black Americans' ambivalent relationship with the state - simultaneously seeking its protection while remaining skeptical of its intentions. Kennedy's defensive response to criticism revealed the often invisible assumptions of whiteness embedded in American political institutions. When he argued that his family's immigrant experience proved anyone could succeed in America through hard work, Kennedy failed to recognize the fundamental difference between voluntary immigration and forced enslavement, between ethnic prejudice and racial caste. His insistence that Black Americans should be grateful for incremental progress reflected a common white liberal perspective that frames racial justice as charitable benevolence rather than basic democratic obligation. Baldwin understood that whiteness functioned not merely as racial identity but as political structure. "The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line," W.E.B. Du Bois had written, but Baldwin recognized that this line was maintained through political institutions that appeared neutral while serving white interests. When Baldwin argued that "white is a metaphor for power," he identified how American democracy had been constructed around an unacknowledged racial center. Kennedy's discomfort with this analysis reflected the difficulty many white Americans have in seeing how whiteness shapes political perception. The meeting highlighted a fundamental disagreement about the state's responsibility regarding racial justice. Kennedy viewed racial progress as something to be carefully managed within existing political constraints, balancing competing interests and maintaining electoral coalitions. Baldwin insisted that the state had a moral obligation to prioritize justice over political calculation, to risk political capital in defense of fundamental rights. This tension between pragmatic governance and moral imperative continues to shape debates about racial policy today. Jerome Smith's powerful rejection of military service illuminated the contradiction in asking Black citizens to defend a democracy that failed to protect them. His statement that he would never fight for America while it oppressed Black people challenged the state's assumption of unquestioned loyalty. Kennedy, whose brothers had served in war, found this position incomprehensible. Yet Smith was articulating a profound political insight: that legitimate democratic authority must be earned through justice rather than assumed through nationalism. The confrontation between Kennedy and Baldwin's group foreshadowed contemporary debates about the relationship between race and democracy. When movements like Black Lives Matter challenge police violence, they are not merely seeking policy reforms but questioning the legitimacy of state power that operates differently across racial lines. The unfinished conversation from that New York apartment continues as Americans struggle to reconcile democratic ideals with the persistent reality of racial inequality in political representation, public policy, and state protection.

Chapter 6: Contemporary Voices: Athletes and Activists Speaking Truth to Power

The tradition of Black witness embodied by Baldwin and his contemporaries continues through modern figures who use their platforms to challenge racial injustice. Contemporary athletes like Colin Kaepernick and LeBron James echo Muhammad Ali's legacy of speaking truth to power from positions of cultural prominence. When Kaepernick knelt during the national anthem to protest police violence, he faced many of the same accusations of unpatriotic behavior that were hurled at Ali when he refused military service. The visceral white backlash to these protests reveals how threatening Black witness remains to established power structures. The Black Lives Matter movement has revitalized Baldwin's insistence on bearing witness to racial trauma. Founded by three Black women - Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi - BLM began as a hashtag following George Zimmerman's acquittal for killing Trayvon Martin. It evolved into a decentralized movement combining direct action with sophisticated policy advocacy. Like Baldwin's group confronting Kennedy, BLM activists have refused to moderate their testimony to make white audiences comfortable. Their insistence that America face the reality of police violence against Black bodies continues the tradition of witness as democratic practice. Digital media has transformed how witness functions in contemporary racial discourse. Smartphone videos documenting police violence provide visual testimony that makes denial more difficult, though not impossible. Social media platforms allow marginalized voices to circumvent traditional gatekeepers and speak directly to public audiences. Yet these technologies also create new vulnerabilities, as Black activists face online harassment and surveillance reminiscent of the FBI monitoring that targeted Baldwin and his contemporaries. Contemporary artists continue to use cultural expression as a form of witness. Filmmaker Jordan Peele's "Get Out" uses horror conventions to expose the persistent exploitation of Black bodies. Musicians like Kendrick Lamar and Beyoncé create complex works addressing racial trauma and resilience. Writer Ta-Nehisi Coates explicitly invokes Baldwin's legacy in his explorations of American racial mythology. These cultural workers understand, as Baldwin did, that artistic expression can communicate truths about racial experience that elude conventional political discourse. The tension between policy and witness that animated the Kennedy-Baldwin meeting persists in contemporary movements. Many activists argue that true progress requires both institutional change and moral transformation. The Movement for Black Lives platform combines specific policy demands with broader calls for acknowledgment of historical harms. This dual approach recognizes that legal reform without moral reckoning ultimately preserves rather than transforms systems of power. Contemporary racial justice work faces many of the same challenges that confronted Baldwin's generation. White fragility still creates defensive responses to Black testimony. Policy makers still seek comfortable compromises that address symptoms rather than causes. Yet there is also growing recognition that America's democratic promise remains unfulfilled without honest confrontation with racial injustice. The conversation that began in that New York apartment continues as new generations find their own ways to bear witness to both enduring inequities and possibilities for transformation.

