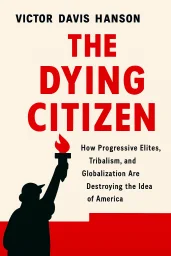

The Dying Citizen

How Progressive Elites, Tribalism, and Globalization Are Destroying the Idea of America

Categories

Nonfiction, Self Help, Psychology, Philosophy, Science, History, Economics, Politics, Audiobook, Sociology, Social Science, Society, Cultural, Political Science, Social, American History

Content Type

Book

Binding

Audiobook

Year

2021

Publisher

Basic Books

Language

English

ASIN

1549184474

ISBN

1549184474

ISBN13

9781549184475

File Download

PDF | EPUB

The Dying Citizen Plot Summary

Introduction

When Alexis de Tocqueville visited America in the 1830s, he marveled at a nation where citizens actively participated in their own governance. From town hall meetings to voluntary associations, Americans embodied a vibrant citizenship that balanced rights with responsibilities. This robust civic culture wasn't accidental—it rested on economic independence, shared cultural values, and institutions designed to channel self-interest toward the common good. Today, this foundation of American citizenship faces unprecedented challenges from multiple directions. The erosion of citizenship represents perhaps the greatest threat to America's constitutional order since the Civil War. As middle-class economic security has declined, tribal identities have resurged, and power has shifted from elected representatives to unelected bureaucrats. Meanwhile, globalization has created a class of "citizens of nowhere" with limited attachment to national communities. This book examines how these forces are transforming the very meaning of American citizenship and offers a path toward renewal. Whether you're concerned about political polarization, economic inequality, or cultural fragmentation, understanding the historical foundations of citizenship is essential for addressing today's constitutional crisis.

Chapter 1: Classical Foundations: Citizenship in Ancient Greece and Rome

The concept of citizenship was born in the ancient city-states of Greece around the 6th century BCE. In Athens, citizenship meant direct participation in governance through the ekklesia (assembly), where citizens voted on laws, declared war, and decided matters of state. This revolutionary system emerged when reformers like Solon and Cleisthenes expanded political participation beyond the aristocracy to include the middle class of small farmers and artisans. For the first time in human history, ordinary people gained political rights and responsibilities. However, citizenship in ancient Greece was highly exclusive. Women, slaves (who comprised nearly a third of the population), and resident foreigners (metics) were denied citizenship rights. Even among free males, citizenship required property ownership, military service, and proper lineage. The Athenians believed that economic independence was essential for political independence—a citizen needed to be free from economic coercion to vote his conscience. This explains why the Greeks viewed small farmers as the backbone of their democracies. The Romans expanded on Greek ideas of citizenship but transformed them for their growing empire. Unlike the direct democracy of Athens, Roman citizenship centered on legal rights rather than direct political participation. The proud declaration "civis Romanus sum" ("I am a Roman citizen") protected one from arbitrary punishment and guaranteed access to Roman courts. As Rome expanded, it gradually extended citizenship to conquered peoples, using it as a tool for integration rather than exclusion. By 212 CE, Emperor Caracalla granted citizenship to nearly all free inhabitants of the empire. The ancient world established fundamental principles of citizenship that would influence all future democracies. First, citizenship required active participation in civic affairs, not merely passive enjoyment of rights. Second, citizenship created equality before the law among those who possessed it. Third, citizenship was tied to military service—those who defended the state had a right to govern it. Finally, citizenship required economic independence, as those dependent on others could not exercise true political freedom. The decline of citizenship in ancient times offers sobering lessons. Both Athens and Rome eventually saw their citizen classes hollowed out by economic inequality, with small farmers displaced by large estates worked by slaves. As fewer citizens owned productive property, citizenship became increasingly meaningless, setting the stage for the rise of demagogues and eventually emperors who promised material benefits in exchange for political rights. This ancient pattern of citizenship's rise and fall would repeat throughout history, including in modern America.

