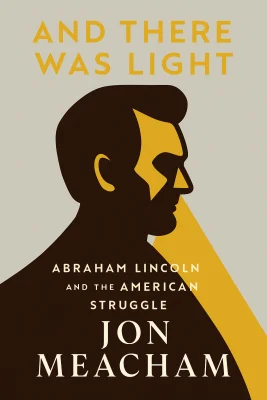

And There Was Light

Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle

Categories

Nonfiction, Biography, History, Politics, Audiobook, Biography Memoir, Historical, Presidents, American History, Civil War

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

2022

Publisher

Random House

Language

English

ASIN

0553393960

ISBN

0553393960

ISBN13

9780553393965

File Download

PDF | EPUB

And There Was Light Plot Summary

Introduction

On a cold winter's day in February 1865, Abraham Lincoln stood before a nation torn by four years of civil war to deliver his Second Inaugural Address. Rather than celebrating the Union's imminent victory, he offered a profound meditation on collective guilt and national redemption: "With malice toward none, with charity for all... let us strive to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds." This moment captured the essence of Lincoln's remarkable journey from frontier poverty to presidential greatness—a journey defined by moral growth, pragmatic wisdom, and an unwavering commitment to human freedom. Born in a humble Kentucky log cabin in 1809, Lincoln rose through self-education and determination to become America's most consequential president during its greatest crisis. His leadership during the Civil War not only preserved the Union but transformed it, ending the moral contradiction of a nation founded on liberty yet practicing slavery. Through Lincoln's life, we witness the development of a distinctive moral vision that balanced principle with pragmatism, the evolution of a leader who grew beyond the prejudices of his era, and the emergence of a political philosophy that redefined American democracy as fundamentally committed to equality and opportunity for all.

Chapter 1: Frontier Origins: Forging Character Through Adversity

Abraham Lincoln's journey began in the crude simplicity of a one-room log cabin in Hardin County, Kentucky, on February 12, 1809. Born to Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, his early years were marked by the hardship and uncertainty common to frontier life. The Lincoln family moved first to Indiana when Abraham was seven, partly to escape Kentucky's slavery system and uncertain land titles. This uprooting introduced young Lincoln to the backbreaking work of clearing wilderness and establishing a new homestead—experiences that would later authenticate his image as a self-made man who understood the dignity of physical labor. Tragedy struck early when Lincoln's mother Nancy died from "milk sickness" when he was just nine years old. This profound loss created an emotional void and contributed to the melancholy that would surface throughout his adult life. A year later, his father married Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow with three children who became a nurturing influence on young Abraham. Unlike his father, who was largely indifferent to education, Sarah encouraged Lincoln's intellectual curiosity and protected his time for reading. Lincoln would later recall, "She had been my best friend in this world." Despite receiving less than a year of formal schooling, Lincoln developed an insatiable hunger for knowledge. He would walk miles to borrow books, reading by firelight after completing his daily chores. His stepmother later remembered how he would read everything available, copying passages he found meaningful and committing them to memory. This self-education through works like the Bible, Aesop's Fables, Robinson Crusoe, and later Shakespeare and Euclid's geometry laid the foundation for his remarkable ability to express complex ideas with clarity and moral force. The harsh realities of frontier life shaped Lincoln's character in other ways. His father frequently hired him out to neighbors for manual labor, an arrangement that fostered resentment but also developed self-reliance. These early experiences exposed Lincoln to different people and perspectives, nurturing his famous empathy and storytelling abilities. A flatboat journey to New Orleans in his late teens reportedly brought him face-to-face with the brutality of slavery at a slave auction, an experience that some biographers suggest planted the seeds of his later antislavery convictions. By the time Lincoln left his father's home at twenty-one to make his own way in the world, adversity had forged the essential elements of his character: intellectual curiosity, moral sensitivity, physical resilience, and a determination to rise above his circumstances. His experiences of poverty and limited opportunity gave him a lifelong sympathy for the common man and a belief in the dignity of labor. Most importantly, these formative years instilled in Lincoln a distinctive moral perspective—one that valued self-improvement, recognized human equality beneath social differences, and maintained faith in the possibility of both personal and national progress despite setbacks and suffering.

