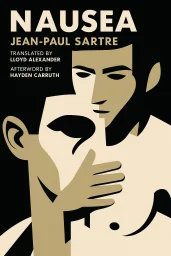

Nausea

Explore and Question the Very Essence of Existence

Categories

Philosophy, Fiction, Classics, Literature, 20th Century, France, Novels, French Literature, Literary Fiction, Nobel Prize

Content Type

Book

Binding

Hardcover

Year

1968

Publisher

New Directions

Language

English

ASIN

0811201880

ISBN

0811201880

ISBN13

9780811201889

File Download

PDF | EPUB

Nausea Plot Summary

Introduction

Existentialism emerges as a powerful response to the crisis of meaning in the modern world. At its core lies a radical proposition: human beings exist first, without predetermined purpose, and must create their own essence through choices and actions. This philosophical stance represents a dramatic break from traditional notions that humans possess an inherent nature or purpose defined by God, reason, or natural law. Through vivid, often unsettling narratives and meticulous phenomenological descriptions, we witness the protagonist's journey from the comfortable illusions of everyday existence to the raw, nauseating confrontation with the fundamental contingency of all things. The journey through existential awakening follows a distinct trajectory - from the initial shock of perceiving existence in its raw, meaningless state to the subsequent challenge of creating authentic meaning in a world without given purpose. What makes this intellectual venture so compelling is how it transforms abstract metaphysical concepts into lived experiences that resonate with universal human struggles. The nauseating recognition that no transcendent meaning exists becomes not an endpoint but a starting point for genuine freedom. By following this trajectory, we can better understand how confronting existential dread might paradoxically open possibilities for authentic living, examining how the protagonist's painful awakening reveals the structures of self-deception that most humans employ to avoid facing the fundamental absurdity of existence.

Chapter 1: The Revelation of Contingent Existence and Nausea

The existential journey begins with a profoundly disorienting experience - a sudden, overwhelming perception that everything exists without reason, necessity, or justification. This revelation manifests physically as a sensation of nausea, a visceral revolt against the gratuitous nature of being. The protagonist, Antoine Roquentin, experiences this first through ordinary objects that suddenly appear strange and threatening. A simple pebble on a beach, a seat in a tramway, or a glass of beer becomes unnervingly present, excessive, and absurd. These mundane objects lose their familiar meanings and utility, appearing instead as raw, purposeless existents. This nausea represents more than mere physical discomfort; it marks the collapse of the conceptual frameworks through which humans typically organize their experience. Language itself begins to fail as words detach from things. When Roquentin stares at the root of a chestnut tree in the park, he experiences a pivotal moment where concepts like "root" or "black" no longer adequately capture the overwhelming presence of the thing itself. The root exists with a bizarre, obscene fullness that defies categorization or explanation. It simply is, without reason or necessity - revealing the contingency at the heart of all existence. The physical symptoms of nausea correspond directly to metaphysical insights. When Roquentin feels dizzy, nauseated, and disoriented, these sensations reflect his mind's inability to process existence without the mediating structures of human categories and purposes. Existence appears as a formless, undifferentiated mass - slimy, viscous, and overwhelming. The world no longer appears as a collection of stable objects with clear identities and purposes but as a continuous, pulsating flow of being without divisions or meaning. What makes this revelation so disturbing is its universality - it applies not only to external objects but to human existence itself. Roquentin realizes that his own existence is equally contingent, unnecessary, and unjustified. There is no reason why he exists rather than not existing; he simply finds himself "thrown" into being. This insight strikes at the heart of human pretensions to necessity or importance. Humans prefer to think of themselves as necessary, as fulfilling some essential purpose in the universe, but the nausea reveals this as a comforting illusion. The intensity of this experience cannot be sustained indefinitely. Roquentin oscillates between moments of acute awareness and periods of relative normalcy when conventional meanings reassert themselves. Yet once glimpsed, the contingency of existence can never be entirely forgotten. This fluctuation itself becomes significant, suggesting that humans cannot permanently dwell in raw existential awareness but must construct meanings to make life bearable, even while recognizing these meanings as human creations rather than discoveries of inherent purpose. Ultimately, the nausea functions as both symptom and revelation - it is simultaneously the physical manifestation of existential insight and the vehicle through which that insight is delivered. Through this unpleasant bodily experience, Roquentin gains access to fundamental truths about existence that remain hidden from those who have not undergone similar experiences. The nausea thus serves as an unwelcome gift - a painful initiation into a more authentic relationship with being.