Chapter 2: The American Republic: Creating a Nation of Citizens (1776-1950)

The American founding represented a revolutionary experiment in citizenship. Unlike European nations defined by blood and soil, America was founded on adherence to constitutional principles. The Founders, deeply influenced by classical republicanism, designed a system where citizenship would be based not on heredity but on commitment to certain ideals. This novel approach was captured in Thomas Jefferson's declaration that "all men are created equal" and endowed with "unalienable rights"—a radical departure from the hierarchical societies of the Old World. The Constitution established a framework for citizenship that balanced popular sovereignty with institutional constraints. The Bill of Rights protected individual liberties from government encroachment, while the separation of powers prevented any single faction from dominating. Citizenship in early America meant not just voting rights but responsibilities: jury service, militia duty, and civic participation. As George Washington noted in his Farewell Address, the Constitution could function only when supported by citizens with "enlightened confidence" in their government. Throughout the 19th century, American citizenship expanded through struggle and conflict. The Civil War and subsequent constitutional amendments abolished slavery and granted citizenship to former slaves. Women gained suffrage through the 19th Amendment in 1920 after decades of activism. The Homestead Act of 1862 distributed public lands to small farmers, furthering Jefferson's vision of an agrarian republic where economic independence would support political freedom. Each expansion of citizenship required reinterpreting founding principles to include previously excluded groups. The Great Depression and World War II transformed American citizenship by expanding its economic dimension. The New Deal created social insurance programs that provided economic security for millions, while the GI Bill after World War II enabled veterans to attend college and purchase homes. By 1950, over 60% of Americans could be classified as middle class, with stable employment, home ownership, and economic security. This broad middle class formed the foundation of American citizenship, as economically independent families had the time and resources for civic engagement. This period also saw the development of powerful assimilation mechanisms for immigrants. Public schools taught not just academic subjects but American civic values and history. Immigrants were expected to learn English and embrace constitutional principles while gradually shedding previous national loyalties. This "melting pot" approach created a distinctive American identity that transcended ethnic and religious differences. While imperfectly implemented, this model successfully integrated millions of newcomers from diverse backgrounds into a unified national community. The mid-20th century represented the high-water mark of American citizenship. Voter participation was high, and Americans joined civic organizations in record numbers. The shared experience of economic depression and world war had created a strong sense of national purpose that transcended class, regional, and ethnic divisions. This civic solidarity would be tested in subsequent decades as new challenges emerged to the economic, cultural, and institutional foundations of American citizenship.

Chapter 3: Economic Bifurcation: The Hollowing of Middle-Class Citizenship (1970-2020)

The 1970s marked a turning point for American citizenship as the postwar economic consensus began unraveling. The oil shocks, stagflation, and the collapse of the Bretton Woods monetary system signaled the end of the unprecedented prosperity that had supported middle-class citizenship. Manufacturing jobs, once the ladder to middle-class prosperity for millions without college degrees, began disappearing as companies moved production overseas. Between 1979 and 2010, the United States lost over 7 million manufacturing jobs, devastating communities that had relied on industrial employment for generations. This economic transformation created what the author calls a "bifurcated society" reminiscent of medieval structure: a small, wealthy elite at the top and a growing number of struggling citizens below. The statistics tell a troubling story: since 1979, the income share of the top 1% has more than doubled, while middle-class wages remained largely stagnant until recently. By 2020, approximately 58% of Americans had less than $1,000 in savings, while the average household carried over $8,000 in credit card debt at interest rates between 15-19%. This economic insecurity has profound implications for citizenship, as the ancient Greeks understood that economic independence is essential for political independence. Housing costs illustrate this bifurcation dramatically. In the early twentieth century, nearly half of Americans owned their homes. This percentage grew to 60% in the 1950s and peaked at almost 70% in 2004. By 2016, however, home ownership had fallen back to 63%—the lowest in nearly fifty years. For many Americans, particularly younger generations, home ownership has become an unattainable dream, especially in coastal urban areas where housing costs have far outpaced wage growth. Without property ownership, citizens lack the economic stake in society that the Founders considered essential for responsible citizenship. Higher education, once a reliable path to middle-class security, has become another economic trap. Between 1987 and 2017, tuition at public four-year institutions increased by 213% in inflation-adjusted dollars. Private colleges saw similar increases of 129%. These rising costs have coincided with administrative bloat, reduced teaching loads, and expanded non-academic services—all while graduate earnings have stagnated for many fields of study. The result is a generation burdened by $1.6 trillion in student loan debt, delaying family formation and home ownership. The consequences extend beyond economics into family formation and social stability. The average age of first marriage has risen dramatically—from about 23 for men and 22 for women in 1950 to 30 and 29 respectively by 2019. Similarly, the average age for first childbirth among women has increased from 21 in the early 1970s to nearly 27 today. Family size has shrunk from an average of 2.3 children in the 1960s to 1.9 today—below the 2.1 replacement rate needed to maintain population levels. Without economic security, many Americans are delaying or forgoing traditional markers of adult citizenship altogether. This economic bifurcation has created a new class of dependent citizens who rely on government assistance for basic needs. Approximately 20% of Americans receive direct government assistance, and over half depend on some form of government transfer payment. This growing dependence fundamentally alters the citizen-state relationship, transforming citizens from independent actors in a constitutional republic to clients of an administrative state. As economic independence erodes, so too does the foundation of citizenship that has sustained American democracy since its founding.