Chapter 2: Self-Education and Moral Awakening

Abraham Lincoln's intellectual development represents one of history's most remarkable examples of self-education. Without formal schooling beyond a few scattered months, Lincoln crafted his own curriculum through voracious reading. In New Salem, Illinois, where he settled as a young man, Lincoln borrowed books from neighbors and studied by candlelight after long workdays. His reading ranged from Shakespeare and Burns to Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England, which he mastered while working as a store clerk. This disciplined self-improvement reflected Lincoln's belief that knowledge offered a path beyond the limitations of his birth. Lincoln's legal education followed this same pattern of determined self-study. Unable to afford formal law school, he borrowed law books from established attorneys and taught himself legal principles through intensive reading and observation in courtrooms. After gaining admission to the Illinois bar in 1836, Lincoln developed a successful practice that exposed him to diverse cases and clients across central Illinois. The law became not merely his profession but a framework for understanding justice and human relations. As he rode the circuit from county to county, Lincoln honed his ability to translate complex legal concepts into language ordinary citizens could understand—a skill that would later distinguish his political rhetoric. The 1830s and 1840s marked Lincoln's moral awakening regarding slavery. Though he had grown up with an instinctive dislike of the institution, his thinking evolved into a more coherent ethical position through both personal experience and intellectual engagement. In the Illinois legislature, where he served four terms beginning in 1834, Lincoln took the politically risky step of publicly protesting slavery, declaring it "founded on both injustice and bad policy." This early statement, while moderate by abolitionist standards, revealed Lincoln's willingness to take moral stands that transcended political expediency. Lincoln's moral development was profoundly influenced by his reading of the Declaration of Independence, which he came to view as America's moral founding document. He repeatedly invoked its assertion that "all men are created equal" as an ideal toward which the nation should strive, even if imperfectly realized. In his debates with Stephen Douglas years later, Lincoln would insist that the Declaration's principles applied to Black Americans, arguing that in the right to enjoy the fruits of their own labor, they were his equal and "the equal of every living man." The religious dimensions of Lincoln's moral thinking evolved throughout his life. Though never formally joining a church, Lincoln developed a profound theological understanding of providence and human responsibility. His early exposure to Baptist teachings, combined with his reading of the Bible and later engagement with Enlightenment thinkers, produced a distinctive moral framework that emphasized both human agency and submission to higher purposes. This spiritual perspective would later enable Lincoln to interpret the Civil War as a divine judgment on the national sin of slavery while maintaining hope for redemption and reconciliation. By the time Lincoln emerged as a national political figure in the 1850s, he had developed a moral vision that combined principled opposition to slavery with pragmatic recognition of constitutional constraints. This balance—moral clarity without self-righteousness, principled conviction without impractical absolutism—distinguished Lincoln from both proslavery Democrats and radical abolitionists. It reflected his remarkable capacity to hold together seemingly contradictory truths: that slavery was morally wrong yet legally protected, that racial prejudice was real yet human equality was undeniable, that political progress required both idealism and compromise.