Chapter 2: Freedom and Responsibility in a World Without Meaning

The collapse of inherent meaning creates a dizzying freedom that is simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying. Once Roquentin recognizes that no predetermined essence or purpose governs human existence, he confronts the radical freedom that follows from this absence. Humans are not bound by divine plans, natural laws, or predetermined destinies - they exist first and must subsequently create their essence through choices and actions. This reversal of traditional metaphysics - where existence precedes essence rather than essence preceding existence - constitutes the foundational insight of existentialist thought. This freedom manifests most clearly in moments of decision where no external standard determines the correct choice. When Roquentin contemplates whether to remain in Bouville or leave for Paris, whether to continue his historical research or abandon it, he discovers that no objective criteria exist to guide these decisions. Traditional sources of authority - religion, social convention, rationality - prove inadequate because they ultimately rest on groundless human choices rather than transcendent truths. Every decision requires a leap beyond evidence or reason, a commitment made without guarantee. Yet this freedom comes paired with a weighty responsibility that many find unbearable. If humans create meaning through their choices rather than discovering pre-existing meaning, they bear complete responsibility for the world they help create. Roquentin observes how most people flee this responsibility through various forms of self-deception. The bourgeois citizens of Bouville construct elaborate justifications for their lives, pretending their conventional choices reflect necessary truths rather than contingent decisions. They create identities as "respectable citizens" or "self-made men" to mask the arbitrariness of their existence. The concept of "bad faith" emerges as a central diagnosis of this evasion of freedom and responsibility. Bad faith involves treating oneself as a fixed object with determined properties rather than as a free consciousness that transcends all determination. The Self-Taught Man exemplifies this bad faith through his mechanical alphabetical reading program and his humanistic platitudes, which shield him from confronting the groundlessness of his own existence. Similarly, the museum portraits of Bouville's "distinguished citizens" represent attempts to solidify contingent lives into necessary identities. Authentic existence, by contrast, requires embracing both freedom and the anxiety it produces. Roquentin experiences moments of authenticity when he acknowledges the groundlessness of his choices yet makes them anyway, without pretending they rest on anything beyond his own decision. These moments often occur during his wanderings through Bouville, when he temporarily suspends conventional frameworks and allows himself to experience the raw contingency of existence without fleeing into bad faith. Though frightening, these experiences contain a strange exhilaration - the vertigo of absolute freedom. The ultimate challenge becomes creating meaning in full awareness of its contingency. Any meaning humans create lacks the guarantee of transcendent truth, yet creating meaning remains necessary for human flourishing. This paradox leads Roquentin toward art as a potential solution - not as a discovery of inherent meaning but as a conscious creation of patterns that acknowledge their own contingency while providing orientation in an absurd world. His final consideration of writing a novel suggests not an escape from contingency but an authentic response to it.

Chapter 3: The Illusion of Perfect Moments and Social Roles

A critical dimension of existential awakening involves recognizing how humans construct illusory narratives and roles to evade confrontation with raw existence. Roquentin's recollections of Anny, his former lover, reveal her obsession with creating "perfect moments" - carefully choreographed experiences designed to achieve a transcendent significance beyond ordinary existence. These moments required precise behaviors, specific settings, and exact words to create the illusion of necessity and meaning. Anny's disappointment invariably followed when reality failed to conform to her expectations, when some element - a redheaded stranger, a misspoken word - disrupted the perfection she sought. These perfect moments exemplify how humans impose narrative structures on formless experience. Roquentin realizes that adventures, like perfect moments, exist only in retrospect, when events have been organized into stories with beginnings, middles, and ends. While living through experiences, no such narrative coherence exists - only a succession of present moments without inherent structure or significance. The narrative coherence emerges afterward, through selective remembering and organizing that falsifies the formlessness of lived experience. This insight leads to Roquentin's devastating conclusion: "You have to choose: live or tell." Social roles provide another mechanism for evading existential awareness. Throughout Bouville, Roquentin observes people who have thoroughly identified with their social functions - the café owner, the Sunday stroller, the respected businessman. By reducing themselves to these roles, they create the comforting illusion of solid identity and purpose. The portraits in the Bouville museum represent the apotheosis of this self-deception, displaying distinguished citizens who appear to embody necessity and permanence rather than contingency and temporality. Roquentin's visceral disgust toward these portraits stems from their fundamental dishonesty - their attempt to disguise arbitrary existence as essential being. The Self-Taught Man exemplifies this evasion through social role-playing. His mechanical alphabetical reading program and his empty humanist platitudes provide him with a ready-made identity that shields him from confronting his groundless freedom. When he pronounces clichés about the brotherhood of man, he speaks not as himself but as "The Humanist," a social type that offers predetermined responses to life's questions. The violent exposure of his sexual attraction to young boys reveals the fragility of this constructed identity, showing how easily social masks can be stripped away to reveal the contingent existence beneath. Even time itself becomes implicated in these evasions. Conventional understandings of time as a linear progression with past, present, and future provide another framework that disguises the formlessness of existence. Roquentin experiences moments when this temporal framework collapses, when the distinctions between past, present, and future dissolve into an overwhelming present without structure. These experiences prove particularly disorienting because they undermine one of the most fundamental organizing principles of human experience - the sense of time as an ordered sequence rather than an undifferentiated flow. The existential challenge becomes living without these illusory supports while avoiding despair. Roquentin gradually recognizes that authentic existence requires neither embracing chaos nor clinging to false certainties, but rather creating meanings while maintaining awareness of their contingency. This difficult balance - creating without self-deception, choosing without pretending the choice was necessary - points toward the possibility of authentic existence beyond both nihilism and bad faith.