Chapter 4: Identity Politics: The Return of Tribal Divisions

The resurgence of tribal identity represents one of the most significant challenges to American citizenship in recent decades. From the nation's founding through the civil rights movement, the trajectory of American history had been toward a more universal citizenship that transcended particular identities. Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream of judging people by "the content of their character rather than the color of their skin" represented the culmination of this universalist vision. Since the 1970s, however, this trajectory has reversed as group identity based on race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation has increasingly competed with national identity. This tribal turn has transformed institutions across American society. Universities now routinely conduct separate graduation ceremonies based on race and ethnicity. Government agencies and the census track Americans' complicated ethnic lineages to adjudicate claims for preferential treatment in hiring and admissions. Even the vocabulary of American life has changed, with hyphenated identities becoming increasingly common as markers of ethnic pride and potential career advantage. The result is what political scientist Samuel Huntington called the "deconstructing of America"—the fragmentation of national identity into competing tribal claims. The ancient Greeks recognized tribalism as pre-civilizational. Thucydides described tribal peoples as "hopelessly nomadic" and unable to establish stable societies because they lacked the unifying force of law. The invention of politics and constitutional government initiated humanity's slow ascent over tribalism, as diverse ethnicities surrendered their primary identities to transcendent ideas and traditions. America's unique achievement was extending this concept across unprecedented racial and ethnic diversity. Unlike most nations throughout history, which defined citizenship through blood and soil, America defined it through adherence to constitutional principles. This achievement is now under threat as identity politics encourages Americans to define themselves primarily through immutable characteristics rather than shared citizenship. The paradox is that as society becomes more racially mixed, the fixation on racial identity only intensifies. As Richard Alba noted in "The Great Demographic Illusion," more than 10% of all babies born in the United States now come from mixed majority-minority families with one white parent and one nonwhite or Hispanic parent. Yet our tribal politics struggles to accommodate this complex reality, instead forcing citizens into increasingly rigid identity categories. The consequences of this tribal turn extend beyond domestic politics to national security. Foreign adversaries have skillfully exploited American racial tensions in their propaganda, knowing that a nation divided against itself cannot effectively counter external threats. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese state media deflected legitimate criticism by charging racism, confident that many Americans would echo these accusations rather than defend national interests. Evidence suggests some foreign powers have directly funded identity politics groups within the United States, recognizing that tribal division weakens their greatest geopolitical rival. Perhaps most fundamentally, tribalism destroys the individualism that has been central to American citizenship. When people are defined primarily by group identity rather than individual character and achievement, society becomes a zero-sum competition between collectives rather than a community of equal citizens. As columnist Christopher Hitchens observed, "People who think with their epidermis or their genitalia or their clan are the problem to begin with. One does not banish this specter by invoking it." The challenge for American citizenship is to reclaim the universalist vision that once united the nation across its remarkable diversity.

Chapter 5: The Administrative State: Unelected Power vs. Democratic Accountability