Chapter 3: Political Rise and the Slavery Question

Lincoln's political career began conventionally enough with his election to the Illinois state legislature in 1834. As a Whig, he focused primarily on economic development issues like internal improvements and banking reform. While he personally disliked slavery, his public positions remained moderate. In an 1837 legislative resolution, he stated that slavery was "founded on both injustice and bad policy," but also acknowledged that Congress had no power to interfere with it in states where it existed. This balanced approach—moral clarity coupled with constitutional restraint—would characterize Lincoln's approach to slavery throughout his political rise. The 1850s marked Lincoln's transformation from a local politician to a national figure with a distinctive moral voice on slavery. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and opened northern territories to slavery under the principle of "popular sovereignty," galvanized Lincoln's opposition. In his famous Peoria speech of October 1854, he articulated a moral case against slavery's expansion: "If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that 'all men are created equal,' and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man's making a slave of another." This speech revealed Lincoln's ability to frame the slavery debate in terms of fundamental principles while acknowledging political realities. Lincoln's debates with Stephen Douglas during the 1858 Illinois Senate campaign further clarified his position on slavery and elevated him to national prominence. While Douglas advocated popular sovereignty—allowing settlers in each territory to decide the slavery question for themselves—Lincoln insisted that slavery must be recognized as a moral wrong and placed "in the course of ultimate extinction." In his famous "House Divided" speech opening the campaign, Lincoln warned that the nation could not endure permanently half slave and half free. Though he lost the Senate race, these debates established Lincoln as an eloquent antislavery voice who could appeal to moderate voters without embracing abolitionist extremism. What distinguished Lincoln's approach to the slavery question was his ability to balance moral conviction with political pragmatism. Unlike radical abolitionists who condemned the Constitution as a pro-slavery document, Lincoln worked within the constitutional framework while seeking to redirect the nation toward its founding ideals of liberty and equality. He acknowledged the legal protections slavery enjoyed in the states where it existed while insisting that the federal government had both the right and duty to prevent its expansion into new territories. This position—morally clear yet politically viable—allowed Lincoln to build the coalition necessary to win the presidency in 1860. Lincoln's election triggered the secession crisis, as Southern states viewed his victory as a threat to slavery despite his repeated assurances that he would not interfere with the institution where it existed. Throughout the secession winter of 1860-61, Lincoln steadfastly refused to compromise on the core Republican principle opposing slavery's expansion. This principled stand, which he believed essential to placing slavery "in the course of ultimate extinction," reflected Lincoln's conviction that some moral questions transcended political expediency. As he told one supporter, "I am not in a compromising mood... On the territorial question—that is, the question of extending slavery under national auspices—I am inflexible." By the time Lincoln took the presidential oath in March 1861, he had developed a coherent moral and political approach to slavery: opposition to its expansion, respect for constitutional limitations, and a long-term vision of emancipation. This position—evolving from his early self-education through his political maturation—would be tested and transformed by the unprecedented challenges of civil war. The frontier lawyer who had educated himself through borrowed books would soon face decisions affecting the lives of millions and the very survival of American democracy.

Chapter 4: Presidential Leadership in National Crisis

When Abraham Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861, seven Southern states had already seceded from the Union. His First Inaugural Address attempted to reassure Southerners that he had "no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists," while firmly declaring that secession was legally impossible. This delicate balance between conciliation and firmness characterized Lincoln's early approach to the crisis. The Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April forced his hand, leading to his call for 75,000 volunteers and the beginning of the Civil War. The early years of the war tested Lincoln's leadership in unprecedented ways. Military setbacks, political opposition, and foreign policy challenges required constant attention. Lincoln's management style combined respectful delegation with decisive intervention when necessary. He cycled through generals until finding in Ulysses S. Grant a commander who shared his strategic vision of relentless pressure on Confederate forces. With Secretary of State William Seward, he skillfully navigated international relations, preventing European recognition of the Confederacy despite initial British and French sympathy for the Southern cause. Lincoln's constitutional interpretation expanded to meet wartime necessities. He suspended habeas corpus along rail lines to Maryland, imposed a naval blockade, and authorized military trials in areas of rebellion—all without initial congressional approval. While critics accused him of dictatorial ambitions, Lincoln insisted these measures were necessary to preserve the Constitution itself. "Was it possible to lose the nation and yet preserve the Constitution?" he later asked rhetorically. His answer: "By general law, life and limb must be protected, yet often a limb must be amputated to save a life; but a life is never wisely given to save a limb." Throughout the conflict, Lincoln maintained a remarkable capacity to grow and learn. Initially defining the war's purpose solely as preservation of the Union, he gradually embraced emancipation as both a moral imperative and a military necessity. The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, though limited in scope to areas under Confederate control, fundamentally transformed the war's meaning. Lincoln later described it as "the central act of my administration, and the great event of the nineteenth century." His support for the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery throughout the nation, completed this evolution from preserving the Union with slavery intact to creating "a new birth of freedom." Lincoln's greatest leadership strength may have been his ability to communicate the war's purpose and meaning to the American people. The Gettysburg Address of November 1863 reinterpreted the conflict as a test of whether a nation "conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal" could endure. In just 272 words, Lincoln transformed understanding of both the war and American democracy itself. His Second Inaugural Address of March 1865 offered a profound theological reflection on the war as divine judgment for the national sin of slavery, concluding with a call for reconciliation "with malice toward none, with charity for all." Throughout the war's darkest moments, Lincoln maintained his essential humanity. He regularly visited hospitals to comfort wounded soldiers and showed compassion even toward deserters, often commuting death sentences. His famous sense of humor provided emotional release amid overwhelming pressures. When critics complained that General Grant drank too much, Lincoln reportedly replied, "Find out what brand of whiskey Grant drinks, because I want to send a barrel of it to each of my other generals." This combination of determination and humanity, principle and pragmatism, moral clarity and personal humility made Lincoln's presidential leadership during America's greatest crisis a model that continues to inspire.