Chapter 4: Authenticity Versus Self-Deception in Human Relationships

Existential awareness profoundly transforms human relationships, exposing how interpersonal connections often function as elaborate systems of mutual self-deception. Roquentin observes that most relationships in Bouville operate as tacit agreements to reinforce comforting illusions about existence. Couples, friends, and colleagues validate each other's roles and narratives, creating a shared reality that shields them from confronting the contingency of their existence. The Sunday strollers along the seaside promenade exemplify this mutual reinforcement, exchanging pleasant greetings that affirm their respectable identities while avoiding any genuine encounter with each other or with the groundlessness of their situation. Authentic relationships, by contrast, would require acknowledging both one's own freedom and the freedom of the other. Such relationships prove exceedingly rare because they offer no protection from existential anxiety. When Roquentin reconnects with Anny, their meeting reveals the difficulty of authentic connection. Their previous relationship had been structured around her concept of "perfect moments," with Roquentin playing an assigned role in her carefully choreographed scenes. Now that Anny has abandoned belief in perfect moments, recognizing them as illusory attempts to impose necessity on contingent existence, their relationship lacks its organizing principle. They confront each other as two free consciousnesses without predetermined roles or scripts. The failure of their reunion demonstrates how relationships typically depend on mutual bad faith. Without shared illusions to mediate their encounter, Roquentin and Anny find themselves unable to establish meaningful connection. Their conversation becomes painfully direct as they acknowledge the changes in each other without the cushioning effects of polite deception. Anny's admission that "I outlive myself" parallels Roquentin's own recognition that existence continues even after meaning has collapsed. Their parallel insights create a momentary authentic connection, but this proves insufficient to sustain a relationship once the organizing fantasies have dissolved. Sexual relationships particularly reveal the tensions between authenticity and self-deception. Roquentin's encounters with the patronne of the "Railwaymen's Rendezvous" involve no pretense of romantic love or transcendent connection - they represent a mutual satisfaction of physical needs without illusion. Yet even these encounters lack true authenticity because they involve treating each other as objects rather than as free consciousnesses. The Self-Taught Man's attraction to young boys similarly reduces others to objects of desire rather than recognizing their freedom, though his humanist platitudes attempt to disguise this objectification as universal brotherhood. The possibility of authentic love would require a seemingly impossible balance: recognizing the other's absolute freedom while creating contingent meanings together. Neither treating the other as a means to one's own ends nor expecting the other to provide necessary meaning for one's existence, authentic love would involve two free consciousnesses choosing each other without pretending this choice was fated or necessary. The absence of such relationships in Roquentin's experience suggests their rarity or perhaps impossibility in a world where most people flee from freedom into bad faith. This analysis extends beyond intimate relationships to all forms of human connection. Roquentin's interactions with the café patrons, the museum attendants, and the library visitors all reveal the same patterns of mutual reinforcement of comforting illusions. Even seemingly trivial social conventions - greetings, small talk, polite inquiries - function as systems for avoiding authentic encounter with others' freedom and with the contingency of existence. True human connection would require dismantling these protective conventions and risking genuine presence with others, with all the vulnerability this entails.