The rise of the administrative state represents a profound challenge to constitutional citizenship—a "state within a state" that increasingly operates beyond the control of elected officials and ordinary citizens. This vast archipelago of federal agencies, staffed by approximately 2.7 million bureaucrats, has accumulated unprecedented power to make, enforce, and adjudicate rules that affect every aspect of American life. The Federal Register, which contains federal regulations, now spans 175,496 pages across 235 volumes—a dramatic expansion from its modest beginnings. This transformation began during the Progressive Era when intellectuals like Woodrow Wilson explicitly rejected the Founders' skepticism about human nature and government power. Wilson argued that the Constitution's checks and balances were outdated constraints designed for a simpler era. He envisioned a more "scientific" approach to governance led by expert administrators rather than elected representatives constrained by constitutional limitations. This administrative state would be guided not by the people's representatives but by educated elites with specialized knowledge deemed beyond the comprehension of ordinary citizens. The New Deal dramatically expanded this administrative approach, creating dozens of new agencies with broad regulatory powers. The Supreme Court initially resisted this expansion, striking down key New Deal programs as unconstitutional delegations of legislative power to the executive branch. By 1937, however, the Court reversed course, allowing Congress to delegate vast authority to administrative agencies. This "constitutional revolution" fundamentally altered the separation of powers, creating what Justice Robert Jackson later called a "fourth branch" of government not clearly authorized by the Constitution. The danger intensified in recent decades as the administrative state became increasingly insulated from democratic accountability. In 2016 alone, federal departments issued 3,853 new rules compared to just 214 laws passed by Congress and signed by the president—a ratio of 18 to 1. This represents a massive transfer of legislative power from elected representatives to unelected bureaucrats. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court's "Chevron doctrine" instructs judges to defer to agencies' interpretations of ambiguous statutes, further insulating bureaucratic decisions from judicial review. The administrative state combines legislative, judicial, and executive powers in a single entity—precisely the dangerous concentration of authority the Constitution was designed to prevent. A regulator can create a rule, judge whether a citizen has broken it, and then enforce punishment, all without direct accountability to voters. Examples abound: The Environmental Protection Agency's 2015 Clean Water Rule extended federal jurisdiction from "navigable waters" to even temporary puddles on private property. The Raisin Administrative Committee, a Depression-era agency, claimed ownership of farmers' raisin crops and confiscated up to 75% of annual harvests without compensation. This concentration of power in unelected hands represents perhaps the most direct threat to citizenship in a constitutional republic. When citizens can no longer control their government through elections, when laws are made by officials they cannot remove from office, the very foundation of democratic governance is undermined. As sociologist Robert Nisbet observed, "When bureaucracy reaches a certain degree of mass and power, it becomes almost automatically resistant to any will, including the elected will of the people, that is not of its own making." Restoring democratic accountability requires reining in administrative power and returning lawmaking authority to elected representatives.

Chapter 6: Globalism vs. Nationalism: The Citizen of Nowhere

The tension between global and national identities represents perhaps the most subtle yet pervasive challenge to American citizenship in the modern era. Since World War II, and particularly after the Cold War ended in 1991, globalization has transformed economics, culture, and politics. Trade barriers fell, capital flowed freely across borders, and new technologies enabled instant communication worldwide. This interconnected world created unprecedented opportunities but also fundamentally challenged traditional conceptions of citizenship tied to national communities. The globalist perspective, embraced by many economic, cultural, and political elites, envisions citizens not primarily as members of particular nations but as "citizens of the world" with universal rights and responsibilities that transcend national boundaries. This cosmopolitan ideal has ancient roots in Socratic utopianism but has gained unprecedented momentum through twenty-first-century global integration. Corporate leaders, academics, media figures, and political elites increasingly share a transnational perspective that prioritizes global concerns over national interests. This worldview manifests concretely in annual gatherings like the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, where approximately three thousand global elites assemble to discuss international issues. As political scientist Samuel Huntington noted, these "Davos Men" are "more likely to spend their time chatting with their peers around the world than talking with their neighbors around the corner." Their loyalties transcend national boundaries, oriented instead toward a transnational class of like-minded elites with similar educational backgrounds, consumption patterns, and cultural values. The globalist vision offers compelling benefits: expanded human rights, environmental protection beyond national boundaries, free movement of people and goods, and peaceful cooperation among formerly hostile nations. Yet it also poses fundamental challenges to constitutional citizenship, which depends on defined borders, shared culture, and democratic accountability within sovereign nations. When decisions increasingly shift from elected national governments to international organizations, multinational corporations, and transnational legal regimes, citizens lose their ability to influence policies through democratic processes. Perhaps most significantly, globalism creates a disconnect between elites who benefit from international integration and ordinary citizens who bear its costs. When manufacturing jobs move overseas, professional classes gain from cheaper goods while working classes lose stable employment. When immigration increases, cosmopolitan elites gain cultural diversity and affordable services while less-educated workers face wage competition. This economic bifurcation undermines the middle-class foundation of citizenship discussed earlier. The ultimate danger is not that globalism will westernize the world but that it will internationalize America—dissolving the distinctive constitutional culture that has made American citizenship exceptional. As British Prime Minister Theresa May critically observed, some elites consider themselves "citizens of nowhere," with limited allegiance to particular countries or traditions. This cosmopolitan identity contrasts sharply with the national patriotism that has traditionally motivated civic engagement and sacrifice for fellow citizens. Restoring a healthy balance between global engagement and national identity represents one of the central challenges for American citizenship in the twenty-first century.