Chapter 5: The Emancipation Journey

Abraham Lincoln's path to emancipation reflected both his moral convictions and his pragmatic understanding of political realities. When the Civil War began, Lincoln emphasized preserving the Union rather than ending slavery, telling newspaper editor Horace Greeley in August 1862: "If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it." This statement, often misinterpreted as indifference to slavery, actually reflected Lincoln's political strategy of keeping border slave states in the Union while preparing Northern public opinion for emancipation. By mid-1862, Lincoln had concluded that emancipation had become a military necessity. The war's escalating scale convinced him that the Union needed to strike at slavery, the Confederacy's economic foundation. On July 22, he presented his cabinet with a draft Emancipation Proclamation, explaining that he had "resolved upon this step, and had not called them together to ask their advice, but to lay the subject-matter of a proclamation before them." When Secretary of State Seward suggested waiting for a Union military victory to announce the policy, Lincoln agreed. Following the Battle of Antietam in September, Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, giving the Confederate states 100 days to return to the Union or face the freeing of their slaves. The final Emancipation Proclamation, issued January 1, 1863, was carefully crafted as a military measure based on the president's war powers. It applied only to states in rebellion, exempting border slave states and areas under Union control. Critics noted these limitations, with some abolitionists disappointed by its narrow scope and conservatives outraged by its radical implications. Yet despite its legal limitations, the proclamation fundamentally transformed the war's purpose and meaning. What began as a conflict to restore the Union became a revolution to create a new birth of freedom. As Frederick Douglass observed, the proclamation changed the Civil War "from a war for the Union into a war for liberty." The proclamation had profound military and diplomatic consequences. It authorized the enlistment of Black soldiers in the Union Army, eventually resulting in approximately 180,000 African American troops whose service proved crucial to Union victory. Lincoln recognized their importance, writing that "without the military help of the black freedmen, the war against the South could not have been won." Internationally, the proclamation effectively prevented European intervention on behalf of the Confederacy by transforming the conflict into a war against slavery, making it politically impossible for Britain or France to support the South. Lincoln's emancipation journey continued with his support for the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery throughout the nation. Though initially cautious about a constitutional amendment, by 1864 Lincoln had fully embraced it, making it part of the Republican platform and lobbying aggressively for its passage in Congress. When the House of Representatives finally approved the amendment in January 1865, Lincoln called it "a King's cure for all the evils" and "a great moral victory." This evolution—from opposing slavery's expansion to ending the institution entirely—reflected Lincoln's growth as both a moral leader and a practical politician. By the end of his life, Lincoln had begun contemplating what freedom would mean for formerly enslaved people in the postwar nation. Though still holding some conventional racial prejudices of his era, Lincoln had moved significantly toward supporting basic civil rights for African Americans. In his last public address on April 11, 1865, he publicly endorsed limited voting rights for Black men, particularly "the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks." This statement, which likely contributed to his assassination three days later, represented a remarkable evolution from his earlier views and suggested the direction his Reconstruction policies might have taken had he lived.