Chapter 5: Art and Writing as Potential Paths to Transcendence

The crisis of meaning precipitated by existential awakening ultimately points toward creative activity as a potential response to the absurdity of existence. Throughout his journey, Roquentin encounters various aesthetic experiences that momentarily transcend the nauseating contingency of raw existence. Most significantly, a jazz recording in the café - "Some of these days" - provides a fleeting sense of necessity and permanence amid the flux of contingent existence. Unlike physical objects that simply exist without reason or justification, the melody seems to stand outside time, possessing a kind of necessity that ordinary existents lack. It was created rather than merely existing, embodying human meaning-making rather than brute facticity. This aesthetic experience suggests a crucial distinction between existence and creation. While existence simply is, without reason or necessity, human creations can embody intentions and purposes. The melody exists physically as vibrations in air, as grooves on a record, but transcends this physical existence through its structure and emotional impact. Roquentin imagines the Jewish composer in New York creating the melody amid personal struggles and physical discomfort - transforming contingent suffering into necessary form. The melody does not escape contingency entirely, but transforms it into something that appears to transcend mere existence. Roquentin's epiphany about artistic creation points toward writing as his own potential salvation. If he cannot find meaning in existence itself, perhaps he can create meaning through artistic activity. Not historical writing that attempts to capture what actually existed - his abandoned biography of the Marquis de Rollebon represented this futile approach - but fiction that transforms contingency into apparent necessity through aesthetic form. A novel would not pretend to discover meaning in the world but would consciously create patterns that acknowledge their own contingency while providing orientation in an absurd universe. This potential resolution involves neither a return to naive belief in transcendent meaning nor surrender to nihilistic despair. Instead, it suggests a third path: the conscious creation of human meanings that acknowledge their own contingency while still providing genuine value. The jazz melody was created by a suffering human being in specific historical circumstances, yet it speaks across time and circumstance, creating a pocket of apparent necessity within contingent existence. Similarly, Roquentin's proposed novel would transform his nauseating experiences into aesthetic form, not denying their contingency but transmuting it through creative activity. Importantly, this aesthetic solution differs from mere escapism. The jazz melody does not simply distract Roquentin from existential nausea but engages with it directly, transforming formless suffering into formed expression. Likewise, his potential novel would not turn away from the absurdity of existence but would confront it through artistic creation. This represents not a denial of existential insights but their incorporation into a new relationship with existence - neither naive acceptance nor complete rejection, but creative transformation. The final pages suggest a tentative hope through this aesthetic resolution. Roquentin's decision to leave Bouville for Paris to begin writing signals not an escape from existential awareness but a commitment to engage with it through creative activity. His project remains uncertain - he questions his talent and capacity for sustained creative work - but represents a potential path beyond both the nauseating confrontation with raw existence and the self-deceptive evasions of bad faith. By creating rather than merely existing, he might establish an authentic relationship with his own contingency and freedom.