Chapter 7: The Path Forward: Renewing American Citizenship

The renewal of American citizenship requires addressing the multiple challenges that have eroded its foundations. This path forward begins with economic revitalization of the middle class—the historical backbone of republican citizenship. Just as the GI Bill and homeownership programs created broad-based prosperity after World War II, new policies must aim to restore economic independence for ordinary citizens. This means rethinking education to emphasize practical skills alongside theoretical knowledge, reforming housing policies to make homeownership attainable for young families, and reconsidering trade and immigration policies to prioritize the interests of American workers. Civic education represents another crucial element in citizenship renewal. For generations, American schools taught not just academic subjects but the principles and practices of citizenship. Students learned constitutional history, civic responsibilities, and the habits of democratic participation. This educational foundation has eroded as schools increasingly focus on career preparation or identity politics rather than civic formation. Restoring robust civic education—not as partisan indoctrination but as preparation for democratic citizenship—would help create a shared understanding of American principles across diverse communities. The administrative state must be reformed to restore democratic accountability. This means reducing the scope of bureaucratic authority, requiring congressional approval for major regulations, and revisiting judicial doctrines that defer to agency interpretations. The goal is not to eliminate necessary expertise in governance but to ensure that unelected officials remain accountable to the people through their elected representatives. When citizens feel that their votes matter in determining government policies, they become more engaged in the democratic process rather than retreating into cynicism or apathy. Immigration policy requires balancing America's tradition of welcoming newcomers with the need for meaningful citizenship. This means creating clearer paths to citizenship for those who enter legally while enforcing borders and immigration laws. It also means revitalizing assimilation—not as forced conformity but as integration into a shared civic culture. Learning English, understanding constitutional principles, and developing attachment to American institutions should be expected of those seeking citizenship. These expectations honor rather than demean immigrants by inviting them into full participation in the American experiment. Perhaps most fundamentally, renewing citizenship requires transcending tribal divisions through a recommitment to universal principles. This means rejecting both white nationalism and progressive identity politics in favor of a citizenship that treats individuals as equals regardless of immutable characteristics. It means recognizing legitimate group concerns while insisting that our primary political identity must be as American citizens rather than as members of racial, ethnic, or gender categories. This universalist vision has deep roots in both classical republicanism and the civil rights movement. The challenges facing American citizenship are formidable but not insurmountable. Throughout its history, the nation has faced moments of crisis that threatened its constitutional foundations, from the Civil War to the Great Depression to the turbulent 1960s. Each time, Americans found ways to renew their commitment to the principles of liberty and self-governance that define their unique experiment in democratic republicanism. By addressing the economic, educational, administrative, immigration, and cultural challenges to citizenship, Americans can once again revitalize the foundations of their constitutional order for future generations.

Summary

The decline of American citizenship represents a convergence of multiple forces that together threaten the foundation of constitutional government. From economic bifurcation that has hollowed out the middle class, to tribal identities that fragment the body politic, to administrative power that evades democratic accountability, to globalist perspectives that weaken national bonds—each challenge strikes at a different aspect of citizenship. Yet these diverse threats share a common pattern visible throughout history: when citizenship declines, republics falter. The ancient world saw this pattern in Athens and Rome, where economic inequality and tribal division eventually undermined democratic institutions. America now faces a similar test. The path forward requires renewing citizenship's foundations while adapting to contemporary realities. Economic independence must be restored through policies that rebuild the middle class and create broadly shared prosperity. Civic education needs revival, teaching not just rights but responsibilities of citizenship. The administrative state must be reformed to restore democratic accountability, while immigration policy should welcome newcomers while maintaining meaningful citizenship. Perhaps most importantly, Americans must transcend tribal divisions through recommitment to universal principles that unite rather than divide. These steps won't resolve all disagreements—robust debate is essential to democracy—but they can restore the common ground of citizenship that makes peaceful resolution of differences possible. The American experiment has faced existential challenges before and survived through renewal of its founding principles. The current crisis demands nothing less.

Best Quote

“Saving the world is a much more ambitious, ennobling, and ego-gratifying project than preserving the neighborhood.” ― Victor Davis Hanson, The Dying Citizen: How Progressive Elites, Tribalism, and Globalization Are Destroying the Idea of America

Review Summary

Strengths: The review highlights the author's expertise and the historical context provided in the book. It also mentions the expansion of citizenship rights over time. Weaknesses: The review does not provide specific examples of modern-day threats to citizenship in America, leaving the reader curious about the book's analysis of this issue. Overall: The review presents the book as insightful and informative, particularly in its exploration of citizenship roots. Readers interested in history and citizenship rights may find this book valuable.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.