Chapter 6: Spiritual Evolution and Providence

Abraham Lincoln's religious views defy simple categorization. Raised in a Baptist household influenced by frontier revivalism, the young Lincoln developed a skeptical streak that earned him a reputation as a "freethinker" in his New Salem years. He never joined a church, rarely used conventional religious language, and maintained a certain intellectual distance from the denominational dogmas of his day. Yet throughout the Civil War, Lincoln increasingly framed the conflict and his own leadership in spiritual terms, developing what might be called a wartime faith centered on divine providence and moral purpose. The death of Lincoln's eleven-year-old son Willie in February 1862 marked a turning point in his spiritual journey. This devastating loss, coming amid the war's escalating casualties, drove Lincoln to seek meaning in suffering. White House staff noticed him reading the Bible more frequently after Willie's death, and he engaged in serious conversations about faith with his friend Joshua Speed and with Phineas Gurley, pastor of New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, which Lincoln regularly attended though never joined. While Lincoln never embraced orthodox Christianity in the manner many of his contemporaries wished, he developed a profound sense of divine purpose working through history and through his own leadership. Lincoln's evolving spirituality found its most eloquent expression in his Second Inaugural Address of March 4, 1865. In this remarkable speech, Lincoln interpreted the Civil War through a theological lens, suggesting that God had perhaps sent the war as punishment for the national sin of slavery: "If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him?" This providential understanding of history allowed Lincoln to call for reconciliation without triumphalism, concluding with his famous appeal for "malice toward none, with charity for all." Throughout the war, Lincoln resisted simplistic religious interpretations that claimed divine sanction for either side. When a delegation of ministers informed him that God was on the Union side, Lincoln reportedly replied, "I am not at all concerned about that, for I know that the Lord is always on the side of the right. But it is my constant anxiety and prayer that I and this nation should be on the Lord's side." This theological humility distinguished Lincoln from many religious leaders of his time who confidently proclaimed God's will in political matters. Lincoln's wartime writings and speeches reveal a leader wrestling with questions of divine purpose, human responsibility, and the meaning of suffering. In a private meditation written in September 1862 but never published in his lifetime, Lincoln reflected: "In the present civil war it is quite possible that God's purpose is something different from the purpose of either party." This willingness to acknowledge the limits of human understanding while maintaining faith in ultimate meaning characterized Lincoln's mature spiritual outlook. By the war's end, Lincoln had developed what historian Allen Guelzo calls a "theology of necessity" – a belief that human actions unfold within a providential framework that humans can only dimly perceive. This perspective allowed Lincoln to maintain both a sense of personal responsibility and a trust in larger purpose beyond human control. It enabled him to act decisively while remaining humble about his own understanding, to pursue victory while preparing for reconciliation. This spiritual maturity informed his leadership during the nation's greatest crisis and continues to inspire reflection on the relationship between faith and public service in American life.