Chapter 6: The Existentialist Challenge to Traditional Humanism

The existential awakening fundamentally challenges traditional humanist assumptions about human nature, rationality, and progress. Throughout his journey, Roquentin encounters various forms of humanism that attempt to provide comforting frameworks of meaning in the absence of religious certainty. The Self-Taught Man exemplifies this secular humanism with his belief in human brotherhood, rational progress, and cultural improvement. His alphabetical reading program represents a touching but naive faith in knowledge as salvation, while his humanitarian platitudes express conventional optimism about human potential. Yet Roquentin perceives these humanist beliefs as sophisticated forms of self-deception - attempts to replace God with Man as the source of meaning without confronting the radical contingency of all human values. Traditional humanism assumes humans possess an essential nature that defines their potential and prescribes their proper development. It replaces divine purpose with natural human purposes, suggesting that authentic human flourishing involves realizing innate human capacities for reason, cooperation, and moral development. Against this essentialist view, existential awakening reveals that human existence precedes any defined essence - humans exist first and subsequently create their nature through choices and actions. No predetermined human nature exists to guide these choices or guarantee their value. This absence of inherent human essence undermines all humanistic attempts to derive normative guidelines from assumptions about "human nature." The portraits in the Bouville museum particularly exemplify this critique of traditional humanism. These distinguished citizens embody Enlightenment and bourgeois humanist values - rationality, dignity, self-development, civic contribution, and cultural refinement. Yet Roquentin perceives their self-important poses as elaborate disguises for the contingency and meaninglessness of their existence. Their apparent dignity and purpose mask the fundamental absurdity of all human endeavors. The museum visitors who reverently observe these portraits participate in this collective self-deception, affirming humanist values that lack any foundation beyond human choice. Political and social forms of humanism fare no better under existential scrutiny. The Self-Taught Man's socialism and the civic pride of Bouville's citizens represent attempts to create collective meaning through social progress and community development. Yet these projects ultimately rest on contingent values that cannot claim necessary truth or universal validity. Social progress implies movement toward predetermined human goods, but existential awareness reveals that these goods themselves are human creations rather than discoveries of natural or rational necessities. The historical narratives that support these progressive visions - evident in the newspaper articles Roquentin reads - impose artificial coherence on the formless flow of events. Even scientific humanism, with its faith in rational inquiry and empirical knowledge, encounters existential limitations. Rational categories and scientific laws represent human impositions on formless existence rather than discoveries of inherent structures in reality. When Roquentin experiences the nausea, conceptual distinctions between objects dissolve, revealing the artificial nature of scientific categorizations. The contingency of existence precedes and exceeds all rational frameworks, which function as useful but ultimately groundless human constructions rather than revelations of necessary truth. The existentialist challenge to humanism does not necessarily entail nihilism or anti-humanism. Rather, it suggests the possibility of a post-metaphysical humanism that creates values without pretending they reflect transcendent truths. This reconstructed humanism would acknowledge the contingency of all human values while still affirming their importance for human flourishing. It would create meanings without self-deception, choosing human goods while recognizing these goods as human creations rather than discoveries. This difficult balance - valuing without metaphysical guarantees, creating without self-deception - points toward an authentic humanism beyond both traditional certainties and nihilistic despair.

Summary

The existential journey illuminates a fundamental paradox of human existence: authentic living requires confronting the absence of inherent meaning while nevertheless creating meaning through choice and action. This synthesis emerges not as a comfortable middle path but as a challenging balancing act - acknowledging contingency without surrendering to nihilism, creating values without pretending they reflect transcendent truths. The nauseating recognition that existence precedes essence, that humans exist without predetermined purpose, becomes not an endpoint but a starting point for genuine freedom. By moving through the stages of existential awakening - from the disorienting collapse of conventional meanings through the temptations of nihilism and self-deception to the possibility of authentic creation - we witness how confronting existential dread might paradoxically open possibilities for more genuine engagement with life. What ultimately distinguishes this philosophical journey is its refusal of easy consolation. Neither returning to traditional certainties nor surrendering to meaninglessness, it charts a difficult path of clear-eyed creation. The jazz melody that provides momentary transcendence exemplifies this approach - born from contingent suffering yet transformed into apparent necessity through creative form. Similarly, the protagonist's tentative turn toward novel-writing suggests not escape from existential truth but its incorporation into creative activity. This fusion of unflinching awareness with creative affirmation offers a model for authenticity in a world without transcendent guarantees - showing how humans might create meaning while maintaining full awareness of their freedom and responsibility for the values they create. For readers willing to confront uncomfortable truths about human existence, this intellectual and emotional journey provides not comfort but clarity - not answers but a more authentic way of questioning.

Best Quote

“It's quite an undertaking to start loving somebody. You have to have energy, generosity, blindness. There is even a moment right at the start where you have to jump across an abyss: if you think about it you don't do it.” ― Jean-Paul Sartre, Nausea

Review Summary

Strengths: The review praises Sartre's beautiful writing and his incredible attention to detail in describing the physical world. It highlights the book as a work of genius for those interested in the art that emerges from darkness and the study of loneliness. Weaknesses: The review suggests that the book may not be suitable for readers who are emotionally unstable, jaded by love, or have struggled with desire, as it can be overwhelming and intense. Overall Sentiment: Mixed. The reviewer appreciates the literary quality and depth of the book but warns potential readers about its intense and potentially unsettling nature. Key Takeaway: "Nausea" by Sartre is a beautifully written, intense exploration of existential themes that may not be suitable for everyone, particularly those who are emotionally vulnerable. It is a work of genius for those who appreciate the art of darkness and loneliness, but it should be approached with caution.

Download PDF & EPUB

To save this Black List summary for later, download the free PDF and EPUB. You can print it out, or read offline at your convenience.