Chapter 7: From Rhetoric to Reality: Moving Beyond Symbolic Progress

The unfinished conversation between Kennedy and Baldwin illuminates why racial progress in America often feels simultaneously substantial and insufficient. Formal legal equality has advanced significantly since 1963, yet structural inequalities persist across housing, education, criminal justice, and economic opportunity. This contradiction stems partly from America's tendency to embrace rhetorical and symbolic changes while resisting deeper structural transformation. Kennedy's initial approach to civil rights exemplified this pattern - offering symbolic gestures and incremental reforms while avoiding more fundamental challenges to white power and privilege. His evolution after the meeting with Baldwin represents a more promising path. Kennedy began visiting impoverished communities, listening directly to marginalized voices, and gradually developing a more radical critique of American inequality. By 1968, when he announced his presidential candidacy, Kennedy spoke of "the disgrace of this other America" with moral clarity that echoed Baldwin's witness. His assassination cut short this journey, leaving us to wonder what might have been possible had he lived to translate this moral awakening into political action. Baldwin understood that symbolic victories, while important, could mask continuing injustice. "The price of the ticket" for Black acceptance in American society often involved accepting partial progress as sufficient achievement. Baldwin warned against premature celebration of legal victories that left economic exploitation and cultural devaluation intact. His insistence on continuing to bear witness even after formal desegregation reflected his understanding that democracy requires ongoing vigilance rather than one-time reforms. The challenge of moving from rhetoric to reality involves addressing multiple dimensions of racial injustice simultaneously. Legal equality means little without economic opportunity. Political representation loses meaning without cultural respect. Educational access fails to deliver promised mobility when schools remain segregated by race and class. Effective racial justice work must engage these interconnected systems rather than focusing on isolated reforms that leave underlying structures intact. Contemporary movements have developed increasingly sophisticated approaches to this challenge. The Movement for Black Lives platform addresses not only criminal justice reform but economic justice, political power, community control, and cultural autonomy. This comprehensive vision recognizes that racial justice requires transforming relationships between communities and institutions rather than simply integrating individuals into unchanged systems. Such approaches build on Baldwin's insight that America needs not just better policies but a fundamentally different understanding of itself. The path from rhetoric to reality also requires sustained commitment across generations. Kennedy's evolution reminds us that moral awakening must be followed by concrete action to be meaningful. Baldwin's persistence despite disappointment demonstrates the necessity of continuing to bear witness even when change seems distant. The contemporary figures who carry forward this work - from community organizers to policy advocates to cultural workers - understand that democratic transformation is a marathon rather than a sprint. The unfinished conversation between policy and witness, between institutional reform and moral transformation, continues to shape America's racial future. Moving beyond symbolic progress requires both pragmatic governance and prophetic vision, both technical expertise and moral courage. It demands willingness to hear uncomfortable truths while developing concrete strategies for change. The legacy of that fateful meeting in 1963 reminds us that true democracy emerges not from comfortable consensus but from honest confrontation with our deepest divisions and highest aspirations.

Summary

The confrontation between Robert Kennedy and James Baldwin's assembled group represents a pivotal moment in America's ongoing struggle with race and democracy. Their clash embodied a fundamental tension between two approaches to racial justice: Kennedy's focus on incremental policy solutions versus Baldwin's insistence on moral witness to Black suffering. This unresolved tension continues to shape racial discourse today, as Americans grapple with both the technical challenges of institutional reform and the moral imperative of acknowledging historical and continuing injustice. The meeting revealed how whiteness functions as an unacknowledged center of American political life, structuring perceptions and priorities in ways that remain largely invisible to those who benefit from it. Beyond its historical significance, this unfinished conversation offers crucial insight into the nature of democratic dialogue itself. True democracy requires both pragmatic governance and authentic witness, both institutional accountability and moral recognition. The evolution of both Kennedy and Baldwin after their contentious meeting suggests that meaningful change emerges not from comfortable agreement but from willingness to engage across profound differences. As contemporary movements continue to navigate the relationship between policy demands and moral testimony, between institutional change and cultural transformation, they carry forward the essential democratic work that began in that New York apartment over half a century ago. The path toward racial justice still requires both clear-eyed analysis of power structures and courageous witness to human suffering - the dual legacy of that momentous encounter between policy and witness.

Best Quote

“Maleness has functioned in our race much like whiteness has in the larger culture: its privileges have been rendered normal, its perspectives natural, its biases neutral, its ideas superior, its anger wholly justifiable, and its way of being the gift of God to the universe.” ― Michael Eric Dyson, What Truth Sounds Like: Robert F. Kennedy, James Baldwin, and Our Unfinished Conversation About Race in America

Review Summary

Strengths: The review praises Michael Eric Dyson as an incredible writer and thinker, emphasizing the importance of his voice in discussions on racism. The book is described as powerful and highly relevant, with a strong recommendation for readers, especially white people, to engage with it. The review also highlights the author's ability to address complex issues.\nWeaknesses: The reviewer notes that the book may not be liked by everyone and acknowledges occasional disagreements with the author, suggesting that the book's perspective is subjective and may not align with all readers' views.\nOverall Sentiment: Enthusiastic\nKey Takeaway: The review underscores the necessity for white America to listen to the voices of people of color to foster real change and move beyond racism, recommending Dyson's book as an essential read for understanding these issues.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.