Chapter 7: Legacy of Reconciliation and Equality

Abraham Lincoln's assassination on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, just five days after Lee's surrender at Appomattox, transformed him from a controversial wartime president into a martyred savior of the nation. His death at the moment of victory deprived America of his leadership during Reconstruction, raising one of history's great "what if" questions. Would his vision of "malice toward none, with charity for all" have produced a more just and reconciled post-war America? While this question remains unanswerable, Lincoln's legacy of reconciliation and equality has continued to shape American identity and inspire freedom movements worldwide. Lincoln's approach to reconstruction had begun taking shape before his death. His "Ten Percent Plan," announced in December 1863, offered relatively lenient terms for southern states to rejoin the Union. This moderate approach reflected Lincoln's primary goal of national healing rather than punishment. In his last cabinet meeting on April 14, 1865, Lincoln reportedly said, "I hope there will be no persecution, no bloody work after the war is over... Nobody need expect me to take any part in hanging or killing these men... Enough lives have been sacrificed." This emphasis on reconciliation rather than retribution established an important counterbalance to calls for vengeance that emerged after his assassination. The Thirteenth Amendment, which Lincoln had championed and which was ratified in December 1865, represented his most concrete legacy for equality. By constitutionally abolishing slavery throughout the United States, it fulfilled the promise of the Emancipation Proclamation and ensured that freedom would outlast the war. Yet Lincoln understood that legal freedom alone was insufficient. His support for the Freedmen's Bureau and his final public endorsement of limited voting rights for Black Americans suggested the direction his policies might have taken had he lived—a path of gradual but meaningful progress toward greater equality. Lincoln's legacy has evolved significantly over time, reflecting changing American attitudes about race and equality. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as America retreated from the promises of Reconstruction, Lincoln was often portrayed primarily as the savior of the Union rather than the Great Emancipator. The civil rights movement of the mid-20th century reclaimed Lincoln's emancipation legacy, with Martin Luther King Jr. deliberately choosing the Lincoln Memorial as the site for his "I Have a Dream" speech in 1963. King recognized that Lincoln's journey from conventional racial attitudes to becoming the Great Emancipator offered a powerful symbol of America's potential for moral growth. Beyond American shores, Lincoln's example has inspired freedom movements worldwide. His journey from poverty to the presidency exemplified democratic opportunity. His preservation of democratic government during civil war demonstrated that free societies could survive existential challenges. His commitment to human liberty, though imperfect by modern standards, provided a model for expanding the circle of freedom. Leaders from Mahatma Gandhi to Nelson Mandela have drawn inspiration from Lincoln's combination of principled conviction and pragmatic action, his ability to pursue justice while seeking reconciliation. Perhaps Lincoln's most enduring legacy is his demonstration that moral growth is possible both for individuals and nations. The Lincoln who entered the presidency in 1861 was not the same man who delivered the Second Inaugural in 1865. He had grown in moral understanding and spiritual depth through the crucible of war and personal tragedy. This capacity for growth—to learn from experience, to reconsider deeply held views, to expand one's moral imagination—offers hope that we too can transcend the limitations of our time and background. Lincoln reminds us that democracy is never finally secured but must be constantly defended and renewed by each generation, guided by what he called "the better angels of our nature."

Summary

Abraham Lincoln's enduring significance lies in his embodiment of America's highest ideals while acknowledging its deepest flaws. He preserved the Union through its greatest crisis while simultaneously transforming it, ensuring that "a new birth of freedom" would emerge from the crucible of civil war. His journey from frontier poverty to presidential greatness demonstrated the possibilities of self-improvement and democratic opportunity. Yet his leadership also revealed the necessity of moral courage in confronting entrenched injustice, even when that confrontation demands tremendous sacrifice. Lincoln's legacy offers essential wisdom for navigating our own divided times. His ability to combine principled conviction with pragmatic action, to grow beyond the prejudices of his era, and to articulate a vision of national purpose that transcended partisan division provides a model of democratic leadership at its best. His insistence that America must live up to the promise of its founding documents—that the Declaration's assertion of human equality must be made real in the lives of all Americans—remains an unfinished project. As he understood, democracy is never finally secured but must be constantly defended and renewed by each generation, guided by what he called "the better angels of our nature."

Best Quote

“In life, Lincoln’s motives were moral as well as political—a reminder that our finest presidents are those committed to bringing a flawed nation closer to the light, a mission that requires an understanding that politics divorced from conscience is fatal to the American experiment in liberty under law. In years of peril he pointed the country toward a future that was superior to the past and to the present; in years of strife he held steady. Lincoln’s life shows us that progress can be made by fallible and fallen presidents and peoples—which, in a fallible and fallen world, should give us hope.” ― Jon Meacham, And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights the book's ability to provide comfort and reassurance to admirers of Lincoln, describing it as a "warm, cozy blanket." It also appreciates the book's purpose as a corrective to contemporary critiques of Lincoln, aiming to restore his status and encourage understanding over cancellation.\nOverall Sentiment: Enthusiastic\nKey Takeaway: The book serves as both a comforting narrative for Lincoln admirers and a necessary corrective to modern critiques, emphasizing Lincoln's moral achievements and the importance of understanding his historical context rather than dismissing him.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.